Writing in Plain Sight: The Author, the Narrator and the Difference (if any)

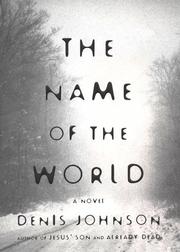

When fiction reading is going well for me, I translate the words into something that’s both fiction and non-. Take the novel The Name of the World by Denis Johnson, which I read recently for the first time. Here’s the first paragraph:

Since my early teens I’ve associated everything to do with college, the “academic life,” with certain images borne toward me, I suppose, from the TV screen, in particular from the films of the 1930s they used to broadcast relentlessly when I was a boy, and especially from a single scene: Fresh-faced young people come in from an autumn night to stand around the fireplace in the home of a beloved professor. I smell the bonfire smoke in their clothes and the professor’s aromatic pipe tobacco, and I feel the general unquestioned sweetness of youth, of autumn, of college—the sweetness of life. Not that I was ever in love with this scene, or even particularly drawn to it. It’s just that I concluded it existed somewhere. My own undergraduate career stretched over six or seven years, interrupted by bouts of work and transfers to a second and then a third institution, and I remember it all as a succession of requirements and endorsements. I didn’t attend the football games. I don’t remember coming across any bonfires. By several of my teachers I was impressed, even awed, and their influence shaped me as much as anything else along the way, but I never had a look inside any of their homes. All this by way of saying it came as a surprise, the gratitude with which I accepted an invitation to teach at a university.

I relate strongly to the narrator, who we learn later is named Michael Reed. The amount of emotional overlap between Michael’s and my life is scary. I too held similar images of academic life, for me perhaps set in the fifties and involving more letterman sweaters, but the same otherwise. Like the narrator, it took me six or seven years to finish college, and involved three transfers. I was also impressed by my teachers, and I also never imagined seeing the insides of their homes. This is exactly what I look for in a novel reading experience, a character who’s as much like me as possible, and telling his—our—story with a compelling, authoritative voice. Telling me, in short, about me.

But at least as important as my strong relationship to the narrator is the strong relationship I feel to the author. I read the above sentences, and I feel like I know the narrator’s shadow figure, Denis Johnson, very well. How can one write of this bucolic college tableau, “Not that I was ever in love with this scene, or even particularly drawn to it,” and not on some level feel the same way? I think of actors, who have to find something relatable in every character they play, even reprehensible ones. Can a writer fake this stuff? If he can’t, then what’s really the difference between Michael Reed and Denis Johnson?

And still there’s a third level in which I feel a deep connection to this work. As a writer myself, I feel a strong professional connection to the author for these perceived overlaps in our histories and psyches. Denis Johnson is a successful—even world-class—writer, and I hope that these emotional/biographical similarities mean that I somehow—despite all evidence to the contrary—am on some kind of path to a literary career. This guy is just like me, and he won the National Book Award! I can’t help but hope, despite my age, lack of comparable publishing success and absence of completed work as riveting as, say, Jesus’ Son, that I am somehow in the same game as Denis Johnson.

So The Name of the World hit me squarely because I relate to the narrator, and the writer, and because I want to succeed like the writer has succeeded. In other words, I’m about as perfect an audience for this novel as there is.

In all my exploration of writers and writing (B.A. in English, M.F.A. in Writing, 25 years of near constant reading and writing outside of class), I’ve rarely heard anyone mention this third, professional angle to readerly empathy. I suspect this is because, back when I was in school, writers still entertained the idea that most of their audience would come from actual readers and not other writers. There were of course “writers’ writers” back then, or those authors who were read almost exclusively by other writers—David Foster Wallace comes to mind. But I still think we were largely in the Saturday Evening Post romance of the reader/writer relationship, that is, educated people sitting down with books and magazines and being sucked in by written pieces. The author Gary Shteyngart gets credited for having said, “The number of people who read serious literature is now exactly equal to the number of people who write it.” Maybe an exaggeration, but probably the healthiest angle from which to come at a literary writing career in 2014.

