ALL THE TEXTS I’D SEND YOU IF YOU WANTED TO GO TO A SERGIO DE LA PAVA TALK WITH ME ON DEAD RUSSIANS

…but then got ran over by a bus and died. No im totally kidding! but you really did get the flu and couldn’t join me.

The talk was at Housing Works, and it included two other speakers: David Gordon and Michael Kunichika.Your expectations were unclear: talk about Russian writers who, though they left us long ago, remain potent presences for readers and writers today. From Dostoevsky and Tolstoy to Vasily Grossman and Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, we’ll learn about obsession, madness, realism, fables, and more, in an event with all the drama and pathos (well, at least some of the drama and pathos) of the great Russian novels themselves.

Here are all the texts I would have sent you, in chronological order and without clarifying who said what, because color-coordinating via SMS goes a step too far:

truth-seeking urgency intrinsic in russian lit

antithesis to beckett & writers who focused extensively on beauty of language

falling in love w/ english language, less plot driven urgency

dostoevsky similar to conrad in terms of truth-seeking urgency

multivocality of dostoevsky

there is no right, just different truths

dostoevsky threw the best literary parties (metaphorically speaking, as a creator)

proust s parties were too long, and maybe the guests were wearing better clothes

abstract psychological curiosity in motives, including abnormalities–>russian approach

going in depth for big questions, characters not being introverted

serialization of lengthy works, such as ‘war & peace,’ adds towards creating a broader debate. they become part of the broader debates occurring during their time

some compare the creation of microcosms of russian lit to ‘the wire’

comparing to british office, where they look at the camera at moments of despair but the viewer cannot do anything to help // to embarrasing dostoevsky characters

nabokov disliked dostoevsky for his “bad writing”

dostoevsky had a v diff approach to writing from nabokov: almost got executed literally, then was told he had another five years

that is also why dostoevsky did not pursue inanimate writing, unlike tolstoy (?)

nabokov didn t like music!

neither did dostoevsky !! (probably diff reasons)

saul bellow s ‘dean of december’–>similar urgency in truth-seeking (someone from the audience)

can reading a book be so vivid it appears like a different life?

if yes, it depends on willingness of writers to go to great lengths in creating characters who go too far, embarrass themselves/ are visceral

perhaps a key element that helps bring about the urgent truth-seeking: religion s role for the writers

religion, like their fiction, was trying to explain what goes on beyond the physical

nabokov s direct ancestor was dostoevsky s jailor. weird how he was not willing to cut him any slack, considering

dostoevsky was crowd-pleasing oriented bc he lived off writing

MONEY!!!

February 11th, 2014 / 5:20 pm

The Fiction of New Russian Realism

![]()

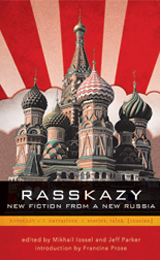

Rasskazy, an anthology of “new fiction from a new Russia” presents a reviewer with an interesting challenge: how to write about these texts as though they had something in common with each other. The book is held together by the assumption that the authors share not only a common language, but that their work is representative of “new Russia” in at least two important ways: in the authors’ political and cultural engagement and in their continuation of “the great Russian literary tradition.” In their preface to the anthology, editors Mikhail Iossel and Jeff Parker frame the texts within the politics of the Putin-era Russia that they see as “turning back the hands of Russia’s sociopolitical clock” and implicate all authors as opposition to this political process. The editors’ ideology in approaching this collection comes across in statements such as: “Russian writing has once again found itself invested with a higher purpose. The writers in today’s Russia derive their sense of relevance from having been adjudged irrelevant by the country’s rulers (i.e., nonthreatening to the latter’s political agenda).”

