Two Lines Press: Interview w/ Scott Esposito

HTMLGIANT recently featured a review of The Fata Morgana Books by Jonathan Littell, published by the fantastic Two Lines Press that is bringing some splendid international works into English. I had a chance to ask Scott Esposito some questions about the press.

***

Janice Lee: What is Two Lines Press and what sets it apart from other publishing projects?

Scott Esposito: Two Lines Press is a nonprofit publisher of exclusively literature in translation. We’re akin to a number of nonprofit translation publishers (e.g Archipelago Press, Open Letter Books), but I think there are a few things that set us apart.

First off, I’m not aware of anything like us in the San Francisco Bay Area (where we’re headquartered), which I think is significant. We do a number of events in the community each year, and we’re in contact with some of the best local bookstores. I think it’s an important thing to have a press like us pushing the translation line around these parts.

We also have a journal of translation (in addition to publishing books) called TWO LINES, not something that most translation presses can boast. For 20 years has been published annually, and starting in Fall 2014 it will publish twice-yearly. The journal has worked with a lot of the best people in translation, and I do think it’s a pretty special thing to have on with us.

Then there’s the fact of our literary aesthetic. Most translation-only presses are such small, intimate operations that the prejudices of the staff and their tight circle of translation friends really shines through. I don’t think it’s too much of an exaggeration to say that we have our own particular take on what constitutes “great literature.”

And maybe one more thing: we have our own podcast called That Other Word that I cohost with the incredible Daniel Medin of the Center for Writers and Translators at American University in Paris. We do a 15-minute segment of new translation recommendations and then a 45-minute interview with a translation professional. Past guests have included Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Lorin Stein (of The Paris Review and FSG), Ethan Nosowsky (of Graywolf), Sylvia Whitman (of Shakespeare & Co in Paris), Margaret Jull Costa, Petra Hardt (of Suhrkamp).

JL: It seems that there’s been a renewed interest in translated works in recent years and more publishers concentrating on bringing more unknown works to the US. Does this seem to be the case for you? And if so, why do you think this is?

SE: It’s possible—Chad Post tracks the number of fiction translations published each year, and the number has been increasing over the past few years. Although, it is hard to tell if this is a trend or an aberration right now. (For instance, that number was bumped up significantly by the creation of AmazonCrossing, which accounted for nearly 10% of the total in 2012, but those books were largely horrible titles that have no literary value, and it looks like Amazon is now backing off of publishing.)

But definitely there is more of a conversation around translation, and more of a sense of shared mission and solidarity among the people in the community. You can ascribe some of that to the community-building enabled by Internet technologies, and initiatives like the PEN World Voices Festival or the Best Translated Book Award.

But, in my opinion, the most significant reason for any renewed interest in translation is because this is where a lot of the literary innovation is occurring these days. There are kinds of fiction available in translation that are simply not produced here in the U.S. When I think of titles like Blinding by Mircea Cartarescu, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle sextet, the work of Roberto Bolaño, Hilda Hirst, Laszlo Krasznahorkai, just to name just a few recent examples, it’s very clear to me that fiction like that is not being written by American writers.

As serious writers and readers here in the U.S. have become interested in having new experiences and expanding their artistic horizons, I think it’s been a very natural thing to look abroad for new influences.

SE: For me, the biggest pleasure is the privilege of being among the first to read some of the best of the best literature from all around the world. Editing at a translation press is like having people hand-pick the very best books they can find from all over the globe and then deliver them to you. That’s an amazing position to be in.

One thing that’s both a challenge and a pleasure is working with translators. It’s a pleasure in the sense that translators are some of the most articulate, knowledgeable, passionate book people I’ve ever met. Getting to correspond with them daily and hang out with them at conferences and such is such a treat, and it’s made me a far better reader, writer, and person. Working with them is a challenge in the sense that you have to develop a different set of editorial practices in order to work with a translator, as opposed to directly with the author. It can be tricky to edit and evaluate something when you’re actually reading someone’s interpretation of an original text. This is even more of a challenge when you consider that in translation there is never any “right” answer—on each page you are forced to choose the best compromise among a host of options with their own pros and cons.

The other challenge is strictly practical: translations come with their own particular expenses, we’re often reliant on readers to report on books for us, and, despite gains, it still is hard to market translations and get press attention for them. All of that makes it a lot harder to stay above water (one of the reasons we are a nonprofit).

SE: As a huge fan of Laszlo Krasznahorkai, I can’t help but anticipate another Krasznahorkai title that Ottilie Mulzet is working on right now (she’s the one who did that incredible, incredible translation of Seiobo that just came out this fall). It’s called Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens and it will be appearing with Seagull Books, one of the most interesting translation presses to come on the scene in recent years. For a preview of this title, you can read more about it in Issue 2 of the journal Music & Literature. (I’m also pretty sure Ottilie discusses it in an interview I conduct with her in the same issue. If not, read it anyway—her discussion of Krasznahorkai’s career should be a no-brainer for any fan of his work.)

