In defense of romance novels

Piggybacking on Mike’s earlier post, I have long found it curious that the romance novel is the one genre no one wants to defend. (See, for instance, this comment.) But time was, romance was the genre.

Piggybacking on Mike’s earlier post, I have long found it curious that the romance novel is the one genre no one wants to defend. (See, for instance, this comment.) But time was, romance was the genre.

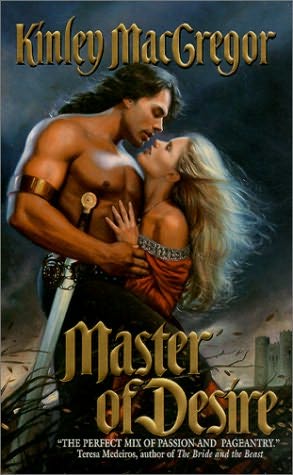

It seems to me that the contemporary romance novel—of the paperback bodice ripper variety (see right)—arrived on our shores of our literary imagination in no small part due to writers like D. H. Lawrence. And what could be more literary than Lawrence? I myself can conceive of no formal reason why a romance novel can’t be art. Indeed, I suspect that someone out there is already writing great ones. (Hell, isn’t Lolita a romance novel?)

Part of what I love about this Chicago Reader review of The Twilight Saga: Eclipse is its understanding of how Stephanie Meyers’s books and the resulting films—regardless of their quality (I haven’t read or seen them yet, though I intend to)—do partake of a larger literary tradition:

Meyer’s genius (if you want to call it that) is having figured out how to repurpose the same old cliches for an era in which even tweens may occasionally feel embarrassed about fetishizing people at the top or bottom of the social scale. Edward has gobs of money and cultural capital, but the fans will tell you the reason he’s enchanting is because he’s immortal and mysterious and goes all sparkly in the sun. Jacob is exciting and exotic because he’s living close to the land, but the fans will tell you it’s because he’s impulsive and physically powerful. The two of them would like to kill each other, but as Meyer would have it, that’s simply because vampires don’t like werewolves. In the novels, when Jacob calls Edward a bloodsucker and Edward calls Jacob a dog, these are not epithets of the class struggle but literal descriptions.

Me, I’m all for genre. As I wrote in this post, the question of whether works of genre can be art doesn’t exist in cinema, and I think that puts the lie to the issue in literature:

“Just think about it: A Trip to the Moon, The Great Train Robbery, The Birth of a Nation, Nosferatu, Metropolis, Love Me Tonight, Trouble in Paradise, Duck Soup, Bringing Up Baby, The Maltese Falcon, Cat People, Heaven Can Wait, The Seventh Victim, Out of the Past, The Third Man, Sunset Blvd., The Asphalt Jungle, Johnny Guitar, Kiss Me Deadly, The Night of the Hunter, The Searchers, Written on the Wind, Touch of Evil, Vertigo, Sweet Smell of Success, North by Northwest, Rio Bravo, Some Like It Hot, Breathless, Yojimbo, La jetée, Charade, Point Blank, 2001, Rosemary’s Baby, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Two-Lane Blacktop, Solyaris, Don’t Look Now, The Godfather Part II, Night Moves, The Man Who Fell to Earth, The Empire Strikes Back, The Shining, Blade Runner, Blue Velvet, Goodfellas, Dead Man, Babe: Pig in the City, The Thin Red Line, The Limey… all widely regarded as great works of art, and all indisputably genre films. I mean, no one in cinema ever says anything as laughable as, ‘2001, great movie—but of course it’s not really science-fiction…’”

Many of the best movies have been romances: Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, City Lights, Love Me Tonight, Trouble in Paradise, Bringing Up Baby, The Bitter Tea of General Yen, The Scarlet Empress, It Happened One Night, Gone with the Wind, His Girl Friday, Ninotchka, Rebecca, The Philadelphia Story, The Shop Around the Corner, Casablanca, Heaven Can Wait, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, To Have and Have Not, Beauty and the Beast, Laura, ‘I Know Where I’m Going!’, Stairway to Heaven, Brief Encounter, The Red Shoes, In a Lonely Place, Written on the Wind, The Cranes Are Flying, Vertigo, Hiroshima Mon Amour, Breathless, Last Year at Marienbad, Splendor in the Grass, Jules and Jim, L’Eclisse, Charade, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, The Graduate, Little Murders, Love in the Afternoon, The Heartbreak Kid, The Mother and the Whore, Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, Annie Hall, That Obscure Object of Desire, Manhattan, Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession, The Princess Bride, Wings of Desire, Ashik Kerib, When Harry Met Sally, The Double Life of Veronique, Orlando, Groundhog Day, Chungking Express, Love Letter, Open Your Eyes, Lovers of the Arctic Circle, Yi Yi, In the Mood for Love, What Time Is It There?, Last Life in the Universe, Howl’s Moving Castle, 3-Iron, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, …

Sooner or later, someone’s going to revitalize literary romance, either by making some great new work in the genre, or by discovering an existing great contemporary romance novelist who will then get added to the ranks of great “pure genre” writers like Agatha Christie, Raymond Chandler, Patricia Highsmith, Jim Thompson, Jack Vance, Philip K. Dick, Barry N. Malzberg, Dave Sim, Frank Miller, Alan Moore, … (Or … both!)

For a while now I’ve been dreaming of writing a romance novel, a formally innovative and yet broadly accessible romance piece of fiction … I have what I think is a very good idea for one. Well, we shall see.

… This has been much on my mind, because I just got a copy of John Norman’s Imaginative Sex (1974). I’ve long wanted to write something about his Gor novels, and the BDSM subculture they spawned… (literary representations of sex and fantasy being two of my primary interests!)

