Occurrences in Literature Right Now

Last nighttime, while trying to figure out if it’d be more appropriate to eat chocolate chip pancakes or cocoa pebbles for supper, my teddy bear Kmart sort of suddenly mentioned that there was a fair amount of occurrences in literature and perhaps I should tell of some of them.

Me: “Really?”

Kmart: “Uh-huh.”

Me: “K…”

On Sunday, Stephanie Berger will hold her first Poetry Brothel of the fall season. It’s at 102 Norfolk Street, starting at 8pm. The charming Irish boy editor of New Yorker Poetry, Paul Muldoon, will be there.

Yesterday, Carina Finn, for the first time in a rather long time, posted on her Tumblr, TH@SBRATTY. Her topic was the poetic life. “My life felt poetic only in the sense that hurt was the constant, and sadness, and want,” reveals Carina. “Not that I have been sad for forever, no one is, not even Hamlet, or Emily Dickinson.” Maybe so, but as long as they were on earth they were probably sad, as this place is filled with lunkheads who stare at screens 24/7/365.

Someone who is speaking about sadness as well is artist Bunny Rogers, who recently declared: “My depression is my commitment to drama. Viewing life as theatre creates a detachment that allows me to process an otherwise crushing environment of extremes.”

Though it is fall now, obviously, it used to be summer, and though summer is vulgar, this summer a relatable collection of poems and stories was published, meaning Gabby Bess’s Alone with Other People. This, too, is sad. One story is about a girl who “constructed herself as the modern tragic figure who would sacrifice herself for whatever.”

Unquestionably, the world is an utterly awful place, and it needs to go away fast.

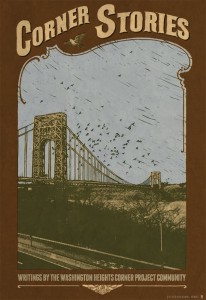

Corner Stories

Corner Stories

Corner Stories

by the Washington Heights Corner Project Community

Washington Heights Corner Project, July 2013

60 pages / $15 Buy from Washington Heights Corner Project

When I first started doing dope in my callow early twenties, I used to marvel at the raw story telling skill of the working class Vietnam veterans I bought bundles from, feeling like I had a God given duty to transcribe and capture their cant down wholesale in my journal. In the tradition of all those who slum, I felt like these men and their tales were my unique discovery. I’d absorbed the way the media uses drug users, the way they are placed in narratives as local color, punch line, or cautionary tale, and despite the fact that I was putatively joining their ranks, I wanted to pin these people to the page like so many trash talking, street wisdom dispensing specimens. I didn’t understand then that it was only in the first person that these voices had meaning.

The pieces in this collection, the literary magazine of the Becoming Writers workshop for participants of harm reduction organization the Washington Heights Corner Project, are indeed Corner Stories. As an injection drug user, I felt a great sense of comfort and familiarity reading these accounts, which sound so similar to the oral histories one hears passed down wherever drug users gather. It’s all here, from the lamentations about the difficulty of hustling, to the wily, wary disclaimers (“I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone”) and the paeans to the glory of the heroin of yesteryear (“a bag of dope back then was big…a lot of powder in one bag, enough to get two or three friends high,” Rubert Rey reminisces in “First Brush with Danger.”) Corner Stories also reminds me of the popular tradition of zines created by low-income rights and harm reduction organizations the nation over—Junkphood and the newsletters of Arise for Social Justice, for example. But Corner Stories is qualitatively a different project in the sense that finally, the oral history of drug users is being marketed and made accessible to the mainstream world.

Melissa Petro, editor of the lit mag and teacher of the workshop, writes in the introduction to the volume, “Maybe you have used drugs, or maybe you have never. Either way, there’s sorrow and pain in everyone’s life, just as there is joy. We all struggle to make purpose and meaning…” But most of the time, the struggles of drug users aren’t made known to the rest of the world, unless they’ve been watered down into the rote formulas of the recovery story or the special pleading of the confessional memoir. The simple folk wisdom of the subculture that I’ve heard while sitting around a circle fixing up, I’ve almost never seen written down, and certainly almost never for mass consumption.

