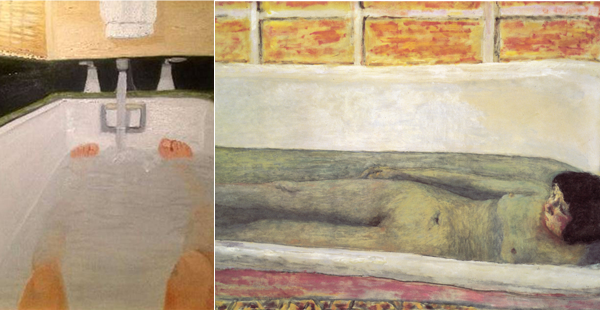

Ben & Amy Read Chapbooks (Miscellaneous Stuff Edition)

Amy Lawless and I like to read chapbooks and review them on the internet. We used to write these together, while drinking wine and watching TV. We live in different cities now, so we do them over gchat. Here are our recent reviews:

Review 1: The Wikipedia Page for Tears

“boy with mullet, crying”

Amy: HEY

Sent at 1:23 PM on Sunday

me: yo

Amy: we did it

me: ya good job

Amy: ha

OK

me: lets get into it. what’s the first item

Amy: The Wikipedia Page for Tears:

ttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tears

Let’s both look at the page and go for it.

Public Collection

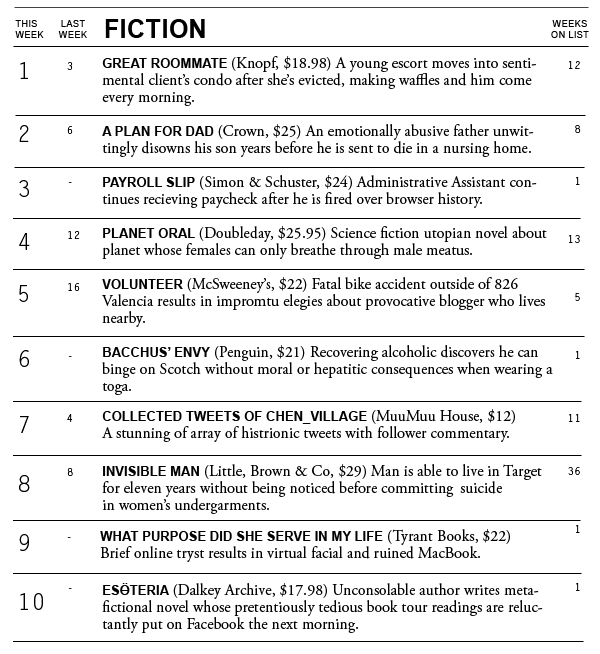

Of a kind of modesty far disproportionate to the attention it’s getting — for it would take a hacker to get into our former president’s sister’s email — amateur yet keenly perceptive paintings by George W. Bush have surfaced. They are remarkable: not so much their rendering or skill, but in their quiet internal repose, evocative of the peculiarities of the Nabis post-impressionist school. An immediate, and easy association — if one considers their respective and mindless havoc onto their perceived enemies — is Adolf Hitler, who also produced unexpected touching watercolors of churches. The imperial hubris with which Bush demonized Afghanistan at large, and later Iraq, is a sad example of turning the enemy into an abstraction. The same can be said for liberal media in their inclines against Bush; and so now, it seems, we are perplexed, and very taken aback at being allowed to see this man in a different light. It is simply hard to imagine such a heartless war monger painting such gentle paintings. Yet, the disparity lies not with Bush’s character, but the assumption that artists are somehow — by the very auspices of their art, as if introverted pastime were a moral act — essentially good people. Enter Pierre Bonnard, whose codependent relationship with his wife Marthe has kind of hilariously been documented by the many paintings of the her in the bathtub. She is said to have suffered from OCD and compulsively bathed half-a-dozen times a day, as if trying to wash away the dabs of paint for which she might have been mistaken by her husband. The pairing here is at best merely coincidental, until we look at their perspectives: George W. Bush gives us his own POV, as autoerotic muse, his phallac member just off the bottom of the canvas, perhaps the rod-like stream of water a surrogate hard on. This is the same view Marthe was having back around 1935, and toggling between the two collapses us into a kind of he-said-she-said scenario, of different versions of the same history.

