Mr. Mercedes by Stephen King

Mr. Mercedes

Mr. Mercedes

by Stephen King

Scribner, June 2014

448 pages / $30 Buy from Amazon

Like many writers my age (31), I probably wouldn’t be one if it weren’t for Stephen King. At 16, finding the idea of short story writing woefully unambitious, my early attempts at novels were thinly-masked Stephen King impersonations. Based on the malodorous work that turns up in self-publishing, writers’ workshops, and slush piles, I’m not alone in that my first fictional efforts reeked of The King.

His influence isn’t necessarily a bad one. King became a best-selling author thanks to his expert pacing, gift for metaphor, wry sense of humour, and a number of intangible talents. Adam Ross and Justin Cronin are recent devotees who demonstrate that even elite ‘literary’ writers can benefit (both financially and creatively) when they borrow from King’s bag of tricks.

The most important way that King aided in my development is that his work has always been littered with literary and cultural references. (In recent years, he’s been obsessed with Philip Roth, comparing the reception of his own work to Roth’s in essays, and frequently bringing him up in fiction.) In this way, King inadvertently sabotaged my love for him. He’d reference Jack Kerouac or Norman Mailer, and their writing would end up on the bookshelf in my childhood bedroom. With all those major works waiting to be read, I found myself in a situation described by Arthur Conan Doyle in The Magic Window, a short volume that celebrates the contents of his book collection.

“It is a great thing to start life with a small number of really good books which are your very own. You may not appreciate them at first. You may pine for your novel of crude and unadulterated adventure. You may, and will, give it the preference when you can. But the dull days come, and the rainy days come, and always you are driven to fill up the chinks of your reading with the worthy books which wait so patiently for your notice. And then suddenly, on a day which marks an epoch in your life, you understand the difference. You see, like a flash, how the one stands for nothing, and the other for literature. From that day onwards you may return to your crudities, but at least you do so with some standard of comparison in your mind. You can never be the same as you were before.”

September 1st, 2014 / 10:00 am

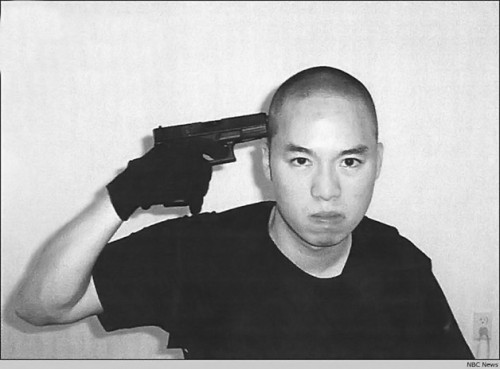

Boys Who Kill: Cho Seung-Hui

The next installment of Boys Who Kill stars Cho Seung-Hui, or Seung-Hui Cho, or Question Mark. On 16 April 2007, 4 days before the 7th anniversary of Columbine, Cho killed 32 people at Virginia Tech. First he visited West Ambler Johnston Hall, a dorm room for both boys and girls, where he killed one boy and one girl. Then he traveled to Norris Hall, a classroom building, and killed 30 more people.

Ever since Cho was taken out of his mommy’s tummy he hasn’t taken to talking. “Talk, she just him to walk,” says Cho’s great aunt about his mommy. “When I told his mother that he was a good boy, quiet but well behaved, she said she would rather have him respond to her when talked to than be good and meek.” At Virginia Tech, one of Cho’s roommates remarked, “I would see him walking to class and I would say ‘hey’ to him and he wouldn’t even look at me.” Other students concluded that he was a deaf-mute. He ate myself all by himself, and when someone offered him 10 dollars to say something, he said nothing. According to medical professionals, Cho suffered from “selective mutism.”

I, too, would prefer to be mute, and so, it seems, do other boys. Holden Caulfield dreams about being a deaf mute, and, it’s been reported by various biographers that instead of engaging in dinner table conversation, Arthur Rimbaud would just growl. Talking is terribly human — this race of creatures does in it grotesque quantities: they talk at Whole Foods, at overpriced bars, at trendy coffee shops, and, obviously, through Gmail, Gchat, texts, Facebook, Twitter, Disqus, and so on.

