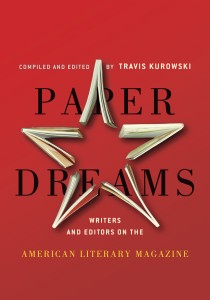

Paper Dreams: Writers and Editors on the American Literary Magazine

Paper Dreams: Writers and Editors on the American Literary Magazine

Paper Dreams: Writers and Editors on the American Literary Magazine

Edited by Travis Kurowski

Atticus Books, August 2013

432 pages / $29.95 Buy from Atticus Books or Amazon

In 1891, Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts set off one of the most dazzling and hilarious newspaper battles in the history of London theater. From just two private performances, the play garnered over 500 printed editorials, responses, and reviews, catapulting it into instant infamy and consequently playing a part in moving English theater a few steps closer to full-fledged theatrical modernism. Ibsen’s play is only one example of the inverse relationship between aesthetic influence and commercial success that seems to be part and parcel of much modernist art. The literary magazine is, of course, no exception. In Paper Dreams, a new anthology from Atticus Books, Eric Staley echoes this sentiment when he says that “the best the literary magazine can hope to achieve is influence out of proportion to circulation.”

Paper Dreams recounts over a century of literary magazine history in the United States through primary and secondary sources, ranging from editorial pronouncements by Ezra Pound (a nearly ubiquitous editorial presence early in the 20th century) to the savvy branding strategies of George Plimpton (The Paris Review’s luminous impresario) and beyond to the current renaissance of literary journals flourishing on the internet like PANK, Brevity, and The Rumpus. The aim of the anthology is, as editor Travis Kurowski puts it, to trace “the backbone and the outer rings of American literature.” Kurowski—a creative writing and publishing teacher at York College of Pennsylvania—began the project back in 2008 for The Mississippi Review and continued to research the topic because he wanted to, as he says in an interview, combat his ignorance on the subject. Paper Dreams certainly made me come face-to-face with my own.

Although there are so many wonderful pieces that deserve comment, my particular favorites are the ones that do some much-needed historical re-visioning. Jayne Marek’s “Making Their Ways: Women Editors of ‘Little’ Magazines” and Linda Lappin’s “Jane Heap and Her Circle” work to reclaim the editorial reputations of Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap of the Little Review. Marek states, “[I]t is clear that women had far more to do with the support and evolution of modernism than has been generally acknowledged.” And Abby Arthur Johnson’s article, “Forgotten Pages: Black Literary Magazines in the 1920s” reintroduces the reader to important black periodicals like the Saturday Evening Quill, Black Opals, Stylus (which produced Zora Neal Hurston), and Harlem and Fire (both which included Langston Hughes as a founding member).

In terms of the contemporary moment, the 2008 roundtable on the literary magazine was the most compelling. On the one hand, it revealed that not too much has changed in the last century. Editors still want to discover new talent, still hope to find that next great voice and all while dealing with perpetual money woes. They also continue to worry that there are too many journals and too few readers. As Algernon de Vivier Tassin said in 1916, “However barren were some departments of literature in the early days . . . magazines indicated at the outset their eternal disposition to multiply faster than the traffic will stand.” On the other hand, some things have indeed changed—the Internet, of course, being the most obvious. The distributive powers of the Internet are truly staggering; however, its ability to generate “noise” is equally awe-inspiring. Jill Allyn Rosser has the most interesting thing to say about the role of the literary magazine in our electronic age: “I don’t think that really happens anymore—the salon—and the magazine has become a replacement for that.” I am not sure if that is the case, but I want it to be true.

September 6th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Essay on things poets do when they decide to “sell-out,” e.g., how ridiculous their fall-back plans are. “Better just suck it up and write a bestselling novel.” “Translate poetry.” “Design board games.” “Invent a drink.” — #9 of 11 essays Zach Savich isn’t writing about contemporary poetry (over at the Philadelphia Review of Books)

Pynchon, Pynchon, Pynchon this fall. (btw this is a solid NYMag read by Boris Kachka: waddup doc)

Pynchon expressed vivid criticism of The Crying of Lot 49, which brings to mind the following larger question:

ARE WRITERS TRUSTWORTHY JUDGES OF THEIR OWN WORK?

White Privilege by Seth Abramson

(a poem of 400 true statements)

text version of the poem available at Ink Node here

This Empire podcast about The World’s End is worth a listen—the analysis is good, and the interview with Edgar Wright, Simon Pegg, and Nick Frost is illuminating.

While we’re on the subject, what are some of your favorite podcasts?

