How to Be a Critic

At the risk of greatly oversimplifying matters, if you want to be a critic, you have two options: to proceed either in good faith or in bad. Both approaches have their limitations.

How To Be A Critic (pt. 4)

Resist making value judgments.

How To Be A Critic (pt. 3)

The Lowest-Grossing Movies of 2011

As I’ve been suggesting in my past two posts (“How Many Movies Are There?” and “How Many Movies Have You Seen?“), regardless of how one defines the parameters of a feature film—let alone a movie—there are far too many of them for anyone to watch. The IMDb lists 8143 titles in their list “Feature Films Released in 2011“; assuming they’re all at least 40 minutes long, that’s a combined run time well in excess of 226 days.

Now, obviously those movies aren’t for everyone (and many of them probably aren’t for anyone, save close friends and family). But—still. Movies. Lots. How does someone interested in cinematic criticism—or just even watching cool things—begin to navigate this abundance?

“‘You should only read what is truly good or what is frankly bad.’ – Gertrude Stein” — Hemingway

Writing is a matter of taste, criticism a manner of penetration.

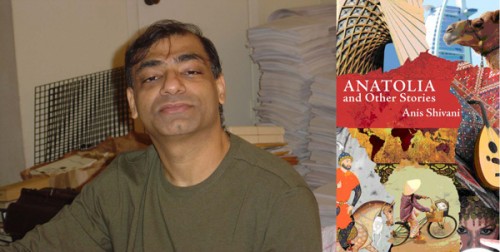

A Conversation With Anis Shivani

I am always fascinated by people with whom I disagree, vehemently and sometimes violently, about matters of mutual interest. I have read some of the literary criticism Anis Shivani has written for The Huffington Post and in other venues and regardless of his subject matter, I always have a reaction, usually a reaction that is anything but subdued. Nine times out of ten, I disagree with what Shivani has to say about everything and anything. I suppose that is the mark of a critic who is doing their job effectively–inspiring a reaction, a conversation, a response to their ideas. I am especially curious about what makes Shivani tick because he seems so committed to his opinions on the one hand, and so committed to provocation on the other, though, as you’ll see, he would disagree with that latter statement. I don’t know that you can ever really know how someone thinks or what motivates them but I asked Shivani a few questions about contemporary literature, criticism, the role of the critic, and how he approaches his critical work. He had, as you might imagine, a great deal to say and I disagreed, as you might imagine, with much of what he had to say but as ever, I had a reaction, a response and we had an interesting conversation.

You do a lot as a writer–fiction, poetry, criticism. What is your first love?

Fiction has always been my first love. I write criticism to learn more about fiction. I could also easily have devoted myself to poetry, but although poetry is satisfying in its way, only in fiction does my soul fully engage. There’s no rush like writing fiction, and I can’t do it on autopilot, as it’s possible to do with criticism or even poetry at times. The feeling of euphoria and satisfaction from writing fiction is incomparable. Writing a successful novel is a great challenge, and you have to be a bit of a poet, a bit of a critic, a bit of a dramatist, a bit of a philosopher, a bit of a social scientist, to pull it off. Writing long poems is more exciting than short lyrics, but then one needs a lot of commitment for that. I’m in two minds about having written so many stories early in my career; on the whole perhaps it was a net loss, because I didn’t spend that precious time writing novels. The economics of publishing dictated that I write short stories for many years and get them published in the literary journals, but the story requires a different mindset than a novel and it’s difficult to get the story’s habits out of the mind when one is writing a novel. It teaches compression, which is both a virtue and a fault.

It’s only an unfortunate specialization that limits writers to operating within narrow genres—short stories about a specific region and milieu, for example, or novels dedicated to the same few characters, or lyrical poems relentlessly exploring one’s own ethnicity or geography—otherwise writers in other countries still write in different genres at the same time, and this has always been the case since the beginning of time—until, that is, the academic specialization of literary writing under university patronage in the U.S. in the late twentieth century. I think writers should see themselves as workers in the broad field of the arts—including even Hollywood or popular music, and certainly what used to be called literary journalism in every possible genre. Anything to break the rut, to push the mind toward new challenges so that writing doesn’t fall into preestablished grooves—which is very easy to do, based on the successful formulas in existence. Film is a particularly fruitful cross-fertilizer, as is painting. Really, the arts cannot function in isolation and shouldn’t be practiced and critiqued that way. It’s only unprecedented specialization that has created this unnatural situation, and the writer must be very conscious of that and work hard to break down the false institutional barriers preventing a catholicity, even eccentricity, of interests. The mind desires to switch between different levels of intuition and emotion and logic and these desires should be fed.

June 22nd, 2011 / 4:39 pm

Strangely enough, Mr. Joyce has almost universally been denied the right to do on a larger scale what any Yankee foreman employing foreign laborers does habitually on a smaller scale, namely, to work out a more elastic and a richer vocabulary which will serve purposes unserved by schoolroom English… Those who cannot transcend Aristotle need make no attempt to read this fascinating epic. The ideas do not march single file, nor at a uniform speed.

Critics on Criticism: Dryden and Pope on the Evils of Hating, Loving Parts

Apparently something about the Restoration, after all the Charleses and Jameses and Cromwells and who is Catholic and who is Anglican or Puritan, got poets to thinking about the whole versus the part, w/r/t criticism. Thus John Dryden, who was politically moderate but eventually found he had some inclinations toward Rome, on critics who “think this or that expression in Homer, Virgil, Tasso, or Milton’s Paradise to be far too strained”:

Apparently something about the Restoration, after all the Charleses and Jameses and Cromwells and who is Catholic and who is Anglican or Puritan, got poets to thinking about the whole versus the part, w/r/t criticism. Thus John Dryden, who was politically moderate but eventually found he had some inclinations toward Rome, on critics who “think this or that expression in Homer, Virgil, Tasso, or Milton’s Paradise to be far too strained”:

Tis true there are limits to be set betwixt the boldness and rashness of a poet; but he must understand those limits who pretends to judge as well as he who undertakes to write: and he who has no liking to the whole ought, in reason, to be excluded from censuring of the parts. (from “The Author’s Apology for Heroic Poetry and Heroic License,” 1677)

This seems a good rule. I perhaps unfashionably quite enjoy reading good criticism for its own sake, and I believe a person can display a purely critical genius, though their work ought to follow Wilde’s dictum of being a creative act in its own right. I think, here, that Dryden makes a key distinction. He is taking to task critics who profess no taste for any muscular poetry, for the “the hardest metaphors and the strongest hyperboles,” and who then critique individual works of heroic verse that by definition display that muscularity, hardness, and strength.

Critics on Criticism: Oscar Wilde

From “The Critic as Artist”:

From “The Critic as Artist”:

To the critic the work of art is simply a suggestion for a new work of his own, that need not bear any obvious resemblance to the thing it criticizes. The one characteristic of a beautiful form is that one can put into it whatever one wishes, and see in it whatever one chooses to see; and the Beauty, that gives to creation its universal and aesthetic element, makes the critic a creator in his turn, and whispers of a thousand different things which were not present in the mind of him who carved the statue or painted the panel or graved the gem.

From “Blind and Dumb Criticism” in Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers:

From “Blind and Dumb Criticism” in Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers: