David Fishkind

David Fishkind was born in Worcester, MA in 1990. In 2008 he spent ten days in Nova Scotia. He lives and works in New York.

David Fishkind was born in Worcester, MA in 1990. In 2008 he spent ten days in Nova Scotia. He lives and works in New York.

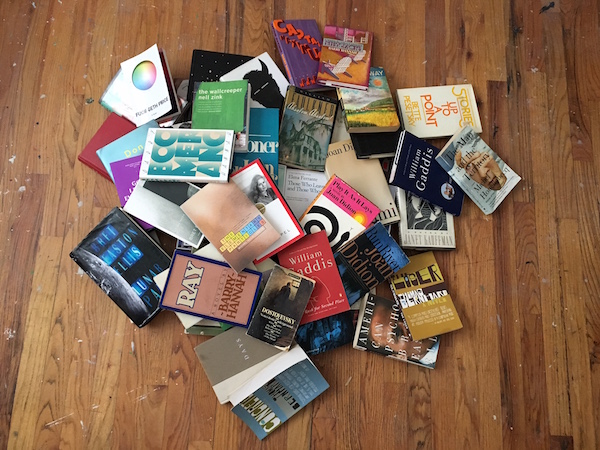

What follows is a list of all the books I read in 2020.

(What follows that is a series of statistics regarding this list, and some other things.)

*Previously read

READ MORE >

Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner. (Jan. 19-26)

A lot of things were happening, and I thought I was in love, maybe, ultimately, wrongly, but I was distracted. And I was devastated, and I decided to challenge myself with a difficult read. I hadn’t been reading much by the end of 2015. Bad things were happening. The light in my room was affected by a red lampshade from a previous tenant, and I lived in Bushwick, and I often raced to get through my allotted daily seventy or so pages so I could go to sleep. I wasn’t talking to anyone, and I had no one to talk to about the book. The book is about history and the removal of the experience from the event. I felt like I missed a decent amount, that there seriously lacked the emotion of Faulkner’s other great works, but I enjoyed the places and the desperate, pre-suicidal voice of Quentin, who felt like an old friend, from a time when I had been more excited about literature and life. I was happy when the novel was over.

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov (late Dec. 2015-Jan. 31)

I started this book sometime in December (but it was not the first book I read in 2016), and found it pedantic and boring. But after finishing Absalom!, driven (not in a car, but figuratively) to my parents’ house, I felt I had no excuse but to push through it. I hate letting a so-called classic defeat me, or get past me, and I hope to one day lay that feeling to rest. If people like this book so much it must be for a reason; there are some nice sentences, but people probably just like it because it’s like a movie, and I read it by the fire, while my parents watched TV. I read the majority in two sittings that way. Sometime earlier, however, a woman approached me, at my cashiering job at the food coop, and told me I was disgusting for reading Lolita in public. I told her I wasn’t.

The Tennis Handsome by Barry Hannah (Feb. 1-2)

I had fallen into some weird freelance things after quitting my salaried, union-benefitted, university library position the previous summer. I had reason to join the public library and was ripping video of a fashion label to media cards, testing that they worked and mailing them out all over the world at a highly inflated rate. It was nice to make money off so little work, but the work soon went away, and I had to find more. Hannah’s fourth novel is an amalgam and extension of several stories from his hit collection Airships, and is mostly about sex, like a lot of his early work. It was a pleasant read for the most part, even making me laugh, and then I was in Massachusetts. I didn’t have a car and was out of touch with most of my old friends. I didn’t have much reason to go back to Brooklyn.

An analytical approach to living, that is a problem. I said it to S, I said I didn’t think that the examined life was the right one. I said it was, well, I could look it up it was on Gmail, but I’d rather try to remember. The point was, I was trying to tell him. I didn’t try that hard. I knew he wouldn’t like it if I put it that way, but the point was what I was feeling, which was that the too examined life lacked the types of brief, transcendent emotions that made it meaningful. If everything was studied very precisely, tried to be understood, attempted to be made into language, something was lost. More thoughts seemed to occur without language. Its usefulness to one’s, like, being could be put in question.

He seemed to think I was an idiot, he might have said so. G said what could I expect, he made his whole life based on that kind of tenet. That way of looking at things—S is a PhD—and trying to put that into some comprehensive explanation. Also he’s a poet. He never talked to me again. I can’t remember if I tried to strike up conversation with him. It must have been in winter. Could it have been during the time I was still doing crosswords? that was obviously a conflict of interest for me. There was a thing where I would always see the same words coming up, which was distracting. They’d be too easy or too hard.

