There is no explicit meaning

From the NYT obituary of Osama bin Laden:

Yet it was the United States, Bin Laden insisted, that was guilty of a double standard.

“It wants to occupy our countries, steal our resources, impose agents on us to rule us and then wants us to agree to all this,” he told CNN in the 1997 interview. “If we refuse to do so, it says we are terrorists. When Palestinian children throw stones against the Israeli occupation, the U.S. says they are terrorists. Whereas when Israel bombed the United Nations building in Lebanon while it was full of children and women, the U.S. stopped any plan to condemn Israel. At the same time that they condemn any Muslim who calls for his rights, they receive the top official of the Irish Republican Army at the White House as a political leader. Wherever we look, we find the U.S. as the leader of terrorism and crime in the world.”

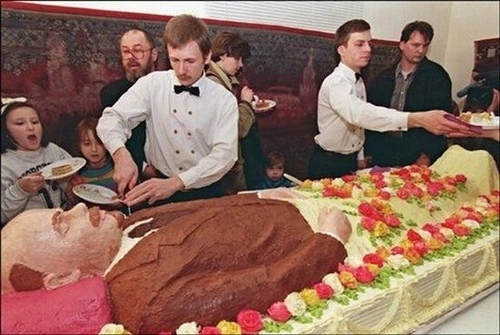

Words will always be words. I can call something whatever I want and it doesn’t mean a thing until it is validated by power (in whatever form) and then by people because of power. Everyone keeps “rejoicing” and the only people I see or hear questioning that celebration is the people. I’m sure it’s coming in small ways from the left but the President has not denounced it, let alone spoken to it so far as I have heard. If I remember correctly, people were pretty upset about this:

If you haven’t read it yet, Mike Meginnis wrote a great post on Kitsch and Bin Laden directly in the wake of the event. It comforted me, because I had just read and been thinking on Johannes Goransson’s (equally great) post on “Kitsch”. In his, Meginnis calls for kitsch as a way of healing the disconnect many of us feel in this situation. Kitsch can bring us together, he says. And I think he’s right, in one way. Unfortunately, none of this really changes anything. Like Wittgenstein’s theory of philosophy, everything is left exactly as it was. Exactly.

The explicit meaning of people waving little American flags is heartwarming togetherness.

The implicit meaning of people waving little American flags is someone handed those out.

The burial of the body at sea avoids the body itself becoming kitsch, as does “no image found”.

For some reason dictators really like publishing books. When Saddam was captured he was writing in a hole in the ground (dude I know the feeling). He published four romance novels and a number of poems in his lifetime under the pen-name “The Author” and was working right up until his execution. In the 70s Kim Jong-il published books on The Art of Cinema and The Art of Opera. Gaddafi wrote a book of short stories in addition to his Green Book, which can be read online; these are my favorite bits: “While it is democratically not permissible for an individual to own any information or publishing medium, all individuals have a natural right to self-expression by any means, even if such means were insane and meant to prove a person’s insanity” and its companion “Freedom of expression is the right of every natural person, even if a person chooses to behave irrationally to express his or her insanity.”

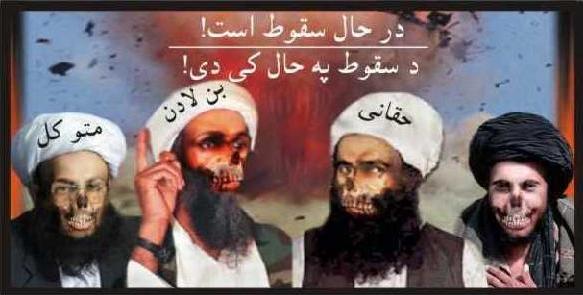

The style of propaganda leaflets distributed by PSYOPs seems purposely crude. Obviously very kitsch. As kitsch as commemorative plates with Obama’s face on them, for instance; imagine if they did that with a photo of Osama’s bullet-ridden head. These leaflets are made and dropped by the butt-load over provinces and townships, wherever we want to scare the crap out of people. If the United States is asked about these, they will always deny credit for obvious reasons: they look insane.