Rasskazy, an anthology of “new fiction from a new Russia” presents a reviewer with an interesting challenge: how to write about these texts as though they had something in common with each other. The book is held together by the assumption that the authors share not only a common language, but that their work is representative of “new Russia” in at least two important ways: in the authors’ political and cultural engagement and in their continuation of “the great Russian literary tradition.” In their preface to the anthology, editors Mikhail Iossel and Jeff Parker frame the texts within the politics of the Putin-era Russia that they see as “turning back the hands of Russia’s sociopolitical clock” and implicate all authors as opposition to this political process. The editors’ ideology in approaching this collection comes across in statements such as: “Russian writing has once again found itself invested with a higher purpose. The writers in today’s Russia derive their sense of relevance from having been adjudged irrelevant by the country’s rulers (i.e., nonthreatening to the latter’s political agenda).”

September 24th, 2010 / 1:37 pm

Reading Russia: Chapter 1 of Viktor Shklovsky’s Theory of Prose

And so, in order to return sensation to our limbs, in order to make us feel objects, to make a stone feel stony, man has been given the tool of art. The purpose of art, then, is to lead us to a knowledge of a thing through the organ of sight instead of recognition. By “enstranging” objects and complicated form, the device of art makes perception long and “laborious.” The perceptual process in art has a purpose all its own and ought to be extended to the fullest. Art is a means of experiencing the process of creativity. The artifact itself is quite unimportant.

I’m slowly working my way through Viktor Shklovsky’s Theory of Prose (translated by Benjamin Sher and published by Dalkey Archive Press). I’ve read the introduction by Gerald Bruns, the translator’s preface, and the first chapter so far and have been pleased with the result. Especially fascinating to me is this idea of ostraniene (Sher admits to having translated this neologism by coining the word ‘enstrangement’) and how it works in art, or rather prose (fiction, for me). It seems to me that ostraniene is a foundational piece of Shklovsky’s theory; therefore, it’s worth devoting some time to here.

I’m slowly working my way through Viktor Shklovsky’s Theory of Prose (translated by Benjamin Sher and published by Dalkey Archive Press). I’ve read the introduction by Gerald Bruns, the translator’s preface, and the first chapter so far and have been pleased with the result. Especially fascinating to me is this idea of ostraniene (Sher admits to having translated this neologism by coining the word ‘enstrangement’) and how it works in art, or rather prose (fiction, for me). It seems to me that ostraniene is a foundational piece of Shklovsky’s theory; therefore, it’s worth devoting some time to here.

Chapter one, titled ‘Art as Device,’ begins with a discussion of art as an image-based sort of production.

September 11th, 2009 / 7:27 pm

BOMBlog: Russian Avant-Garde

Those who are following my year-long Russian lit journey might be interested to glance over at the BOMBlog, where Kevin Kinsella has an essay about the Russian Avant-Garde, particularly the photos of Aleksandr Rodchenko, whose portraits of Lilya Brik, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Osip Brik have shifted through various meanings/uses: photographic evidence of the threesome’s close friendship, symbols of the Russian Avant-Garde movement, and state propaganda posters.

Those who are following my year-long Russian lit journey might be interested to glance over at the BOMBlog, where Kevin Kinsella has an essay about the Russian Avant-Garde, particularly the photos of Aleksandr Rodchenko, whose portraits of Lilya Brik, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Osip Brik have shifted through various meanings/uses: photographic evidence of the threesome’s close friendship, symbols of the Russian Avant-Garde movement, and state propaganda posters.

Off to Russia

In two hours my wife and I leave for the airport to fly to London and then from London we will fly to Moscow. Then after a few days in Moscow, we will fly to St. Petersburg.

We’ll see if I have any good stories/photos when I get back?

In the meantime, check out Zachary Schomburg’s June posts about his trip to Russia last year.

(via Adam Peterson)

Later.

Reading Russia: One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn

I went through high school without having read One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich. I read other common high school books, such as A Separate Piece, Catcher In The Rye, A Tale of Two Cities, and a few ones that strike me as odd for high school (Ridley Walker?), but never this one.

I went through high school without having read One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich. I read other common high school books, such as A Separate Piece, Catcher In The Rye, A Tale of Two Cities, and a few ones that strike me as odd for high school (Ridley Walker?), but never this one.