September 27th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Interview: Sally Delehant & Emily Pettit

Named after former professional basketball player and humanitarian extraordinaire Dikembe Mutombo, Dikembe Press is a newish micro-press out of Portland, Oregon and Lincoln, Nebraska that publishes things, most recently Matthew Rohrer’s poetry chapbook A Ship Loaded With Sequins Has Gone Down and Emily Pettit’s poetry chapbook Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something. In celebration of the latter title, the poet Sally Delehant—author of the collection A Real Time of It (The Cultural Society, 2012)—recently conducted an interview with Emily P. to discuss Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something and Emily’s notions regarding anxiety, the definition of the word “conundrum,” dollhouse furniture and the artwork of Bianca Stone (which is featured throughout Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something).

Named after former professional basketball player and humanitarian extraordinaire Dikembe Mutombo, Dikembe Press is a newish micro-press out of Portland, Oregon and Lincoln, Nebraska that publishes things, most recently Matthew Rohrer’s poetry chapbook A Ship Loaded With Sequins Has Gone Down and Emily Pettit’s poetry chapbook Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something. In celebration of the latter title, the poet Sally Delehant—author of the collection A Real Time of It (The Cultural Society, 2012)—recently conducted an interview with Emily P. to discuss Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something and Emily’s notions regarding anxiety, the definition of the word “conundrum,” dollhouse furniture and the artwork of Bianca Stone (which is featured throughout Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something).

Word is bond.

***

Sally Delehant: The title of the chapbook begins with the word “because” which positions the reader to assume a “why” question floats in the background of the text. I’m wondering what you think that question might be? Does it have to do with why we curl up to a specific person or part of our world? Or is the title perhaps an answer to the big question hanging above all of us — “Why write a poem?” Someone smarter than I am said in a poetry workshop once that on a basic level a poem works out or goes deeper into some kind of anxiety. Something is either resolved or agitated more. Do you agree? Do these poems work like that?

Emily Pettit: I think there are a number of questions that lead to this “because” and two questions in particular. One is — why are we behaving this way? The other is — why are we feeling this way? Two rather general seeming questions, until they are connected to specific ideas and feelings encountered in the poems. The question — why write a poem? — is a question and is a question that I can see these poems pointing people towards thinking about.

Emily Pettit: I think there are a number of questions that lead to this “because” and two questions in particular. One is — why are we behaving this way? The other is — why are we feeling this way? Two rather general seeming questions, until they are connected to specific ideas and feelings encountered in the poems. The question — why write a poem? — is a question and is a question that I can see these poems pointing people towards thinking about.

In response to your mention of poems being ways that one might work through or with anxiety, I think poems are often working in this way, being asked to work in this way. In regards to my poems, I’m hesitant to use the word “anxiety” because I feel like I use that word all the time in conversations I have with other people and myself and that its meaning is not containing what I want it to communicate. Or various things the word “anxiety” communicates, I worry negate or dim the things in poems that I’m looking for as a reader and looking to make happen as a writer. A friend recently shared with me the following Borges line, “The metaphysicians of Talon are not looking for truth, nor even an approximation of it; they are after a kind of amazement.” In poems I am looking for amazement rather than truth or an approximation of truth. For me amazement might be experienced through encountering two words, the juxtaposition of which make music to my ear or a striking image to my eye. I am looking to be amazed by a feeling that arises when I encounter the ideas, images and music that I encounter in poems. Why I write poems is to find these things that I am also looking for as reader. Anxiety is everywhere, but something I love about poems is that a poem is a place where I do not need to name anxiety, should I not want to. Naming things can give things power or an agency of sorts and the effects of naming things can be good or bad depending on too many factors for me to list here. Poems are a place where I feel I have control over what my brain and heart give agency to. And to a certain extent I have control over the effects this agency has. I have not found many places outside of writing where I get to experience this sort of control. In the poems in this chapbook there are ideas about anxiety and ideas about ideas about anxiety, but they are existing alongside often adamant ideas that anxiety can be controlled and sometimes productively ignored and denied. What it is taking me a long time to say is, I like how my imagination deals with anxiety more than the way other parts of me deal with it.

