A Conversation with Deb Olin Unferth

Deb Olin Unferth is the author of Minor Robberies, a collection of stories, and Vacation, a novel, both published by McSweeney’s. Her new memoir, Revolution: The Year I Fell in Love and Went to Join the War, has been excerpted in Harper’s and The Believer. It will be published tomorrow in hardcover by Henry Holt.

MINOR: You left college in 1987 to join the Sandinista Revolution. You’ve written plenty between then and now, but not this story. Why did it take so long to decide that this was a subject for a book, and then to write and publish the book?

UNFERTH: I was very self-conscious about writing a memoir. For many years I wasn’t sure if it was a form with enough intellectual energy, which I now know was silly, since I’m very excited about memoirs and feel like they have tremendous intellectual energy. It was probably just an excuse for me. Also, I think maybe the story wasn’t over yet? Maybe I had to live a little more to figure out what the story was. Also I think I’ve struggled as a writer to figure out how to open up and reveal myself. Writing my novel, Vacation, helped me figure out how to do that, and afterwards I was ready to jump into the memoir. People had been telling me to write up my “revolution story” as a memoir for years. Tao Lin mentioned it to me I don’t know how many times. Also Nate Martin.

MINOR: What was the thing you figured out that allowed you to open up and reveal yourself more than you had in the earlier stories?

UNFERTH: I started out as a philosophy major. And I’ve always had an interest in form and in more intellectual styles of fiction writing. I think I was afraid to write with bald emotion, I thought it was too feminine or something. I think the breakthrough came when I read Chris Ware. I read that big red book of his, the compilation of Acme Novelty Library. It was very formal and right from the first pages dealt with ideas and theories about art and philosophy, and yet it was one of the most emotional books I’d ever read. READ MORE >

January 31st, 2011 / 12:00 am

I Can’t Really Help It: A Conversation with Ben Marcus

The following conversation between Colin Winnette (colinwinnette.com) and Ben Marcus (benmarcus.com) took place during the brutally mediocre winter of 2011. Both men carved a desk along with extra elbowroom into the walls of their unnecessary ice huts and began a steady email exchange. This was a final attempt to stay warmish. Listed below are the contents of that attempt. Special Thanks to Cassandra Troyan -The Eds.

Ben Marcus is the author of three books of fiction: Notable American Women, The Father Costume, and The Age of Wire and String. His new novel, The Flame Alphabet, will be published by Knopf in January of 2012. His stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in Harper’s, The Paris Review, The Believer, The New York Times, Salon, McSweeney’s, Time, Conjunctions, Nerve, Black Clock, Grand Street, Cabinet, Parkett, The Village Voice, Poetry, and BOMB. He is the editor of The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories, and for several years he was the fiction editor of Fence. He has recently served as the guest fiction editor for Guernica Magazine. He is a 2009 recipient of a grant for Innovative Literature from the Creative Capital Foundation. In 2008 he received the Morton Dauwen Zabel Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and he has also received a Whiting Writers Award, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in fiction, three Pushcart Prizes, and a fiction fellowship from the Howard Foundation of Brown University, where he taught for several years before joining the faculty at Columbia University’s School of the Arts.

*Portions of this interview first appeared in the Winter 2011 issue of the Tex Gallery Review

CW:Could you talk a little about your upcoming book, The Flame Alphabet? Its genesis and where things went from there?

BM: I’d been thinking for years about language as a toxic substance. Language itself making people sick. Speech and text, all of it poisonous. If you read a road sign you get nauseous. That was the original idea, but after Notable American Women I really didn’t want to write another heavily-conceptual, modular book. With that book, every new chapter felt like I was starting over. I wanted to write something continuous, a straight shot powered by one voice. I tried a lot of voices, forms, and approaches, and threw all of it away. But then I was doing some reading on underground Jewish cults and I found a pretty natural way to connect a language toxicity to a really personal narrative, even if that meant liberal falsifications and misreadings, and a story sort of bloomed fast out of that: a husband and wife who are sickened by the speech of their daughter. Literally. So sickened that they have to leave her. A situation so bad you’d have to abandon your child. This really frightened me, and I couldn’t even imagine it, which meant I had to chase it down. That was the opening premise, and once I had that I wrote the book in just over a year.