Cho’s contempt for normal communication distinguishes him from humans. Virginia Tech students and teachers constantly construct Cho as boy who confound expected human behavior. A professor labeled him “disturbing” and “unusual.” A student in his playwriting class said Cho “was just off, in a very creepy way.” According to Nikki Giovanni, students started skipping her poetry class due to Cho’s behavior . When Nikki told him to either cease composing sinister poems or drop her class, Cho replied, “You can’t make me.” Eventually the then head of the English Department, Lucinda Roy, tutored him privately. But even Lucinda was afraid of him. During the one-on-one tutoring appointments, Lucinda and her assistant agreed upon a code word that would prompt the assistant to summon security when uttered.

Based on this testimony, Cho is similar to a virus or a disease. No one wants to be around him; everyone is horrified of his presence. Not one to stay up into the wee hours of the morning to drink, party, and partake in sexual intercourse, Cho went to bed early and awoke early. He also played basketball alone. According to the New York Times, Cho was in a “suffocating cocoon.” (Being in a “suffocating cocoon” seems very dramatic and cosy; it also seems as if a “suffocating cocoon” would provide protection from mankind.) Virginia Tech journalism professor Roland Lazenby sums up Cho as a “shadow figure, locked in a world of willful silence.” Both Lazenby and the Times portray an incomprehensible boy who, isn’t free and liberated like Western subjects, but is held captive by a dark dangerous force. As Theresa Walsh, a girl who witnessed the killings in Norris Hall, says, “I’ve never really thought of him as a person. To me, he doesn’t have a name. He’s always been just the ‘the shooter’ or ‘the killer.'”

season-o-giving

77. Is it ever a good idea to give your book away?

14. Relatives of writers really tussle with what to give them; who wants another giant book of 500 bad poems? If asked, what do you tell people?

1. What’s the highe$$$t you’ve ever given for a book, any book? Do tale.

9. You know what writers really need? Nothing but time. I once wrote a grant (a process about as fun as boiling gravel) and received that grant and it was worth several thousand dollars and what did I want, those grrrrrr-anters asked? Time. So they paid someone to teach my class that semester while I wrote (and played a smidgen of disc golf). Time. Capital T. (This an argument for the MFA, BTW, but I don’t wanna start that withered face of an apple turning over.)

111. Who gives a shit? (And he read Jest on tape while night-walking Maine highway shoulders)

018. Advice: Don’t give breached things. It’s general knowledge I’m addicted to hot sauce (a key aspect of nachos). Years ago, a student gave me a bottle of hot sauce (though post final grades in this case, the student gift thing is already weird/odd for me. I never know what to do except discourage). The bottle was open, half contents gone. Another time a friend gave me an expensive bottle of bourbon as congratulations for a life event. He then cracked it open, took a preternatural swig, and drank half the bottle his own self. Don’t.

Does the used book fall under this rule?

4 crowbars eating fries

1. This Stephen King piece by William Walsh is exactly why I glow persona fiction. Not sure how I missed this. Maybe it was even noted here (I’m too lazy to look now). Anyway, enjoy. I think this piece is using the persona (King), its echoes, connotations, in a way I really admire and enjoy. Walsh is waltzing the term “Stephen King” in a technical manner. The King character is an object/emotion/thought process. It enacts a void and need and unspoken thing for this family. It…oh, I could go on, but why not read?

2. Sardine sandwiches do rock. (1:56 to end made me fly/why like a detail) I am serious now, go watch. Isn’t it what we like and need to live? Isn’t it a good story, or better a poem? If I could meet one sardine sandwich woman a day, this very life would be enough.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZ872YZCPG8

3. Here are some crystals for sale at a reasonable price. They were found in Tao Lin, China.

4. I am sick, feverish, that somebody-stuffed-wet insulation-in-my-head-cavities thing, something, but just ignoring it because I have a lot of work to do. Does anyone like to write when ill? I have been writing the last two days and my fingers are large, like balloons (those party ones clowns make into dachshunds) floating over the keys, all tinnitus and forehead simmer. I’m not sure what it means to the words on the page. You?

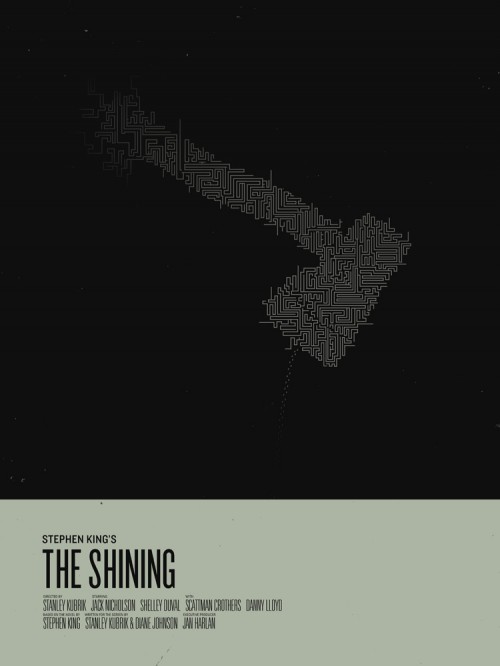

Designer Nick Tassone (alias bee combs) makes posters for films based off Stephen King novels, all of which I really like. They are conceptually gratifying and an unfortunate anomaly in the movie poster business; that these are from a school project make it that much more impressive.

