His Geography: The Collected Works of Michael Ondaatje

A. “There are stories the man recites quietly into the room which slip from level to level like a hawk.”

The English Patient

1. A popular mistake about Canada is that it is fundamentally North. Otto Friedrich’s biography of Glenn Gould compares Canada’s relationship to the North with America’s to the West, except there’s no Disneyland in the Arctic. Most of Canada’s population is concentrated in the southernmost quarters; post-Gould Toronto produced Petra Collins’ Instagram, among a lot of other non-Drizzy things. One quarter of all postwar immigrants to Canada came to Toronto. Canada’s history is only one centennial in; its youth relative to the rest of the world may account for why the rest of the world sometimes acts so strange about it. Cats still aren’t sure about humans because in evolutionary terms they haven’t been around as long as dogs and are still socializing themselves. There are no cats in the Bible, for instance.

2. The book of 2014, nonfic anyway, was Capital in the 21st Century by Thomas Piketty, a book carrying the mythical glow of pregnancy. Stephen Marche reviewed it for the Los Angeles Review of Books, calling it ‘perhaps the only major work of economics that could reasonably be mistaken for a work of literary criticism.’ He relates realism’s utter defeat of the other forms, the fun ones like lyricism or even minimalism, and credits Jonathan Franzen, that old serpent, with its proliferation. We already knew all that. One of the writers Marche suggests has fallen out of usage is the Canadian Michael Ondaatje: from Ontario by way of Sri Lanka, educated in England, known for hushed, haunted pieces like The English Patient (1992), Divisadero (2007) and The Collected Works Of Billy The Kid (1970). He also wrote a memoir, Running In The Family (1979), which includes the following clip:

“At St. Thomas’ College Boy School I had written ‘lines’ as punishment. A hundred and fifty times. [fragment in Sinhalese] I must not throw coconuts off the roof of Cobblestone House. [fragment in Sinhalese] We must not urinate again on Father Barnabus’ tires. A communal protest this time, the first of my socialist tendencies. The idiot phrases moved east across the page as if searching for longitude and story, some meaning or grace that would occur blazing after so much writing. For years I thought literature was punishment, simply a parade ground. The only freedom writing brought was as the author of rude expressions on walls and desks.”

3. Ondaatje’s family is Dutch-Ceylonese and was well-off. By various vagaries his father ended up a chicken farmer, his mother on staff at a hotel, and he and his siblings diffused thru England, America, and Canada. Much of his writing is liminal: the act of falling on a map, and why is it called falling? ‘We are the real countries’, vows a character in The English Patient. Disdain for colonialism and its legacies is a chief Ondaatje engine; another character in The English Patient insists that everyone white is motivationally English: ‘when you are bombing brown races you are an Englishman’. That character’s name is Kim and he’s Sikh, which we know because he wears a turban. Almasy, the sophisticated count burned into patienthood if not Englishness, is Hungarian but nomadic. He hates ownership, being owned—and the idea that when there’s a war on, where you’re from becomes important.

Ondaatje produces fantasias of language, requiring much suspension of disbelief, risking collapse if pulled too far out of context. As stated by Pico Eyer in an essay for the New York Review of Books called ‘A New Kind of Mongrel Fiction’: ‘ there will always be some for whom Ondaatje is too rarefied or exquisite.’ Lines like ‘giraffes of fame’ and little leashes of them like ‘later my hands cracked in love juice/fingers paralyzed by it arthritic/these beautiful fingers I couldnt [sic] move/faster than a crippled witch now’ qualify as sentimental dithering to the worst agnostics. Glenn Gould said he believed in God as long as it was Bach’s; I believe in a groundless, fermented prose style as long as it is Ondaatje’s. Even when it’s a little bit bad, it is never not beautiful.

‘There is nothing wise about a harbor, but it is real life. It is as sincere as a Singapore cassette. Infinite waters cohabit with flotsam on this side of the breakwater and the luxury liners and Maldive fishing vessels steam out to erase calm sea. Who was I saying goodbye to?’

Ondaatje, Running In The Family

October 3rd, 2014 / 10:00 am

Arts, Process, Edit

In France*, cheese-making is really two processes. On dairies, milk is collected from cows, goats, or sheep, is cultured, maybe cooked, somehow molded. That is the first process. After that, an affineur takes over. The whole job of an affineur is to age cheese. Keep it at the right temperature, rotate it, maybe dust it off from time to time. When you hear about cheese caves, that’s the affineur part. In the small-producer cheese world, the affineurs are the stars, the ones whose name you would know if you worked in that industry. Pierre Androuet, Herve Mons, Marcel Petite (O the Comte from the cellars of Marcel Petite!). One affineur might get wheels from several different trusted dairies, whose names never make it on the packaging (unlike in the US, where most cheeses seem to be branded by farm/dairy).

In France*, cheese-making is really two processes. On dairies, milk is collected from cows, goats, or sheep, is cultured, maybe cooked, somehow molded. That is the first process. After that, an affineur takes over. The whole job of an affineur is to age cheese. Keep it at the right temperature, rotate it, maybe dust it off from time to time. When you hear about cheese caves, that’s the affineur part. In the small-producer cheese world, the affineurs are the stars, the ones whose name you would know if you worked in that industry. Pierre Androuet, Herve Mons, Marcel Petite (O the Comte from the cellars of Marcel Petite!). One affineur might get wheels from several different trusted dairies, whose names never make it on the packaging (unlike in the US, where most cheeses seem to be branded by farm/dairy).

