Carina Finn’s Poetry Youth

Some people, especially the eldery and more stuffy members of the Poetry Community, are disturbed by Carina Finn and her Poetry’s (LEMONWORLD & Other Poems)– brashness and bubbly-ness, “bratty”-ness. There’s an unwritten rule, for many, that success needs to be earned, not just by talent and the writing itself, but by paying your dues. (Gross!)

For these Ageists, these bigots, strong “bratty” writing is like Spring, cruel and raw, ruthless, and something to cry and bitch about. Blah, blah, blah.

But, anyways, following Joe Hall’s Poetry Road and Reb Livingston’s Poetry Home, this is the 3rd such photo shoot/interview where, again, the only rule was that Carina answer in language from her new book, LEMONDWORLD & Other Poems)

Besides Justin Bieber, Selena Gomez, Taylor Swift (is she really like Nazi art?), READ MORE >

Lyndsay Coloracci, EXPLAIN YOURSELF!

For the next episode of “Explain Yourself!” in which a writer is challenged to respond to my question about their piece before this post scrolls off the page, I’m putting Lindsay Coloracci under the light. Lyndsay lives in Philadelphia, and I read her poems in the beautiful new issue of Shabby Doll House.

For the next episode of “Explain Yourself!” in which a writer is challenged to respond to my question about their piece before this post scrolls off the page, I’m putting Lindsay Coloracci under the light. Lyndsay lives in Philadelphia, and I read her poems in the beautiful new issue of Shabby Doll House.

I find her direct address especially interesting—more interesting than usual—because the things she’s saying are more interesting than usual. I wonder what words she’s talking about, when talking about words that sound better articulated carefully. The line about kissing reminds me of Catullus. This line in particular gave me pause:

i am telling everyone that i just need one

non-painful experience and then that’s it

View more from “Explain Yourself!” here.

The First Three Books of The Malazan Book of the Fallen Series: A Primer and Review

The Malazan Book of the Fallen Series:

Gardens of the Moon (1999), Deadhouse Gates (2000), Memories of Ice (2001)

by Steven Erikson

One of the main hurdles epic fantasy has had to overcome has been making inroads with the literary crowds. However, in his piece “Easy Writers” for The New Yorker, Arthur Krystal observes that “the distinction between genre fiction and literary fiction has, of late, gotten less clear. Writers we once thought of as guilty pleasures are being granted literary status.” In a response to Krystal’s article, Lev Grossman wrote in a piece for Time that:

We expect literary revolutions to come from above, from the literary end of the spectrum — the difficult, the avant-garde, the high-end, the densely written. But I don’t think that’s what’s going on. Instead we’re getting a revolution from below, coming up from the supermarket aisles. Genre fiction is the technology that will disrupt the literary novel as we know it.

I think everyone can agree that good writing is good writing, irrespective of genre. Admittedly, for a while — particularly while I was in grad school — I’d been turning my nose up at sci-fi and fantasy (SF/F), ignoring the fact that the main reasons I wanted to become a writer in the first place were rooted in those two genres. Only upon closer inspection did I discover sub-genres, hidden within the minutia of those broad, overarching designations, particularly “epic-” or “high-fantasy” and “hard science fiction,” terms — similar to “surrealism” and “postmodernism” in that the practitioners of of each basically cringe at the labels — that showed me I was on the right track for discovering guilt-free SF/F reading that was also . . . dare I say it? . . . literary!

Gardens of the Moon opens with the armies of the Malazan Empire battling the free native city-states for dominance. It’s during an attempt by the Bridgeburners, one of the Malazans’ elite military units, to seize control of Darujhistan that we pick up the plotline. Epic events quickly begin to unfold from there.

Though it’s been mentioned around bookish corners of the Internet before, it certainly does bear repeating: do not expect much in the way of setup in Gardens of the Moon — Erikson sends you hurtling, face-first, into the Malazan universe where upon you land directly in the middle of the significant conflict I mentioned above. It can be a disorienting, even jarring experience. While the threat of an impending invasion by an oppressive empire seems like a bad thing, you still aren’t completely sure who to root for; you can’t definitively say who is “good” and who is “bad” (a distinction, like in Martin’s novels, that becomes increasingly more blurry as the series progresses); you are never totally sure of the stakes.

You just know shit is about to go down.

