On Fandom and Aliens Remaking the World

I am interested in the concept of fandom. Do you have a “fan” kind of relationship with the things you love? I feel like I have a very fan kind of relationship with the things I like, even if the people who make them are “nobodies” to society. I am a fan of random people, people who make beautiful things, people that have what I call the 6th sense—which is a special kind of perception, a special way of seeing or knowing. For example, Bhanu Kapil. I have a list of suspected “aliens”—passionate people that possess certain qualities. Bhanu is on it. Eileen Myles is on it too—I could listen to her talk all day because it’s always like wandering through a very fascinating and specific brain. I guess I don’t understand casual people—people that get enough sleep, people that are regular (as in consistent), people that find it easy to make new friends….

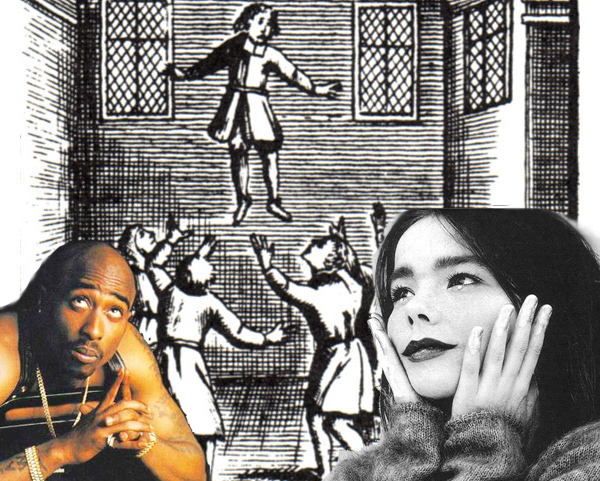

The epic poem that I wrote recently was about trying to find the lost aliens of planet earth, crisscrossing the country on foot in search of the other alien beings. Actually, most of the poem is about obsessively trying to escape through a crack in the sky until I am told by Tupac, who lives in the kingdom in the sky, that I should not try to ascend but should focus on my world—on “this worldliness.” That’s when I start trying to find the lost ones. I chose Tupac because my brothers and I were such big fans as children, and still to this day I think of him as a dynamic figure—tough and sensitive with radical and intellectual tendencies. So Tupac tells me I’ve got it all wrong. He encourages me to redirect my vision. I listened. I stumble upon a mysterious post office in Wyoming that has rows and rows of open postal boxes and I leave letters in the mailboxes knowing that the lost aliens of planet earth are the ones who will reply. We find each other and sing a note real loud and blast all of the beings that are ready to make the new world into the sky. As I am ascending Bjork is below me wearing a big dress while looking at me with tears in her eyes because she is so moved (I was a very big fan of Bjork growing up). One by one, we cross over into a crack that opens in the sky.

9 commas, still wearable, happy turnip day

11. Yo, sonny, there is a new Diagram out.

10. The Business Insider offers 33 unusual tips to being a better writer. They seem obvious, stupid, sometimes smart, rarely unusual. OK, this was unusual:

Take a huge bowel movement every day. And you won’t see that on any other list on how to be a better writer. If your body doesn’t flow then your brain won’t flow. Eat more fruit if you have to.

8. The Decemberists ripped off all of Dr. Dre’s The Chronic.

On Memoir and Experiment: The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch

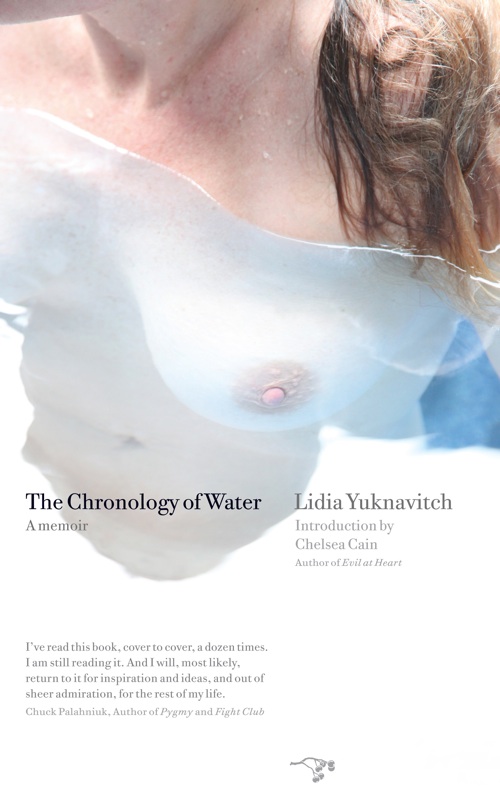

I’ve spent the two days reading and re-reading Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water. After years of avoiding memoirs and thinking they were not for me, the past several months, I’ve been reading all kinds of memoirs and learning about the many different approaches to the genre. I might have to admit I really love memoirs. I don’t know if it’s because I’m very curious about the lives of others or if I am drawn to the confessional in nonfiction as much as I am in fiction but right now memoirs are speaking to me pretty seriously.

