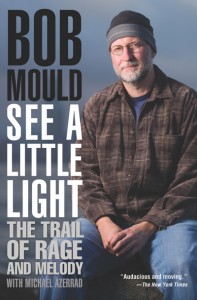

See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

by Bob Mould with Michael Azerrad

Little, Brown and Company, June 2011

416 pages / $24.99 Buy from Amazon

Why would anyone expect the ex-member of a famous rock band—those fertile dens of back-stabbing, girlfriend stealing, passive-aggressiveness and all around hurt feelings—to offer a healthy recounting of his time in said band? It’s like asking a combat veteran to empathize with the people who shot at him.

Yet, for those rock artists we truly admire, we crave that kind retelling. They’ve blown our minds so many times in the past with their transcendent work. If we’re disappointed they can’t deal with their issues enough to tell their band’s story in a fully-realized way, it’s only because we’ve learned to expect that much from them.

I skipped reading Bob Mould’s autobiography See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody (Little, Brown) after hearing Mould was less than resolved about his time in the formative post punk band Hüsker Dü, and in particular with his relationship with drummer/songwriter Grant Hart. I was a big Hüsker fan in the eighties and nineties, and I’d identified closely with Mould’s rage on classic albums like Flip Your Wig, Zen Arcade and Warehouse: Songs and Stories. I’d fallen away from his work around the time of his last album as the frontman of the band Sugar, and steadily found myself less interested in him as the years passed. The singer was so associated with the blood-curdling screams he’d let loose during his Hüsker years, I preferred to think of him as conquering his fury, moving on to better things, getting over it. Yet here was Mould, supposedly getting thorny about Hart and bassist Greg Norton in book form. Not interested.

But those who skip See a Little Light for these reasons will miss much of a story that few but Mould can tell: of Hüsker’s beginnings and ascendency, of the nascent eighties hardcore subculture in America that would lay the groundwork for the massive grunge movement in the nineties, not to mention refreshingly candid insights into Mould himself, one of his generation’s most conflicted icons.

Mould didn’t get riddled with rage by happenstance. His upbringing in rural upstate New York with an alcoholic, abusive father was plenty turbulent, and discovering his homosexuality in adolescence only further alienated him from those he grew up with. Most harrowing to me was when Mould was eighteen and for the first time away at college in St. Paul, Minnesota, trying to find his place in a confusing world. Not only were they stringing up homosexuals like deer back in his hometown, but, Mould writes, “the weekly phone calls with my family were difficult enough, especially the ones where my father threatened to sever my financial support or escalate his violence toward my mother.” I can only imagine a young, scared Mould desperately needing to make urban Minnesota work for him, knowing he had no home to go back to.

Green Lights

Green Lights

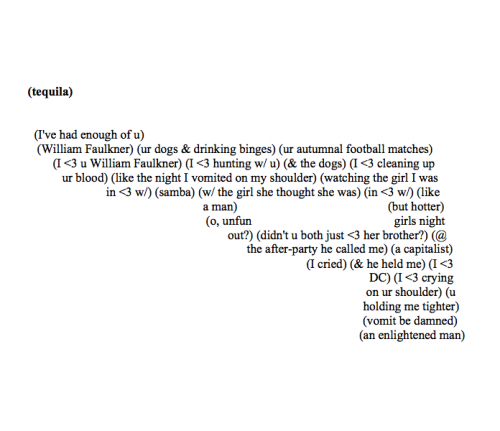

Contrapposto Action Queen

Contrapposto Action Queen Eternity by the Stars: An Astronomical Hypothesis

Eternity by the Stars: An Astronomical Hypothesis