July 8th, 2013 / 11:00 am

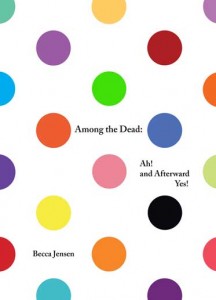

Among the Dead: Ah! and Afterward Yes!

Among the Dead: Ah! and Afterward Yes!

Among the Dead: Ah! and Afterward Yes!

by Becca Jensen

Les Figues Press, March 2013

75 pages / $15 Buy from Les Figues Press or SPD

Winner of the inaugural Les Figues Press NOS Book Prize as selected by guest judge Sarah Shun-lien Bynum

In Sarah Shun-lien Bynum’s forward for Among the Dead: Ah! and Afterward Yes!, she identifies the “atmosphere of allusion” that Jensen creates in the collection: “the feeling of reading great books: of being inside an enormous bell, a bell cast from the world’s wide store of epics and elegies and tales and novels, unable to tell where one’s own voice ends and the reverberations begin.” The ambition of such a project is belied by the small, and thus manageable and relatable, lens of an absurdist nuclear family: an unnamed daughter, a Collector, and the parents Mr. and Mrs. G. The family speaks and acts through fragments of English literary canon; they fish, sail, swim, and drown in the heartbreaking lines of Tennyson, Eliot (both T.S. and George), Keats, and others, but the ties of family make Jensen’s work more than collage poems. Because the characters are real within the world of Jensen’s collection, they have mysterious histories, present foibles, and future prospects.

The sophistication in Jensen’s assembly of Among the Dead: Ah! and Afterward Yes! can be seen as an advocacy for the acknowledgement of poetry as a product of linguistic innovation that cannot shed its ancestors. But what is important about the way Jensen looks back on everything that has created her work? The family in Among the Dead, though abstracted through a lack of traditional narrative, does not take place solely in a nostalgic chamber of fragments. There is a lived experience, an authenticity that can be vouched for despite its “fiction-ness.”

Mr. Grumble Grumbles

Like many heroes who find themselves haphazardly at the center of the plot,

Mr. G concluded that

a) this was a very stupid story

&

b) he didn’t care to hear it again.

“Mr. Grumble Grumbles” is a poem that appears very early in Jensen’s book, a piece that is un-prefaced by any of the Collector’s fragments until much later. Instead, readers are presented with an exhibit from George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss.

July 8th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Dear Rauan,… (2)

*****

[ this is the 2nd installment of my “Dear Rauan” advice column. special thanks, again, to Kim Gek Lin Short for reminding me that I can and should “help people” ]

*****

and, anyways, this time we have Marc from California

dear rauan,

i’m up for tenure–this is not the route I thought my life would take, and in the meantime every where I turn I hear a snide bro poet remark about lower than prestigious writing school teachers with shit for names and shit for publications. hmmm maybe I could give my shit name-brain to htmlgiant and mar their tar-stained code of duress. but I’m motivated to pursue higher than dick personality types READ MORE >

The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame

The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame

The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame

by Gengoroh Tagame, ed. Anne Ishii, Chip Kidd & Graham Kobleins

PictureBox Inc, April 2013

256 pages / $29.95 Buy from PictureBox

Passion is generally defined either as “any powerful or compelling emotion or feeling” or, within the context of personal relationships, as a “strong sexual desire; lust.” Strength & power are two words that dominate these definitions. Strength & power are two concepts that dominate the short, hypersexualized narratives of Gengoroh Tagame’s characters: strong, large & butch men dominating, fucking, & occasionally loving other strong, large & butch men.

In the world of manga, and especially in the imported consideration of such, there’s an abundance of yaoi stories that teen girls flock to, love, write fan-fic about: yaoi is a subgenre of manga that takes young, thin, often effeminate boys loving other young, thin, often effeminate boys. Clearly, there’s a contrast between this & what I’ve mentioned Tagame’s narratives hold above: thick muscles, thick cocks, heavy BDSM overtones–there is the occasional cross-generation ‘romance’ told by Tagame, but even the young boy shares a closer physic to a professional wrestler than the twinky waifs that populate yaoi.

Pierre Guyotat once remarked that he couldn’t write unless his cock was hard. Similarly, Tom of Finland once remarked that his best drawings occur while he’s erect. I have to imagine that the sexual narratives that overtake Tagame’s work drive their creator, as well, to sexual satisfaction. There’s a remarkable sense of erotic obsession that drives the work, moving from gang-bang fantasies to hyper-developed arenas of sadism. Sometimes, when there’s time for it to develop, a work develops a plot, often a somewhat complicated one considering the constraint of a number of pages. Sometimes there is less plot, but always there is a surge of powerful eroticism dominating each panel.

