I Like Church A Lot

Hey, I had to go to a church recently. I was doing some childcare for a relative, and it was on a Sunday. Kids of a certain age lead an orderly life. Included in the order of the lives of the kids for whom I was providing some childcare was their regular Sunday morning visit to a Unitarian church in Seattle. Being a dutiful relative, I agreed to keep the child to the child’s orderly life and attend a Unitarian church service with the child.

And I had a pretty good time. It seems I like church a lot.

Turns out even though I stopped going to church 28 years ago, and even though I attended an Anglican church during the years I attended church, I still had all the rhythms of church hardwired in me. I may not have known the specifics of the creed or the words to the hymns and the prayers, but I felt like I knew all the gestures and the sentiments. I knew when to stand and when to sit. The Unitarian service’s language seemed a little strange to me—it was 19th century, and felt American, and seemed weirdly concerned with architecture—but everything else clicked into place pretty easily.

Best of all, though, it gave me an opportunity to sit and really think about death. I mostly don’t really write anymore. I mostly just sit and think about death. I mostly try to sleep and can’t sleep because I start to think about death and then find I can’t sleep because I’m thinking about death. And I mostly feel weird about lying in bed thinking about death because it doesn’t seem like the right place to be thinking about death, so I don’t sleep. I should be trying to sleep. I should be trying to clear my mind. I fight to clear my mind. I fight to clear out thoughts of death. And I fail and fail and fail.

Churches, as I’m sure you are already aware, are all about death! They don’t ask you to clear your mind of all thought of death.

And the church didn’t just give me a place to think quietly about death. It was a place to think about it actively and in a participatory way. It gave me plenty of cues telling me that I was in a place where thinking about death was encouraged. I found myself thinking about death in the proper setting. The right context. It was fantastic.

Like:

Many of the seats in the church have little plaques on them. The plaques say that the seats were “given” to the church in honor of someone. And that someone is dead!

Many of the books in the church have bookplates in them. And the bookplates say that the books were “given” to the church in honor of someone. And that someone is dead, too!

The programs they give you when you enter the nave to find a seat are filled with the names of the dead. The songs sung in a church are slow and quiet and mention death a lot. There are moments in a church service when everyone is asked to sit quietly, and during those moments, you can hear little creaking noises and breaths and coughs. Human bodies are filled with gas, and after death they make creaking and sighing noises. And the “death rattle” is a sort of choking cough people near death make when their throats fill up with saliva they can’t swallow because they are dying and all their energy is going to that instead of to swallowing.

And, of course, a church was just lousy with older people who are really close to their own deaths. They’re the ones making most of the noises in the moments of quiet reflection. Because their bodies are getting away from them. Because getting older is just the our bodies getting away from us. Until finally, we can’t stop our bodies from getting so far away from us, they cease to function entirely. Try as we might to stop it from happening, our bodies just give up. Think about that next time you are unable to keep from coughing. Your brain fights and fights, but you cough, because you can’t will your body to stop. You’re going to die someday, and it might be like that. Your mind might be sharp or it might be dulled with medication or decay, but it might still try to will your body to keep going, but your body won’t have you telling it what to do. It will just stop working.

Thinking about that in church felt far less menacing to me than it does when I’m in bed, and the person next to me is asleep. And I’m not asleep, but I’m trying to sleep, and instead I’m worrying about death.

I like church a lot.

Have a good weekend, everyone.

Does anyone know if the Pulitzer Prize is awarded to the author or to the book?

For example, in 1952, did Marianne Moore win the Pulitzer Prize for Collected Poems or did Marianne Moore’s Collected Poems win the Pulitzer Prize?

Is either acceptable?