I finally read it in January, and I’ve just now got a chance to type some thoughts, which will be very brief, because I did not take notes as I read this one.

Like Night by Elie Wiesel and Survival in Auschwitz by Primo Levi, One Day In The Life tells in rather plain, unadorned language (as far as I can tell through the translation) of how a human copes under massive, institutional cruelty, though in this case Denisovich is ‘fictional.’ I’m assuming most of you are very familiar with this book, so I’m not going to really summarize it or anything: there’s the usual intense description of prison camp procedure, the remarking of odd traditions, the listing of ways one might die, etc. The main character must constantly position himself to survive the day. And what I found fascinating in these books is how the daily routine, the little microcosms of the camps, sometimes gave the prisoners respite. I’m thinking here of how Primo Levi’s background as a chemist helped him receive a work detail as an assistant in a laboratory, thus protecting him from the harsh winter.

May 12th, 2009 / 1:54 am

Reading Russia: We by Yevgeny Zamyatin

We by Yevgeny Zamyatin is the dystopian novel you’ve never read. Or maybe you have read it. I don’t know. I had not heard of it until I found it on a recommended reading list of Russian novels, and then a former student of mine learned of my planned trip to Russia and loaned me his copy.

We by Yevgeny Zamyatin is the dystopian novel you’ve never read. Or maybe you have read it. I don’t know. I had not heard of it until I found it on a recommended reading list of Russian novels, and then a former student of mine learned of my planned trip to Russia and loaned me his copy.

What follows the jump is another post about my ongoing Russian lit reading experience. This post is in two parts: the first considers We‘s place in the world, which I thought I should share because the novel doesn’t seem all that popular or familiar to readers, though that was only my experience; the second part consists of a selection from the book and a quick revisit of Notes from the Underground.

April 27th, 2009 / 1:59 am

Reading Russia: The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov

It’s very hard for me to separate these two books in my mind. Elements of each strike me for their similarity: the characters Prince Myshkin and Alyosha Karamazov, Nastasya Filippovna and Agrafena Svetlova, Parfion Rogozhin and Dimitri Karamazov, Gavrila Ivolgin and Ivan Karamazov; there is some sort of complicated love triangle between everyone; someone is murdered in a gruesome fashion (by knife and by pestle); and so on.

It’s very hard for me to separate these two books in my mind. Elements of each strike me for their similarity: the characters Prince Myshkin and Alyosha Karamazov, Nastasya Filippovna and Agrafena Svetlova, Parfion Rogozhin and Dimitri Karamazov, Gavrila Ivolgin and Ivan Karamazov; there is some sort of complicated love triangle between everyone; someone is murdered in a gruesome fashion (by knife and by pestle); and so on.

The heft of these books encourages me to take them on long journeys, so that I may always have words to read. I want to wear them on my feet and grow two inches taller, because I am only 5’6″ and I read a study somewhere that taller people tend to make more $ in the business world. I want to hollow out these books and store smaller books inside of them and even smaller books inside of those books. These are the kinds of books that make me wish I could escape from writing stories that involve two people saying stupid things about sperm whales to each other. These are the kinds of books that make me miss good storytelling.

April 21st, 2009 / 8:29 pm

Reading Russia: Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground

As you may already know, this summer I’ll be traveling to Russia for a week. Because of that trip, I decided to read as much Russian literature as I could. I even blogged about my plans over at Conversational Reading. But so far, I haven’t read much; it’s taken me longer than I expected just to get through Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov. What follows are some brief thoughts (perhaps too personal?) about Notes; look out for more posts on the next few books. Read on if you’re interested.

As you may already know, this summer I’ll be traveling to Russia for a week. Because of that trip, I decided to read as much Russian literature as I could. I even blogged about my plans over at Conversational Reading. But so far, I haven’t read much; it’s taken me longer than I expected just to get through Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov. What follows are some brief thoughts (perhaps too personal?) about Notes; look out for more posts on the next few books. Read on if you’re interested.