In the meantime, if you know of any great romance writers/novels, by all means, please chime in! For my own part, I will propose that the following are both great and, in their own ways, romance novels (and this is HARDLY meant as definitive—and I don’t expect you to agree that these are all typical romance novels—but when are we interested in the typical? And I do think a case could be made for all of them):

- John O’Hara, Appointment in Samarra (1934)

- Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

- Jane Bowles, Two Serious Ladies (1943)

- Paul Bowles, The Sheltering Sky (1949)

- Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (1955)

- Alain Robbe-Grillet, La Jalousie (1957)

- Richard Yates, Revolutionary Road (1961)

- Kōbō Abe, The Woman in the Dunes (1962)

- Nicholas Mosley, Impossible Object (1968)

- Ann Quin, Passages (1969)

- Marguerite Duras, Destroy, She Said (1969)

- Marguerite Duras, The Lover (1971)

- Ann Quin, Tripticks (1972)

- Harry Mathews, The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium (1975)

- David Markson, Springer’s Progress (1977)

- Italo Calvino, If on a winter’s night a traveler… (1979/1981)

- Margeurite Duras, The Malady of Death (1982/1986)

- Harry Mathews, Singular Pleasures (1983)

- Kathy Acker, Blood and Guts in High School (1984)

- Hilary Mantel, Every Day Is Mother’s Day (1985)

- Hilary Mantel, Vacant Possession (1986)

- Dave Sim & Gerhard, Cerebus: Jaka’s Story (1990)

- Yuriy Tarnawsky, Three Blondes and Death (1993)

- Harry Mathews, Cigarettes (1987)

- Carole Maso, The Art Lover (1990)

- Mati Unt, Things in the Night (1994/2006)

- Michael Kelly, Ulrich Haarbürste’s Novel of Roy Orbison in Cling-film (2007)

- Jeremy M. Davies, Rose Alley (2009)

- Tao Lin, Richard Yates (2010)

… Your thoughts?

Tags: D. H. Lawrence, genre, Kinley MacGregor, Lolita, mike meginnis, Noah Berlatsky, romance cinema, romance novels, Twilight

I think that the point is not whether a crime, fantasy, sci-fi, horror, western or romance novel can be Great Literature. Everyone, including Krystal, could come up with works that meet the specifications of these genres and yet are accepted as Literature. Many, however, would think that these works are nearly exclusively written by “literary” authors outside the circuit of genre fiction proper, because the commercial nature of genres brings a set of expectations, on formal and stylistic terms, which stifle experimentation and original expression sraitjacketing writers to a few tried and true patterns.

Now, while this might be true in general, many others would argue that most genres provide a wide enough tent to allow for the existence, perhaps in the margins or outside true commercial success, of idiosyncratic voices and unorthodox approaches: Shirley Jackson Robert Aickman or Thomas Ligotti in the Horror genre, Patricia Highsmith Jim Thompson Willeford or Simenon for Crime, Charles Portis for Westerns, and many in the F/Sf genres, which are, at least potentially if not in actuality, the most diverse.

When it comes to Romance, however, there’s a sense that the borders are patrolled more strictly, and perhaps works that deviate from the norm – stories with love, rather than love stories – are more easily sold and marketed as General or Literary Fiction. For instance, the Romance Writers of America establishes a happy ending as a prerequisite for Romances (something which would exclude Romeo and Juliet, the most popular romantic story of all time); stories in which the criminal escapes or the mystery remains unsolved, meanwhile, even though neither frequent nor loved by everyone, have always been accepted by crime/pulp imprints.

my mom has thousands of paperback romances. when i was a little kid i always liked the covers, and as presents i would buy her books based on the period costume the woman was wearing on the cover, i mostly chose books with women wearing blue.

paperback romances, without exception, adhere to a rather stringent formula. i.e. the ‘virgin deflowering’ scene occurs between chapters 13-15, and this scene is where the author goes to great simile-ridden lengths to describe sex in the most languidly sensual tone possible: “she fit the length of his throbbing member like a well-oiled glove” is a bit i remember. there’s always a great line about the ‘taut rosy buds of her nipples’ or something, her nipples are either a fruit or a flower. orgasm is usually likened to a flood of warmth.

the sex is drawn out for the entire chapter and no congruous language exists in the rest of the book, which is weirdly dry and laden with dialogue. conflict is usually related to class struggle or parents. i think nora roberts is one of the more famous ladies who writes these, and she is a person who also writes murder-mysteries under a vaguely male pseudonym.

my favorite ‘romances’ are Goethe’s Werther and Zola’s Germinal + Therese Raquin, Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, Waugh’s Brideshead, and i also think that a lot of Genet’s stuff is quite of gorgeously romance-y.

I think you really nail something there (and thanks for the additional titles). I’ve long wondered why other popular genres (sci-fi, mystery, detective, western, fantasy) could be rehabilitated and “made literary,” but romance couldn’t. And I think now it’s precisely because people identify romance exclusively with formulaic product like Harlequin. Which would be like equating mystery novels with the Hardy Boys.

Here’s the thing, though. Formulas offer great potential for deviation, and for surprising artistry. For every 10 hacks who simply follow the formula, someone is going to try to subvert the system. That’s just human nature!

For instance, consider the Choose Your Own Adventure novels. They were very formulaic; the publisher even provided the decision trees to the writers. (Here’s an excellent analysis of how it was done.) But at least one CYOA author, Edward Packard, managed to do some wacky stuff with that—see the amazing “ultima” ending of his CYOA novel Inside UFO 54-40 (it’s at the bottom of that site with the analysis).

So my suspicion is that someone out there has to be doing something subversive with the Harlequin formula. But who is it?

Meanwhile, as long as folks continue to insist that Harlequin comprises the entirety of romance writing, then romance writing will (mostly rightly) be considered something awful. But why do we insist on that distinction? We recognize that the Hardy Boys are but one (very formulaic) type of mystery writing, churned out by Stratemeyer’s machine. But, meanwhile, Agatha Christie existed, and she wrote works like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and Endless Night, mystery novels that innovated with the conventions of the genre.

Thanks for chiming in!

Me, I really dislike that move wherein the good writers are yanked out of the genre, and called literary, and are therefore no longer genre writers. Patricia Highsmith wrote suspense thrillers! She worked in that genre! She was also one of the best writers of the 20th century, in my estimation—I prefer her to Kafka, quite frankly.