Sally Delehant

SD: In the first poem in Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something you write, “I freak out, freak out, freak out, / with a quiet mouth,” and as I trace the freak out through the poem (and chapbook) there seems to be tension between doing/being what one naturally does/is and what one could/should do and be if that makes sense. You can wear a nametag that says Emily or rabbit and in another sense be the “best refrigerator ever” as well as many other things. What I’m clumsily getting around to on this sleepy, Sunday afternoon is that I think part of our humanity tells us we should should should be a certain way and we fear we might be “the most ridiculous person (we) know” as you write later. The most beautiful and comforting thing we can hear is that we are good dogs. The speaker “wants to be a good animal.” She wants to let us know that we “are exactly where we are supposed to be.”

Are there things that make you think you aren’t where you are supposed to be? Without being intrusive I want to ask you one thing that scares you, and then I promise we can talk about the beautiful drawings in the book which I am curious about too. What is a thing you are afraid of, Emily?

EP: I’m afraid me talking about fear outside of poems is like encountering a black hole. A hall of mirrors. My brain is exhausting in this way. I’m afraid that outside of my poems I fail to be funny about fear in the way that I want to be. I like that in poems I can feel funny about fear. I think anxiety and fear are absolutely linked. I have never encountered a definition of anxiety that does not use the word fear as a part of that definition. I like that when I’m dealing with fear in my poems, while writing poems, I do not feel anxious. Or if I am feeling something that could be defined as anxiety or fear, I’m not aware of it, or not naming it.

I think the thing that both my poems and my answer to your first question point to is a fear of both the presence and absence of control. It’s a conundrum. And I say conundrum, because I don’t think of a conundrum as hopeless. I like how in language with one word, conundrum, you can communicate a subject and a tone. For example, if you had asked me “What is a thing you are afraid of?” versus “What is a thing you are afraid of, Emily?”, to me the first question feels much less scary than the second question. Naming me has given me a louder agency, more loudly bonding me to whatever answer I answer. One word. A word. A name. For me to explore fear or ideas of fear in a poem is a place that I am not as afraid of exploration. Exploration feels not just possible but exciting. In conversation and in prose (like writing this now) I have trouble with this exploration; I feel accountable to ideas leading to resolutions of sorts, resolutions that very possibly do not exist. Resolutions of logic that are not expected in poems. Or are not expected by me in relationship to what I think of as a poem. I’m afraid of many things. I’m very appreciative of a poem being a place where I can have some control over my fears and how they feel to my brain and my heart and my body. I’m very appreciative for getting to write poems and read the poems of others for the ways in which this engagement allows me to escape my fears.

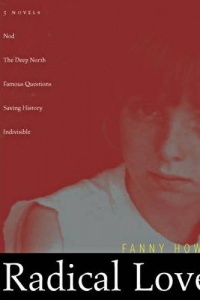

25 Points: Radical Love

Radical Love

Radical Love

by Fanny Howe

Nightboat Books, 2006

627 pages / $19.95 buy from Nightboat Books or Amazon

1. While reading Radical Love I was living close to the ocean and swimming every day. One afternoon I was feeling sad so I swam out farther than usual, surpassing all of my customary stopping-points, until I was so far out that I suddenly doubted if I’d be able to make it back. I recognized in what I was feeling the preliminary symptoms of panic; racing heart, flushed cheeks, repetitive thoughts about the panic I was feeling which only succeeded in increasing the panic. I floated on my back, trying to breath steadily. The stretch of beach I’d walked on only minutes earlier was now impossible to approach, a landscape which in its brazen totality had become not only remote but imaginary.