It’s not necessary to sympathize with Osama nor Obama to feel disgusted at the knee-jerk reaction of America’s corn-fed majority (sorry, but there really is fucking corn syrup in almost everything). I wholeheartedly disagree with violence as a means of conflict resolution, but I see where the dude was coming from, and I think that’s all he really wanted. Saying that Bin Laden “hated freedom” is like the Jerk when he thinks the madman “Hates these cans!” As with everything else, it’s a misunderstanding! America has always been unwilling to accept the fact that people hate us because we have done a lot of bad things. In The Fog of War, Robert McNamara says of WWII:

[Gen. Curtis] LeMay said, “If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.” And I think he’s right. He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral if his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?

But in speaking with most people about this, my mother for instance, it was expected that only two reactions were possible: joy or sorrow; one either rejoices at the spectacle or is deeply saddened by it. This reminds me of the blog Justin Taylor linked to a while back of “hot chicks” smiling at Ground Zero. Again, it is expected that there are only two options available. If, as Michael Moore suggests in Bowling for Columbine, we are informed by the examples our politicians set, it is unsurprising that the White House feeds into the dialectic as well (after all, what’s more dialectical than Democrats vs. Republicans, Asses vs. Elephants).

It seems like every time there is a situation on which the White House is expected to comment, they release a statement saying they are either “deeply saddened” or offer “congratulations” — neither of which carries any real meaning (as I always seem to tell my girlfriend, actions speak louder than words baby). As I Gchatted with my mother and thus was unable to show her with my face that I was conflicted, she was unable to understand how I could not be, as in the case of John McCain, “overjoyed” at the killing of such a bad man. I tried to explain that I was glad he was gone, but that the circumstances, and the reaction of our people and politicians, were in poor taste; to her, I was just being obtuse, yet again. There was a time when I thought I hated my mother. But I love my mom.

On Tuesday I unwittingly posted a quote I took from a friend’s Facebook page, the first part of which was not actually said by M.L.K. but by a young woman who had made her own statement followed by King’s more elaborate version of Ghandi’s “An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.” The fact that the misquote had spread like wildfire reminds me of how information works.

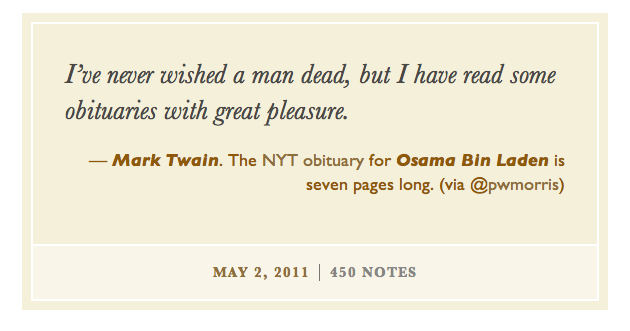

Once information is out in the world it is very difficult to stop. This is part of the idea of “journalistic integrity.” What that means in the age of the interwebs (when everyone can be a publisher) is sort of up for grabs. Right now there is a sort of battle to find all of these misquotes and correct them. The same thing happened with Mark Twain, who was misquoted as having said:

The misquote was picked up by Lapham’s, ABC World News, NPR, and others. When I say “picked up” of course what I mean is it was reblogged on tumblr. If I was embarrassed that I reblogged a Facebook quote without Googling it first because I recognized two out of three sentences (and I was), I cannot imagine how these guys must feel. Actually, I can; they probably feel like assholes.

There is a parallel, here, with the White House. Since the announcement of Osama bin Laden’s assassination there has been an absurd amount of misinformation. Finally, we were given the corrective statement that he was unarmed, with his wife who was shot in the leg as she charged the SEALs, and shot in the head. It is so much more than too little, too late. The problem is, most people grow disinterested after the first day of this news. I don’t blame them; it’s exhausting. So they got their information, which was that we shot the world’s most wanted man in the head because he went out guns blazing. These scenarios have very different meanings. If we can’t trust the information coming from the White House in one instance, why should we trust it in the next? And thus if we are not given photographic evidence of the dead body and the burial, why should we believe the DNA evidence? Seeing is, in fact, believing.

One of the epigraphs to Ben Marcus’s The Age of Wire and String is “Every word was once an animal. — Emerson” and I, like many others, thought this was rad as hell. I had never heard this quote before. Like my friend’s Facebook page, I trusted that Marcus was giving me correct information; I used it for the title to a blog post on this website. As with the King quote, one of our contributors (in this case, Chris Higgs) pointed me to an interview in which Marcus says that Emerson did not, in fact, say that; however, it was there, Marcus said, in the syntax of Emerson’s prose. In other words, Emerson may as well have said it, because he thought about things like that all the time.

