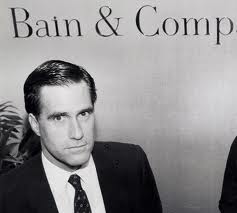

The Chronicles of Mitt

If you haven’t been reading the ongoing Chronicles of Mitt at Daily Kos, you’ve really been missing out:

I no longer feel confident that I want to be president. Why was I running again? There was the tax cut, but surely it would have cost less money for my fellow wealth units and I to simply purchase sufficient lobbyists to obtain it. Now in order to satisfy critics I have had to claim that my singular goal, a very large tax cut, would not actually cut taxes. That is, in all of this, the one policy alteration that I cannot abide. I do not care about the other things—the nonsense about “ObamaCare,” the being angry with China, and the other things are all merely strategic calculations, but the very large tax cut for myself was the one policy out of all of them that I had designed myself, and that I felt strongly about. I spent many an evening explaining to Ann how I would carefully reapportion the money from our very large tax cut into each of our various accounts. To disown it feels like I have disowned a child. A particularly good and uproarious child, like Tagg, not one of the others.

The archive’s here.

“I know you can’t wash in the same river even once / I know the river will bring new lights you’ll never see”

Thanks to Amy King for posting on her Facebook a link to the poem “On Living” by Nazim Hikmet, which I read, which made me read all of his poems I could find online, and later I am going to go to Amherst Books to buy a copy of his collected poems before someone else does. Probably you’re so smart and ride such a brakeless bicycle that you already knew about this guy, because even Joan Baez knows about him, and he has his own festival and portrait of himself writing in prison and is Turkey’s most famous poet, so probably you already knew all that, but I didn’t, and if like me you woke up today not having read “On Living” and “Things I Didn’t Know I Loved,” you should go ahead and do that. And even if you have read them, seems like a good idea to kiss your knuckles for good luck before you get on your brakeless bike and read them again.

Thanks to Amy King for posting on her Facebook a link to the poem “On Living” by Nazim Hikmet, which I read, which made me read all of his poems I could find online, and later I am going to go to Amherst Books to buy a copy of his collected poems before someone else does. Probably you’re so smart and ride such a brakeless bicycle that you already knew about this guy, because even Joan Baez knows about him, and he has his own festival and portrait of himself writing in prison and is Turkey’s most famous poet, so probably you already knew all that, but I didn’t, and if like me you woke up today not having read “On Living” and “Things I Didn’t Know I Loved,” you should go ahead and do that. And even if you have read them, seems like a good idea to kiss your knuckles for good luck before you get on your brakeless bike and read them again.

DIED: Keith Campbell

On October 5, Keith Campbell—one of the scientists who worked on Dolly the sheep, the first mammal cloned from an adult cell—died at the age of 58.

Adult cells have specialized jobs. They make one thing—skin, for example. Embryonic cells are not specialized. So, making an entire body from an embryonic cell is relatively easy. Making an entire body from a specialized cell is not. Campbell suggested trying to find a way to get adult cells to revert, to forget their specialization. Starving the adult cell did the trick. Dolly followed.

Some people call cloning “playing God.” Mostly, those people are talking about human cloning, not animal cloning.

But, still, Dolly caused a stir. And accusations of playing god. READ MORE >

I Am Prepared to Read Many More Novels About People Fucking

I haven’t read Sheila Heti or Ben Lerner’s recent novels, the impetuses for Blake Butler’s recent, anti-realism-themed Vice article, but I’d like to respond to Blake’s finely-written itemized essay, because I, personally, continue to desire novels written by humans, which relate, slipperily or not, to human reality—subjective, strange and ephemeral as it is–novels which deal with such humdrums as sex, boredom, relationships, Gchat, longing, and, beneath all, death. I want a morbid realism.

I agree with Blake that a reality show like The Hills and social media such as Facebook create stories by virtue of humans doing simply anything. The documenting, sharing, and promoting of mundane everyday human life is more prevalent and relentless than ever before. In this environment, literature (and movies) about humans (most controversially, about privileged, white, hetero humans) that presents everyday drank-beers-at-my-friend’s-apartment life, wallows in self-pitying romantic angst, and doggy paddles po-faced through mighty rivers of deeply profound ennui can potentially seem annoying, or boring, or shittastical.

Birds Blur Together

R.M. O’Brien and Lesser Gonzalez-Alvarez are two wicked awesome Baltimore multidisciplinary artists who recently collaborated on a quiet, handsome little book of poems called Birds Blur Together (buy it for $6 here). Look at that cover—tell me it doesn’t look like something missionaries would hand out in South America? R.M., who runs the great reading series WORMS, put the 25-poem book out on his own WORMS PRESS because he can do whatever the fuck he wants to do. Like, just check out this video of his old band Nuclear Power Pants. Bob gots the beard and the stabby back. READ MORE >

R.M. O’Brien and Lesser Gonzalez-Alvarez are two wicked awesome Baltimore multidisciplinary artists who recently collaborated on a quiet, handsome little book of poems called Birds Blur Together (buy it for $6 here). Look at that cover—tell me it doesn’t look like something missionaries would hand out in South America? R.M., who runs the great reading series WORMS, put the 25-poem book out on his own WORMS PRESS because he can do whatever the fuck he wants to do. Like, just check out this video of his old band Nuclear Power Pants. Bob gots the beard and the stabby back. READ MORE >

R.I.P. Carlos Fuentes. I just found out. He was one of the greats. Places to start if you haven’t read him: Where the Air Is Clear (1958), The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962), Terra Nostra (1975). & here he is on the BBC (audio), and here are various YouTube videos.

Godspeed, good sir.

RIP Maurice Sendak

Progress vs. Catastrophe: Underworld by and beyond Benjamin’s Angel of History

A Brief Introduction to the Themes

In 1940, Walter Benjamin published an essay, consisting of a collection of brief reflections, titled “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” The ninth thesis describes Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, in which an angel “look[s] as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating” (Benjamin 257). Benjamin links this to “the angel of history” observing the world through the position of the past. While the future pushes on inevitably—insists he take notice—the angel is turned away, caught up in the disasters of the past. This overseer wants to arrest the present, stop progress altogether in order to amend the disasters and failures of history, and finds itself in a struggle against the powerful reality of the ever-advancing state of existence. Thus, a rivalry between progress and catastrophe is established.

Don DeLillo’s 1997 magnum opus Underworld meditates heavily on Benjamin’s ninth thesis. The progress of society, through the lens of the Cold War begins in 1951 and is presented in reverse chronological order, backwards from 1992, after the complete dissolution of the Eastern Bloc. The undulating anxiety regarding Western society’s seemingly imminent doom is displaced by an anxiety within the context of the American Dream. Baseball, bureaucracy, sex, waste, art, religion, and crime take on the weight of the present’s baggage through the obsessive compulsions of the past.

There is no direct solution to the conflict of Benjamin’s thesis, just as DeLillo offers little individual resolution for his characters. However, the driving force of salvation, the one in which we thrust our faith and loyalty, is the same in both dilemmas: the angel. The angel of history is trapped in a moral and physical bind; it seeks some way in which to move on from humanity’s historical failings—the “single catastrophe”—and to avoid, or amend, the forthcoming quandaries of the world—the “storm” (257-8). DeLillo’s angel, Esmeralda, extends this notion further, and acts as a Christ-like sacrifice for history and an entity from which to begin anew, look around, and turn toward progress.