Q: Hey, did somebody say “Justin reviewed the new Stephen King for Bookforum?”

A: No, nobody said that.

Q: Oh, okay then.

Family Guy Stephen King Tribute Episode

For no particular reason, Family Guy has just done an episode of their own adaptations of Stephen King stories. I watched the episode on hulu yesterday. It won’t stay up there too long, since they only have 5 episodes at any given time, but I think it just went up. The Family Guy episode follows the basic pattern set by the Simpsons’s annual Treehouse of Horror specials, only without the peg to Halloween. The only thing about this that’s a bummer is that they parody the movies made out of the books, rather than the books themselves. Given that the guy is one of the best-selling writers on the planet, it stands to reason that they could have snagged at least ONE of his unfilmed stories to send up. Oh well. The first one, a parody of Stand By Me (published as “The Body” in King’s novella-collection Different Seasons) is definitely the strongest of the three. The second one is a parody of Misery with Brian as the kidnapped writer and Stewie as Annie Wilkes, and the last one is a pretty faithful re-creation of The Shawshank Redemption (originally published as “Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, also in Different Seasons). Fun fact: three out of the four novellas in different seasons have been made into films. The third is “Apt Pupil,” about a kid who discovers his neighbor is an ex-Nazi, but instead of turning him in blackmails him and then becomes his sort of weird partner in crime. The movie had Brad Renfro, I think. The last story in the collection, “The Breathing Method,” is the only one not to have been adapted, and odds are against its ever being done. It’s understated, but basically weird as hell– a sort of drawing room ghost story with some weird Lovecraft shout-outs tossed in for good measure.

“THAT’S *IT*! YOU AREN’T WERE IN MY MAGAZINE ANYMORE!” and other bizarre things you can (but shouldn’t) say when you edit an ‘electronic magazine,’ or ‘elecamazine,’ as I call it.

Anyway, here’s Matt addressing Blake:

>>Thanks, again, for being honest. That’s why HTML Giant is awesome.

I like being a stick in the mud as well, which is why I just removed your story and bio from the Thieves Jargon archive.<<

This caught my attention, because something very similar was said to me recently after I made some disparaging comments about my own work which had appeared in a back issue of a certain web journal which will not be named. (Mine came in the form of a threat; I haven’t checked to see if it was carried out.) Basically the editor’s thesis was, if I was critical of my own work, and by extension her magazine for publishing it (fairness to her: I was, and am) then fuck me too and she would “un-publish” me as a punishment.

I don’t know Matt, and I don’t read Thieves’ Jargon, so I’ve got nothing to say about him or his project that’s based on research or first-hand experince. But his comment, which may well have been made in jest, for all I know, really stuck with me, because in both cases–mine, and his, assuming the comment was in earnest–there seems to be a prevailing and unquestioned assumption that the purpose of publishing writing is to generate for the author a kind of “capital” or “currency,” which is then in some psychic sense “owed” to the editor, who seems to see him/herself as a sort of issuing bank.

This is a very bad way to think of yourself as an editor, and about the purpose of your editorial project in general. Of course, we know that at a certain level it is the truth of the case–a writer indeed does “get” something very real, albeit intangible (I don’t mean the check) from being in The New Yorker that s/he don’t get from being in Bicycle Goat Review. (Though, conversely, depending who you want to impress, you may well get something from Bicycle Goat that you don’t or can’t from the NY’ker. )

The question, to me, is whether generating this “currency” is the primary goal of the publication or just a happy side-effect. Answering this question is really easy. If you have to think about the answer to it for even a second, or if you are coming on the end of this sentence I’m typing now and still don’t know the answer, let me give you a clue: DON’T EDIT ANYTHING. YOU’RE NOT READY AND YOU WON’T BE GOOD AT IT.