Despite my deep interest in the writer of The Name of the World, I wouldn’t like the book as much if it were memoir. Imagine if the first sentence of the intro paragraph were “Hi, I’m Denis Johnson,” and “Denis Johnson” replaced “Michael Reed” throughout. I would still be interested in the book, and I’d probably read it and relate to it deeply at points. But I could never fully imagine myself into the narrator’s plight the way I can with the novel The Name of the World. In other words, the memoir The Name of the World would never quite be about me and Denis Johnson the way the novel is. The fiction tag allows Johnson, or any writer, to play both hands: he can utilize a fictional narrator, which allows the reader more leeway to see herself in the character, and he can titillate with suggestions of autobiography, which allows the reader to form empathy with the writer. Somehow these two readerly perspectives aren’t contradictory. The narrator of The Name of the World is both Michael Reed and Denis Johnson, and I’m fine with that.

May 12th, 2014 / 10:00 am

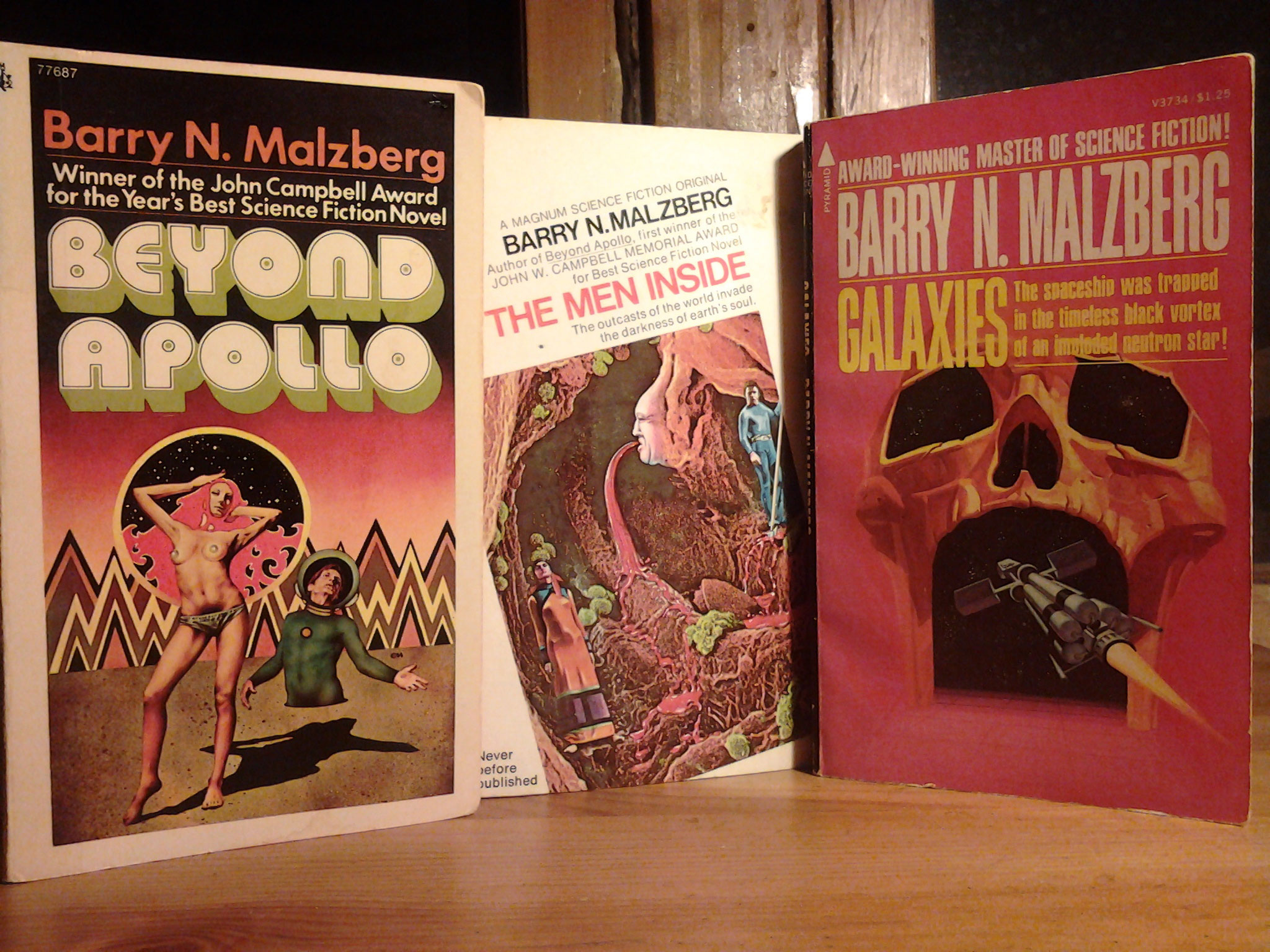

25 Points: 3 Novels by Barry N. Malzberg (Beyond Apollo, The Men Inside, & Galaxies)

Beyond Apollo | 1972, Random House | 156 pages

The Men Inside | 1973, Prestige Books | 175 pages

Galaxies | 1975, Pyramid Books | 128 pages

(Note: all three of these books are out of print, but cheap used copies can be found. In Chicago, I bought Beyond Apollo for $2.95 at Myopic Books (in Wicker Park) and The Men Inside for $3 at Bucket O’ Blood Books and Records (Logan Square). Galaxies I purchased used through Amazon for $1.25 + s/h.)

1. On 15 August 2011, my pal Jeremy M. Davies emailed me and said that I should look for a book called Galaxies by Barry N. Malzberg because it was “seriously beyond belief.”

I’m ashamed to say it took me until earlier this year to pick up a copy and read it. However, once I got started, I finished it under 24 hours.

2. Barry N. Malzberg was born in 1939. Since 1968, he’s written at least 66 books, if not more. (He’s worked under ten different names that I know of, which complicates compiling a full list.) Dozens of them are science-fiction novels—at least in theory. He’s also written story collections, essay collections, movie novelizations, crime novels, and pornography.