That maneuver (which I note you’re describing and not necessarily endorsing) reminds me of how people who dislike comics tend to decry their quality, then say, “But I like this graphic novel.” As though a graphic novel weren’t a comic!

Philip K. Dick was a science fiction writer! He managed to transcend many of the limitations of the form, and produce many brilliant novels. But to insist then that he wasn’t a sci-fi author is to do exactly what Mike Meginnis so rightly calls Krystal out on—it’s to determine, a priori, that the genre can’t be literary. (And so anyone who does good work in the genre can’t therefore belong to it, because the genre is, by definition, bad.)

Most writing out there is bad. I take and teach writing workshops, and read a lot of lit journals, and most MFA/MA/PhD “literary” writing is bad, bad, bad. Maybe those of us who like genre fiction should start poaching writers from that scene. “Thomas Pynchon, what a great sci-fi writer. Not really a literary fiction guy, though, because unlike most of the people in that crowd, he was actually good!”

In my estimation, expectations of form and style are no enemy to art. Quite the opposite: they are the fertile ground in which art takes root. It may be true that some specific editor or publisher somewhere stifles innovation, or original expression, but that has no consequence for the genre itself. (That’s no different than if your teacher insists you write a shitty five-paragraph essay. It doesn’t mean the essay form is debased. It means you have a bad teacher.)

Marvel Comics was as factory-like a production studio as anyone can imagine, churning out endless pages of crap throughout the 1980s. Frank Miller still managed to make his Daredevil comics there.

A lot of great art comes about because people are trying to challenge perceived limitations regarding what’s possible. As Magic’s Head Designer Mark Rosewater puts it, “Constraints breed creativity.” The Oulipo agree. As Harry Mathews has often said, Georges Perec once gave himself permission to write anything he wanted, without any constraints. He couldn’t produce anything.

I’ve said it 1,000,000 times already, but I really love this recent essay by Nicholas Brown, which is a defense of the artistic (and anti-capitalist) potential offered by genre.

Cheers,

Adam

Here we go again :-) What exactly is a “romance novel”?

Adam, how many typical readers of romance novels would consider “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler” or “Blood and Guts in High School” to be romance novels? Or Samuel Delany’s Dhalgren?

Bill

p.s.: I don’t like the term “literature” either. Couldn’t we just talk about “texts”?

I can’t imagine that guy’s AC is very good, regardless of his DEX score. I mean, not even a chest plate?

Seems like a lousy tank.

I’ve mentioned this elsewhere, but one of the first decent books I read as a kid was Tamora Pierce’s The Song of the Lioness series, which if I recall correctly certainly had a lot of the markers of the romance genre, though it’s typically classified as fantasy (and, if Wikipedia is to be believed, YA, though that’s a bit of a surprise to me). My tastes have shifted a lot since then and I’m not sure I’d be able to enjoy them in the same way now, but man, those books were fun — and, if memory serves, one or two bodices may have even been injured.

Looks like he holds aggro pretty well though.

You’ve both hinted at what I see as the main issue about genres: they all started before mass marketing (except maybe westerns, but I might call them a well-worn niche of adventure stories, which predate mass marketing.) Therefore what people bemoan about ‘genre writing’ is its debasement, not its essence. That’s how I see it anyway. In other words, the decades of market-flooding cheap paperbacks cemented the tropes which people wrongfully believe are essential to each genre’s very nature.

What am I missing?

Your posts are interesting enough, but you always sort of belabor the

same points. I feel like you are a kid or something, finally discovering that genre

is where a lot of great art begins, and then you predictably bring it back to comics.

Okay I’m just critiquing this for the hell of it, I’m not upset or anything.

But maybe you could do more than try to convince your audience of the validity of genre?

As someone who’s read all the Twilight books I found the excerpt you posted—the analysis of Twilight—as the most compelling part of this post. Whoever wrote that excerpt was spot on, about the social values of the characters.

seems to me he is maintaining a low equip burden to enable quick-roll. two-hand that bastard sword–and yes, a high DEX score would certainly help–and he could do some pretty swift damage.

those muscles lead me to believe he’s less of a tank, and more of a straight-up quality build.

He’s wearing a Condom of Protection +4.

Save vs Clap

Ford Madox Ford, The Good Soldier

He has a very long and shiny sword. That has to count for something.

That sounds right to me. I actually don’t know when “genres” started, and keep meaning to investigate it. Are they just marketing terms? Or did they predate that? (Can anything predate marketing?)

I’m always very happy to be critiqued! Thank you for doing that!

But I think I do more than just bring it back to comics.

But I do like comics:)

OK, from now on, let’s all assume genre is valid. Done and done!

But this post does more than that, I think?

I mean, can anyone name a great romance novel? Meaning, a real romance novel, with a Fabio cover, written by someone who’s subverting the system?

There’s gotta be someone out there, right?

Thanks for the feedback, Taylor! I really do appreciate it…

Adam

Exactly.

the sceptre of his desire

Specter?

I’m thinking of genre as having more to do with substance than with quality or target audience. ‘When did they start?’ could be considered seperately from ‘When did they become things so widely talked about that everybody could have an opinion?’ The latter is probably post-marketing, based on my sense of the term ‘marketing.’ (Of course, in a bit of fractalizing reasoning, we could ask the same two questions about marketing.) Main point is, I think a horror story was originally called that as a way of distinguishing the story from the norm. Why would they bother to put ‘A Tale of Horror’ if there was no norm? (Ah, but that might be marketing or, more specifically, advertising. So I must refer to the fact I used ‘mass marketing’ in the above and pretend like there is some threshold past which marketing-things become really shitty. Which there surely is.)

“OK, from now on, let’s all assume genre is valid.”

That would be great. But to be fair, this blog’s readers don’t seem to be genre lovers, so I can see why you keep making posts in this sentiment.

“I mean, can anyone name a great romance novel? Meaning, a real romance novel, with a Fabio cover, written by someone who’s subverting the system?”