READ MORE >

July 5th, 2013 / 2:44 pm

A SMALL RESPECTFUL ARGUMENT WITH HELEN DEWITT, BUT WITHOUT HER

Last week when I emailed back an editor at a very fine, highbrow publication I responded to the way she closed her email by letting her know I actually have absolutely no intention of ever submitting my work to her again. She moved on to provide her apologies, which I guess should have placated me, but I kindly declined the apology, too. I forwarded the email exchange to a friend.

“You are crazy,” a friend responded.

I really like Helen DeWitt for many reasons, primarily because a friend, happening to be the very same one, once told me: “She is crazy. She gets in huge fights with her editors and doesn’t talk to them for years and wants her product to be exactly the way she envisions it.” If anything, I think that this is very not crazy at all; it makes the most complete sense to me that someone talented and verbally rigorous but never anything near verbose wants things the way she deems the most compelling. She edits herself more than enough, thank you very much.

There is a sentence somewhere [1] in DeWitt’s Lightning Rods asking: “Why does coffee never taste as good as it smells?” The question is a statement, and I do take it personally. Reading such a sentence fervently awakens my contrarian nature.[2] I have always liked coffee truly very much. As a child, I was undoubtedly the youngest one to bring coffee mugs to school, an action or habit eventually leading to phone calls to my parents from the school’s administration about how their son is a bad influence on other kids. Other kids wanted to drink coffee too. I was a trendsetter! How did the other kids know that it was coffee that the drink was in my silver traveller’s mug? It was the scent. The caffeinated aroma. The way its hot steam perpetrated the sterile educational environment. It smelled good.

A friend [3] once told me that there are only two ways to enter our bodies: sex and food. She then talked about abjection, but I kept thinking about our smells, smells and how smells too can be warm.

I have given it a lot of rational, logic-oriented thought and I have decided the reason I began drinking coffee was its warmth. It is possible that the average–or actually the median–reader assumed this would have been about the taste and how things are delicious and the flavor trip to Ethiopia and Costa Rica. But it is not, it is about warmth. The median reader–but definitely not the average reader, because the average does not think about things this much, if we are willing to be honest–wonders why coffee’s warmth is better than Nesquik’s. I would disagree, respectfully, with this median reader because there is a textural warmth to coffee that hot Nestle chocolate will never get near to at all. [4] In conclusion, I think coffee is always as good as it smells. Sometimes, my problem with coffee is that its warmth cannot be paralleled by its aromatic odor, or anything else at all.

Even if I disagree with Helen DeWitt on this tiny little section, I do think everyone should read Lightning Rods. The book is all about finding warmth, without at any point being warm itself. It is a book full of scents, but in the end I think we could all agree what is best is the possibility of warmth, even if it seems impossible.

NOTES

[1] The somewhere being page 71 if one needs be precise, read that page after reading 70 to achieve the optimal reader’s satisfaction.

[2] Recently, or at least not very long ago, I was questioned extensively and aggressively about this character flaw of mine. The largest issue I had with the accusation was the intrinsic flaw in denying it. My immediate paralysis in realizing that presenting a cajoling case was impossible was a relief. Internally I disagreed, but externalizing my disagreement was beyond the point, or actually it was the point, exactly.

[3] Still exactly the same friend in all cases. I guess we are close, or this piece would imply so.

[4] Not much later in my life my parents started receiving calls about how I was a bad influence on other kids: they, too, wanted to smoke. In my defense, I only did it because it kept me warm and made the coffee smell better, especially as its smell pertains to its warmth. My mom told the administration she has taught me well enough, thank you very much.

July 5th, 2013 / 11:16 am

Proving Nothing to Anyone

Proving Nothing to Anyone

Proving Nothing to Anyone

by Matt Cook

Publishing Genius Press, July 2013

86 pages / $13.95 Buy from Publishing Genius

Matt Cook’s newest collection of poetry opens with a telephone call: “The dry cleaner calls up and says he’s taking responsibility for my pants.” This line comes across as particularly mundane, even unpoetic, but starting a poem like you’d start a conversation has a long literary history. Back in 1959 Frank O’Hara wrote a whole manifesto about writing poetry this way. Of course, O’Hara was not entirely serious when he wrote “Personism: A Manifesto,” but the concept of directly placing the poem “Lucky Pierre style” between the poet and the reader has had a lasting impression on American poetics and Matt Cook’s Proving Nothing to Anyone reflects this pedigree.