Open Letter is set to publish two books by the Chilean author Carlos Labbé: Navidad & Matanza and Locuela. I’ve read the latter in Spanish and the former in English, and I think Labbé has huge potential to be one of the best recent discoveries from Latin America.

NYRB Classics is doing this giant selection of Balzac’s short stories, which I am hugely excited about. I am an unabashed Balzac fanatic, a person who thinks every creative writing student in the country should read his best work and try their best to achieve even 1/8th of his magnificence. Any time I see a Balzac translation that I do not own, I immediately buy it, and then I read it. So 400 pages of mostly untranslated stuff is a blessing.

As a big fan of Edouard Levé, I’m excited to see that Dalkey Archive is publishing his Works in 2014. This title consists of a list of his potential literary projects. And there is also Melancholy II by Jon Fosse. The first volume of Melancholy was one of the darkest, toughest, most Bernhardian texts I read in 2013.

My colleague CJ Evans adds that he’s excited about the Henrik Nordbrandt title When We Leave Each Other forthcoming from Open Letter Books. He’s also looking forward to Grzegorz Wróblewski’s Kopenhaga, forthcoming from Zephyr.

SE: Of course! Next year we are doing a remarkable book called Baboon by one of Denmark’s leading authors, Naja Marie Aidt. It’s a series of utterly bizarre short fictions, each of which just keeps accelerating until it achieves this kind of demented headlong force. Reading the book as a whole is kinda amazing. As I read each fiction sequentially, my eyebrows kept raising higher and higher until I think I strained a muscle. She really achieves this strange aesthetic territory that is wholly her own, insofar as I can tell.

Then after that we are doing this book called Self-Portrait in Green by Marie NDiaye, which is a completely absurd “memoir.” NDiaye claims that this book is about herself, but it has dead women roaming around it, all these “women in green” who keep popping up and freakishly menacing her, a section where she visits her estranged father in Africa that I’m still not totally sure whether is a dream or not. It’s a really crazy, extraordinarily well-written (and extraordinarily well-translated) re-imagining of what a memoir is.

SE: I guess I’d just like to say that if you are one of those people who loves translation and loves the presses that publish translation, then take a moment right now to purchase a subscription to one of them. I can’t tell you how happy you will make that press. As a publisher, subscriptions are just about the best thing ever. Not only is it great to know that readers put that much trust in our editorial vision, but it’s also really, really helpful on a purely practical level: knowing that we have a list of people who have already signed on to purchase our books no matter what really frees us up to not think about sales to such a large extent and to do the really risky projects. So whether it’s us or Archipelago or Open Letter or And Other Stories or whomever, get that subscription.

Scott Esposito is the co-author of The End of Oulipo? (Zero Books, 2013) His work has appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, The White Review, Bookforum, The Washington Post, The Believer, Tin House, The American Reader, Music & Literature, and numerous others. He edits The Quarterly Conversation and is a Senior Editor with TWO LINES.

December 10th, 2013 / 11:35 am

Sonnets From a Vague Suburb

The Sonnets

The Sonnets

by Jorge Luis Borges

edited by Stephen Kessler

Penguin Books, 2010

336 pages / $18 Buy from Penguin Books, Buy from Amazon

Although justly famous in this country for his short fiction, Borges the poet remains largely unknown to American readers. This dual-language collection of his sonnets can go a long way towards remedying that deficiency. From his early atmospheric verse in Fervor de Buenos Aires, to his late poems of aging, nostalgia and death, written in the penumbra of near total blindness, Borges left behind a remarkable body of poetic work. We are still waiting for the complete works of Borges to be translated into English, but meanwhile, translator and editor, Stephen Kessler, has collected all of Borges’ sonnets into a single volume. Most of these were written when Borges was on his way to total blindness. The sonnet as a form called out to him in its succinctness and melody. Like oral poets of old, he found formal devices aided his memory, and so he composed sonnets in his head. The content of the poems is eminently recognizable to readers of his prose: the evocativeness of run-down suburbs, dusk, the gaucho, the warrior, the labyrinths of reason, the mysteries of time, identity, and mirrors.

November 14th, 2011 / 12:00 pm

Phone is ringing, oh my gawd, it’s a giveaway

Telephone is a new journal. Here’s their introduction:

The first issue features poems by Uljana Wolf which are translated by Mary Jo Bang, Christian Hawkey, Susan Bernofsky and more (a damn impressive list; that “more” doesn’t mean “friends of the publisher”). They all translate the same poems, so you can contrast and compare (samples here).

Paul Legault and the editorial crew of Telephone are offering 5 copies of this first issue to htmlgiant readers with a contest. Here’s the game, according to Paul:

I think it would be a good idea to get people to mis/un/dis-translate Alexander Graham Bell’s first telephone message:

“Watson, come here! I want to see you!”

And give 5 books to the best five, as judged by the editors.

I take that to mean: translate Bell’s first message any way you want. Do it in Spanish or Klingon or English or whatever. Translation is hip, as Lord Buckley showed Groucho Marx. **UPDATE: Entries must be posted by 12pm Eastern on Friday the 17th.**

And set your cell to vibrate this Friday at their release party:

Time: September 17 · 7:30pm

Place: 177 Livingston, Brooklyn, NY

Freaking NYC man. This looks like a great reading.