January 19th, 2011 / 1:06 pm

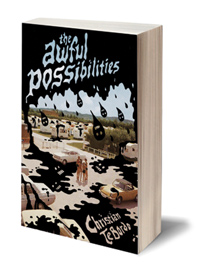

When I Turn Off My Brain: An Interview w/ Christian TeBordo

In the summer of last year, Featherproof released The Awful Possibilities, the fourth book by Philadelphia’s Christian TeBordo. It is an assemblage of extreme range in sound and direction, as TeBordo’s work manages to funnel a kind of well-orchestrated, rising mania across a range of perspectives and situations, including teenage suburban thug rappers planning a school shooting, a logic-fucked woman involved in shady black market business in a hotel, a dude trying to buy a new wallet, deathbed advice minds, and several other hybrid enactments than in other hands would lack the flair of TeBordo’s ability to funnel livelanguage and feeling into seemingly any kind of body. As says George Saunders: “Christian TeBordo shows that it is possible to be, simultaneously, a wise old soul and a crazed young terror.”

In the summer of last year, Featherproof released The Awful Possibilities, the fourth book by Philadelphia’s Christian TeBordo. It is an assemblage of extreme range in sound and direction, as TeBordo’s work manages to funnel a kind of well-orchestrated, rising mania across a range of perspectives and situations, including teenage suburban thug rappers planning a school shooting, a logic-fucked woman involved in shady black market business in a hotel, a dude trying to buy a new wallet, deathbed advice minds, and several other hybrid enactments than in other hands would lack the flair of TeBordo’s ability to funnel livelanguage and feeling into seemingly any kind of body. As says George Saunders: “Christian TeBordo shows that it is possible to be, simultaneously, a wise old soul and a crazed young terror.”

Last month, Christian and I took some time emailing about the book, Christian’s experience of influence by Brian Evenson and others, the process of assembling a text, getting along in sound and structure, approach, revision, and nudie pics.

* * *

BB: The Awful Possibilities is your first collection of short fiction after having published three novels. Do you see yourself more as a novelist, and is there a difference in your approach? Were these stories written over a long period of time?

CT: Let me answer these backwards, because that way it goes from easy to really hard. The stories in The Awful Possibilities were written over a little more than 10 years. One of the stories in there is the first I ever made that I considered a story. The most recent (the postcards), I sent to featherproof after they’d accepted the manuscript. Actually just before the book got laid out. I wrote and published my three novels during the same time. I don’t approach the forms differently when I sit down to write. For me it’s just the sentences and the persona that generates the sentences telling the larger work where to go. On the other hand, I try to do something different each time. People who read my last novel might recognize a sensibility or tendencies in The Awful Possibilities, but I hope nobody would be able to predict what one would be like having read only the other. The question of how I see myself is a little tougher. As a writer, I’m happy doing both. Stories are fun because sometimes you can just bulldoze through a draft in a sitting or two. Or you can spend weeks being really meticulous and crafty with a few paragraphs without getting disgusted by what you’re up to. Novels are fun because you have some sense of what you’re going back to each night and there’s more room to surprise yourself. The truth is, though, I feel more comfortable with short stories because I do want to be read, but I want my stuff to be an all-out assault, too, for now at least. I think people are more willing to put up with that for 10 pages than 200.

January 4th, 2011 / 2:13 pm

The Rolls Should Be Warm: An Interview w/ Michael Earl Craig

Michael Earl Craig’s third book, Thin Kimono, was recently published by Wave Books. He is one of my favorite poets. I asked him some questions when he was traveling in Michigan, but normally he is in Montana. -ZS

Michael Earl Craig’s third book, Thin Kimono, was recently published by Wave Books. He is one of my favorite poets. I asked him some questions when he was traveling in Michigan, but normally he is in Montana. -ZS

ZS: What brings you to Michigan? And what do you think about Michigan’s fudge?

MEC: The Michigan trip is for my parents’ 50th wedding anniversary. We’re in Leland, Michigan. In addition to my parents, my brother and his wife and their daughter are here, as well as my sister, her husband, and their three kids. Susan and I brought our Chia Pet, Nancy. When we were kids we’d vacation for a week (sometimes two) in this part of Michigan, so we have a lot of family history here.

And the fudge is big time in Michigan. My favorite is Murdick’s Fudge—the store in Traverse City, specifically. There are a few other Murdick’s stores but the Traverse City one is the best. I normally don’t eat fudge. Fudge is usually gritty and makes me want to knock my front teeth out on a banister. But this fudge is different. It’s creamy. It melts in your mouth (or wherever you put it). My favorite flavor is Black Cherry. Also Vanilla Chocolate Chip. And the Maple is very good. And the Chocolate/Peanut Butter. I know I sound like some sort of candy hillbilly here but it’s all true. When you eat this fudge it changes you.

ZS: What else do you eat that changes you?

MEC: Fudge is the only thing.