When an editor of an electronic journal, who is in the unique situation of being able to “unpublish” in a way that no print editor can, threatens or actually carries out such an action, what they seem to reveal to me is the cravenness and intellectual bankruptcy of their own enterprise. When you do this, you deal a serious blow to your project’s institutional memory, its continuity, and its integrity. Plus you give a fiendishly literal twist to the phrase “So and so has been published in Bicycle Goat” as it appears in three-line bios all over the face of this great world.

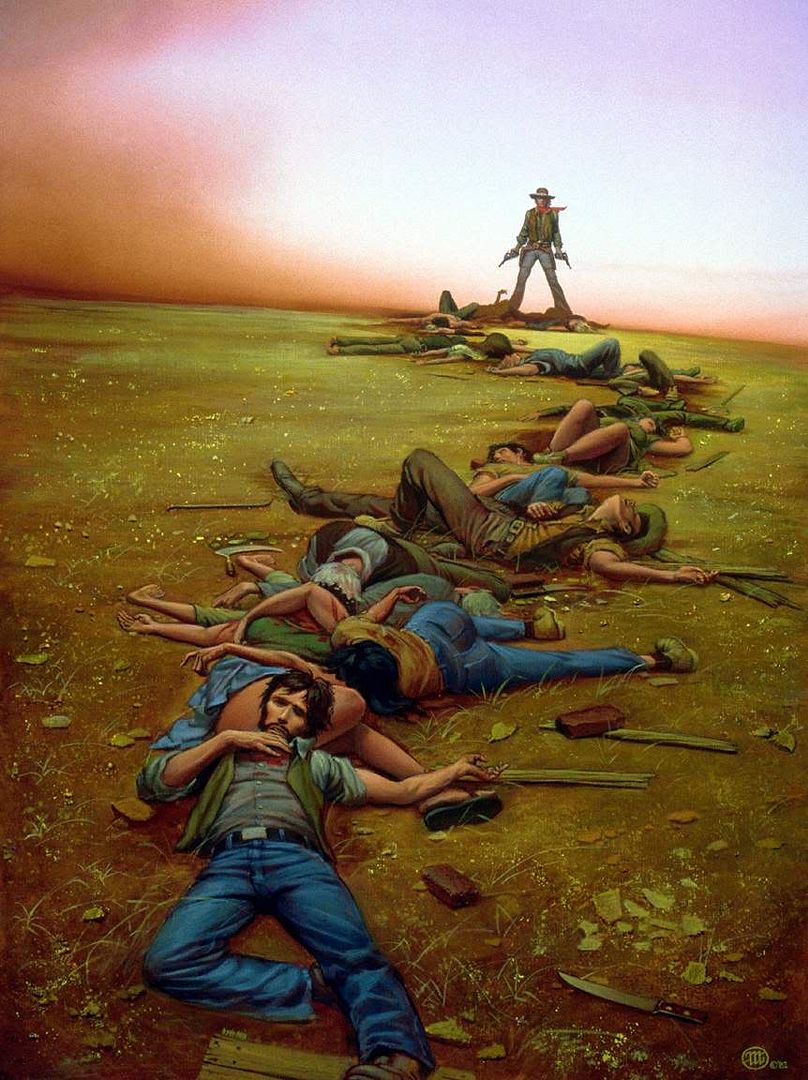

Mourning the victims of Stalin's purges.

One of the most important things an editor can do is stand by the work he or she has published, even if–especially when–the author no longer does. We expect the author to grow and change, and maybe even to disown old work to make way for the new. The editor–especially when s/he is also the publisher and sole proprietor of the enterprise–is supposed to be a somewhat more practical cat, and to have a somewhat longer view of the situation.

Questions: if you “unpublish” me from your journal, does that mean my work is unpublished now? Is this like being a born-again virgin? And if I have a second change of heart, and love my work again, can I take the stuff you removed from Bicycle Goat and send it over to A Public Space? If/when my book comes out, and my work that you un-published is in it, should I put your journal on the copyright page like this: “Dinosaurs are Awesome” first appeared in Bicycle Goat A Public Space.

Crisis on infinite earths! Oh noes!

I’ll be the first to argue that editing and curating are artistic endeavors–at least as much as writing is–so if you want to disown an entire editorial project, that’s one thing, but to re-evaluate and selectively remove work you actually enjoyed and admired and were proud to publish based on personal offense at that writer’s (a) behavior, (b) lack of quid pro quo, (c) change of heart in re their own work and/or your magazine, (d) other, makes you one thing and one thing only: a bad editor.

Sorry, kids, but them’s the breaks.

Purity of heart is to will one thing.