I can find very little middle ground in stuff like that. I don’t know if I’d had the thought, but what if, what if, I had told him that I was more concerned with the exact reality as it appeared from an empirical, outside perspective, and that inner thoughts deflected it… Would it have been a lie? that actually bothers me a lot. How when you pose a question in writing (not a question in terms of “idea” but in terms of, like, a person thinking a question, I often think one vies to answer it), I always want to answer it immediately.

It was sort of a great relief, one less force to fear incurring—is it incurring?—my madness. My ideology appears, like it had sprung, only through disagreements with people. It’s weak. I felt like I’d escaped from the possibility of living S’s life. Something that required so much attention to the things beyond itself might cease to be substantive. Things are more often than not, I assert, concerned with what is directly, immediately happening.

The Bus ran monthly in Heavy Metal from 1978 to 1985.

Imgur has hosted as a bunch of strips. Below are two.

The Bus rules.

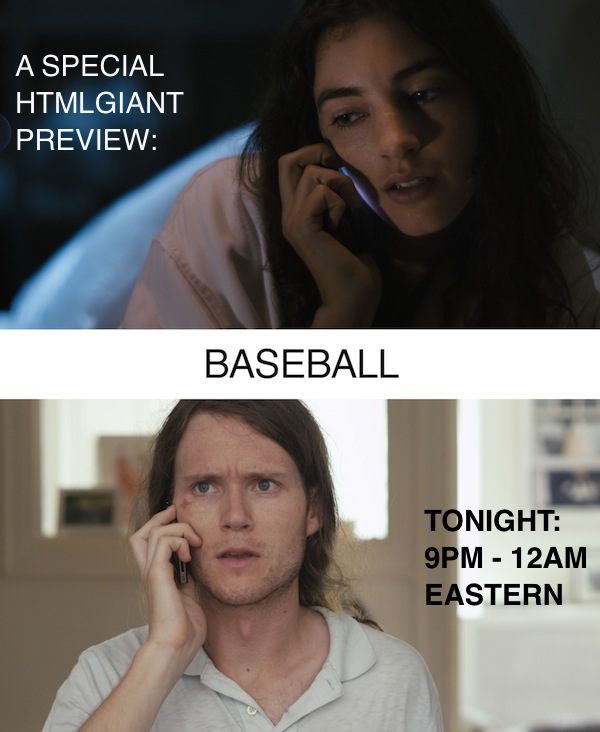

Adam Humphreys and Zachary German have produced a short film called Baseball, which was available to stream right here on HTMLGiant for 3 hours Aug. 7, 2013.

Zachary German, who co-wrote the film, stars as a cheating lover who must recall the opening of The Great Gatsby from memory to placate his suspicious girlfriend.

The link below is now dead, contact Adam Humphreys (adamphump@gmail.com) for more information.

Baseball is America’s pastime. Everybody loves baseball. This film has nothing to do with Baseball. They’re playing with you.

Two apartments and one hotel room. A young couple in different time zones. A young guy (Brad) drinking a bottle of Fiji water. A phone call comes through. It is from his girlfriend. A brief exchange establishes they live together. He’s lying to her. She asks him if she left a book on the side table, “The Great Gatsby,” which results in a genuine and convincing look of concern on the part of Brad. It goes from there.

Everything you see and hear in this film is important. The background is important. A cat is important. Brad’s pompousness, in their interaction with another couple, when he quotes from The Great Gatsby in flashback, is important. In very few scenes, the film manages to flesh out the characters pretty well. These are real, believable people in a somewhat wrenching but not unfunny scenario.

I feel a similar cosmic humor in Humphreys’ other two films. And a similar uncanny and profound feeling of disconnection as in German’s earlier literary efforts. Little details, like the cat, the cat’s water, and the couple’s conversations lead inexorably to a muted emotional breakdown. The opening passage of The Great Gatsby, quoted by Brad three times in the film, proves meaningful on multiple levels.

The first time through, it’s funny. The second time it’s not so much. Pain is a big part of comedy. Baseball is a tight little film that will reward multiple viewings.

Simeon Stylites, who spent thirty-six year on top of a sixty-foot pillar in the Syrian desert. For most of that time his body a mass of maggot-infested sores.

The maggots no more than eating what God had intended for them, he said.