Much like the poetry of Frank O’Hara, the poetry in Matt Cook’s Proving Nothing to Anyone has an air of artlessness to it, but this is a carefully calculated and constructed facade. Frank O’Hara’s work, especially poems like ”The Day Lady Died” are line after line of the banal, which abruptly shifts to the significant, creating a sense of the poetic sublime. The best of Cook’s poems are doing a similar thing. Take Cook’s “The Emotional Center” as an example. It starts off with the lines “Don’t mess with me right now, I’m all stirred up with emotion, man. / I’m in a rage right now because I can’t find my car keys” and continues to describe all the annoyances of life which are piling upon the speaker of the poem. The poem ends with this great description of anxiety:

And you’ve got all these emotional condiments,

And you take one bite and all this emotion oozes everywhere,

And you’ve got emotion running down your chin and your arm. …

Even though the words seem off the cuff, the perceptiveness of the lines really strikes the reader. The poetry in this collection reads as if Cook is on the other end of the telephone, or Gchat, or whatever popular means of communication is the equivalent of Frank O’Hara’s telephone analogy, and what Matt Cook has to say is really deep just as all 2 AM conversations have some element of deep importance beneath all the talk of bars and television.

July 5th, 2013 / 11:00 am

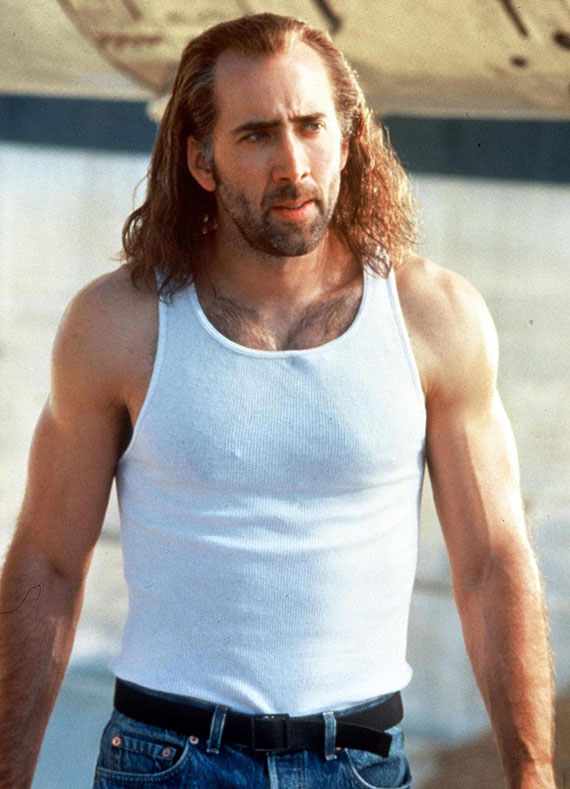

Paul Constant, at the Stranger, tells us why Nicolas Kim Coppola is a prophet!

read it, and more, at NIC TILL YOU’RE SICK

& if you’re in Seattle then go to Saturday’s one-day Cage Film festival called Nicolas Cage Match

(note: i’ve been a member of the Cult of Cage for quite a while already)

Interview with Taylor Davis-Van Atta, Editor-in-Chief of Music & Literature

I was recently introduced to the fantastic journal Music & Literature via their 2nd issue focusing on Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai and filmmaker Béla Tarr, both obsessions of mine. I was excited to have the opportunity to ask Editor-in-Chief Taylor Davis-Van Atta about the project.

I was recently introduced to the fantastic journal Music & Literature via their 2nd issue focusing on Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai and filmmaker Béla Tarr, both obsessions of mine. I was excited to have the opportunity to ask Editor-in-Chief Taylor Davis-Van Atta about the project.

(From their website:

Music & Literature is a 501(c)(3) charitable organization dedicated to publishing excellent new literature on and by under-represented artists from around the world. Each issue of Music & Literature assembles an international group of critics and writers in celebration of three featured artists whose work has yet to reach its deserved audience. Through in-depth essays, appreciations, interviews, and previously unpublished work by the featured artists, Music & Literature offers readers comprehensive coverage of each artist’s entire career while actively promoting their work to other editors and publishers around the world. Published as print editions (and soon to be offered as digital editions as well), issues of Music & Literature are designed to meet the immediate needs of modern readers while enduring and becoming permanent resources for future generations of readers, scholars, and artists.)

