Unteaching in the Creative Writing Classroom

We do a lot of teaching in writing classrooms, but we also do a lot of unteaching. This is particularly true in introductory creative writing classes, where a large percentage of our work is undoing what teachers before us (in elementary and high school) have done.

I want to be clear that I’m not picking on English teachers here. Both of my parents and many of my friends are English teachers and I have the utmost respect for them. They do great work exploring the history and meaning of literature in their classrooms. Typically, though, they are not themselves devoted to the craft of imaginative writing. They’re literature scholars who are asked (sometimes against their will) to do a unit or two on creative writing as part of their curricula. Wisely, teachers in such situations often use the “Creative Writing Unit” as an opportunity to hone students’ skills in spelling, grammar, punctuation, vocabulary, and other fine points of the language. While they may be better off in terms of vocabulary and punctuation skills, there are often negative consequences for their creative compositions.

Below are some examples of these unintended consequences. These are bad habits I’ve seen young writers bring into my classroom and how I’ve tried to help them break free.

READ MORE >

The Best Version of Whoever That Is: A Teaching Philosophy

Ed: Over the coming weeks (and maybe months given the number of posts I’ve received), I’ll be featuring conversations about the teaching of creative writing from teachers, both new and experienced, as well as students, all of whom are trying to answer the question, “How the hell do we teach creative writing?” Our first post comes from Laura van den Berg, author of What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us. –RG

—

For a handful of years I have been teaching creative writing in a variety of settings, mostly academic. I entered into the whole enterprise feeling a touch uneasy about claiming to be able to teach that maybe can’t be taught. My biggest worry was oversimplifying. I knew my students would need to learn the craft fundamentals of fiction, but how could I convey them in a way that does justice to the form that I love, the form that thrills and confounds me on a daily basis? Fast forward a few years and I have some ideas. I always tell my students there are no rules in fiction, only principles. Here are some of my teaching principles:

1. One of the basic problems in introductory-level workshops is that students are grappling with how to talk about what they and their peers put on the page. At the same time students want to come to class with something to say, preferably something smart-sounding (and often they succeed; I am regularly knocked-out by how insightful my students are). This can result in an unhealthy attachment to surface level issues, such as the dreaded questions of plausibility—i.e. “Was it really plausible for Aunt Ida to walk 10 miles in a hurricane? Shouldn’t it have been more like 5?” Unfortunately these questions have little relevance to the larger enterprise of the story. Of course Aunt Ida could have walked 10 miles in a hurricane and if for some reason she could not, that issue can be addressed with a margin note and a click of the keyboard. What the student probably means to say is something like: I don’t believe in the world you’ve created. You’re not convincing me. And questions of world-building are way more fruitful conversation topics than how far someone can walk in a hurricane. I ask that students push themselves—both in their reading and in discussion—beyond the surface, toward those underlying questions. I have gone as far as to ban the word “plausibility” (“likability” is another one) from workshop, as it is so often a euphemism for: “I sense there’s something going on here but I don’t have the language for it, so I’m saying this other thing instead.” Let’s help our students find the language.

Art’s a Fucking Mess

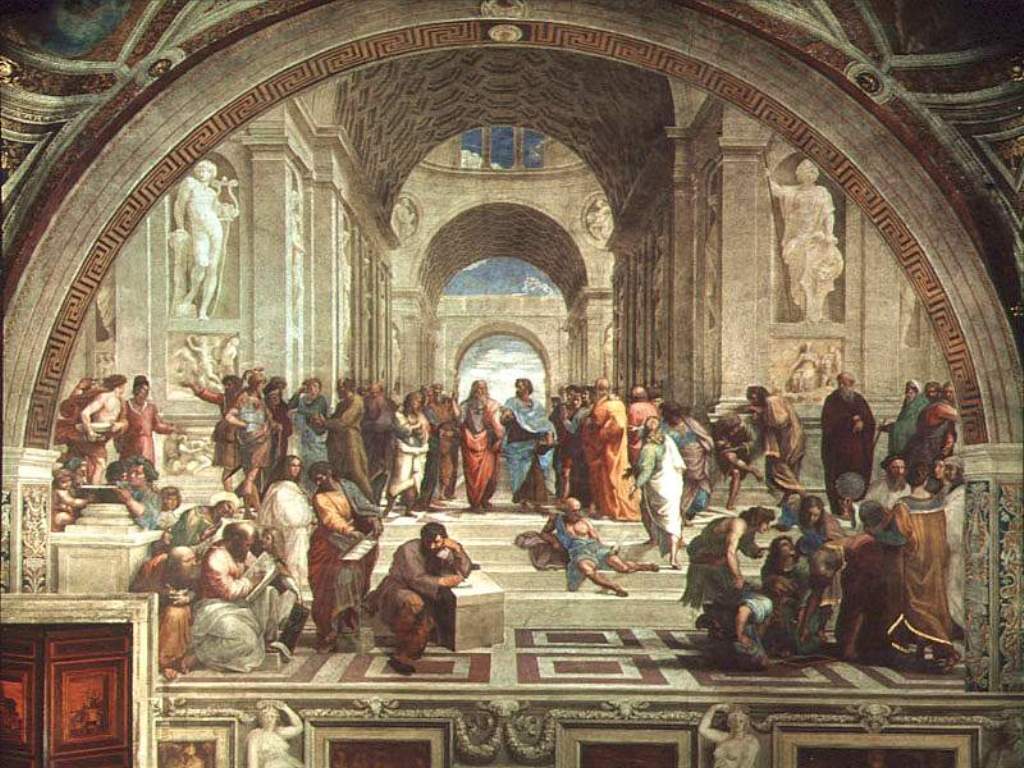

My friend Tadd over at Big Other has a post up about why Plato wanted to kick all the poets out of his ideal republic. And I’m no philosopher. But my understanding has long been that Plato’s problem with poets/art (besides the whole mimesis “copy of a copy” thing) is that art is messy, uncontrollable.