I suppose people could but you’d have to be a heavy romance reader to be knowledgeable, and I’m not.

But look—I don’t know why a Fabio-style cover must be there to make it a “real romance novel.”

If you remove that weird bit of criteria, then sure, I can name some great romance novels: Gone with the Wind, Les Miserables (arguably not a romance novel but I think it is), most Jane Austen novels.

Twilight might go down as a classic in years to come (who knows), Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, that’s all I can think of on the spot.

But yeah…I don’t think you’ve thought this through very far.

the recipe of his dessert

“Therefore what people bemoan about ‘genre writing’ is its debasement, not its essence.”

When you try to clean up the woman you let her know you think she’s a whore. In any case, westerns predate mass markets, and, for that matter, modern romance predates Lawrence. I would say blaming this on capitalists is a stretch, and a delusion. The idea that the ‘essence’ of genres exists beyond tropes is odd, because the substance of genre, the materia of genre, is trope. All formulas, and all forms, can and have sustained immense artistry and sustained innovation, but they are neutral, empty vessels, which usually aren’t filled with much, and you don’t have to pretend there’s an ‘essence’ to them which is being polluted by other people who stand in the way of it being what it otherwise would have been.

Most people are perfectly happy with what their tropes give them, and always have been; they’re usually most angry at the people who, out of high-mindedness or (what’s worse) arrogance, refuse to give them to them.

If you equate ‘mass marketing’ with ‘capitalists’, you don’t get to tell me I’m delusional. One is an activity, one is people. Are free markets the only markets? ‘Private ownership’ is not dependant upon ‘strategies for commerce,’ is it? A socialist government could ‘market’ something to a ‘mass’ of people, couldn’t they? Besides which, I didn’t think I was ‘blaming’ anybody.

Yes, I feel as though this debate keeps coming up, and Mike M. and I must keep defending our position. Earlier today I was thinking, “Haven’t I already covered all of this?” But that’s the nature of blogging, and criticism, I realize. Just because I’ve written about something already—say, here—doesn’t mean it’s over and done with. So be it. (Though I apologize if it gets repetitive.)

I’ve thought a lot about romance novels, but this represents my first foray into actually writing about them. So, yeah, the thought can be thought a lot more thoroughly, I agree. And I agree there’s a real vagueness regarding the very term, “romance novel.” That stems from the fact that no one really ever wants to seem to talk about them. Well…let’s change that!

Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, definitely. I almost put them on my list above, but then decided I wanted to focus more on the 20th century. Because I feel it’s then that the form became debased—when it became dominated by Harlequin (which started in1949, I’ve since learned).

As for Fabio, I only mentioned him because—well, we can do this two ways, I think. One, we can sit around naming books that aren’t Harlequin novels but that are arguably romance novels. For instance, Michael Kelly’s Ulrich Haarbürste’s Novel of Roy Orbison in Clingifilm. That’s a brilliant little novel that revolves around the conceit that it’s first-person narrator, Ulrich Haarbürste, keeps finding excuses to exercise his fetish, which is wrapping Roy Orbison in cling-film. Did I mention that it’s brilliant? And obviously it’s some kind of romance writing, or even erotica. (For anyone curious, I reviewed it here, and you can read some excerpts here. And I can’t recommend it highly enough.)

But that only gets us so far. In some ways, that’s an exercise in redefining what we mean by the term “romance novel.” (Along those lines, Jean Genet wrote romance novels.) But what of the romance novels we all tend to think of when we hear the term “romance novel”—the kind of book bearing the cover I included at the top of this post?

As I mentioned in this comment, while I recognize that the vast majority of those books are churned out factory-style, I’m sure that someone is doing something subversive/artistic with them. Or, at the very least, that the potential exists. Because artistic potential always exists where there’s formula.

But, as you note, we’d have to be better versed in that aspect of this genre.

So I’m off, I suppose, to look for someone who’s doing research on Harlequin romance novels. I’m sure they’re out there…

… Thanks once again for all your contributions! I really appreciate having my thinking pushed…

Cheers,

Adam

*shrug*

Semantics it is. I didn’t call you delusional.

The pierce of his, uh, red sets…

Or: the precise, sore fetish…

Additionally, the ‘tropes’ to which I refer are more specific than those which form the basis of a genre’s identity. In other words, if you write I, Robot for the twentieth time, that’s what I’m talking about; not the simple act of including a robot or other imaginary technology. So we two are talking about different degrees of trope-itude. Yes, at heart, in their very essence, things must have something in common to be part of the same genre; this is different from a cynical rehash of a particular story or book.

You’re technically correct.

Well there must be some subversive, 20th century, romance authors who publish books with the factory style Fabio-esque cover art. That is a lot of criteria though! Good luck on your search!

His ‘defect’ is ‘horse-peter’.

His peter defies torches!

His peter iced, he’s softer.

So long as your opinion is that what you don’t like about genre fiction, in whatever degree of troping, is not part of the ‘essence’ of genre fiction, my point, whether it’s read or not, remains the same.

I feel cheated because I thought the writer was going to defend genre romance books.

She fetters his copiers.

But I am defending genre romance books! That’s precisely my point! (We just don’t think of the books I listed as belonging to that genre. Which is like when people say things like “Kurt Vonnegut wasn’t really a sci-fi writer,” or “Watchmen isn’t really a superhero comic.” How is Marguerite Duras’s Hiroshima Mon Amour not a genre romance novel? In other words, how is not in any way part of the romance genre? I’ll grant it’s an unusual romance novel, but it’s still working within the broad tradition of the romance..

But I suspect you mean, rather, that you’re disappointed that this isn’t a defense of Harlequin novels…? But this is also a defense of them—in the abstract, at least. See my comments throughout this thread. I don’t see why it’s impossible to write an excellent one of those. Sadly, I don’t know if anyone has done so (though I imagine someone has).