A Handbook for the Perfect Adventurer by Pierre Mac Orlan

A Handbook for the Perfect Adventurer

A Handbook for the Perfect Adventurer

by Pierre Mac Orlan

Trans. by Napoleon Jeffries

Wakefield Press, October 2013

104 pages / $12.95 Buy from Wakefield Press or Amazon

It’s easy to be intimidated by a dude who has written upwards of 130 books, not counting flagellation erotica. But then you take a look at the sketch of him on A Handbook’s first page, labeled “Private First Class Pierre Mac Orlan, Military Cross,” and (if you are like me) immediately relax:

That’s the story of reading A Handbook for the Perfect Adventurer. Peppered with (actual, academic) footnotes, headed by chapter titles like “The Various Categories of Adventurers” and “On the Role of the Imagination,” you get the sense starting out that you’re delving into some serious study of the adventurer’s role in early 20th century French literature.

Part of this weird effect comes from what Wakefield Press does with the book. Design is stark, almost academic—but handbooky, too, with that authoritative streak the pocket-guide folks always mean to bestow. The 13-page introduction (and this is for just over 50 pages of content) has actual history in it, from a brief discourse on the French novel at that time to a contextualization of the book within the aftermath of World War I. Even the translator’s remarks on A Handbook’s inherent, decontextualized value is a sober meditation on its potential synecdochic value with relation to the history of adventure at large.

But once we get into the text, the book turns out to be pretty fucking hilarious. Mac Orlan keeps you on the rocks for a while, taking pains to distinguish the “active” from the “passive” adventurer, the cavorting blockhead from the armchair fiend of imagination. It’s still possible, in these early sections, that he’s entirely serious about the theoretical structure he’s setting out. Until we start getting stuff like the list that accompanies an account of the Active Adventurer’s troubling youth:

The Sad Setting Adopted by the Young Adventurer

The frog inflated by a simple straw.

Goldfish swimming at the surface with the help of corks pinned to their backs.

June bugs pulling a tiny scrap of newspaper through the air from their backside.

The fly without wings.

The ridiculed dog.

It goes on. Details like this end up being a serious redeeming factor of A Handbook for the Perfect Adventurer. There’s something about their oddball quality that tingles for having crossed the century in the way it has: slowly, as only three of Mac Orlan’s books had been translated into English before this one. It feels good that there were folks in 1920, too, who prioritized being funny and a pain in the ass, leaving more “serious” tomes to the hand-wringers.

Though with the tongue-in-cheek mode, as we know, a whole lot that is of interest can be conveyed anyway. There is certainly something being said about the dreamer here, when Mac Orlan outlines the strict “exercise” regimen the Passive Adventurer must undertake:

If one considers Passive Adventure as an art, some natural gifts have to be allowed for in future initiates. These gifts must be practiced and perfected. It is a question of intellectual gymnastics that include daily exercises and in particular the methodical training of the imagination.

The cool thing here is that he’s not affecting a take-down of anyone in particular. Sure, he’s giving a reasonable amount of hell to the person whose pulse begins to race at the words on a page that represent a steaming sea battle, or a life-altering meeting with the natives of a remote island. But this is more of a poke at the idea of adventure at large. (Ah, Napoleon…the introduction was right!)

While Napoleon Jeffries’ portion of the book remains fairly staid, aiding Mac Orlan’s straight face, even he occasionally jumps in on the fun in the text of a footnote. Eye the prioritizing of information in this one, one of many clarifications of Mac Orlan’s name dropping in the text:

26…Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877) was a politician, historian, and in Karl Marx’s words, a “monstrous gnome”; his best known work is the multivolume History of the French Revolution.

By the end of A Handbook, we’re digging it. Under the heading “Benefits an Adventurer Can Gain from Traveling,” Mac Orlan has included:

Seasickness.

The adventurer is exploited like a milch cow.

The adventurer is too hot.

Tortures pertaining to entomology.

Boredom.

Disgust.

The self-same chapter ends, totally inexplicably, with the single paragraph:

November 15th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Laura Kasishke’s House to House

House to House

House to House

by Laura Kasishke

Likewise Books, October 2013

32 pages / $8 Buy from Likewise

Laura Kasishke’s work rarely resembles itself. In her last full-length collection, 2011’s excellent Space in Chains, she oscillates from prose blocks to bone thin stanzas, from whispery pastorals to searing, phonetically prickly poems about domestic abuse. The book’s strength comes from the constant mood of anticipation it creates and then, poem by poem, evades.