3. Galaxies (1975) at first glance tells the story of a young astronaut, Lena Thomas, the sole crew member of the spaceship Skipstone. Her cargo is an immense tank of goo filled with 515 human corpses. It’s the year 3902 and a person can pay to have his/her body ferried into space after death in the hopes that cosmic radiation will revive them.

Midway through the voyage, the Skipstone falls into a black hole, and the majority of the novel’s plot deals with Lena’s attempt to escape the ensuing hallucinatory free fall. During that timeless time she repeatedly dies and is reborn, recalls her lover John, consults with cyborg engineers, and communes with the dead, who have psychically reawakened.

But that’s not really what Galaxies is about.

4. Rather, Galaxies is a work of metafiction, concerned with its own creation, and presented as Malzberg’s notes on how he would write the novel Galaxies, if only he could. (He maintains that the novel is impossible to complete with present knowledge.) As such, most scenes are outlined rather than dramatically depicted. For instance, Chapter 29 begins:

And here could run yet another moody flashback concerning Lena’s relationship with John, dropped in to provide color and poignance, augmenting the mood of despair. Long sexual passages here could alternate with painful streams of consciousness in the present. Sex and space, orgasm and isolation could run counterpoint, and the author’s gifts for irony, which are not modest, would be exhibited to their fullest range. Also, in the traditions of modern science fiction, the sex scenes could be quite titillating, render the novel some extraliterary interest. A construct like this could use all the extraliterary interest it could get.

But even that’s not really what Galaxies is about.

6. Rather, Galaxies is about what science-fiction should look like in the year 1975. Malzberg is surveying contemporary literature and asking: How should science-fiction respond to the then-recent literary experiments of John Cheever, John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Joyce Carol Oates, Philip Roth, and others?

7. I’m not making this up. On page 48 Malzberg writes:

For instance, as the ship falls, there could be some elaboration on the suggestion that neutron stars might be pulsars which would be most intriguing, if the reader has not been intrigued sufficiently by the notion that all of “life” as we understand it when we glimpse the heavens may be merely an incidental by-product of the cycle of neutron stars.

So there, Cheever, Barth, Barthelme, Oates. What in the collected works would touch that for angst?