***

Janice Lee: Music & Literature is an exciting new project. Can you talk a bit about its inception and inspiration? I’m curious too about the very simple but semi-mysterious title? (For example, Issue 2 doesn’t seem to have very much music but a bit on film and photography.)

Taylor Davis-Van Atta: I sometimes think of Music & Literature as an act of frustration. It’s certainly a response to the longstanding shortage of high-quality arts coverage in English and, more recently, the austerity and cutting-back of coverage in our so-called traditional media. A lot of the arts review activity cut from newspapers has migrated online and proliferated there, and I often hear people say what a great thing this digital groundswell is, but I have to admit I find myself on the other side of this one… For the moment I’ll speak strictly about books and book coverage: while I can appreciate the benefits of a vast online book culture (broad coverage in terms of numbers of books, plenty of opportunity for young critics to strengthen their skills, etc.), the overall effect, it seems to me, is that a lot of attention may be drawn to the fact that a new book exists, but very little of quality and depth is actually written about the book. Add to this that discerning book and arts criticism has, for some time, been increasingly sequestered to the realm of academic journals—which are written and edited by academics, for academics—and I would argue that there is a missing class of accessible, smart, enjoyable critical literature available today to people who really love and wish to engage deeply with contemporary art.

All of this is just general talk, but maybe what I’m driving at (if anything) is this: if we agree that great art is inexhaustible, I think we need a class of literature that meaningfully engages that art, that offers new in-roads and allows us to explore the dark, recessed chambers of a book or symphony or film so we might see and experience it anew—or that simply provides the opportunity for us to discover an artist or piece of art we haven’t encountered before. This is the need we’re trying to address with Music & Literature. None of this is to say there aren’t venues—print and online—providing high-quality critical literature (I’ll not name names, since I’m bound to forget a few), but none that I’m aware of focus so intently as Music & Literature on providing art lovers with comprehensive, deep, and creative coverage of artists’ entire careers.

Since its inception, I have considered Music & Literature to be an arts magazine, broadly defined; that is to say, I’m interested in publishing all forms of art (and work about all forms of art)—and the more cross-pollination the better. While Issue 1 features two writers (Micheline Aharonian Marcom and Hubert Selby, Jr.) and a composer (Arvo Pärt), and Issue 2 features two giants of Hungarian art (writer László Krasznahorkai and filmmaker Béla Tarr) and a painter (Max Neumann), in each issue (and in future issues) readers will find, say, Noh theatre being discussed alongside the architectural nature of graphic scores, the musicality of an author’s prose discussed alongside the literary implications of a painting, and so forth. Though we chose not to feature a composer in Issue 2, the volume nonetheless contains quite a lot of musical material, including one of Krasznahorkai’s translators, George Szirtes, on the musical complexities of Krasznahorkai’s prose and the difficult pleasures of rendering them into English, as well as a discussion of opera and the nature of evil between Krasznahorkai and composer Péter Eötvös, and more… All forms of art are in constant dialogue with one another, and, for the individual, the experience of great art is the same regardless of the form that art takes: pleasure. For example, we marvel at the ingenuity of architects who reinvent space and encounter, but wither in buildings and structures that create anxiety. It doesn’t take much to intuit the parallels between uninspired architecture and uncreative music, for instance, because all art forms exercise our critical faculties. We enjoy it when our intellects are stretched and challenged: it’s the same part of us that revels in a great musical performance that is awakened by an architectural space that recognizes the human condition and works to incorporate and engage the individual.

As you know, I was first introduced to Music & Literature via Issue 2 (Krasznahorkai / Tarr / Neumann) when a friend of mine brought my attention to it. I was so excited to see both László Krasznahorkai and Béla Tarr as the focal points of a journal, as I’m working through these two figures in both my creative and critical work. What brought you to focus on these three figures for this issue? I’m especially curious since your website states your dedication to publishing work “on and by under-represented artists.” Do you feel these three are still “under-represented” as artists today?

As I suggest above, even the books that dominate chatter in the literary realm receive such little quality critical attention, much less resonate out into the broader culture. Despite some modest attention recently, I do think that Krasznahorkai and Tarr remain very much under-represented. Even if their names are recognized, their art remains largely obscured. This can be said, I believe, of all the artists we feature in Music & Literature. Micheline Aharonian Marcom, Max Neumann, Vladimír Godár, and Maya Homburger are known by very few, and their art resides in virtual anonymity.