Cheers, Adam

Mind you, that’s not the only thing I’m looking for. I’m interested, rather, in defining romance more broadly, primarily such that it isn’t considered just a debased popular genre. It’s possible to re-view the genre much the same way folks have re-viewed sci-fi. Jack Vance, Kurt Vonnegut, Barry N. Malzberg, Angela Carter, Jonathan Lethem, Philip K. Dick, Ursula K. Le Guin—they’re all sci-fi authors. And that’s not considered odd. (OK, some prefer the term “speculative fiction,” but they’re all still sci-fi.)

So why aren’t, say, D. H. Lawrence, Marguerite Duras and Elfriede Jelinek considered romance authors? I consider them such. I want to consider them such.

Meanwhile, if someone is writing artistic/subversive Harlequin novels, I imagine that will eventually come to light. But it might take a long time. Look at how long it took folks to figure out that Patricia Highsmith was the shit.

No one thinks “Hiroshima Mon Amour” requires special defense on account of its being about a love affair. There is no controversy about the merits of the romance genre defined in the way you’re assuming it should be. So there’s either something wrong with your implied definition or you’re purporting to take a side in a argument that doesn’t exist.

I’m not here to propose a definition of the modern romance genre. But readers browsing in the romance section of the bookstore know what they’re looking for, and it isn’t the work of Marguerite Duras, and therefore if your definition encompasses the latter then it fails to capture a relevant cultural distinction.

Alan, your comment makes no sense.

Here’s my argument, represented in a more straightforward fashion:

1. Currently, readers have a very narrow definition of what constitutes the romance genre. They equate it with Harlequin novels.

2. I think that’s too narrow. It would be like equating the mystery genre with the Hardy Boys.

3. I want to redefine romance more broadly.

4. We should look to see what authors are engaging with the long tradition of romance writing. In other words, we should redefine our present understanding of the term.

5. I care fuck all about what Barnes & Noble files where.

6. What’s more, I wouldn’t be surprised if it someday turns out that someone writing those Harlequin novels is actually pretty good. Because formal constraints often breed creativity; see the Oulipo, and the CYOA example I gave elsewhere in this comments thread.

7. It’s going to be hard, though, to find that someone (assuming they exist) if the whole genre continues to be definied, a priori, as crap.

8. In this regard, the situation is akin to the state sci-fi. There’s a tendency to take the good practitioners in the field—your Angela Carters and your Jonathan Lethems—and claim they’re not really examples of the genre. And this dumbing down of the genre makes it take a lot longer to recognize that the supposedly “purer” practitioners—your Jack Vances and Barry N. Malzbergs—ever existed.

In other words, I’m proposing we change a prevailing cultural distinction. I think I’ve been pretty consistent on this throughout this whole thread?

Cheers, Adam

Adam, your idea that Marguerite Duras is to genre romance as Angela Carter is to sci-fi betrays an area of cultural illiteracy on your part. There is something that Barnes and Noble knows that you do not.

Alan, if you just want to hurl invective at me, by all means do so, but don’t expect me to respond. But I’d rather discuss and debate actual substance than not. So, along those lines, do you have actual specific arguments and points you want to make regarding any of this?

What is your definition of “the romance genre”? Why is my argument, my definition, inadequate? Am I wrong to argue that it’s a long literary tradition that includes works like the Arthurian romances, as well as much later works like D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and The Rainbow? Am I wrong to read Duras’s work as participating in that tradition?

Or am I wrong to assume that the romance genre includes contemporary works of erotica? In my experience, erotica is usually classified with romance lit, even when it’s most commercially defined; it’s usually even adjacent to the Harlequin section. And there are crossover works like 50 Shades of Grey. Are Duras novels like Hiroshima and Malady of Death and The Lover not engaging with a long literary tradition of the erotic, and its depiction in narrative and language? How about Elfriede Jelinek’s books, works like Lust, The Piano Teacher, Women as Lovers? I’m genuinely curious here to understand how I’m being so culturally illiterate. Why is Angela Carter sci-fi, and Duras and Jelinek not part of romance?

Or is there something to be gained by saying that romance is nothing but Harlequin novels? If so, what do we gain from that? Culturally and artistically?

Cheers,

Adam

How about Duras’s 1952 novel The Sailor from Gibraltar? Open Letter recently printed a translation. Here’s the copy from it:

“Disaffected, bored with his career at the French Colonial Ministry (where he has copied out birth and death certificates for eight years), and disgusted by a mistress whose vapid optimism arouses his most violent misogyny, the narrator of The Sailor from Gibraltar finds himself at the point of complete breakdown while vacationing in Florence. After leaving his mistress and the Ministry behind forever, he joins the crew of The Gibraltar, a yacht captained by Anna, a beautiful American in perpetual search of her sometime lover, a young man known only as the “Sailor from Gibraltar.” First published in 1952, this early novel of Duras’s—which was made into a film in 1967—shows those preoccupations which have so deeply concerned her in her later novels and film scripts: loneliness, boredom, the inevitability and intangibility of love. The lambent poetry of the book, and the limning of a woman’s mind, her love and sense of the inevitability of that love are singularly Marguerite Duras.”

Does that sound like something that has anything to do with the romance genre?

Here’s the film adaptation; the IMDb classifies it as a drama and a romance. There’s one external review for it, at The Auteurs. Here’s a paragraph from that review:

“[…] The Sailor is a slow, compelling and beautiful movie, which must have seemed unfashionably romantic when released in the age of free love – a tale of obsessions, in which a love affair takes on the qualities of myth.”

What’s more, Duras’s Wikipedia page says that Raymond Queneau criticized Duras’s earlier writings for their “romanticism.” (Note that the claim is not cited, and I can’t find a source for it.) Assuming the claim is true, was Queneau referring to novels like The Sailor from Gibraltar? I haven’t read it yet, but I tell you what—I’ll read it next month, over the break, and write a report on it here. (I’ll also keep looking for the actual source for this claim.)

Keep in mind that Harlequin Enterprises was founded in 1949. Duras started publishing in 1943. So what tradition was she working in, then, in her early novels? What tradition did her later, more experimental novels grow out of?

