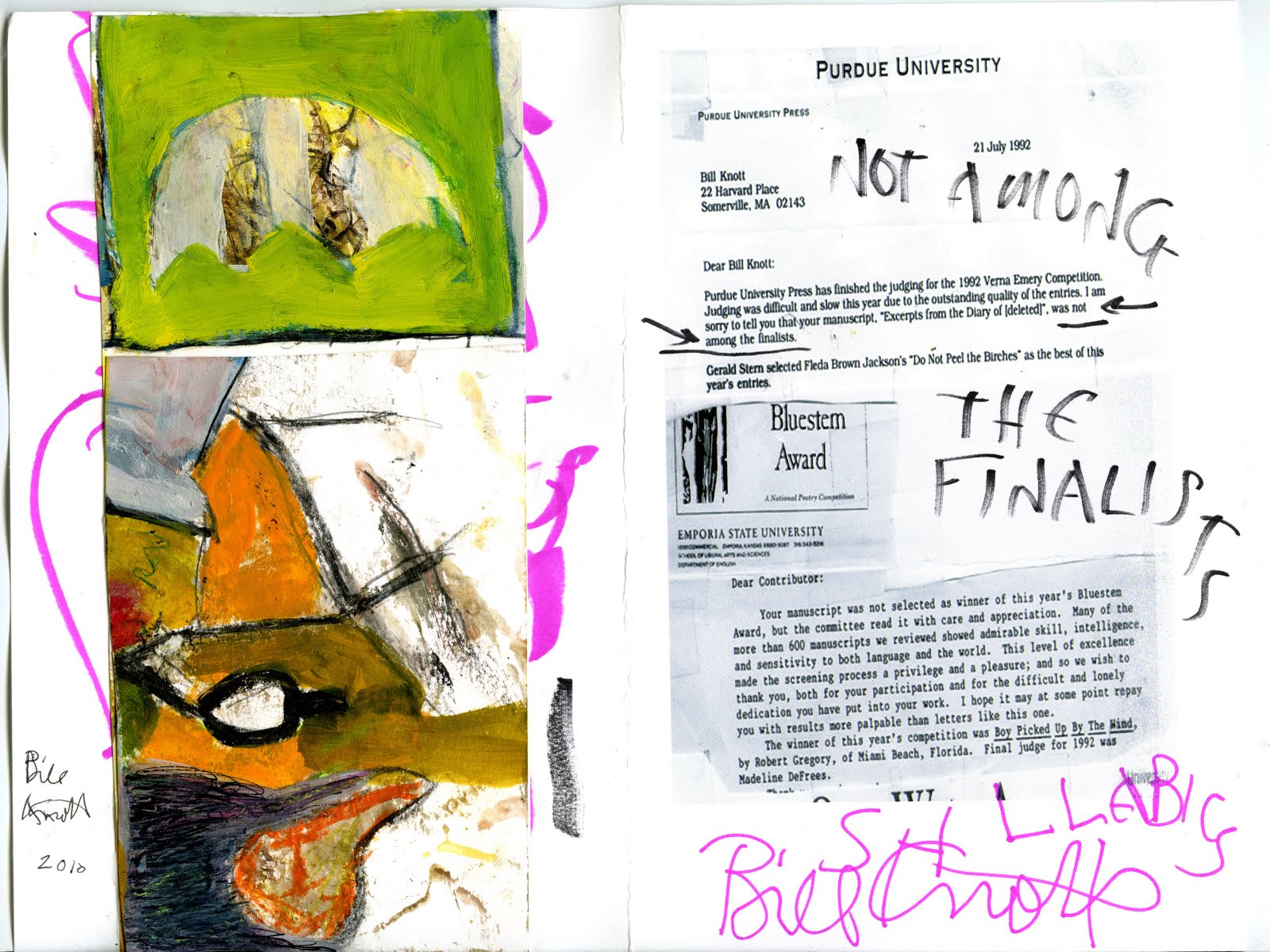

Bill Knott Week Begins Today

Bill Knott, born in 1940, is a vital and idiosyncratic force in American poetry. His first book of poems, The Naomi Poems: Corpse and Beans, was published in 1968 under the fictitious persona of Saint Geraud, a poet who had supposedly committed suicide two years earlier. His subsequent books have appeared under the imprint of presses large, medium, and small, from FSG to Random House to the University of Iowa Press to Salt Mound Press. Many of his books and chapbooks, especially in the last twenty years, have been self-published, or, more recently, made available for free electronic download at Lulu.com, a situation Knott half-balefully and half-gleefully describes as “vanity publishing” in interviews and on the blogspot blogs he carefully maintains.