There are a few things I have been meaning to say and one of them is

Do you see the tree for the water? Sometimes I don’t, and then the dark melts up like a fat pit stretched out over the first note, the first noise. Silence. But it’s not the not that bruises. It’s the rim. It’s the interception that slays the calm that could have been. Whether it was or wasn’t both a lake and a fountain, it’s definitely that the feedback is too high. But is it water or sky you see? That’s when I sink into the couch and try to hide behind an open window, or a broken conk shell. The world is too bright sometimes, others not enough. You could say it’s exactly what it is, but it’s also a piece of wax. And we’re not killing it, because it is everything and everything else. We can, however, bruise it. We can pinch a nerve. We can not have home. I hope you’re still with me, because now I’d like to suggest some natural magic. Last night at my apartment a trill ripped the drone of my open window, forever unrolling one long quake like an ancient sometimes sea, the road. I went out to investigate, barefoot. I went down a hundred-year-old set of stairs dotted with dead leaves and trash. At first I saw nothing, just the road, which is not nothing so much as not what I hoped to find, which was a kind of softer terror. I heard no trill either, just the stream of cars, occasional garbage, probably leaves. I started back inside, up the stairs. I looked back once more to see a coon correctly use the crosswalk, trotting over from my side to the vacant lot across the road, a too-steep hill full to the brim with trees and shrubbery. The coon trilled and threw its head around. Rabies, I thought. Then I saw the tree, a pine I think, bend into the streetlamp. A swarm of raccoons, fifteen, maybe twenty, haunted the tree like a dark wind, almost motionless. Raccoons on top of raccoons. Raccoons where raccoons might not have been. I couldn’t see a bear, but I pictured a black-bear ghost chewing a mess of coons up there in a swirl of sparkling purple. A flurry of lower trills slackened as the raccoon cloud descended the staircase of leaves to the sidewalk. “Holy shit,” said a voice in the night. It was mine, but I didn’t know who it was for. No one was around. It was after midnight and Oakland is a heavy sleeper. Three of the coons crossed the street in different directions, looking back, avoiding all cars. One of them came my way and didn’t see me till it was close. I forgot that I was a little afraid. But I was bigger and I knew it. So did the coon. It crept in on a corner, behind some bushes, under some cars. It crossed the street in front of a honk, and shrank into the sewer like a huge rat. Then the tree was silent. Then the street was silent, for a while there were no cars. And that was the worst part, the silence. It starts at the rim. It’s what’s on when the internet is not. It’s not dinner conversation. It’s not a book. It’s not even a good way to say exactly what it is, which is why it’s better to say

September 5th, 2013 / 6:31 pm

25 Points: Creature

Creature

Creature

by Amina Cain

Dorothy, a publishing project, 2013

144 pages / $12.20 buy from Dorothy, a publishing project

1. I am ashamed of what I think about book reviews.

2. “I’m […] ashamed of what I think about literature—I can only open up to a few people in this way.” So says the narrator of “The Beak of a Bird,” the fourth short story in Amina Cain’s Creature (Dorothy, 2013). For now, I am hovering 40,000 feet above the Earth.

3. My thoughts about texts exist as emotional impressions, and what interests me most as a reader is ambience and affect—words as molecules of emotion, states of agitation, decorative illuminations, background noise. Readerly impressions in my bones are intimate like pages; they are, as in Creature, “the place where [my] life unfolds.” I want to recite my Creature to you, but instead draw inward toward the place where my body’s median axis, its midline, is askew.

4. Preoccupied with atmosphere and feeling as I am, I am ashamed of what I think (or don’t think) about literature, and so I choose not to write about books. But Amina Cain’s Creature is different: Amina Cain’s Creature resides out of harm’s way, although it exists in savage and erotic twilight. “I expressed myself through the violent putting away of a pan.” “Myself, alone, in my bed, is a story.” “Write about the arm when the whole body is being abused.” “We watch something violent on my laptop. It will help me wear this dress.” In this darkness, I read and write and think-along, and feel involved in every sentence. This involvement is key to my wanting to recite my Creature. Involved in it, I am pleased to feel ashamed of what I think.

5. Creature begs to be watched. Passing over one’s horizon of attention, the book is a meditative practice, which is not to say Creature is necessarily a meditation, for a person does not read Creature so much as she suspends it in space. 40,000 feet above the Earth, she observes its sentences, lines of thought that move across the mind, and breathes them in and out. There are momentary pauses of deep calm. It is likely the mind wanders. And as Creature unravels, the body sheds itself.