If you have a better account for this, I’d love to hear it. Whenever I find myself culturally illiterate, I like to better myself. Regards, A

What is gained by distinguishing genre romance novels as an identifiable category among works dealing with love or the erotic is that when you refer to the former people understand what you mean and vice versa.

Your sci-fi analogy was misleading in two ways. First, no one is surprised to find Angela Carter on the sci-fi shelves. Second, there is no stigma against fiction that deals with romantic love comparable to that against fiction that deals with the fantastic, rendering your defense of it unnecessary.

I hope it doesn’t hurt your feelings to point out another blindspot of yours: medieval romance and modern romance fiction have nothing in common but the word “romance.” You would be on safer ground relating Arthurian romance to science fiction.

No reply on the Arthurian thing?

So you don’t trust Barnes and Noble but IMDb is a good authority. Anyway, I thought we were talking about a literary genre.

Ok, maybe your brave defense of Duras would have been relevant in the early forties?

I’m not an anti-genre guy. I was just wondering if anti-genre guys were really just anti-boring-same-old-same-old guys. I can wonder about that and you can still be right about the fact that some people will still buy so-called ‘crap’ and like it. There is a difference between someone being passively unadventurous in their banal-but-enjoyable entertainment choices and someone who really believes it doesn’t get any better than what they already know.

I don’t think you’re an anti-genre guy, and I agree with you that most anti-genre is anti-boring, though since most all entertainment anti’s amount to just that I’m not sure that’s saying as much as it could. What I disagreed with was the historical-cultural argument you made as to why that boring exists, and, less significantly, the unintended condescension I perceived as implicit in that argument.

Looks to me like the ol’ Master of Desire there has used most of his point buy to focus on his strength, though, which means he had to ignore his other stats. If he’s increased his dexterity for AC—and, obvs, done what he can to have a fairly high charisma in order to be the “master of desire”—he can take hits to intelligence and wisdom without feeling much, but what about constitution? Depending on house ruling, the guy can only harvest so much from the two dump stats he has to play around with. If he’s dumped constitution, too, his hit points are pathetic, meaning he’s a total glass cannon. Which means if the two of them get attacked out there in the open field, he better hope its a solo monster of some sort so he can focus DPS, because mobs’ll just overwhelm him. Go nova, stay mobile—I’m guessing that’s not hampered terrain, but we may be missing heavier brush below the image’s frame—and hope that she’s a healer, because he is going to go down.

It’s not the shininess of the sword, but the stickiness of the tank, my friend.

Sure. As I said in the comment above, though, I worry he’s a total glass cannon.

+1

Next let’s find a Chris Higgs post about Oulipo and theorycraft the perfect whip-using, battlefield-controlling monk…

Alright, I can see that. What if I add: not everyone has the same awareness of historical context, therefore someone reading the 20th version of a classic story might not recognize the fact that it’s basically a redundant book (in the big scheme of things.) Some big-time lit-head does see this redundancy and as a result thinks less of the book’s author. He can even make public statements which unequivocally denounce the book as derivative and in no way progressive, nor retro in a way which makes the reader reevaluate the genre, or some other criticism. Does that make him a snob? Perhaps. Or perhaps it only makes him a snob if he’s a jerk about it. Regardless, should the author of this book hold immunity from comparisons to precedent? Based on your statements, which tout the innovation we may find even in well-established forms and tropes, I imagine you would say no. So if some critics have the general impression that the majority of genre writing is neither innovative nor re-imaginative, they could say ‘genre writing sucks’ and while it might actually represent their aggregate experience, and that experience might be more authoritative than that of someone who just reads whatever is on the shelf this week, it is perhaps too broad a statement to be taken very seriously. Do you agree?

It’s pretty clear that your ‘problem’ isn’t “cultural literacy” (‘culturacy’?), but rather, that you’re trying to change a definition that you do recognize as being normally held-to among the culturati but don’t see the compelling rationale for.

To the end of redefining “romance” broadly enough to mean something like ‘[all] narrative dominated by romantic love’, your analogy is fine.

(I don’t know Carter well enough to know that she’s a sci fi writer; let me substitute ‘fantasy’.)

“Carter : fantasy” counts on both Carter’s genre credential and the respect she gets as a good writer-whatever-the-genre; this unity is your target.

By saying “Duras : romance”, you advance your project of redefining ‘romance’ by a) naming an already-respected writer-whatever-the-genre, and b) putting that writer in the narrowly and derogatorily defined ‘romance’ genre.

As fantasy has come to be respected–or at least not automatically scorned by at least many readers of ‘literary fiction’–, it’s become normal to call a good writer a ‘fantasy’ writer and ‘fantasy’ a genre with good writing in it.

(Is fantasy less respected than sci fi because science is for whiz kids? Anyway.)

That is the normalization you’d like to see accomplished – or to deserve and get credit for accomplishing! fame! glory! – in the case of ‘romance’: it’s normal that a good writer be a ‘romance’ writer and normal that some ‘romance’ novels be good indeed.

If you were arguing that this normalcy already is the case with romance novels, then you’d be inculturate. You’re plainly arguing that it should be the case.

Although he misuses the tricky phrase “vice versa”, alan seems to have realized that you’re not being inculturate, but rather, are challenging culturacy. That is why he asks why you’d want to complicate things when culturate “people understand what you mean” and why he changes the subject inaccurately to incomparable stigmas.

“Meanwhile, if someone is writing artistic/subversive Harlequin

novels, I imagine that will eventually come to light. But it might take a long time. Look at how long it took folks to figure out that Patricia

Highsmith was the shit.”

Yeah, it often takes a while.

That’s pretty much what he did.

Maybe Danielle Steel? I think we’re over-analyzing. Certainly, some romance novelists will eventually get recognized artistically. I already listed a bunch but they got dismissed because they weren’t from the 20th century. Also, AD, it may be your perception that people automatically associate romance novels with Harlequin factory covers. When people mention romance novels, my thoughts don’t shoot straight to that. I think 50 Shades or Gone with the Wind or chick lit or…who knows…my immediate thought isn’t Harlequin novels with the cheesy covers.