One of the genius devices of David Markson’s This Is Not a Novel is the fact that he quotes a lot of people without using quotation marks. Some of these quotes are real and some of them are not. All of them are true; all of them are lies.

The point I’m trying to make is: it does not matter what is explicit about these misquotations or quotations because that’s not what we get from them; what we get is what we get from them: the implicit. In other words, we get the meaning that we give to them, in much the same way that John Lennon said, “…the love you get is equal to the love you give,” which he said while giving credit to McCartney for the song “The End,” the actual lines of which are “…the love you take/ Is equal to the love you make.”

In Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, hate and love are established as dialectics in parallel to a pair of quotes by Malcolm X and M.L.K. which end of the film:

I think there are plenty of good people in America, but there are also plenty of bad people in America and the bad ones are the ones who seem to have all the power and be in these positions to block things that you and I need. Because this is the situation, you and I have to preserve the right to do what is necessary to bring an end to that situation, and it doesn’t mean that I advocate violence, but at the same time I am not against using violence in self-defense. I don’t even call it violence when it’s self-defense, I call it intelligence.

— Malcolm X

Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding; it seeks to annihilate rather than to convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys a community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends by defeating itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers.

— Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The character Radio Raheem wears the words hate and love on his knuckles. (Spoiler alert!) He becomes a martyr at the hands of the police, which are of course the headless, militant strong-arm of all governments. Radio Raheem goes around blasting music from his boom box throughout the film.

Music is of course the output of the muse (according to the Greeks), which is connected to the general idea of God. This makes me think of the nature of God and the Devil, which most people like to think of as separate things; in fact, one of the earliest “proofs” against the existence of God rests on the shoulders of the dialectic. Epicurus (a Greek) asks, “Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?” The word for the latin Deus comes from the sanskrit Dev, which is indistinguishable from our word Devil. The word Lucifer means “bringer of light.” Light has and always will be equated with love and so, this is of course, incredibly confusing; and so, for obvious reasons, people would rather think of these as different things. But the truth is, every coin has two sides, but which is heads and tails? Hate is a confused, misplaced version of love. Both are part of passion, and you can’t have one without the other, which is exactly why they are the same thing.

In the film Old Joy, Will Oldham’s character says that a man came to him in a dream and said “Sorrow is simply worn-out joy.” The connection, which I think is implicitly, rather than explicitly stated in the film (although I cannot really remember) is that this is how the universe was created. Ghost particles, or neutrinos, are said to be the decaying energy that was created during the big bang. Without neutrinos we would not have the material world. This is very similar to the gnostic creation myth of the demiurge — the gnostics were one of the early Christian cults, before Paul went to Demascus (which is in Syria, by the by, where Sanskrit comes from) — wherein the demiurge spawns from the illicit love affair of a god and goddess; the demiurge creates the material world, which, according to the gnostics, is inherently evil.

Another dialectic is the nature of meaning. Meaning is split in two: explicit and implicit. Explicit meaning is when words are taken at face value, while implicit meaning is when we look beneath the words. In general, writers like to think about explicit meaning, while artists like to think about implicit meaning. However, as the title of this posts suggests, I feel that there is no real explicit meaning. The idea that words can be understood for exactly what they are is a fallacy on the scale of “In America we celebrate our differences.” There is no inherent, or explicit, meaning in anything; like love, everyone takes what they give.

The game Counter-Strike was (is?) extremely popular among teenagers (mostly dudes of course) in part because it feeds into this sort of dialectic. One is given the option to play as either the terrorists or counter-terrorists. What is interesting, however, is that, due to the fact everyone knows these faceless people playing as the terrorists are not evil, it is a game. If they have a microphone you get to hear them speak your language and you know that they are a person just like you. The whole thing works to diffuse the dialectic just as much as it does to establish and maintain it. What’s interesting, too, is that the teams do not look very different. The terrorists are not dressed in turbans or anything — they just look like soldiers or mercenaries — so that the implicit meaning of the game becomes: what is the differance? Of course, the game also leads a lot of people into believing that war is, like, really fun.