8. Malzberg calls those authors out again on page 85:

“Madness,” Lena says, shaking her head, “that’s utter madness,” but the author, busily pulling the handles of this little dumb show, sweating behind the canvas, casting a nearsighted, astigmatic eye every now and then through the cardboard of the set to see whether the audience is paying attention, how the audience is taking all of this, is thinking take that Barth, Barthelme, Roth, or Oates! Pace Bellow and Malamud, and may your Guggenheims multiply, but what have any of you or those unnamed created to compare with this?

9. If I haven’t convinced you yet to spend $2–3 on a used copy of Galaxies, you might as well quit reading now.

April 1st, 2013 / 8:01 am

First Sentences or Paragraphs #3: Philip Roth Edition

[series note: This post is the third of five, in a week-long series examining first sentences or paragraphs. It’s not my intention to be prescriptive about what kinds of first sentences writers ought to be writing. Instead, I hope to simply take a look at five sets of first sentences for the purpose of thinking about how they introduce the reader to the story or novel to which they belong. I plan to post them without commentary, as one might post a photograph or painting, and open up the comment threads to your observations as readers. Some questions that interest me and might interest you include: 1. How is the first sentence (or paragraph — I’ll include some of those, too, since some first sentences require the next few sentences to even be available for this kind of analysis) interesting or not interesting on grounds of language? 2. Does the first sentence introduce any particular (or general feeling of) trouble or conflict or dissonance or tension into the story that makes the reader want to keep reading? 3. Does the first sentence do anything to immerse the reader in the donnee, the ground rules, the world of the story, those orienting questions such as who speaks, when and where are we in space and time, etc.? 4. Since the first sentence, in the wild, doesn’t exist in the contextless manner in which I’ve presented these, in what kinds of ways does examining them like this create false ideas about the uses and functions of first sentences? What kinds of things ought first sentences be doing? What kinds of things do first sentences not do often enough? (It seems likely to me that you will have competing ideas about first sentences. Please offer them here. Every idea or observation gets our good attention.) The sentence/paragraph sets we’ve been or will be observing: 1. first sentences from Mary Miller’s Big World; 2. first sentences from physically large novels; 3. the first sentences from every book written by Philip Roth; 4. first sentences from the Norton Anthology of Short Fiction; 5. first sentences from Best European Fiction 2010.]

The first time I saw Brenda she asked me to hold her glasses.

– Goodbye, Columbus

Dear Gabe, The drugs help me bend my fingers around a pen. READ MORE >

Dept. of Arbitraryish Statistics: Three Variations on Three-Act Structure Edition

Coetzee, J.M. Disgrace. New York: Viking, 1999.

Acts: 3.

Chapters: 24.

Chapters per Act: 8.

Pages per Chapter: 8-10. READ MORE >

November 22nd, 2010 / 2:05 am

Variations on Hating Part 2! The Young Philip Roth Rebels

I had- and still have, but that’s another post- a huge crush on Philip Roth. Look how hot he was. In an earlier brief post (click here), I touched on a certain artist’s need to embarrass herself. I often feel the same. I think Roth did, too. Perhaps it’s a youthful impulse. Regardless, I believe Roth has three masterpieces (One which is actually four books): Zuckerman Bound (which consists of The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman Unbound, The Anatomy Lesson and The Prague Orgy ), Sabbath’s Theater and American Pastoral. (Oh, And possibly The Counterlife goes in there too.) READ MORE >

I had- and still have, but that’s another post- a huge crush on Philip Roth. Look how hot he was. In an earlier brief post (click here), I touched on a certain artist’s need to embarrass herself. I often feel the same. I think Roth did, too. Perhaps it’s a youthful impulse. Regardless, I believe Roth has three masterpieces (One which is actually four books): Zuckerman Bound (which consists of The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman Unbound, The Anatomy Lesson and The Prague Orgy ), Sabbath’s Theater and American Pastoral. (Oh, And possibly The Counterlife goes in there too.) READ MORE >

The ecstasy of a faint outdoor wind: A photo essay by Philip Roth

Hi, I’m Philip Roth, the author American Pastoral and other books without so much foliage. I love the smell of fresh cut grass and foreskin. But hey, enough with the Jewish jokes. Whenever the camera crew comes to do a profile on me, I say “Hey, I have an idea — it would be nice if we went outside.”