I’ll reiterate though—Jane Austen wrote typical romance novels (regarding plot, anyway) and she is now recognized as one of the greats. To ascertain who the great modern romance novelists are would take people with much knowledge in this sector. Probably people who aren’t reading this discussion.

It’s a gassy cavil, but I’d like to see a thumbnail definition of “romance”. ‘Narrative or image oriented primarily by sexual love’ seems too general.

It’s true of Harlequin and of Georgette Heyer and the Regency… well, romance novels in her wake, but the sweaty straining in words both to make present the experience of sex and–unlike in what I’d call ‘erotica’–explicitly to make of sex something oriented to spiritual magnificence . . . there are those in Austen and Hemingway, but without the clammy prurience. –which combination of prurience and spiritual reach I’d call ‘generic’, generically ‘romance’.

(Have you tried reading Heyer? I think of her as a romance Agatha Christie. Also, as a bad writer.)

Is every story that’s a ratiocinatory adventure–that turns on the protagonist(s)/reader figuring out what’s going on–a piece of ‘detective fiction’? I know mystery/suspense/thriller books are made to be literarily less suspect by their having Oedipus the King and Hamlet in their genealogies… does that not seem my-dad-makes-as-much-money-as-your-dad to you?

I guess I respect it more when genre fans say ‘yeah–it’s not literary fiction–it’s just as good, so fuck off’. –the point being that “literature” isn’t even close to being coterminous with “literary fiction”.

Not really. In American publishing, “romance novel” has a specific meaning, and that meaning doesn’t cover any of the books mentioned here. Would you really call “Richard Yates” a romance novel?

I’ve never read it but even without reading it—no I wouldn’t

Alan, I agree with you.

This post does not make sense because it fails to defend the genre of romance. Instead, it lists a bunch of (already critically acclaimed) literary fiction and says – this is romance too! Expanding the definition of romance to include every book that deals with a romantic relationship makes a defense unnecessary. Is there anyone who is opposed to every book with a romantic relationship in it?

I used to work at a public library, and none of the books on your list are in the genre of romance. The romance genre is really and caters to lots of different tastes – NASCAR, Amish, paranormal, Christian, urban, viking, medieval, military, etc – but the books you list are established (critically acclaimed) literary fiction titles.

If you want to redefine ‘romance’ in a way that is totally at odds with how it’s understood by those who read and write in the genre, go right ahead, but I don’t understand the point. Totally redefining something is not a defense, quite the opposite…

Also, most of the romance genre is basically pornography. I don’t say that pejoratively, just as a description. (Anyone who’s ever worked in a library or bookstore knows the ‘women don’t consume pornography’ thing is an absolute lie and has always been a lie.)

Adam is not trying totally to redefine a genre. He is trying to show that the definiendum, the essence, already at work–that is, already being used as a pilot–when we say “romance novels” is also that essence in some writing called “literary fiction”.

He is saying that, if Harlequin romances are poorly written sensationalistic fare, then they’re poorly written sensationalistic examples of the species that includes Duras’, what, ‘relationship fiction’. –Duras’ novels which are therefore reasonably, if polemically, also to be called “romance novels”.

One of Adam’s points might be, then, to attack the scornful tribalism of “literary fiction” — eventually to question the priorities and values–the perspective–of the power accumulated and expressed in the knowledge that “romance novels” are generically, by definition, poorly written sensationalism.

A “defense” of Harlequin novels, or of Georgette Heyer, might be interesting, and might be what the title of this blogicle promises to some readers. A disappointment with the absence of such a “defense” is no great bar to understanding – if not to agreeing that it’s worth the trouble – the point of thinking out loud about a nearly uniformly derogatory and dismissive categorization.

http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/05/18/reviews/pynchon-luddite.html

Thinking about your post reminded me of this 1986 Pynchon essay, which converges on you here:

“The craze for Gothic fiction after ”The Castle of Otranto” was grounded, I suspect, in deep and religious yearnings for that earlier mythical time which had come to be known as the Age of Miracles. In ways more and less literal, folks in the 18th century believed that once upon a time all kinds of things had been possible which were no longer so. Giants, dragons, spells. The laws of nature had not been so strictly formulated back then. What had once been true working magic had, by the Age of Reason, degenerated into mere machinery. Blake’s dark Satanic mills represented an old magic that, like Satan, had fallen from grace. As religion was being more and more secularized into Deism and nonbelief, the abiding human hunger for evidence of God and afterlife, for salvation – bodily resurrection, if possible – remained. The Methodist movement and the American Great Awakening were only two sectors on a broad front of resistance to the Age of Reason, a front which included Radicalism and Freemasonry as well as Luddites and the Gothic novel. Each in its way expressed the same profound unwillingness to give up elements of faith, however ”irrational,” to an emerging technopolitical order that might or might not know what it was doing. ”Gothic” became code for ”medieval,” and that has remained code for ”miraculous,” on through Pre-Raphaelites, turn-of-the-century tarot cards, space opera in the pulps and the comics, down to ”Star Wars” and contemporary tales of sword and sorcery.

TO insist on the miraculous is to deny to the machine at least some of its claims on us, to assert the limited wish that living things, earthly and otherwise, may on occasion become Bad and Big enough to take part in transcendent doings. By this theory, for example, King Kong (?-1933) becomes your classic Luddite saint. The final dialogue in the movie, you recall, goes: ”Well, the airplanes got him.” ”No . . . it was Beauty killed the Beast.” In which again we encounter the same Snovian Disjunction, only different, between the human and the technological.

But if we do insist upon fictional violations of the laws of nature – of space, time, thermodynamics, and the big one, mortality itself – then we risk being judged by the literary mainstream as Insufficiently Serious. Being serious about these matters is one way that adults have traditionally defined themselves against the confidently immortal children they must deal with. Looking back on ”Frankenstein,” which she wrote when she was 19, Mary Shelley said, ”I have an affection for it, for it was the offspring of happy days, when death and grief were but words which found no true echo in my heart.” The Gothic attitude in general, because it used images of death and ghostly survival toward no more responsible end than special effects and cheap thrills, was judged not Serious enough and confined to its own part of town. It is not the only neighborhood in the great City of Literature so, let us say, closely defined. In westerns, the good people always win. In romance novels, love conquers all. In whodunitsses we know better. We say, ”But the world isn’t like that.” These genres, by insisting on what is contrary to fact, fail to be Serious enough, and so they get redlined under the label ”escapist fare.”