Kasishke’s latest, House to House, is a chapbook of just forty pages – not much room for the schizoid self-differentiation of Space in Chains – but, as the title suggests, Kasishke still achieves an impressive amount of movement from cover to cover. The book spends most of its time in the realm of memory – in almost every poem the word remember crops up or, very loudly, does not – but as the collection progresses, Kasishke departs from the typical nostalgia of reminiscence to a stranger ambition: she seeks to remember as an act of creation, to use memories not to solidify her identity but to unharness it and allow it to wander landscapes of memory in whatever form she chooses.

In the first poem of the book, “Daysleep,” Kasishke uses her own memory of “sleep, in May, in the afternoon, like / a girl’s bright feet slipped into dark new boots,” as an entryway into the collective realm of sleepy memories. Sleep becomes the link between the poet and a “smiling child hiding behind / the heavy curtain of a photo booth,” “brides in violets,” and “sleepy pilots casting / the shadows of their silver jets / onto the silver sailboats / [sailing] / on oceans miles below.” Here, she sets her consciousness free to alight on each of these “personages,” casting about their mundane but evocative experiences. The poetics of memory become the poetics of deterritorialization, pulling Kasishke out of herself instead of further inside.

But this project of self-emancipation through memory is rarely so successful. Throughout the collection certain images appear in poem after poem and act as barriers that interrupt the disembodied flow of Kasishke’s identity. These images are of doctors, hospitals, angry fathers, or absent gods and they appear in the poems like malevolent ghosts. In the poem, “House to House,” Kasishke demonstrates her failure to use her memories however she wants:

moving from porch to porch in

jilted swarms. Remember? Every

summer night as the lights went out?

How they made their rounds

in tattered hospital gowns?

The moths, at first a metaphor for poetry’s ability to move freely from porch to porch as demonstrated in “Daysleep,” become “jilted” and transform, in the last lines, to nurses in “tattered hospital gowns.” This bleak, spooky image resonates with pain and resists the type of free association necessary to escape the identity-forming tendencies of memory.

The further Kasishke goes into memories the more she runs up against these types of images, hiding in the dark corners, poised to remind her of something awful. The poems become charged with the tension of an erratic psyche struggling to escape some terrifying baggage, and Kasishke’s unpredictable and often disturbing imagery communicates that terror well. Suspense in poetry is rare, but the startling turns in House to House from images like a “girl’s feet slipped into dark new boots” to a “gull snatching the diamond necklace from the drowning girl’s neck” demonstrate the dangers of reckless remembering in way that transmits the experience instead of simply describing it. While the specifics of Kasishke’s memories stay buried, they darken the atmosphere of almost every poem in the book and, like a ghost moving through a house, exasperate and terrify by refusing to step out into the light.

***

Parker Smith is a writer of fiction and poetry living in Salt Lake City, Utah. His poetry has been published in the likewise folio and in Inscape. He has fiction forthcoming from Bodega. He currently teaches elementary school in a town near where he lives.