6. I am ashamed of my physiological responses to literature. See Exhibit A, which I am sorry to describe. In this disgraceful scene, I am hovering 40,000 feet above the Earth reading Creature’s “Attached to a Self.” I am attempting momentary pauses of deep calm. In the midst of this exercise, I cross a passage wherein Cain refers to a Benedictine monk: “The word is supposed to send a person into great silence,” she writes. “Just a little bit of reading is enough.” I suspend the statement in space, let it resonate. My eyes trace the sentence and tear.

7. Am I crying because of the story, someone asks, or because of the space?

8. Am I crying because of the space, I wonder, because this is the space where my life unfolds?

9. And is it really me if I’m not there?

10. To answer these questions for you, let me describe where Creature rests in my body—deep within my thoracic spine, in the middle of my vertebrae alongside photo booth-sized images of unrequited knives. I am conscious of it as I watch my body read. Its language moves and settles. This process of watching—as opposed to thinking—may seem enigmatic. It is. READ MORE >

September 5th, 2013 / 4:51 pm

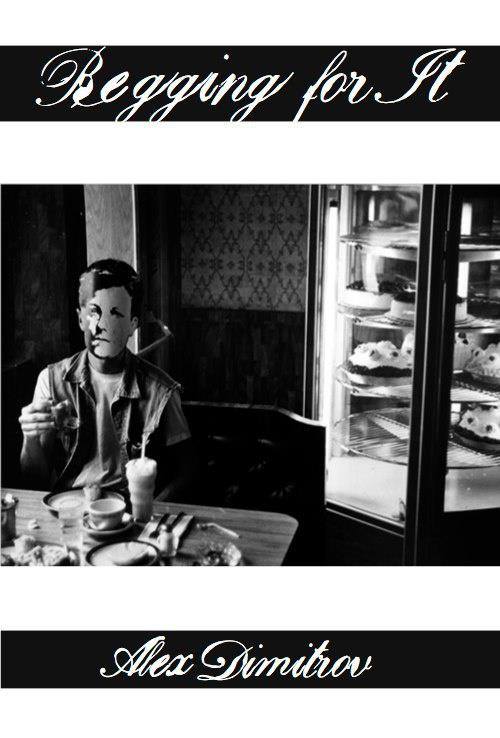

Alex Dimitrov: “It’s My Book”

***

The writer Ted Rees takes real issue with Alex Dimitrov’s decision to use a photograph from David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud in New York series as the cover of his book. Rees is clearly disturbed by this and over on his Tumblr (HARM MASSAGE) he fleshes out what he considers to be “a multitude of problems” in the form of a letter (DEAR ALEX DIMITROV) that you can read in full here .

***

Here, now though, is an extract from Rees’ letter:

…your use of Wojnarowicz’s photograph is, to quote a friend, “one of the most unconscionable appropriations” of another’s artwork that I’ve seen in years. It speaks to a self-importance wrapped in ignorance at best, and a type of colonialism at its worst. Through social and perhaps physical capital, you have acquired an image, totally denuded it of its creator’s political and social intentions, and made it into what you imagine is a reflection, and thereby a representation, of yourself and your work. The act debases Wojnarowicz, whose life was punctuated by poverty, hardship, confusion, and resistance, and whose work attempted to bring attention to how these elements worked on his own life as well as the lives of those around him.

***

***

And, to follow, now, is the transcript of a little Q & A that I did with Alex:

***

Rauan: You don’t seem too bothered by Rees’ criticisms. But could you tell us why you chose the Rimbaud Wojnarowicz piece for your cover?

Alex: Wojnarowicz’s work is important to me—the anger and passion READ MORE >

Championing Re Re’s, Condemning Democracy: the Baby Marie-Antoinettte Interview

Once on a day not too long ago (though not too recent either) I met up with Baby Marie-Antoinentte. The second Bambi Muse baby despot, Baby Marie-Antoinette acquired remarkable notoriety for her “Dear White Race” letter, published in the spring of this year. But, obviously, Baby Marie-Antoinette has monstrous more going for her than just internet fame. Soon, Baby Marie-Antoinette will be the queen of France. Her reign will coincide with the French Revolution, that disgraceful period when the Third Estate (know as “the middle class” in America) will degrade, divide, and, in some cases, behead Baby Marie-Antoinette’s adored family.

Our meeting place was a charming diner on the Upper East Side. In an old-fashioned red-and-white striped booth, I took sips of a Sprite while Baby Marie-Antoinette nibbled on a piece of positively sweet cherry pie.