This is especially unfortunate in the case of science fiction, in which the decade after Hiroshima saw one of the most remarkable flowerings of literary talent and, quite often, genius, in our history. It was just as important as the Beat movement going on at the same time, certainly more important than mainstream fiction, which with only a few exceptions had been paralyzed by the political climate of the cold war and McCarthy years. Besides being a nearly ideal synthesis of the Two Cultures, science fiction also happens to have been one of the principal refuges, in our time, for those of Luddite persuasion.”

, but still merits a closer reading for, among other things, its prose and wiles.

I should point out that I don’t find this mode of inquiry very interesting. The question of whether or not there’s social or conversational injustice at work in the way ‘some’ nebulously defined group of people view ‘some’ nebulously defined group of books strikes me as at best intellectual indulgence.Your assertions took hold of me because they were attempting to articulate something about the nature of these things, but on the whole I have little to say here.

I can say that I take it as a given that any book in any tradition from any person has the same arbitrary potential of being worthwhile as the next one, and that people who think their clique is really where the cool kids are will never be right or convinced otherwise.

Part of the problem is that these guys don’t want what you’re selling–by which I don’t just mean the readers not wanting ‘literature’. I mean writers wanting to understand ‘precedent’, and I mean critics wanting to insignificantly modify their disdain to “‘most’ genre writing sucks”. The best we can say about most of the writers is that they want to titillate, captivate, and monetize, and if every once in a while a Ken Follet musters the cajones to put himself and the rest of us through a Pillars of the Earth, then god bless America.

It truly is something I should look into more thoroughly. Can anyone recommend a good history of literary genres? I looked up the term at the OED and found the following:

1b.spec. A particular style or category of works of art; esp. a type of literary work

characterized by a particular form, style, or purpose.

1770 C. Jenner Let. 5 May in D. Garrick Private Corr.

(1831) I. 384 With regard to the genre, I am of opinion that an English audience will not relish it so well as a more characteristic kind of comedy.

1790 A. Young Jrnl. 15 Jan. in Trav. France (1792) i. 273 It is

a genre little interesting, when the works of the great Italian artists are at hand.

1843 Thackeray Misc. Ess. (1885) 23 If..some of our newspapers are..inclined to treat for a story in this genre.

1856 ‘G. Eliot’ in Westm. Rev. Jan. 4 In every genre of writing it [sc. wit] preserves a man from sinking into the genre ennuyeux.

1880 S. Lanier Sci. Eng. Verse viii. 245 The prodigious wealth of our language in beautiful works of this genre.

1882 G. Saintsbury Short Hist. Fr. Lit. 50 A better notion of the genre may perhaps be obtained from a short view of the subjects of some of the principal of those Fabliaux whose subjects are capable of description.

1967 Radio Times 13 Apr. 10/5 Laike Moussike, the new genre which in the last eight years has given a new impetus..to Greek popular music.

…

Interestingly, that 1770 usage is the earliest record of the term in English, in any sense. (The other meanings of the word—1a. Kind; sort; style. and 2. A style of painting in which scenes and subjects of ordinary life are depicted—postdate it, originating in 1816 and 1849, respectively.)

I’m not sure I’d call it ‘injustice,’ but ignorance is ignorance. It might be perfectly alright to be ignorant about something which is ultimately unimportant; but a fact’s import doesn’t make one less-wrong to be wrong about it. If someone is wrong about something unimportant, I suppose that wrongness is also unimportant, unless it’s the result of a regular behavior or outlook rather than special circumstance.

I don’t know of such a history. Someone should write one!

I also take the ignorance as a given. Nor, for that matter, am I so willing to privilege the ignorance of the literary intelligentsia by aiming a unilateral critique of its self-interest. There is no conversation, no culture, which is any more or less self-involved, and I’ll know Adam doesn’t invest his own culture with undue authority when he doesn’t invest it with all of his idealism against ignorance.

I recently discovered that my two cousins–pretty regular girls, very nice, play lots of sports, etc.–really enjoy seedy, cheap romance novels and have this weird little clique of friends that reads them and passes them around and treats them as some special escape from their otherwise average lives. There isn’t really a point here but I will say that I loved hearing them talk about the books and it gave the genre an entirely different light as a result. Hearing DFW acknowledge Thomas Harris or James Ellroy has a similar effect, I think, not that these girls were touted literary geniuses, but they were discussing work that most people read on airplanes and then ignore as though it wasn’t something worth ignoring and it really seemed to matter to them. I can’t say I felt tempted to pick up the books or that I ever will but I can definitely understand this notion–in an increasingly less literary world, no less–of clinging desperately to those books you love with no justification or reason beyond the fact that you love them. Plus, I’d much rather hear some brilliant author discuss why they loved reading Psycho by Robert Bloch when they were twelve than hear them discuss Umberto Eco or some shit. Maybe I’m just not wired right.

I think you should check out the work of Tzvetan Todorov (Genres in Discourse, The Fantastic, The Poetics of Prose).

Actually, I think the fact that there is this long-standing “literary romance” tradition, with D. H. Lawrence, Jane Austen, and countless others, might be part of the reason why romance is off-limits in the “genre can be literature too” discussion. You don’t need to argue that a Haruki Murakami novel is literature even though it has a love story in it (and usually a really cheesy one at that) the same way you would have to argue that a Philip K. Dick novel is literature even though it involves robots. Romance novels are realistic like literary novels, and character-driven like literary novels. Their central feature, a man and a woman (usually) falling in love and experiencing some sort of happy ending, has been around in literary fiction from the start. The only thing that separates “genre” from “literary” romance, for the most part, is originality and quality (and I guess marketing).