Like, consider this:

Someone—some artist somewhere—decided to make this. Is it good? Bad? Funny? Sick? Evil? Juvenile? Calculated? Hip? Clever? Stupid? Immoral? Amoral? Sure—it’s all those things, and more! It supports a variety of readings. In fact, the better an artwork is (I think this is a pretty OK one), the more irreducible it tends to be (at least, according to certain lines of aesthetic reasoning that I think Tadd would agree with).

Good art disrupts the social order. It wakes you up, shocks you, makes you feel alive—it makes you see the world again, differently. Bad art is boring, predictable, prescribed, a weak illustration of what you’ve already been thinking. (That’s my problem with so many depictions of September 11th, Roxanne—they reduce that day into something so digestible, so mundane, it’s as though it never happened.)

“My mis-shapen head cracks through all the clichés.” – Jules Renard, on Writing

Years before Twitter and Robert Walser, Renard maximized the miniature. These are all from The Journal of Jules Renard, which Tin House reprinted in 2008, written between 1887 & 1910.

“You can recover from the writing malady only by falling mortally ill and dying.”

Boris Spassky on Writing

“I also follow chess on the Internet, where Kasparov’s site is very interesting.”

“I don’t want ever to be champion again.”

“Computer defends well, but for humans it is harder to defend than attack, particularly with the modern time control.”

“Time control directly influences the quality of play.”

“I lost to Bobby [Fischer] before the match because he was already stronger than I. He won normally.”

“We were like bishops of opposite color.”

“The power of hanging pawns is based precisely in their mobility, in their ability to create acute situations instantly.”

“The shortcoming of hanging pawns is that they present a convenient target for attack. As the exchange of men proceeds, their potential strength lessens and during the endgame they turn out, as a rule, to be weak.”

“Nowadays the dynamic element is more important in chess – players more often sacrifice material to obtain dynamic compensation.”

“If they had played 150 games at full strength, they would be in a lunatic asylum by now.” – (on Kasparov and Karpov, 1987)

“The place of chess in the society is closely related to the attitude of young people towards our game.”

“When I am in form, my style is a little bit stubborn, almost brutal. Sometimes I feel a great spirit of fight which drives me on.”

“The best indicator of a chess player’s form is his ability to sense the climax of the game.”

“I don’t play in tournaments, but I follow some.”

How The Hell Do We Teach Creative Writing?

I taught a fiction workshop over the summer, I’m currently teaching an introductory fiction class this semester and next semester I will be teaching a graduate workshop. Teaching fiction has been fantastic and by far the most professionally satisfying experience I’ve ever had. I normally teach professional and technical communication so recently I’ve been consumed by the question, “How the hell do we teach creative writing?” It’s so hard to know how to do all of this right.

A great many writers succeed without having ever taken a writing class and there are intangibles that cannot be taught but I am still interested in what we can do where creative writing pedagogy is concerned. How do we best reach and help students in the creative writing classroom? How do we teach students about the elements of creative writing and then how do we teach them to experiment with these elements? I want to assemble a series of guest posts on this subject so I am opening the discussion here because many of us are either teachers or students of creative writing or once were students of creative writing. Anything is possible. I would love to see reflections on what works, what doesn’t work, great classroom experiences or those that were not so great, how to teach creative writing and the introductory, intermediate, advanced, and graduate levels, reading lists with explanations why those texts are being used, instruction on the professional aspects of being a writer, teaching different forms, poetics, and more.

If you’d be interested in writing a guest post, from either the teacher or student perspective, about some aspect of creative writing pedagogy, please get in touch (roxane at htmlgiant.com) so we can talk more.

Magic The Gathering as Literature, part 3: The Vocabulary

Players react as Josh Utter-Leyton defeats Sam Black in the semifinals.

It’s day three of Pro Tour Philadelphia, and the final (“Top 8”) competition is underway. This part of the tournament is webcast (you can watch it live here), and is also being transcribed. (Since this is such high level play, players will want to read descriptions of what, precisely, happened on each turn; this is what Bill Stark was doing in the photo at the top of Part 2.)

These match transcriptions often read like a foreign language to non-players. For example, here’s an excerpt from a write-up of a match played yesterday between Jeremy Neeman and Luis Scott-Vargas:

Magic The Gathering as Literature, part 2: The Articles

Bill Stark (seated far right) documents a feature match between David Williams (seated left) and Brian Kibler (seated right).

Greetings once again from Pro Tour Philadelphia! The second day of the tournament is well underway. As you’ll recall from Part 1, I’m curious to what extent this event—and all Magic culture—is a literary phenomenon. The most obvious place to start seems to be the wealth of Magic articles produced every day by the game’s players, designers and developers, judges, and casual bystanders, some of which I think will interest the upstanding gormandizers at HTMLGIANT. Let’s take a closer look, shall we?

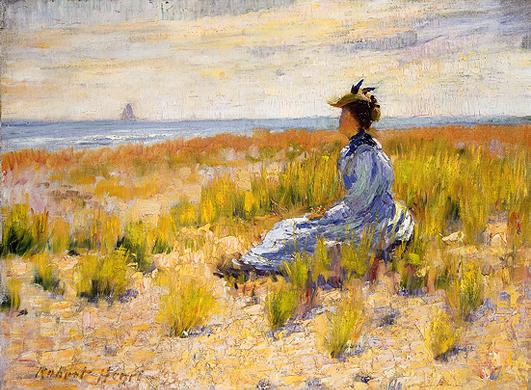

Robert Henri on Writing

“The picture that looks as if it were done without effort may have been a perfect battlefield in its making.”