I first became acquainted with Knott’s work during a 25-city READ MORE >

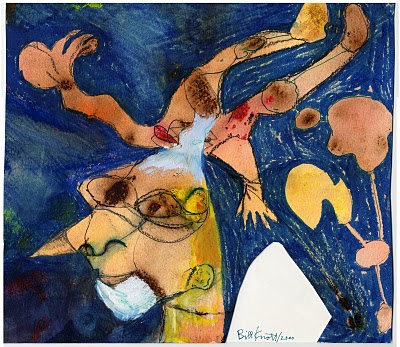

Bill Knott Week Notice

The Week of May 2, HTMLGiant will be running a series of posts about the poetry and person of Bill Knott (he who painted what you see below.) If you would like to contribute an anecdote, some words about a favorite poem, an appreciation of a particular aspect of Knott’s work, a story about Knott as a teacher or public person, or any other Knott-related thing, please email your submission to: kyle (at) kyleminor.com

Open Letter to Bill Knott

Dear Bill Knott,

I love the free PDF books of your poetry. I have greedily downloaded them, even though I also have copies of your more traditionally published books. I’m writing to let you know that it would be really easy to make these already free books available for wider free dissemination on ebook readers including the Kindle, Nook, and SonyReader. Although there are sophisticated softwares that would make possible extravagant multi-platform releases, the easiest thing to do would be to make the poems available as .txt files in addition to the PDF’s you already share so freely. I ask because I would like to carry your poems with me everywhere I go. Probably I am not the only person who has this desire, but probably other people are too intimidated to ask, for fear that the request will be met with an entertainingly self-deprecating response on your blog. So I also ask on behalf of the others.

Your small but rabid readership awaits your next gesture of charity. Also, if you choose to make these files available, I will link them prominently here on HTMLGiant, and you will have an instant readership of 100-1000 new readers (estimated), many of whom will be encountering your poetry for the first time. Happily, would be my guess. Also, given the reprobate nature of our readership, many of those readers would likely send copies of the poems to friends without sending you a cent. I would imagine that this imposition of piracy and victimhood might also appeal to you. If you chose to receive it as a gift, I would request a reciprocal gift of more visual art, some of which I would promise to display prominently on the site in celebration of your work and in lament of your frequent dismissal of it, which may be sincere, but which is anyway wrongheaded, since you are one of the most important poets of my reading life.

Sincerely,

Kyle Minor

Reader

Toledo, Ohio

Lotsa Action

HEY, there’s a new jubilat website! Heather Christle tricked it out with all kinds of good, including stuff from the archives, an A/V closet, and a wack index.

Excellent Dark Sky Magazine is doing a give for the excellent Brian Allen Carr’s excellent Short Bus. Yarta goget tha buk. On the now.

At Full Stop, David Backer points to Buzz Mauro’s Everyday Genius story and says that “dressed up with a few offhand observations, whimsical musings and flourishes of free association, ‘Delicious Noodles’ asserts itself as a convincing self-contained whole.” Then Backer points to a story by Matt Bell, from Conjunctions, that I overheard Matt talking about in a bar in DC on Saturday. “You’re supposed to do whatever you want with it,” he said (paraphrase).

Gabe Durham’s Fun Camp book will be out from Mud Luscious in 2013. If you’re an online literature reader, you’ve probably seen a piece from this here or there cuz they been everywhere man.

Also in new books: Publishers Weekly announces Melissa Broder’s Meat Heart, forthcoming from PGP in February. Also in PGP: Chris Toll’s The Disinformation Phase is now available for pre-order.