“Published in the future.” (“A screaming comes across the sky,” translated 56 times. Here.) Also, hey. I’m reading Against the Day.

Listening In

-There’s a piece called “How to Unfeel the Dead” by Lance Olsen in Artifice that knocked my socks off.

-A review of Edith Grossman’s Why Translation Matters, something I’ve been thinking a lot about. Richard Howard summarizes Grossman’s thesis:

In the end, Grossman warmly (after all) and gratefully rehearses the twofold answer to the question of her title: translation matters because it is an expression and an extension of our humanity, the secret metaphor of all literary communication; and because the creation of any literary translation is (or at least must be) an original writing, not a pathetic shadow or tracing of the inaccessible “original” but the creation, indeed, of a second — and as we have seen, a third and a ninth — but always a new work, in another language.

-I was tired this year at the AWP Conference. I couldn’t sleep past 5am, and my head swam in treacherous waters all day. New CollAge magazine had a table—we sold about 2.5 copies—at which I sat for 15-20 minute intervals before getting the jitters and flying the coop. Lots of wandering around the Denver Convention Center, admiring the big blue looming bear, sneaking peaks at the car show, listening in:

IN THE HALLS

I can’t just get drunk and flirt with all the students—

Jesus wouldn’t come down and have sex with me like that.

I feel like my arms look like big white baby harp seals.

I’m glad nobody got raped.

I got my MFA in deleting words. I don’t know anything

about throwing babies.

20 Important Books in Other Languages; or, “a list always growing longer”

A post re:– neither repost nor riposte–Blake’s wichtige Liste and (only at first) about Infinite Jest in German. Maybe a chair is a good metaphor for who gets translated. Have you been translated? Have the Important Writers on Blake’s list? And not 25 because Saramago, Ouredník, and Zizek are already others, Ben Lerner’s a poet, Aase Berg’s both, and I’ll write about poets in translation and translation in poets at an other time.

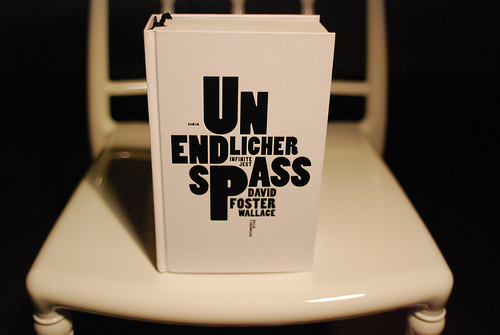

Not sure if anyone went there during all the well DFW grammar talk (thanks, Amy), but imagine translating, say, Oblivion. Good that one of Wallace’s German translators, Ulrich Blumenbach, did just that, presumably (it first appeared in 2006), while whittling away at Infinite Jest, which took him six years and has had, as Unendlicher Spass (literally, the less Shakespearean Unending Fun), endless success: ten times the expected five grand copies have been sold since it appeared at the end of August, on the heels of Infinite Summer, which the publisher, KiWi, has translated too, as 100 Days of Infinite Jest (in German–it ended on 12-1).

In an interview with Der Spiegel, Blumenbach (pictured–in German) regrets that the author never answered his many questions, “a list always growing longer”: it seems Wallace had grown weary of taking translator’s queries, and, according to The Complete Review’s useful paraphrase of a slippery summary (still looking for the original source), considered the Spanish La broma infinita (tr. Calvo and Covian | Mondadori, 2002) and the Italian Infinite Jest (Nesi w/ Villoresi and Giua | Einaudi, 2006) and apparently other attempts (anyone know more?) to have “all failed, more or less.”

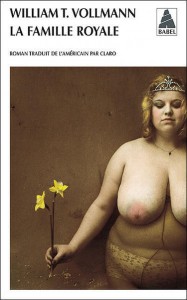

In a warm war, France is responding with (900 pp. of) Vollmann’s Rising (not translated by the great Claro, see below, who did six previous tomes, but by one Jean-Paul Mourlon, translator, it seems, of Jimmy Carter and Hilary Clinton). There’s also German Vollmann (3 titles), Spanish Vollmann (3 more), Japanese Vollmann (2), Greek Vollmann (2), and Czech Vollmann, all (not counting the French) with only one title (Butterfly Stories) repeated.

In a warm war, France is responding with (900 pp. of) Vollmann’s Rising (not translated by the great Claro, see below, who did six previous tomes, but by one Jean-Paul Mourlon, translator, it seems, of Jimmy Carter and Hilary Clinton). There’s also German Vollmann (3 titles), Spanish Vollmann (3 more), Japanese Vollmann (2), Greek Vollmann (2), and Czech Vollmann, all (not counting the French) with only one title (Butterfly Stories) repeated.

American Genius is only a Great American Novel for now (does it even have a British publisher?), despite Tillman’s first book of stories, Tagebuch einer Masochisten, having appeared in Germany in 1986, four years before her first collection in English, READ MORE >