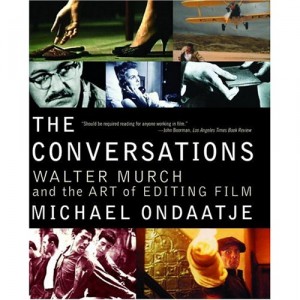

So it goes with films–the editing is done by someone else, not the director or screenwriter. Walter Murch was the editor and/or sound editor (he’s the only person to win Oscars for both) of Apocalypse Now, The Godfather II, The Conversation, and many many others. His work on The English Patient acquainted him with Michael Ondaatje. The two had a series of conversations/interviews (Ondaatje is asking the questions, primarily) that are collected in a book called The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film.

The book is a trove. I’ve been meaning to write about it here for over a year (!), but I’m still not all the way through it. Obviously, I’ve put it down a lot, but also I just really want to take my time with it because there is so much to learn and reflect on. I’m fascinated by how these two men, both of whose work I adore, find these nexuses between film editing and book editing. It’s a reminder of how much we as word-people have to learn from people who work in other media. The reason I started with the cheese example is that the big overarching thing the book makes me think about is the relationship between making and aging/editing/tending/revising. Below are a few passages that stood out for me. But really, you should have this book. It was assigned to me in grad school by the great Susan Bell, author of The Artful Edit, which, if a friend hadn’t made off to California with my copy, would get its own post. But with all respect to Bell and Stunk and White and the rest, The Conversations is the best writing manual (not that it’s trying to be) that I’ve ever read. So, here are some bits (O for Ondaatje and M for Murch):

M: It’s a stage in the process I call “editing with eyes half closed.” You can’t open your eyes completely, which is to say, you can’t express your opinion unreservedly. You don’t know enough yet. And you’re only the editor. You have to give everything the benefit of the doubt. On the other hand, you can’t be completely without opinion, otherwise nothing would ever get done. Putting a film together is all about having opinions: this not that, now not later, in or out. But exactly what the balance should be between neutrality and opinion is a very tricky question. The point is, if you squash this down, then you push the whole curve of the film down, whereas it might have righted itself by its own mysterious means. If you try to correct the film while putting it together, you end up chasing your own tail.

In Praise of Modesty

The writer was a tumbler. If not, then a tinker, carrying a hundred pots and pans and bits of linoleum and wires and falconer’s hoods and pencils and…you carried them around for years and gradually fit them into a small, modest book. The art of packing. — Michael Ondaatje, Anil’s Ghost

I think of this quotation a whole lot. I think a whole lot of this quotation. Blake’s interview of Andrew Zornoza made me think of it, the 14 years in the making part. My friend working around the clock on what will be a short non-definitive but brilliant biography made me think of it. Avatar and not wanting to see a movie that proposes to break new ground, that promises to change the way I think of the movie experience, made me think of it. Immodesty is dishonesty. To think we’ll never read another book after this one. To think we’ll never see another movie, or that ever after we’ll see movies differently. To think we won’t amend and mend and expand and retract our thoughts about art-making because this time we’ve gotten it right. What hubris.

This is not to equate modesty with small physical size. This is not to equate modesty with lack of ambition. To pack, select, winnow, whittle, fit, shape, pat, balance, attend, await, and weigh the materials of life and art to make a book is honest hard work–backbreaking, eye-straining, near-impossible work, and the reward always comes too late.

A quote like this gives postmodernity a good name. To admit to sweeping up shards, gathering scraps of broken meat, to allow that one book can’t hope to contain the Whole, or even any one whole. The days of circumnavigating the globe, the days of the brave frontier have passed. Foreclosed. We have now vaster materials, but smaller places to put them in. What possibility, what call.

Vicarious MFA: Family Time!

Books read since last post: Running in the Family by Michael Ondaatje and Life on the Outside by Jennifer Gonnerman.

Michael Ondaatje

In Non/Fiction we discussed Running in the Family, a beautiful memoir of Michael Ondaatje’s unbelievably lush, gin-swilling family who lived on Ceylon, an island off the coast of India. Some people in class were disappointed/confused that Ondaatje didn’t really approach the whole colonialism aspect of a British family living in India and having servants. Most people didn’t care that much because they were distracted by the beauty of the book. Each chapter reads like a prose poem and there’s no overt narrative arc. It’s more like a book of poetry masquerading as a memoir.

For The First Book seminar we read Jennifer Gonnerman’s Life on the Outside, a ridiculously impressive book about Elaine Bartlett, a woman

Elaine Bartlett (Photo by Heather Conley)

who was sentenced to 25 years of jail time under the Rockefeller Drug Laws after being set up by a drug dealer working for the cops. The book focuses on the Bartlett family’s struggle to make ends meet before, during and after Elaine’s prison time. She served 16 years before being granted clemency in 2000. I can’t even begin to explain how well this book was written. The amount of information Gonnerman gets the reader to understand and remember about Elaine’s set up, her huge family, the Rockefeller drug laws, and the myriad complications before and after the jail sentence is nothing short of phenomenal. The Rockefeller drug laws were repealed by Gov. David Patterson last week and Elaine Bartlett’s story had an impact in that decision.

Read for Next Week:

Non/Fiction: Oh, wait, I forgot. Will update this later today.

The First Book: The Virgin Suicides by Jeffery Eugenides

And of course, workshop submissions.