Dating Siri

With the release of Siri, an “intelligent personal assistant” app introduced in iOS6, Apple took a unique marketing approach, that of entitled idleness. We see John Malkovich, a cloud of constant irony around him, seated at home skeptically saying “life” into his phone. Siri then offers this advice: try and be nice to people; avoiding eating fat; read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, etc. (c.f. “Fitter Happier,” OK Computer). It’s as if the ad were making fun of the app, bowing to the absurdity of first world problems gone amuck, which is a peculiar move for Apple, whose ads are usually literal and almost condescendingly simplistic (e.g. dancing silhouettes, sincere FaceTime). The camera takes long pans of his house, giving into a kind of bourgeois, somewhat sad reverie: the tempting light of a good day yawning through the panes, the modern art hung salon style on the walls, a suit jacket flayed open to let the smallest gut out. There is even a faint air of derision. Vilhelm Hammershøi, a Danish late 19th century minor painter, made banal paintings in the then climate of fierce modernism; they were sentimental and weak-handed, simply not a match for the explosiveness of his more devastated peers. There’s a clear homage to Vermeer, and one may see him as a precursor Edward Hopper, but overall it’s rather forgettable. He painted his house from a dozen angles, repainting the same scene a year or so apart, his averted subjects slightly older, and having wandered elsewhere. The movement of light across the floor was more of an event, sans notifications and likes. People were walking sundials, the radius of their slow shadows boring as fuck. They knitted, read, and died early.

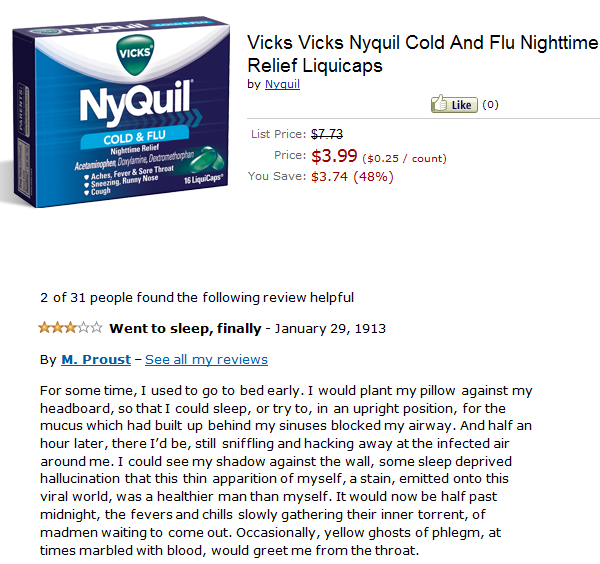

CONFESSIONS OF A SLEEPREADER

The time I set aside for pleasure reading has become, in a word, unpleasant. Like you, I have obligations that irritate the ulcers. Bills to pay, a job to attend, a body to take care of, domestic insects to kill or exterminate. The other day I had to rest a glass of apple vinegar atop my bedroom dresser to trap gnats (they love the stuff—who knew?). My girlfriend was “seriously convinced”it was a glass of pee.

Among the detritus of everyday life, like contributing to the genocide of bugs, it’s often nice to turn to the literary big hitters for a respite from the banal. We let Nicholson Baker make us feel dirty; allow Mark Twain to make us laugh; invite Poe to exercise our imaginations and neuroses. If only we didn’t stab them in the back.