One of the things neoconservatives did so very well was to spread misinformation. This began when they were part of what was called “Team B” in the CIA (this is all documented in The Power of Nightmares, a BBC documentary which is available for free online). The documentary lays out the whole history of radical Islam and Neoconservatism, how they come from the same idea about the flaws of Western liberalism, and how their histories parallel and feed off of one another. The truth is, they can just as easily been seen as allies in the fight against liberalism as they can enemies in “the eternal battle of good and evil.”

The Egyptian who started what we now know as radical Islam, Sayyid Qutb, wrote novels, poetry, art criticism, and a 30-volume commentary on the Qur’an. He had been an outspoken critic of the West ever since studying at a Colorado community college in the 1950s, where he was horrified to experience his own personal version of Footloose (my theory is he was butt-hurt that none the girls wanted to dance with him), but it wasn’t until he suffered a heart attack under torture by the CIA (covered in animal fat, then attacked by dogs) that he began to equate the liberal attitudes he had seen in America with the savage brutality of our post-war foreign policy. Qutb characterized the United States as a culture obsessed with materialism and violence, an image we have upheld all too well. There is a very direct lineage between his ideas and those of Osama bin Laden, so it’s more than a little ironic that the neoconservative justification for the despicable torture at Abu Ghraib and other secret facilites (now strengthened, apparently by the fact we “got our man” because of it) was that we had to do so in order to gather information, in order to get those responsible for terrorist attacks (if that’s not clear enough, it’s ironic because the terrorist attacks started with torture and continue because of toture).

Many people don’t know or care what our soldiers do in Iraq and Afghanistan so I will tell you some things that are well-documented by people who do care (if you already know, good for you). Much of what our soldiers do is they gather intelligence by raiding homes, sometimes at random, making a whole lot of noise and chaos, then they arrest (in many cases) all the men in the home. They band the men’s wrists with zip ties and cover the heads with hoods, then the men are taken away without being charged with a crime; their families are not often told where they are going or when or if they will return. It’s estimated that 70-90 percent of these detainees are innocent. The military has a pathetic few translators and so much of the time the families are spoken to in English, a language they don’t understand. It’s a confusing, terrifying process. This is considered shameful in Middle Eastern culture (and let’s face it, anyone would be pissed), and so the honorable thing to do is to kill as many American soldiers as one can: this is where the insurgency comes from (to which our military is counter-) and this is why it seemingly has no end; it is a cycle.

I’m not saying there’s an easy solution to this, in the same way I would never suggest that forgiveness is easy. The hardest thing to do in a conflict is to look at yourself as the cause, much easier to place blame than to accept it. It’s the ego that gets in the way. I am consistently amazed by second-graders’ ability to solve conflicts because they can look outside the situation and into their own fault — most adults can’t do this, which is why people hire marriage counselors — but once these kids develop egos, it becomes very difficult to reason with them; they become brats. America is a brat, basically, with an epic ego.

I recently had the great pleasure of asking Pierre Guyotat if he felt that we needed to see “the image” (photos of Osama’s lifeless corpse with a gaping bullet hole above his left eye, the body being scrubbed and dumped into the ocean). His answer was “Bien sur” which was translated as “Of course.” Of course, bien sur does not really mean “of course,” it means something more like “I’m very sure.” At dinner his translator Noara Wedell told me, on the art of translation, that she believed there were as many languages as there are people to speak them, and that every communication between different individuals was its own unique tongue. In other words, there are so many factors that go into making sense of language, such as social background, political ideology, geographic roots, dialect, etc., that it is impossible to say that any of us speak the same language. For this reason, texts in translation will always be whatever they are for whoever reads them, but this is no different than what they were in the original language. This doesn’t mean, of course, that we shouldn’t try to be clear in what we say and how we say it, but we should at least recognize that, like all writing and art, it is folly to expect to be understood for what was meant to be said.

The same can be said of images. If an image says a thousand words, those thousand words are exponentially exacerbated by the fact the words will be interpreted in various ways by however many eyes in which the image is conjured. This is exactly why the Obama administration does not want to release them; they’ve apparently learned the lesson of Abu Ghraib. Everyone knew what was going on there, but the pictures made it real — it also made it confusing. An image is like a prism for meaning. One of the ideas of literature is to conjure images in the mind of the reader, to cast them on the wall of one’s mind’s cave. But let’s say I say something like, “The sky is blue.” Seems simple enough, but what blue? There are as many blues as there are eyes for seeing, and in fact many more than that. As Josef Albers points out in The Interaction of Color, colors also change depending on their context. Say we take the same exact color blue and place it atop a background of yellow, pink, or orange. We will see the same color blue as different shades because that is how color works, and that’s how language works, as well. In this case the truth is there is no blue, no yellow, no pink nor orange. There is only light and your eye and the color you see is the length of the wave in relation to other waves. There is no color, except in your mind. The reason people can go for so long without knowing they are color blind is that there is also no black and white, but an infinite number of shades of gray (this is a slight exaggeration). If truth and love are light, darkness is less a lack, and more a different way of seeing. As Maggie Nelson says in Bluets, The sky is blue because space is so black.