January 3rd, 2011 / 1:59 pm

Writers Respond: An Interview with Evan Lavender-Smith

Evan Lavender-Smith is a smart guy. Evan Lavender-Smith is, like, way too smart for me. I haven’t read Heidegger. Haven’t read Markson. Missed most of the allusions, probably. And still had fun reading From Old Notebooks. Probably everyone should read it. Everyone is reading it. All the cool people have already read it. And soon they’ll be reading Avatar, which is due out in 2011. People will be like: Q: Who’s this Evan Lavender-Smith dude wrote these asskickers? Everyone else will be all: A: Editor-in-chief of Noemi Press. Prose and drama editor of Puerto del Sol. And visiting assistant professor of English at New Mexico State University. Has awesome words in Fence, Glimmer Train, Colorado Review, Denver Quarterly, etc. And a website. www.el-s.net. You should visit it and read this interview, which was conducted using Google Docs from September 28, 2010 – October 19, 2010.

Evan Lavender-Smith is a smart guy. Evan Lavender-Smith is, like, way too smart for me. I haven’t read Heidegger. Haven’t read Markson. Missed most of the allusions, probably. And still had fun reading From Old Notebooks. Probably everyone should read it. Everyone is reading it. All the cool people have already read it. And soon they’ll be reading Avatar, which is due out in 2011. People will be like: Q: Who’s this Evan Lavender-Smith dude wrote these asskickers? Everyone else will be all: A: Editor-in-chief of Noemi Press. Prose and drama editor of Puerto del Sol. And visiting assistant professor of English at New Mexico State University. Has awesome words in Fence, Glimmer Train, Colorado Review, Denver Quarterly, etc. And a website. www.el-s.net. You should visit it and read this interview, which was conducted using Google Docs from September 28, 2010 – October 19, 2010.

1.

From Old Notebooks: How do we read it?

MOLLY GAUDRY: I’m interested in how the opening notes in From Old Notebooks (F.O.N.) help instruct the reader as to how to read this book and also sort of explain, without explanation, what this book is. READ MORE >

December 3rd, 2010 / 6:32 pm

Deus ex McFlurry: An Interview with Amelia Gray

This year saw the release of Amelia Gray’s second book, a collection of texts from FC2 called Museum of the Weird. More than a simple consolidation of stories into a single body, or even a creation of texts within the confines of one body and a strong mind, Museum of the Weird seems an object bent out of the mysterious and new, taking foreign objects, mysterious relations, freak peoples, and bringing them together in a wilding chorus of the strange and, holy shit, the entertaining, addictive. Last month I traded a bunch of emails with Amelia re: the new book, how she works, the function of belief, fate, trying, and just what the hell is with all the eating of the hair that shows up all throughout her writing.

* * *

B: Amelia, your prose has an interesting quality of being at once familiar and intuitive, while also at a seeming kind of remove: beyond just using objects and animals as active elements, there is at all times a feeling that you are way back in there somewhere, narrating your way your way rationally out of these intensely messed up, or as you say “weird,” prompts. Do you think your writing is a kind of emotional propaganda? Is all writing emotional propaganda?

A: The phrase “emotional propaganda” strikes me as redundant because any effective piece of rhetoric contains some emotional element. In propaganda and in writing there is an actor with an intent and an audience, a communicating element and a receiving element. Effective propaganda sets up a world in which only one outcome is possible in the same way that a great tragic story drives its characters towards an inescapable fate. So sure, in the way each genre stands as a completed product, writing is a kind of message propaganda that ultimately stands to aid or question a cause/idea/person. Fiction tends to attack or support ideas like love or trust or babies via scenes and characters, while war propaganda, for example–thinking of WWII posters here–attacks or supports a country or cause using ideas like love or trust or babies. There’s an emotional appeal in each, driven towards a point or points.

The biggest difference is that war propaganda or motivational speeches tend to get created with a message in mind beforehand, while fiction doesn’t have to be created in the same way (though it can be). When I write, I tend to start with a very basic idea or image (all these could be described as prompts, sure) and write my way out of it. Someone creating a political image might do the opposite–begin with a larger point and work to seek out its supporting evidence–but we end up in roughly the same place.

“Propaganda” doesn’t insinuate emptiness, nor does it have to suggest a singular message, nor does it have to be negative, but it does suggest that there’s ultimately a point to every message. Same with fiction or poetry or advertising or journalism: if a string of letters doesn’t make any words, the point might be that there’s no point, or there might be a different point, point is there’s a point.

B: Once you have your idea, say, babies, how do you go about “writing your way out of it”? How do you know when you are “out”?