– David Markson, Reader’s Block

– – –

And her eagerness to learn the preparations he had set himself to teach her was sometimes pathetically touching, and sometimes it frightened him: touching, delicately absurd for there was no mockery in her when, for instance, she affirmed the dogma of the Assumption of the Virgin with that of Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, as the only historical parallel she knew; frightening, when she brought from nowhere the image of Saint Simeon Stylites standing a year on one foot and addressing the worms which an assistant replaced in his putrefying flesh, —Eat what God has given you . . .

– William Gaddis, The Recognitions

– – –

These considerations, which occur to me frequently, prompt an admiration in me for a kind of person that by nature I abhor. I mean the mystics and ascetics—the recluses of all Tibets, the Simeon Stylites of all columns. These men, albeit by absurd means, do indeed try to escape the animal law. These men, although they act madly, do indeed reject the law of life by which others wallow in the sun and for death without thinking about it. They really seek, even if on top of a column; they yearn, even if in an unlit cell; they long for what they don’t know, even if in the suffering and martyrdom they’re condemned to.

Music by Kanye West. Commentary by Lakshmi Singh, Leonard Lopate. Beer by Pabst Brewing Company.

Instead of attending an opening for a collective of internet/new media artists in Red Hook, probably cutting edge, funny, with free alcohol—perhaps some level of thought-provoking, also maybe I would’ve known some people there—I decided to go see Francis Ha. Something said it was like Baumbach meets Girls, and since Lena Dunham and the aforementioned filmmaker (whose notoriety is mainly based on a 2005 family drama and his friendship with the more marketable and visually stylistic Wes Anderson) both, in the shallow arc of their careers, mark an acme of New York indie-cum-commercial, I figured I’d get more pleasure and cultural experience out of going to the movies. I’ve always been attracted to the medium’s commercial roots: the amount of money it takes for a 90-minute feature to be made: the amount of money it costs to finance advertising: the amount it costs to see it once in theaters. Counteracted against the mutable possibilities for distribution and audience now made possible by the internet. It’s a weird time to consider one’s self an artist making movies, probably. Weirder than posting photos of a MacBook in a bathtub to a Tumblr.

Even weirder to film your movie in black and white. A bold choice, it actually succeeds, raw and captivating rather than kitschy and meaningless. Baumbach creates a Manhattan-like air to parts of the city heretofore unexplored in traditional analogue (i.e., Brooklyn). Its passé, but really more pastiche, approach to the cinematography feels enhanced by the literal quality of the film print. I don’t really know how that works, but certain moments feel faster, like World War II footage or old home movies. Frances (Greta Gerwig) runs down the crosswalks of lower Manhattan to “Modern Love” dancing and sort of fluttering. It’s not dramatic; it’s comic and natural and sort of frantic.

And that’s how the majority of the film is. People in their mid-20s banter and talk around ideas (and the dialogue is good, not parodic, not pandering or striving to capture some extant zenith of hipster inflection). Everyone wants to be an artist, but nobody really cares or knows how. Frances, an aspiring modern dancer and graduate of Vassar, traverses six shared, and unsuitable, residences, not including a 48-hour stint at a friend of an acquaintance’s apartment in Paris, over the course of maybe eighteen months. She fails at relationships, she sulks and hopes and talks like an intelligent person who doesn’t care about being intelligent. Someone at a dinner party says something like, “Sophie—she’s really smart,” to which Frances replies something like, “Well, yeah, we’re all smart.” She claims her friend doesn’t read enough, but we only see the protagonist flipping through the center of some thick book, ostensibly Proust, on one of her countless wasted days.

Frances is wildly unmotivated and expects a natural progression of success in the art world from minimal, obligatory efforts. She has basal talent, illusory goals and lots of beer. And she gets drunk a lot, fractiously speaking down paths of unrelatable and undetectable revelation amongst people either too mature for her company or just as immature and wanton, but rich. Frances isn’t rich. By economic and social terms, she is absolutely poor, but addressing the harrowing nature and implications of this situation becomes increasingly difficult, as she admits, when confronted by her vague love interest and roommate, that she cannot be poor, essentially because she is educated, art-minded and white. The story really does seem beautiful. It is more honest and intense than Girls, more willing to quietly face the complications of inheriting a broken economy, a feeling and system of entitlement, privilege and unwarranted desire. Nothing could really be more current, topical, desperately vital to address.

Oh god, I’m so sad. Frances Ha comes so close.

Yesterday I went to the Brooklyn Museum to see the exhibition “Workt by Hand”: Hidden Labor and Historical Quilts.

Quilts are awesome.