2. I realized that the ocean was terrifying because it was the opposite of lonely; it was abundant. By traveling so far from the shore I’d become an indistinguishable element of that abundance. The terror of my slow, lucid ego-death coupled with the necessity of moving my legs to keep myself alive was a stronger feeling than any kind of loneliness I’d ever experienced.

3. I arrived at Fanny Howe through an interview she did with Kim Jensen of Bomb Magazine.

4 . In the interview she describes her poetics as a reaching towards the ungraspable, the fragmentary, the bewildering. Her preoccupation is with the bentness of time. The freakish all-possible of moments, the vastness of living in simultaneity. How can two people be in two places at the same time? Or: How do we express actions occurring simultaneously?

5. There is a rare precision to her words. They scrape softly and insistently at a very particular feeling. In feeling it for the first time I realized it was a feeling I had always felt. A familiar estrangement. Like seeing a stranger in a dream for the second time.

6. The feeling is intimate with the abject. Between subject and object, the barely separate, like a limb cast-off or a corpse. It follows that many of the subjectivities in her novels are displaced and marginal; madwomen, children, monks. Kristeva writes that the abject inherently exists apart from the symbolic order of language, as a trauma irreconciliable with subjecthood. Fanny Howe makes a language for which abjection is immanent (a new subjectivity?)

7. A Sensual Metaphysics. There’s a body-depth to her narratives, a sense of being weighted, but not weighed down.

8. “She went to the caravan on her sister’s black bike through the dark and felt this way the happiness of being a hard sea animal that machines its way gracefully through the ecstatic interiors of the outside world.”

9. “She began to harden with the first baby. A firm heel slid across the palm of her hand, under her navel, now like a moonsnail with a cat’s eye at its apex. Her wastes, and the baby’s, moved in opposite directions from the nutrients. Her breasts tightened to tips of pain. She entered her psyche daily on rising…”

10. How do you write from inside madness? Most accounts of people going insane seem to come from after or outside psychosis, stressing the role of narrative as a stabilizing and ultimately redemptive exercise. In these texts there is more of a return to madness through narrative. No one is saved and everyone is ecstatic. READ MORE >

September 26th, 2013 / 2:37 pm

Greetings & apologies for the recent lack of content on my part (assuming anyone’s even missed me)—I’ve been wrapped up with writing a new book, and with teaching. But in a desperate attempt to stay current I’ll contribute the following vital question: uh, what’s your favorite color? Mine is blue.

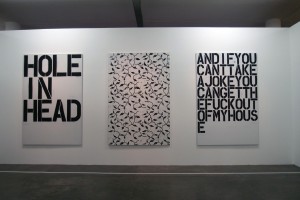

THE PERENNIAL AMBIGUITY OF CHRISTOPHER WOOL

I like Christopher Wool’s artwork. Wool became famous for his paintings of strong, provocative phrases in black letters, primarily ALL CAPS. Wool’s works are of an abstract nature, sometimes intricate in presenting an idea, other times arcanely elusive. In October’s Vogue Dodie Kazanjian scored a rare interview with the media-reclusive artist. The format and presentation of the arguments the writer provides to the text more closely resembles that of an essay, but many intriguing themes come up.

By introducing Willem de Kooning’s approach to artistic work–who worked “out of doubt”–as a starting point, the writer reveals the artistic intentions of Wool to be consistent in their omnipresent questioning and doubting. They are works defined by what Kazanjian calls a “perennial ambiguity.” This ambiguity may also be viewed as the proclamation of the honest confusion of an artist. Thus, the refusal of adopting an authoritative style should not be considered the result of limited intellectual rigor, but rather should be respected for its humility.

Discussing his artistic aspirations and how he managed to become a significant part of the modern art world, Wool asserts that his path was somewhat coincidental. “It just kind of happened,” he states. A key to his success was possibly that his early years in New York coincided with a legendary era of NY nightlife and culture: CBGB and Max’s Kansas City. The intersection of nightlife and the art-reality that was being created was evident in the 1980s, and shaped the public’s perception of artists’ role.