Having turned down a tsunami of interview requests, I asked her politely if I could publish our chat as an interview. After pondering the possibility with her mommy, Empress Maria Theresa, Baby Marie-Antoinette agreed, as I am, after all, Bambi Muse‘s CEO (and, also, the Empress received final approval).

Me (M): Hi…

Baby Marie-Antoinette (BMA): Hullo…

M: Your cherry pie looks very sweet and yummy.

BMA: It is, just like Tinker Bell, Ariel, and Miley Cyrus.

M: Oh, a lot of people are saying mean things about all three of those girls.

BMA: Yeah, but America is governed by the 99 percent, and they’re average, so they hate specialness, whether it’s a special fairy, a special mermaid, or a special actress/singer.

M: There was tons of scorn slung at Miley’s VMA performance last Sunday.

BMA: Yeah, the 99 percent was very mean about that, but I wasn’t. Miley acted like a re re. And re re’s are magical, like bruises or something.

M: I have a bruise on my knee from getting tripped up on a sidewalk on Broad Street.

BMA: What were you doing on Broad Street?

M: Screaming curses at investment bankers.

BMA: Oy…

M: What is your perspective on capitalism?

BMA: I, too, champion inequality, exploitation, a class system, and so on. But none of those things should be based on money. Anyone can get that. The world should be based on something that’s not so darn indiscreet, like pretty dresses or poems.

M: Can you elaborate please?

BMA: Only chosen creatures can deck a pretty dress decorously, and, likewise, only chosen creatures can compose a captivating poem.

M: Who can compose a captivating poem?

BMA: Baby Ji Yoon can. And so can Baby Carina. They’re both re re’s. One of Baby Carina’s poems is titled CARIO, Y R U SO CRUELLL xXxX. As for Baby Ji Yoon, she says, “my bellybuttons are very impressionable.”

M: Uh-huh, they do sound like lovely and splendid special-ed girls.

BMA: There’s also this girl called Lauren Shufran. Many of her poems are metered. She also made up a word, “Turdecken,” a combination of turkey, duck, and chicken. Normal people don’t know how to count syllables or come up with their own vocabulary. They’re too laid back and communicative; for example, Cate Marvin.

M: The VIDA girl?

BMA: Ugh… VIDA.

M: Do you abhor that advocacy group?

BMA: You bet I do. What consequence is it if Ploughshares publishes 14.759837422222222 percent more boys than girls? They’re all average, interchangeable poets anyways. VIDA doesn’t care if a poem is illuminating; for them, it’s just accessibility and equality. And that’s not poetry, that’s Park Slope lesbian self-esteem talk. Actual poetry is very discriminative and strict. Sylvia is — she killed her daddy and her husband.

M: Tyrants are violent too.

BMA: Yeah, they’re decidedly diehard. It’s delightful. I hope that Syrian boy wins. Americans should stop bombing other countries and mind their own business. Nobody wants to be a democracy, it’s so gross, like pecking the cheeks of Lloyd Blankfein, Ben Bernanke, and Timmy Geithner one directly after another.

M: Yuck!

BMA: We should do something pretty now.

M: Maybe we could quietly sing that song.

BMA: That song?

M: Yeah.

BMA: K.

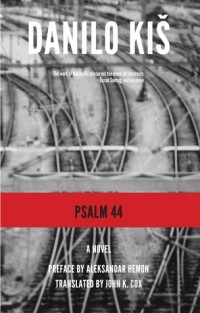

Psalm 44

Psalm 44

Psalm 44

by Danilo Kiš

Dalkey Archive Press, 2012

128 pages / $16.95 buy from Dalkey Archive Press

Rating: 9.0

“The work of Danilo Kiš preserves the honor of literature.”

-Susan Sontag

In his Psalm 44, Danilo Kiš offers something beautiful and immediately important. The novel, set in the Auschwitz concentration camp, confronts deep tragedy.

As a writer, Kiš trends expansive, with long lyrical passages:

“She remembered the return from the village, and her perplexity at not traveling by train (the way they had come) and only then by cart through the fields of rye and poppies, but they covered the whole distance back in a cart, moving continuously alongside the tracks with their thundering haughty trains, and she loved travel by train, as did her mother, who had told her she had loved to travel by train, but just now she said she preferred to lurch along the bumpy village lanes, where there isn’t any way to shield your head and so the sun strikes you directly on the pate, right on the crown of your skull. Then they reached the city and Marija said to her mother that she’d had more than enough of this cart and that she would at least like to ride the streetcar at this pint, to ride the blue one that went from the train station straight to the corner of their street where the chestnut blossoms were…”

September 3rd, 2013 / 6:57 pm