In 2001, Karlheinz Stockhausen caused a shitstorm when he said that September 11th was “the greatest work of art ever.” What he meant, I think, is that it was a mass spectacle orchestrated by individuals, meant to convey a message, on the grandest scale of all time. Unfortunately his comments were, in the greatest sense, “too soon” and also unnecessary, because the message is there to be had by anyone. Stockhausen was always controversial because he had a habit of privileging some humans over others. He very much thought that we were not created equal, and he seemed to have lost faith in the ability of people to learn. At his reading Guyotat said that he hoped what his writing could do was to give people faith that they too can think.

I have a theory that writers are a little like dictators and artists are a little like terrorists; this itself is a dialectic, but what I mean is, writers really want to control people and lead them to an idea, whereas artists want to create a spectacle. The terms are not mutually exclusive — like I said before, there are no dialectics and there is no explicit meaning — teardrops don’t flow two ways, but as many as the paths across one’s skin allow (as in Jeff Goldblum running his hand over Sam Neill’s wife’s hand in Jurassic Park). Plus, they all splash eventually. When asked if he felt art was a crime, Stockhausen replied with a muddled response that the audience did not buy tickets to the concert. His remarks were crude and insensitive, but so is American black propaganda. His ideas of intelligence are exclusionary and elitist, but so is our intelligence community. I think his answer to this question from a 1972 lecture, regarding the nature of dehumanization in electronic music (of which Stockhausen was a pioneer) speaks volumes of what he meant:

Tags: colors, confusion, counter-strike, dialectics, evolution, good vs. evil, images, in other words, meaning, of course, paraphrasing like a motherfucker, power, understanding

Wow, this is one heck of a post, Reynard!

What gives me the most pause is….you had dinner with Pierre Guyotat!!!

Oh, man. I would love to hear more about that.

that was…wonderful.

thanks for this!

thank you all for reading and watching

a really well done piece of propaganda, seriously, it’s only borderline delusional and zips to utopia only once or twice like a damp bottle rocket or reminiscing drunk, I gotta utopian dream that Kirsten Dunst is my girlfriend, but implementation is everything, so, there is this chasm and I am a civilian, it appears both you and that stoner Stockhausen have the mentality to order executions, that your poor mama has a lad with such bottomless confusion, and news flash god is a moot point because of free will

read this and felt interested

Not bad, not bad. It’s a long climb out of the monster’s dream…

lol

corn starch or corn syrup

what the sam hell

can’t get anything pabst you can i, i edited it because i’m not a journalist but i guess this is my retraction, thank you for pointing it out

this post is stunning. i’m glad i finally took the time to read it. thanks.

Exactly, like the way Bush kept referring to the 9/11 hijackers as “cowards.” Cowards? Really?

It’s so interesting to me that you differentiate between literary artists and visual artists. I usually think of us as pretty similar.

i thought it was interesting that guyotat, when asked if he thought his novel eden eden eden being banned in france was a good thing, he said no because it made it an object

that’s interesting to me. did he mention anything about the actual nature of ‘reading’ texts like eden eden eden? it almost functions more as something conceptual for me than a novel, due to its seeming resistance to narrative tropes (i’ve been reading it on and off for over a year and i’m still not done with it).

no but you should ask him mike!

Great post, Reynard.

Great post, Reynard.

meandering, desultory, not all that insightful or scathing.. i couldn’t finish it.

i know dude! i was gonna be all tl;dr but you said it man, you said it, desultory was my word of the day the other day so it must be kismet to see your faceless ass all up in this dude’s grill, i love it when people tell me they couldn’t finish finnegan’s wake but that it was totes cray cray, makes me all teary eyed and such like i’m cuttin onions with my fingernails all grown out like switchblades on lock

i feel good that i raged jim chen