I’m thinking. I’m thinking about America and the plight of the ‘other.’ I’m thinking about a waspy girl I once wanted to make love to. I’m thinking of that protestant ass. I’m thinking of my shopping list: eggs, broccoli, extra virgin olive oil, national book award, toilet paper. God I love being outside at or around dusk.

I’m thinking. I’m thinking about America and the plight of the ‘other.’ I’m thinking about a waspy girl I once wanted to make love to. I’m thinking of that protestant ass. I’m thinking of my shopping list: eggs, broccoli, extra virgin olive oil, national book award, toilet paper. God I love being outside at or around dusk.

Viewer Mail!

| from | |||

| to | |||

| date | |||

| subject | |||

| mailed-by | |||

Hello Justin Taylor,

-Mark Baumer

—

www.thievesjargon.com

www.everydayyeah.com

Gee, that was random.

********BONUS********* JUSTIN TAYLOR REPLIES:

| rom | |||

| to | |||

| date | |||

| subject | |||

| mailed-by | |||

Hi, Mark, thanks for writing. I don’t really know what to make of your letter. To be honest, it doesn’t seem like it should have been addressed to me. It’s not exactly about any of the things I wrote about in my recent blog post, which itself was rather explicit about being somewhat predicated by, but hardly “about,” Matt DiGangi and Thieves Jargon–two entities about which I know very little, and not for lack of opportunity either.

I’m sorry that Matt has to edit boring textbooks. We must, all of us, do something. For example, I have to think of lesson plans and commute to New Jersey twice a week to teach my class, and then I have to grade my students’ papers. Let me tell you, brother, it’s no walk in the park, although I do get to walk through campus, which has many park-like qualities. Also, sometimes the students write things that are very funny. Typically, they have not done so on purpose.

Speaking of which, I have no idea what “when the internet was still good” means, but then I’m not the one who said it. Since you’re the one who said it, it is discomforting to know that you don’t know what it means either. Do you often make declarations incomprehensible even to yourself and then send them off in personal letters to strangers?

Personally, I think shoelaces both got really lame in the mid-90s, but they seem to have really re-emerged during the last year or two, totally transformed and ready to assert their relevance–even necessity, perhaps–to the culture. I can’t wait to see what happens with shoelaces next.

In closing, I wish that I could promise to keep your secret about the simplicity of your cake recipe from Jimmy, but the fact of the matter is that I’m almost certainly going to post your letter and my response (that is, this letter which I’m writing right now) on HTMLGiant later this afternoon, or possibly even this morning, so I guess he’ll probably learn the truth that way.

JT

************DOUBLE YOUR BONUS*********

M. BAUMER REPLIES TO THE REPLY:

| from |  M. Baumer M. Baumer |

||

| to |  Justin Taylor Justin Taylor |

||

| date |  Thu, Dec 4, 2008 at 12:52 PM Thu, Dec 4, 2008 at 12:52 PM |

||

| subject |  Re: a note from thieves jargon Re: a note from thieves jargon |

||

| mailed-by |  gmail.com gmail.com |

||

Hey Justin,

I give you permission to post my email without my permission.

Please include this:

I also want to say something about BB that makes fun of the way he gets off or something, but I am not very good at shit talking.

Justin, I think you want me to kill myself. ‘Shoelaces’ was my self-termination code word when I was created as a sad pot of soup on the back left burner. Then some family ate me.

I honestly think lots of people would consider being gay with BB’s blogspot account. I guess this is a compliment. Sometimes I worry about saying anything bad about BB and any other expert bloggers because in the back of my head I think, “If they kill themselves someone in the future will read this comment of me calling them a ‘shitfuck’ and then they’ll google my name and find my address and come to my house via google maps and dump un-erasable spam on my front lawn and my wife will say, ‘how could you say that?’ and then stop talking to me over gchat and i’ll marriage will be over.”

Oh well.

To Blake

“You’re a shitfuck. Don’t kill yourself.”

Are we having a feud now? About what?