A: In the story I wrote about babies called “Babies,” I started with an ordinary fear of accidental pregnancy and unwilling parents and put it into the context of an irrational fear, where the baby is immediately there and there’s no time to have serious conversations or hold a baby shower or make a doctor’s appointment. The ordinary fear combines with the irrational fear and sets off a rational string of events. Obviously the woman is going to want to clean everything up. The baby is hungry, there’s no food in the house. That’s a more comic story, things are lightly touched. I could have made it more about umbilical cord infections or traumatic blood loss or flesh ripping or whatever, but I wanted to keep the real bumping up against the unreal, babies floating inside balloons. At the end I felt the impulse to make it a happy story, where the relationship is saved and the individuals are improved, and then I felt the impulse to crush that impulse in as few words as possible, and then I felt I was out. I had the plot of that story down fast, so I remember the impulses shifting. That’s not how it always goes but it’s how it went then.

November 29th, 2010 / 1:22 pm

The Myth of the Human w/r/t David Foster Wallace’s “Mister Squishy”

Some of the most singular moments in understanding come on as if being shook: a presence entering the body unto some new consideration of how that entrance might occur. One kind of a map of a version of one’s self might be determined by considering among the terrain of the body a series of approached organs; objects imbibed, in what order, how one’s own output is affected; what is out there; what is. Seeing does this. Language, more indirectly, does this, too: entering as symbols and networks of orchestrations. Some strings of language, as well, leave in their wake a total reinvention of creation as an act, iconing on the map of self, and many selves; updating or widening or recalcifying what any kind of words can, could, or should do.

I can remember with unusual clarity the feeling in me the first time I read David Foster Wallace’s “Mister Squishy.” It was published under the name Elizabeth Klemm in the 5th issue of McSweeney’s in 2000, but by the time the magazine reached my hands I’d already heard on the Wallace listserv that this rather lengthy piece of fiction could only ever be written by him; there could have been nobody else. I was already a rabid Wallace freak; I’d pretty much begun writing fiction as a direct byproduct of reading Infinite Jest, and since then become obsessed. I read this story, long as perhaps 3 normal stories, on a futon in a house in one sitting under a skylight with legs crossed, already ready to be lit. And yet, the particular instance of “Mister Squishy,” even having then been well versed in a way that somehow placed the author’s presence in my daily thoughts (which has not since then stopped), rendered in me that the first time something different even than what I’d been ready to expect: some odd confabulation of provocation, confusion, inundated awe; a feeling rare not only for any kind of language, but particularly for a shorter work. This was something singular beyond even the already neon body of Wallace’s work in constellation, and in particular, beyond the confines of what a story as a “story,” or a novel even, or text as text, traditionally operationally assists to construe.

Since then I’ve read the 63 pages of “Mister Squishy” at least a dozen times. I’m not sure even still I can begin to wholly how to parse the innumerable levels of its moves, using tactics and employments that continue shifting with each reconsideration and further study in the way a Magic Eye painting might if it could get up and walk around: a kind of high water mark of contained language and ambition, since then, now ten years later, still uncontested in the ways of invoking the uninvocable, the void. It is a station, I believe, should be reexamined; it is, in many ways, a kind of key to a beyond, both in the content of the story, and the method of its opening a new kind of affect in languageground, one that still has yet to be, these years later, fully inculcated, or because of time’s way, even unpacked.

November 22nd, 2010 / 11:32 am

Time Traveling with Josh Russell: An Interview

The risk, lyricism, and page-turning plot of Josh Russell’s Yellow Jack appear again with maturity and elegance in his second novel of historical fiction, My Bright Midnight. How? Why? With what nerve? Josh Russell, recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship and Co-Director of Georgia State University’s Creative Writing Program, reveals a secret or two.

Q: Aimee Bender wrote, “Everything a human experiences happens on the body. That’s enough setting for me.” Your protagonist Walter is very self-consciously embodied after leaving Germany and experiencing life in 1930’s and 40’s New Orleans, which you imbue with its own highly sensual body. Would you discuss the way the settings (or bodies) worked together in your process of writing the novel?

Q: Aimee Bender wrote, “Everything a human experiences happens on the body. That’s enough setting for me.” Your protagonist Walter is very self-consciously embodied after leaving Germany and experiencing life in 1930’s and 40’s New Orleans, which you imbue with its own highly sensual body. Would you discuss the way the settings (or bodies) worked together in your process of writing the novel?