November 15th, 2013 / 11:00 am

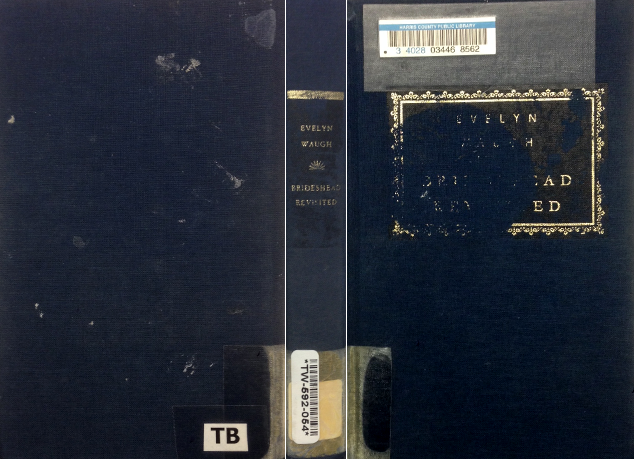

Brideshead Revisited

I’ve always loved Random House’s Everyman’s Library, cloth bound hardbacks with cream colored pages, gold leaf case stamping, decorative endpapers, a red silk ribbon bookmark, learned introductions, and extensive chronological tables for each author’s life. In this fashion, I’ve taken Leo Tolstoy, Vladimir Nabokov, Somerset Maugham, Thomas Mann, among other great men, to bed with me. A man whose life is missing a plot does well reading them. Where literal illustrations are devastating to the imaginations Walden, Moby Dick, and perhaps even Alice in Wonderland deserve; where Chip Kiddian flashy design turns a book into a poster; and where shiny paperbacks — from the glossy trash at Walmart, to flimsy new releases granted every fresh MFA — have somewhat anticipated the disembodied medium of Kindle, Everyman’s Library’s austerity marks a forgotten past. Could this be mere obsolescent snobbery? Please. And so, you can imagine my dismay at the people of Harris County in Houston, Texas, for doing what they did to my dear Evelyn Waugh (who is a man by the way, lest you think I became a feminist). Here is a troubling thought: that the most sensitive and educated demographic of Harris County may have ejaculated on my book. Also, inside it smelled like dog. Don’t mess with Texas.

November 14th, 2013 / 11:53 pm

Is there a reason the use of the word “literally” has become such a bothersome issue for all of us? What made it possible? Who is to blame?

We need a resolution.

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail: Stories

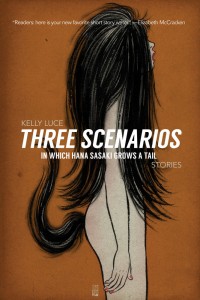

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail: Stories

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail: Stories

by Kelly Luce

A Strange Object, 2013

152 pages / $14.95 buy from A Strange Object

1. Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail is the debut story collection by Kelly Luce.

2. It fits on a bookshelf of modern Japanese writing somewhere between Yoko Ogawa’s Revenge and Banana Yoshimoto, maybe even one shelf up from Haruki Murakami.

3. The only thing is that Kelly Luce grew up in Brookfield, Illinois.

4. How strict is the “write what you know” edict? On Big Think, Nathan Englander reminds us that this advice is too often misconstrued. It really means we should write from a place of emotional familiarity, not that we’re limited to autobiographical writing.

5. But are there limitations when we talk about writers depicting foreign cultures? This story collection seems very Japanese (if a book can even be “very Japanese”) and yet, it’s distinctly American, too.

6. When I was nine I was flipping through channels and caught the end of Akira on basic cable. I had no clue what was going on, but in the weeks, months, and years to follow I found that it left an indelible mark on me—a predilection towards the uncomfortably strange.

7. A Strange Object is the name of the independent press that published Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail. They’re based out of Austin, TX. This is their first book, too.

8. This is strictly conjecture, but Japanese culture affords for a strangeness that is uniquely its own. Look at all of the Japanese fiction out there: Akutagawa and Mishima, Ryu Murakami and Haruki Murakami, and the scores of manga and J-horror.

9. The characters in Kelly Luce’s collection are outsiders. Many are Americans who move to Japan for work or to connect with the culture that they find so entrancing. Some are only half Asian, an anomaly to the native Japanese—not gaijin, but not Japanese, either. Others are fully Japanese, but do not fit in as with the Japanese school girls who seek refuge from the tedium of their lives through a unique karaoke machine and with the Japanese widower who invented a machine that measures a person’s capacity for love. All are lost. All are searching to fit in.

10. In ninth grade, I ordered a t-shirt with the kanji for gaijin on it. I wore that shirt proudly even though no one at my school in West Tennessee understood what it meant. Looking back, I think I was so drawn to Japanese comic books and cartoons because it was a way to embrace my otherness as a nerdy, awkward white boy. READ MORE >

November 14th, 2013 / 11:14 am

– – watch this imagining it’s Janey Smith!!

– – watch this imagining it’s Johannes Göransson!!

– – watch this imagining it’s Alt Lit in toto!!

(just kidding… just kidding)

Speaking Through

Late 2013

This tribute to anti-office poet-burnout Slash Lovering–who died on this day in 2004–continues indefinitely.