Also also: congratulations to Stephanie Barber, announced yesterday as a finalist for the Sondheim Prize.

At Tyrant Books, pre-orders are open for Michael Kimball’s renewed novel, Us, too.

And Dzanc just nabbed three by Stephen Graham Jones.

I feel like these roundups are of limited value. Is anyone still with me? There’s more goodness.

Like life. Ariana Reines remembers Paul Violi in a personal post that really blew me away.

If you’re not reading Bill Knott’s cranky blog, you don’t know what the Internet is.

What is the poetic equivalent of this throw from SS (Alexi Casilla, 4/18/11)? In what journal would it appear?

4 Things

Bill Knott will dedicate a book as you (yes, you) please.

Ryan Call and Christy Call’s 2008 story, Pocketfinger, at Everyday Genius.

NYTimes 100 Notable Books of 2010. I’m not on there. Are you?

What, a NOÖ Journal? Yep, great poems, great reviews, great stories and this WHAT WAIT A SECOND comic from John Dermot Woods (from which I clipped this roundup’s leading image).

Criticizing Criticism: Matthew Zapruder suggests you SHOW YOUR WORK!

Matthew Zapruder in action.

A few days ago, the Poetry Foundation published “Show Your Work!” an essay by Matthew Zapruder, in which he calls for a sort of renewal of the spirit of poetry criticism. You should read the whole piece for yourself, but here’s the part that I take to be his thesis:

Critics can do one of at least two things. The first is simply to insist that something is good, or bad, and rely on the force of personality or reputation to convince people. The second is to write, with focus and clarity, about how the piece of art works, what choices the artist has made, and how that might affect a reader. Only then can the reader grow to meet work that is unfamiliar, that he or she does not yet have the capacity to love.

In short- Yes, absolutely. For more, flip to page A16.

March 31st, 2009 / 10:31 am

A Review of Nick Sturm’s How We Light

How We Light

How We Light

by Nick Sturm

H_NGM_N BKS, June 2013

104 pages / $14.95 Buy from Amazon or H_NGM_N

“One traverses the same paths of thought as before. Only they seem strewn with roses.”

– Walter Benjamin

A question I’ve learned to ask my students this semester is, “What did this book of poetry make your body do?” I ask this 1) because it’s a question that has nothing to do with proving that you understood a book and everything to do with articulating an experience you had with a book 2) because it steers students away from focusing on “disliking” and “liking” and steers them more into intuitive, momentous ways of thinking that help us get unstuck / stuck into more complicated ball pits like: Did the lemonade in this book (“I drink lemonade and migrate into a system of becoming” – “I Feel Yes”) taste like it was made from concentrate or by hand? How does the repetitive presence of lemonade twist and gut the aphorism, “When Life Gives You Lemons, Make Lemonade?” Can a sour nest of pressed pulp devolving into a drink that tentacles us to words like brightness, warmth, shine be considered a kind of (un)holy transformation? Is that what your throat’s Charley Horse is telling you? 3) if students don’t learn that poems should do more than sit on a page, if students don’t learn that NOT feeling something grip or rip you is an indication that something is wrong, then I don’t know what we are using these institutions of higher yearning for.

Q: What did How We Light make your body do?