A: A few days ago I was commiserating with a friend about commuting and how we both missed being able to walk to work, and I was amused and amazed to realize how related writing and walking are for me. I wrote Yellow Jack while walking during two years of lunch hours when I was working as a help desk dispatcher: Walk a few yards along the path beside Boulder Creek, stop, write a sentence in my notebook. Walk a few more yards, stop, write two sentences. I would have had a lot less to write about had I not spent so much time walking to and from work when I lived in New Orleans a few years before I began even thinking about Yellow Jack. My Bright Midnight comes in large part from my second, longer, residence in New Orleans, during which I regularly walked the twenty-odd blocks of Magazine Street between my house and Tulane University, where I was working, stopping to buy pain raisin at the neighborhood boulangerie, cafe au lait at the coffee shop, and blood oranges at Whole Foods (it’s amazing to recall that this did not seem in the least pretentious). Obviously the New Orleans landscape is an important part of both books. As for how settings and bodies worked in my process of writing My Bright Midnight, when I choose to write something with an historical setting, I do so in part because of the challenges of avoiding clichés about the past, and one strategy I employ to answer those challenges is to make sure that the characters’ interiors and exteriors are never lazily constructed.

November 2nd, 2010 / 11:43 am

Neck Goozle or Adult Acne: An Interview with Lindsay Hunter

This Fall saw the release of the debut collection from one Lindsay Hunter, aptly and majestically titled Daddy’s. If you’ve ever seen Lindsay read in person you probably were hiding in your closet with your head between your legs covering your junk quivering about this monster, a collection of short texts trapped inside a tackle box. Lindsay’s language is somehow both frightening, gut-bunching, weirdo, home, cover your face, open your mouth, transcendent, and of heaving sound. At times like if Gummo turned into words and date-raped Mary Gaitskill’s language then went to the gas station to buy tissues to clean up the messies and bought you a snack of discount heat lamp chicken. Underneath it all, this weird American convulsive heart that sounds like someone if we haven’t been, at least we remember getting beaten up in middle school.

Over email, so as to not get bit, I traded q’s with Ms. Hunter re: the book, humor, music, inspiration, fear, performance, and all the rest.

BB: I love how Daddy’s operates in reading almost as a series of rotations in a brain of what some would call trash life: each of the stories in the collection often concerns sex, food, and body fluids. The sky is referred to in turns from piece to piece as if it is shifting through a section of a place that does not change: and yet each story feels so singular. Was this variation something you were super aware of while you were writing the stories, or did the voices just keep coming out? By what means was this book written?

LH: I don’t know that I was aware of this as I was writing each story, but looking at the book as a whole, it definitely feels like there is a town in which these people live and it is the same town. I generally start with the first line of something and then see where that leads me. I’ll have first lines in my head for days, or sometimes I’ll get one and I’ll need to sit down and just fucking follow it. Every now and again I’ll have an idea for a story, like some kind of situation or glimpse–like in “That Baby” I wanted to write about the jealousy of babies–and I’ll wedge my way in and try to write what I see.

I think these stories are what they are because I tend to go sentence by sentence and edit as I’m writing–I can’t move on until each sentence is just right, and if I’m bored by a line it feels wonderful just to delete it and start over. That’s my main thing–I hate boredom and being bored and boring writing and cliches and puns and double entendres and cleverness. So I try to eviscerate all of that. But watch, I’ll open up my book and see the phrase “and that was the end of that” or “new lease on life” or “make love” and I’ll have to face some pretty ugly truths about my inner life.

October 18th, 2010 / 12:16 pm

An Interview with Birds, LLC

The editors of Birds, LLC were kind enough to answer a few questions this summer about their unconventional editorial process and what went into Trees.

The editors of Birds, LLC were kind enough to answer a few questions this summer about their unconventional editorial process and what went into Trees.

Joe Hall: How is Birds, LLC’s editorial process different than that of other independent presses? & what made you want to foreground the editorial process?

Dan Boehl: The way we approached the editorial process was to say, “Let’s be awesome and do dope shit.” We knew that Chris and Elisa had great manuscripts, but they are not getting published anywhere. Once we decided on the authors, we looked at the manuscripts and decided to make them be awesome. It took a lot of work. Each manuscript was assigned an editor. Justin for Chris, and Sam for Elisa. After the assignments, all the Birds editors read both manuscripts and gave feedback. Then a new manuscript was created by the poet/editor combo, and we repeated the process.

Chris Tonelli: i think we’re just kind of old fashioned. we want to spend a lot of time with the author and designer to help make that happen. each book is assigned a lead editor based on a variety of things, and he and the author, with feed back from the other four editors, work up new versions until everyone is satisfied. same with the design…the editors and designer work up versions to show the author and make changes as necessary. nothing fancy. but with so many friends unhappy with how their presses have edited, designed, and promoted their books, it does seem kind of novel…with a few exceptions.

October 13th, 2010 / 2:27 pm