I’ve spent the two days reading and re-reading Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water. After years of avoiding memoirs and thinking they were not for me, the past several months, I’ve been reading all kinds of memoirs and learning about the many different approaches to the genre. I might have to admit I really love memoirs. I don’t know if it’s because I’m very curious about the lives of others or if I am drawn to the confessional in nonfiction as much as I am in fiction but right now memoirs are speaking to me pretty seriously.

I first heard about the book because I saw the cover here and last week I read this awesome essay on The Rumpus, by the author, about the cover and the heresy of a woman’s bared breast, nipple and all, on that cover. Then I heard about the book from a friend so I ordered it and the book arrived and I read it almost immediately and then I read it again and one more time for good measure.

The book itself is a fine, heavy object both literally and figuratively. The cover is gorgeous and when you read the book you’ll realize how appropriate it is to the writing. But even more than that, the paper is thick and slick and the design is clean and the cover has a nice matte coating. I enjoy these small details that contribute to a sensual, in the very sense of the word, reading experience.

In my previous posts about memoir, I’ve discussed how I find it difficult to review memoirs because it feels like you’re doing more than critiquing the writing, you’re also critiquing the life lived. This isn’t a review as much as it is me talking about a book that is really powerful and unlike any memoir I’ve yet read. I’m also interested in how this book can be used for teaching because it challenges the traditional memoir in really interesting ways and because, selfishly, one of the graduate students I’m serving on a committee for is writing a memoir as his thesis and these notes will help me in my work with him. As I’ve thought through this book, I’ve considered the various elements that really mark a shift from what I traditionally see in memoir writing: how the narrative deals with the body, how the memoir can be read as an open text through the use of absence, language invention, an alinear narrative structure, and decadent but controlled descriptions of emotion. Of course I’m going to end with emotion.

March 3rd, 2011 / 3:30 pm

Concept Flash

The Concept Flash is not about an emotion (that would be expressionism, aka Kafka), but rather something larger, an idea.

The idea is then set, into concrete.

The logic of the idea follows the dialectic of the concept. This can assist you, in a structural sense, or even with the setting, characterization, narrative, etc. The attributes of the concept can be appropriated for technique within the flash. The concept flash is infinite in its manner. You could write a lifetime of these: ideas in our lives represented as things. Stop digging holes with your fingers. I am offering a type of shovel. OK, a spoon.

Will you shut up and provide an example?

Yes, I will provide an example.

Cube by Amelia Gray.

2 Teach or not 2 Teach

What authors are the most accessible to being taught, especially to young writing students (as in taking their first classes, not age)? What authors are not?

Example. T.C. Boyle. Very teachable. Consistently uses structures easy to graph/visualize, massive layers of basic CW language techniques, always some intent at theme. Now you can argue the merits of his fiction, but that isn’t my point. My point is the merits of the fiction as pedagogically useful.

(You could take this one story and teach a semester of Intro CW: Freytag’s, quest narrative, suspense, immediacy, imaginative prose, precise verbs, unreliable narrator, suspense, POV, etc.)

Diane Williams. Not so great to teach. The voice, the thought, the paroxysms of perfect, and perfectly odd, sentences—you could smother a young writer, you could lead them to a cliff’s edge and accidentally push them off. (Yes, I know Miss Flannery O’Connor, this would do the world a favor, etc.)

Now I generalize, I generalize, so don’t go all sack of hammers. And I’m not saying don’t read any and every writer (OK, not Jewel). And, with upper level classes, I think the ratio switches—Personally, I start bringing in writers I wouldn’t teach earlier (like Diane Williams, Barry Hannah, Gertrude Stein, etc.) and I start removing T.C. Boyle. And I’m not saying you need to take any writing classes, ever—this question is couched in context. OK, enough with the disclaimers. WTF?

I just wonder if you have your own choices: A writer perfect for the teaching of creative writing to young writers, a writer you might want to avoid? I’m sure many of you have had experiences, as student or instructor. What authors glowed, what thunked?

Who or what is your daddy.

Generally my least/most favorite part of any interview with any artist, and interviews with writers in particular, is when s/he’s asked “who are your influences.” It’s my most favorite because I’m a sucker for superlatives, all those kinds of “favorite book/food/animal” type inquiries. But it’s my least favorite because the answer is often a let-down, or something bordering a cliche, or someone so far-flung that I find myself questioning the subject’s veracity. Which I don’t really want to do. I mean, it’s an interview, not an interrogation, and I’m no arbiter of anything, as much as I might want to think I am.

In any case, I think there are interviewees who probably feel pressured by that question–they want to sound smart, and interesting, and relevant:

“Well, lately I’ve been reading a lot of Derrida with Yo Gabba Gabba on mute, and the overlaps are pretty incredible…”

“Obviously I owe a debt to Pynchon, and to a certain extent, Dostoevsky. But I’d be dishonest if I didn’t credit Bazooka Joe in some way…”

“Oh, I’ve been in an all-consuming back-of-cereal-boxes phase. General Mills, mostly. And I’m re-reading Proust’s A la Recherche for the fourth or fifth time.”