A: Bargemusic

It’s a question that’s not easy for students to answer, mostly because they are not used to incorporating their sensory organs into their thinking. They are often overwhelmed by the idea of paying attention to those reactions, by taking cell inflammation and disruption seriously, by collaging it with the logical systems of reading comprehension that are pressed and pressed into them. Lisa Robertson says a simple thing in her essay, “Time in the Codex,” from the book, Nilling, “I feel astonished that any institution could have placed [a book] in my hands, then left me alone with it. Reading misuses privileges, abuses authorities, demands interference.” Is reading and experiencing reading always volatile? I think the answer might be Yes in a way that makes me consider whether or not volatile-ness is inherently violent or violence making, whether interference is inherently violent or violence making. I forget that power is not only a thing that is stolen or improperly kept. In Robertson’s insistence and word choice, there is a leaning into the ways in which the existence of the book and our ability to digest it defies the way transformation and permission is distributed. Free Pattern Tune-Ups. Free Limb Loosening. Free Energy Glisten. A different kind of Universal Health Care. Will you open yourself up? Will you receive these things? It occurs to me that I don’t register enough how INDULGENT the act of reading is. It occurs to me that this quote is making me re-define these words, volatile, indulgent, in charged ways that I wasn’t planning on. I am beginning to associate them more thickly with pleasure and the detection of shifts. But then again, I read because reading is always interfering with the rituals I use to create expectations. It is always updating my machines. Reading is the experience of inhaling process and practice and building and force without expecting to feel recognition, nodding, without expecting to feel that what we glimpsed was completely representable. Bruce Andrews on Gertrude Stein: “Here, the meanings we construct are not compensatory. Readers don’t perform some co-invocation of a lost or ever-receding presence. This isn’t reading as containment, or rollback, but as extension.” I dream about bridges. I dream about the possessiveness reading abandons. I dream about soft gauze killing my boundary waters. Sometimes I make a sandwich and watch everything do more than I could imagine. (“Beautiful beautiful Animal / animal” -Upstairs With His Sandwich) Ben Mirov says, “Just as artists and writers have imagined sentient machines in their work, so too is it possible to imagine a poem that is imbued with qualities beyond the structure of its coherent materials.” Poor statues. They don’t move. They don’t grow kites out of a shoulder.

Q: What did How We Light make your body do?

A: “A man who doesn’t love easily, loves too much.”

– Special Agent Dale Cooper

I am not a person who comes easily to joy. Or rather, I feel joy constantly. There are dead leaves outside right now that smell like parts of the earth I’ve never seen. I walk to school everyday for the first time in years and listen to these songs that cover my organs in gold paper so hard I have lay down in the wilds. But it also hurts. It feels turbulent! The intensity of it, the impact of radical immediacy, how it seems tied also to my ability to feel immensely dented by you and everything else touching me. Can I survive it? I’m not convinced How We Light is a book that comes easily to joy, either, though it is often the first thing one can and should note about Sturm’s poetry, about where his poetical contraptions get their antifreeze. The texture of How We Light’s exuberance is pulpy, palpable, pulse-ridden.

“Why something in a word out of its body

makes me feel everywhere as air, air that lives

in mouths and birds all peach pie and dynamite”

– I Feel Yes

You know what chainsaws actually are? They are exclamation points. Boorish and toothy hounds. “My actions are excessive!” -I Feel Yes. You know what exclamation points are? Exclamation points are mouths that can’t help themselves, that can’t help interfering with the steady speed limit of a page. They are the inevitable slobber marks of awe force making you and the text slippery. They litter the fourteen pages of dawn and rumble that “I Feel Yes” is, one of two long poems that appear in How We Light. These moments of exclamation / proclamation / declaration aren’t enacting a refusal to be left out, though. They aren’t a power grab. Their presence isn’t one that feels aggressive or forceful here or in one of the titles which repeats nine times throughout the book, “What a Tremendous Time We’re Having!” They aren’t demanding attention in that way, which is exactly why I am drawn to them, why I’m whelping for them in this book’s terrarium, underlining away. They are, like lemonade, pure-ish in the mane and straightforward. “O human trying! O American bison!”- I Feel Yes

A Still From Doug Aitken’s Migration

What’s different, inside the frame of “I Feel Yes” and the book, is that these moments of joy, of piercing through, aren’t privileged. They aren’t positioned to make the reader look at and admire them for their unbridled side heaving or for their half court language shots. In the other long poem, “How We Light,” and in many of the other poems in the book, punctuation is removed, floating all seismic activity and feeling together into an enjambed collectivity (co-trembling). This is a whole body accounted for and throwing waves at and through itself.

“When I speak it is the opposite of bones

Real life bones, my name on my hands.

I understand now, the valley full of brains.

Let’s have a conversation using only our skin.”

– “I Feel Yes”

December 13th, 2013 / 11:05 am

Thomas Patrick Levy Excerpt

from I Don’t Mind if You’re Feeling Alone

Have you lacked power?