April 17th, 2009 / 1:40 am

Places Where I Read Primo Levi’s If This is a Man

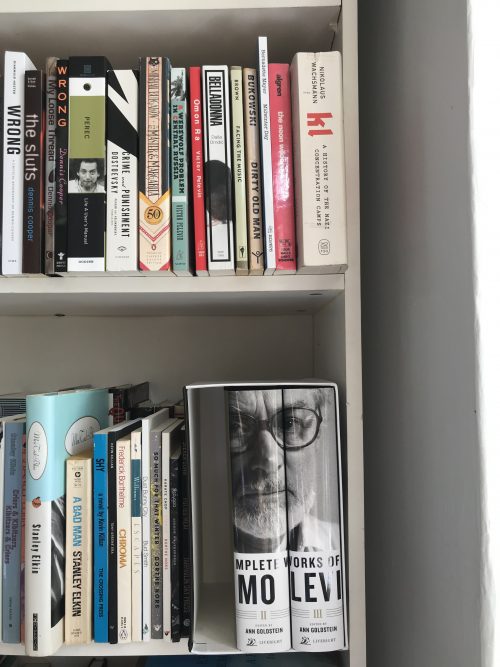

I bought The Complete Works of Primo Levi with unemployment money. It comes in a box and when the spines of the three volumes are put together they form the face of Primo Levi. When I am in my living room I can see Primo Levi and he watches me. We make eye contact. But I took the first volume out of the box and now he is missing a quarter of his face.

* * *

I am reading Levi’s first book, If This Is a Man, a memoir of his experience as an Italian Jew in Auschwitz. When the book was published in America it was given the title Survival in Auschwitz, a title almost as bad as Auschwitz for Dummies.

Put Auschwitz in the title or they won’t know it’s about Auschwitz, an editor must have said.

* * *

My great-bubby, Ethel Belgratsky, fled pogroms in what is now Ukraine long before the Holocaust and she lived in Montreal during the Second World War. But I don’t know what happened to the cousins and other relatives who never left. My Uncle’s wife’s mother survived the camps and fell in love with a Russian soldier. My grandfather—I call him Papa Howard—doesn’t know where our Novaks originate but the legend is that we are Lithuanian Jews. Litvaks. None of this is concrete to me. All of these people I never met swirl around in my head.

* * *

I like this book a lot. It is not a long book. I am reading it slowly because the sentences are rich and unique, simultaneously simple and complex, and the subject matter isn’t something I find myself able to breeze through. Every chapter is about life and death and pain and humiliation and hunger and thirst and hope and hopelessness and language and fear and the random stupidity of evil and innocence and cunning and chance and disease and excrement and chemistry and clothing and bowls and spoons and soup and bread and humor and fatigue and judgement and memory and war and almost no peace.

* * *

I read some of If This Is a Man on the blue couch in the living room in the morning. My back hurts. I don’t like our bed. Sometimes I sleep on this couch when I am sick of the way our bed is treating my back. It is winter and Primo Levi is in a crammed boxcar headed to Auschwitz. The men, women, children, and infants suffer “from thirst and cold.” Finally, after a long journey from Italy to Poland, the train stops. Primo and the woman who has been pressed against him for the entire journey, an acquaintance of his, say to each other “things that are not said among the living.” They say “farewell and it [i]s short; everybody s[ays] farewell to life through his neighbor.” Then the train car doors open and the men and women and children are separated by SS guards. The able-bodied men go one way and as for the women and children and old people, “the night swallow[s] them up, purely and simply.” The book is heavy in my hands. Each volume is a hardcover and Volume I is 747 pages long. IfThis Is a Man is the first book in Volume I and it ends on page 165. I am on page 16 and my eyes are wet after reading about a three-year-old named Emilia who had to be killed because she was a Jewish three-year-old. My hands and arms have to work to keep the book from falling onto my face.

READ MORE >