You get it. That mix of high and low, theory and novel, pop and baroque, that says I’m an intellectual, I’m legit, I’ve read things, but I also know how to breakdance.

I’m thinking about how DFW watched a lot of television as a kid.

I’m wondering what we mean, exactly, and Eliot/Bloom notwithstanding, by influence. Beyond the page, beyond the book, beyond all art, what informs your work, that you are conscious of? Do you ever try working against those forces? What’s your objective correlative, and how does it function? Like the bay leaf in the pot that flavors everything vaguely but needs to be removed before eating? You could eat it, but it wouldn’t taste very good? But maybe it needs to be eaten and it needs to not taste good, so that it can be evacuated?

Can We Not Talk About What We’re Working On Again, Please?

The pendulum has swung, as pendulums are so woefully apt to do. When I was small, and first starting reading about what writers said about writing, they all seemed to say that it was better not to discuss a work in progress. At the time, this seemed a kind of magic trick, a superstition of some kind. But I’d be damned if I didn’t take their word for gospel, even though I didn’t understand it any better than I understood the actual Gospels (I heard “Jesus is everywhere” and imagined a thousand teeny tiny invisible Bethlehem babies lounging around even as I bathed).

The pendulum has swung, as pendulums are so woefully apt to do. When I was small, and first starting reading about what writers said about writing, they all seemed to say that it was better not to discuss a work in progress. At the time, this seemed a kind of magic trick, a superstition of some kind. But I’d be damned if I didn’t take their word for gospel, even though I didn’t understand it any better than I understood the actual Gospels (I heard “Jesus is everywhere” and imagined a thousand teeny tiny invisible Bethlehem babies lounging around even as I bathed).

Apparently, I was damned. By the time I started writing in earnest, the whole mechanism had to do with not only discussing but sharing your work in progress. In college, this was great, because I wasn’t in any way ready to complete anything to the point that it could be published. So participating in workshops was like army boot camp. I learned lots.

In MFA school, I still learned, especially in literature seminars, but I certainly didn’t complete anything publishable. But this time, I was probably ready to, but was hampered by the workshop process. There were three reasons for this, I think. 1, in no workshop that I took did anyone say that a piece should just be abandoned. All criticism was constructive, which was the point, but in reality some work needs to be torn down so that something better can be built in its place. I’m very impressionable, so after hearing my work discussed for 20 or so minutes, I became convinced it was worth my continued attention even if it really wasn’t. But I ran into trouble with the continued attention because 2, my classmates’ and professor’s opinions about any one piece, even a 3-pager, were so conflicted, and the problems they unearthed so convoluted, that I was totally lost when faced with revision. To make matters worse, 3, my professors and classmates (not to mention lots of other people in my life–they all agreed) also told me what book they thought I should write, and how I should go about it. Almost five years later, I have only just really decided that they were wrong, and that the book they had in mind is not the one I should write, at least not right now. Like I said, I’m very impressionable. I have confidence in my own work, sure, but there is something powerful about everyone you know saying they want to read the same as-yet-unwritten book by you. Powerful and dangerous.

Get Me Up Close To the Lives of Others

Anytime an essay’s title riffs on a variation of “The Problem With [insert perceived source of a problem],” there is likely to be a problem. It is a provocative way to begin a conversation, surely, and provocation is often useful to instigate discussion but when there’s “a problem” with something, vague generalizations are likely to follow. In the Sunday Book Review this week, Neil Genzlinger wrote an essay, “The Problem With Memoirs,” where he takes issue with this “age of oversharing.” He writes, “There was a time when you had to earn the right to draft a memoir, by accomplishing something noteworthy or having an extremely unusual experience or being such a brilliant writer that you could turn relatively ordinary occurrences into a snapshot of a broader historical moment,” as if there should be a vetting process for who is or is not eligible to write a memoir.

For a long time, I was fairly skeptical of memoirs and did not necessarily see the utility in reading an accounting of someone else’s memories, particularly when those memories seemed to come from an ordinary life or a life not yet fully lived, as is the case for young memoirists. I understand Genzlinger’s frustration but his lament felt a bit narrow and shortsighted. When a very young person writes a memoir, I often wonder what they could have possibly learned, but that attitude is not necessarily fair, particularly because people often mistake memoirs for autobiographies and they are not the same thing. As I understand them, autobiographies recount the entirety of a life lived. Memoir, which takes its meaning from the Latin memoria, to reminisce, is about a moment or series of moments in time that might speak to something greater. Memoirs are more intimate in scope. A memoir tells a close story so it is not surprising then that memoirs are written by people of all ages, whether they have accomplished something noteworthy (a relative concept) or had an unusual experience (also relative), or not.