Upon revisiting his old work, the artist himself confesses: “They were offensive, funny, and indelible–you had to pay attention.” Consequently, it is not surprising that the critical response to his work varied. Some thought it populist in its negativity, while others observed in it a radical stance: a cacophonous harmony, or a refreshing pathos. What is predictable in his work is Wool’s lack of “conclusiveness” or the absence of artistic closure.

“I firmly believe it’s not the medium that’s important, it’s what you do with it,” the artist clarifies.

Someone Else is Sexist!

This will come around to David Gilmour if you give it a minute, I promise.

When Paula Deen was revealed as a terrible racist it was sort of funny at first. This rich older lady with her crazy over-styled silver hair and her pancake makeup and her cartoonish fantasy life wherein the height of class and luxury was paying black men to dress like dolls and dance for her gathered friends and family. She was such a perfect grotesque. But then the story wouldn’t die, and on the one hand I don’t like to judge anyone for a prurient interest in anything, but on the other hand I got pretty sick of seeing her face. And more to the point, I got sick of how much other people seemed to enjoy seeing her face. They loved to look at her and hate her.

I’m not saying she didn’t make it easy. She did.

But I think the root of the pleasure we took in Paula Deen’s fall was the pleasure of feeling superior to her. And I will grant you this: the odds are decent that you are not as bad a racist as she is. Probably your racism, like mine, is pervasive and ugly and embarrassing, but probably it is not garish. You have a little class about it. (So do I.) When you have a racist thought, you don’t immediately recognize it as such, but when you do recognize it, you have the good sense to feel really bad. (Me too.) So maybe, in this sense, you and I are better than Paula Deen — perhaps narrowly better, perhaps a lot. It’s hard to say. But what we probably aren’t is uncommonly good people.

I guess the thing is this: why was it so much fun to find out that this particular human being was a bit of a scumbag? Did you have a lot riding on Paula Deen before you found out she was a racist? I am willing to bet you did not. She only became valuable to you, if you are one of the majority who took such pleasure in her collapse, as I will freely admit I initially did, when she became a resource — when she became a fuel. We burned her and felt better for the smell her burning made.

But it’s not as if you didn’t know there were cartoonish, tacky racists out there, right? Please tell me that you knew. If Paula Deen was cause for joy, then you will have cause for joy until the day you are dead: there will be people like her so long as there are people like you and me.

The larger problem, though, is really you and me. Because we keep it quiet. Because no one has caught us yet. Because we’ll get away with it for the rest of our lives.

I have been working up to a question. The question is this: why is my Twitter feed, and why is the Internet in general, so excited to discover they are better people than David Gilmour? Furthermore, by what definition can they reasonably argue this is true? READ MORE >

……No More Sentence(s)……

***

The forthcoming, and 10th, issue of “Sentence: A Journal of Prose Poetics” will be the last. Yes, of course, just like people are born and die, journals come and go:

And yet— And yet—

Sentence is where I discovered poems and poets that changed the way I wrote: poems and poets (dead and alive, American and otherwise) that changed the way I thought about Poetry and its possibilities. Furthermore, Brian Clements, one of the founders and long-time editor of Sentence, was my first and best mentor when I began writing again (and for real) in Dallas in the late 1990’s.

***

So, to follow is a little Q & A that I just did with Brian which, among other things, looks back a bit over Sentence’s excellent 10 year run :

(note: back issues, except 1 and 2, are still available)

And yet— And yet—

***

Rauan: The Prose Poem seems to be in a much better place than it was when you started Sentence in 2003? I mean that now it seems Prose Poems are welcome and present just about anywhere. Is this part of the reason you’ve decided to stop?

Brian: I don’t know if the prose poem is in a better place; it’s in a different place READ MORE >

Stephanie Barber’s movie

Stephanie Barber’s movie