When you were in the mall, I was drunk, looking for the toilet, photocopies following me everywhere. When you were brushing my teeth, I was in the Oldsmobile, the cold water flushed over my face like a flash of light in the woods.

I could see you there, watching me with your ugly lens, my body bent into the ice chest like a baseball bat. The baseball bat wrapped out of a tree into the angles of my body.

At 4 am we’re crossing the street as if it were a river. Your eyes watching me like the eyes of a water beetle. I turn around twice, tabs of mint against my cheek.

I tell you how precise I am. I touch the neck of the steering column. I laugh to myself, folded like a gerbil. I touch your thigh which trembles with your bones. I’m trying to sand this down, dropping each telescope into a glass, carrying a small bag between my fingertips.

Did you ever wonder if you were crazy?

I walked and walked to understand blood oranges and avocados. I walked until perhaps I thought to keep walking north until I became a mountain. And when I became a mountain you looked at me in the morning, I was obscured by clouds, but you saw me beautifully—my new hair style, a pair of pants, my tie perfectly knotted.

Did this seem normal?

Feels like a film. Mostly rock stars, stairs, boots, coats. Shadows covering the street. Cold like a walk-in. I am saving the milk, breaking a box apart. Smiling at you. A leather strap across your chest, a melon beneath your arm.

Have you experienced any cravings?

Once, I’m like a twenty-dollar bill. I can’t find you anywhere. I go around and around. At the store I see a girl with striped arms looking into the glass at a bottle of seltzer. I go back to your house and find her drinking alone. You’re there too, smoking, staring through a kind of enlightenment, looking like a peachy finger, brush strokes of smoke crushed against your forehead.

What is an allergy?

Or once, I am in your car driving through the woods, hot air kicking in at us through the windows, we have dust in our mouths, I cannot see but watch the ghosts jogging on the roadside.

Your lover turns to me, her hair like the discarded shell of snake skin, and she tells me that I am small, that I am inside her box.

I close my eyes and watch soccer players silhouetted against a wall. I feel like a rapist. Maybe my throat closes up and I can’t breathe, maybe my heart rate increases, maybe I see the morning in her chest, coming at me like headlights through the trees.

Are you convinced that your life can hardly be successful?

Please understand, I tried to find the perfect place to sit.

I didn’t know what to do with my hands. I sat on the floor, folded back the cover of a coloring book. Your tongue came later, after it was in Charlie’s mouth, after it licked the gummy insides of a shot glass.

I still worry about my breath.

I sat under the pool table, then on a rock in the yard. You might have found me like that, your hands running across my shoulders and down my thighs while I thought of my grandmother with her hands of crucifix wood.

Later, with the crucifix in my mind, I would remember that I was wearing fishnets and high heels, that you were moving not like a whore but like a drapery. I buried myself in you, a game of hide and seek.

I went upstairs to sit in the folding chair, tried the recliner, walked home, frustrated.

I furiously wiped the surfaces in our kitchen. You came home late and found me strangling around the apartment like a weed, a muted cooking show on the television.

Are you on your way?

It was late. You had spent all day like this. I cut a lemon, put it down the drain. I wanted to break you like an axle. I went outside, drove my fingers through the bark of a tree as if my eyes were made of trees.

I thought you only cry at night. I felt like breath, I took off my sunglasses. I thought you will never change and drove into the mountain hoping for a truck to come between us.

Do you understand that self-knowledge is insufficient?

I was worried I wouldn’t wake before the fish started swimming. We had been around your yard all night, started in the grass and went through the cellar door as we began to hear them waking.

One day, you said, the fungus just started going away at your brain, saw them coming up from the ground each week, watched the gardeners hack them down.

One day, with your eyes flushed like the burn of a cigarette, you said you woke and couldn’t get your feet down on the world.

They came down later and called us fucking freaks.

I was on the couch in a trench coat, my heavy boots dug into the cushions. I rocked back a little bit, thought about walking outside across the street, into the stream near the train tracks, into their pink sky.

A native of New Jersey, Thomas Patrick Levy now resides in Southern California. His work has appeared widely across the internet and in select print journals. For more information visit him at www.enumerations.org.