While I do happen to harbor my fair share of neuroses, my particular irrational fixations fortunately do not pervade my End of the Day Time to Go To Bed times. I like sleeping and I like walking, but I’ve never sleepwalked. I’m no psychiatrist, but it seems to me a condition afflicting those whose adventures in waking life have taken a turn for the disenchanted. Having the fortune of sound sleep, it’s hard to relate to the woes of the sleepwalker, or, as a matter of fact, any rigors of debilitating nocturnal activity (sleep eating, sleep apnea, sleep talking, sleep onanism, the grinding of the jaw, or that kind of bodily sprawl that ends with a dull, but loud THUD as a loved one graces the floor). But I can speculate that the body does these things to reconcile anxieties. Among which lies boredom.

From my past as a musician with a practice-until-your-fingers-bleed type dedication, I know that an in and out, day after day routine can bludgeon one’s piece of mind. In the 1960’s Guy Debord, a French Situationalist, imagined a serum for this kind of anxiety. Debord conceptualized Dérive, an experimental behavior that encourages one to make new what has become plebian, everyday, boring. Normally, this is done by making urban landscapes exciting again by drifting (literally, walking) through the city, taking directional cues not through street signs, but through the contours of the town’s architecture. Just kind of feeling your way out through new, unexplored terrain to invigorate the drifter from routine. There is no destination; only, perhaps, in the mind: to find something out about yourself and your city. Debord encourages getting hammered beforehand.

Lines from Shakespeare Mistaken for 1990s Hip Hop Lyrics

“I’ll teach you how to flow.” (The Tempest)

“He speaks plain cannon fire, and smoke and bounce.” (King John)

“I have within my mind / A thousand raw tricks of these bragging Jacks, / Which I will practise.” (The Merchant of Venice)

“That’s an ill phrase.” (Hamlet)

“Holla, holla!” (King Lear)

READ MORE >

DIED: The Verbessem Brothers

Marc and Eddy were deaf and learned that soon they would both go blind. They were 45 and twins. Because they were Belgian, the option of assisted suicide was available to them. Believing they would no longer be able to live self-sufficiently, and to communicate with each other and family (they had developed their own sign language), they chose death by lethal injection. Before they died, they had coffee. READ MORE >

The Joys of Oral History

Life is not organized, logical, or factually accurate. Yet we require this of our history books, which must contain names, dates, verifiable pieces of evidence, and claims about cause-and-effect. Event A leads to Event B. Event C happened on December 15th, 1910. Person X was at Place Y During The Conflict of Z. It can all get rather drab and unrealistic. There is something particularly dulling about reading a list of dates and proper nouns and thinking these alone compose our lives. Where’s the hilarity, hurt, daily bafflement, and sense of fun? History books miss out on a lot, particularly the general pell-mell-ness that pervades life, where cause-and-effect is displaced by the indecipherable and happenstance forces that influence our actions and beliefs. This is why oral histories rule.

Oral histories are collections of voices all jousting to be heard. Whether they’re about a life, an era, or a single event, oral histories convey the necessary complexity, where details collide and thesis statements don’t matter. They are messy, chaotic, and incongruent—patchwork quilts of anecdotes, recollections, non-sequitors, and stories that begin with a promise but don’t really end, stories filled with incorrect information, nostalgia for even the worst events, positive memories of mean people, and much more, stories stuffed with dreams, debris, and insignificant moments—the true fabric of the history.

Here are 5 great oral histories:

Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk, by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain

Please Kill Me is a wicked traipse through the gutter-glamour of ’70s New York. There’s Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Handsome Dick Manitoba, Jayne (né Wayne) County, and the Ramones, plus a whole slue of record industry insiders, drug addicts, scenesters and weirdoes. The music is great and the talk uproarious. From tales of Jim Morrison’s depravity to anecdotes about those doomed birds Sid and Nancy, there is something for everyone in Please Kill Me. “There was never a yesterday or a tomorrow,” says one punk rocker. Only an insane today. This book is funny, gross, and outrageous, an underground oral history that is a riot of voices.