I am drinking Juicy Juice and scouring the Internet for action figures based on my favorite childhood comics & cartoon franchises while complaining about—nay, BEMOANING—capitalism’s failure to deliver to me precisely what I want

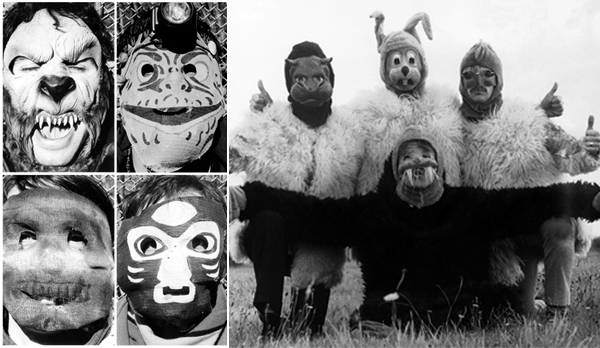

Four or five years ago, for my birthday, I bought myself Neca’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles figures—the awesome ones based on the original Kevin Eastman & Peter Laird’s original comics, like so:

They are so utterly badass. They all have red bandanas, for one thing, and they also have tails, which got clipped from the later TV cartoon versions because they looked like—penises, I guess.

As you can readily see, I am a proud owner of these figures:

Notes While Reading “Cityscapes” Anthology (Editor: Jacob Steinberg)

Cityscapes / Jacob Steinberg Prologue

Cityscapes was edited by Jacob Steinberg. Jacob goes to NYU (does he still go to NYU?). I remember he used to bro-down with Spencer Madsen and one time they did a Ustream from the beach in Florida or something. I’ve been in many Tinychats with Jacob. I like him.

Jacob mentions Julio Cortazar in his prologue. We’re both fans of Cortazar and of Clarice Lispector, not that those are rare people to be fans of, but I feel as if we’ve e-bonded over being into those authors. Jacob asked me to be in this but my piece wasn’t really about Chicago particularly. Took place on the internet.

Animal Cooperative

Two or so years ago I delusionally signed up for OkCupid, uploaded the one photo in which I did not look like a turtle from an oncology ward, scoured my matches for Caucasian girls between the ages of 22-25 who liked Animal Collective, and messaged them with the intention of jumping into an aurally heightened relationship immediately after some indiscretionary coitus. I was rebounding hard, slowly going soft. I didn’t like Animal Collective, but somehow had it in my mind that I would like a girl who did: precociously artsy, preciously depressed, and pretentiously insane. The lie I told myself of who would make me happy was the masochistic prophecy of who could make me miserable. “Cool, I like Animal Collective too,” the douche in me wrote. Not one of them wrote back. My favorite track off The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour (1967), is George Harrison’s “Blue Jay Way,” a dead end road in the LA hills. He’d play a part, then play it backwards, then learn to play the backwards version, record it, then play that backwards, so that the orientation was forward again. Its dissonance eerily familiar. One cannot go backwards in time, only melody. John famously claimed he was the walrus through implicated tusks, churning away at the meta. I sign up for Match dot cum, the co-op of lonelies, my credit card number longer than my patience for the questionnaire. I end up surrounded by sweaty kids getting epileptic to four bros on stage, Δ9-THC’s trail ribboning in the air, trying to be somebody, a person who someone else would write back to. All the world’s a stage, covered in Miller lite. Someone smiles, my mask shows nothing.

Cosmo by Spencer Gordon

Cosmo

Cosmo

by Spencer Gordon

Coach House Books, 2012

218 pages / $18.95 Buy from Coach House

In his much-cited 1993 essay E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction, David Foster Wallace bemoans what he then saw as the rise of a mode of hyper-referential, pop/junk-culture-splattered fiction, one where “velocity and vividness—the wow—replace the literary hmm of actual development,” that in lieu of plot or character favours moods, the “antic anxiety, the over-stimulated stasis of too many choices and no chooser’s manual, irreverent brashness toward televisual reality,” and—like television or other similarly clipped fields of entertainment (Wallace, writing in the nineties, naturally focuses on TV, but his arguments are easily transposed to today’s even vaster glut) operate in images, rather than quaint notions of emotionality. In pursuit of surface realism, there is risk of forsaking heaviness, or timelessness, or truth.

As in every era, today’s crankers-out of culture face this squirrely dilemma of realism: just how far the boundaries of mundane contemporaneity can or should extend, and how useful any parameters therein might be delineated—that is, the question of how realism should be defined right now, and whether such a classification matters, or even exists. If an author adopts or mangles forms anchored explicitly in “today,” is such a thing inherently parodic, or just being true to the times? It is certainly possible to write fiction about Facebook (and, oh, it is done), but do we find this acceptable?

Spencer Gordon’s new short story collection Cosmo enthusiastically elbows its way into that mosh pit of a question with equal measures vigour and charm. Though offering a gaudy all-you-can-eat spread of pop/junk cultural references, the book selects its menu wisely, hitting both the salad bar and the sundae counter in equal measures, as it were. Gordon is unafraid, for example, to hinge a lengthy passage around the single word “YouTube”—describing how, for one character in distress, the word rings “like black magic, a sinister open sesame to some sealed chamber inside her”—and it’s, for the most part, not only convincing, but stirring.

November 9th, 2012 / 12:00 pm

“Sirk has said you can’t make films about something, you can only make films with something — with people, with light, with flowers, with mirrors, with blood, with all these crazy things that make it worthwhile.”

— Fassbinder

That’s how I feel with poetry.

25 Points: Thunderbird

Thunderbird

Thunderbird

by Dorothea Lasky

Wave Books, 2012

107 pages / $16.00 buy from Wave Books

1. Wave Books made a hardcover edition of this book with a pink cover but it is sold out on their website.

2. The only time I’ve seen Dorothea Lasky read was at last year’s AWP (Chicago) where she read in a theater and everyone clapped when she read and thought she was great (I also thought this).

3. After the whole reading was over there was a dance party and Dorothea Lasky was dancing nearby and I told my friend Chris that I liked her poems and I think she heard me and I turned to her and said something like, “Sorry, I’m talking you like you aren’t in the room or something.” She just smiled because she is a nice human being and poet.

4. The title of the book and all the poem titles are typed in what seems like a medieval font–like something one would see on stained glass windows.

5. “I Like Weird Ass Hippies” is probably the funniest poem title in the book (she read it AWP).

6. “I make hell to live in / I make hell”

7. “The world doesn’t care” is a poem that tells the truth and is not complicated; everyone should read it.

8. I am listening to Allo, Darlin’ and writing this and I feel this band is a good soundtrack to Dorothea Lasky’s poems.

9. “Let’s sit in a sea of flames / And I will never put the fire / Out of you” is something I wish a woman will tell me someday when she is talking to me, not reading the poem in which Dorothea Lasky writes it.

10. A person says, “Is this America?” in a poem titled “The Room” and I think lots of poets ask this important question. READ MORE >

November 8th, 2012 / 1:01 pm

I still work, motherfucker–New Sam Pink!

Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading this week is an excerpt from Sam Pink‘s forthcoming novel, Rontel, which is coming Valentine’s Day 2013 in print form from Lazy Fascist Press (kudos to Cameron Pierce!), as well as in a digital edition via Electric Literature. EL has also posted an animation of one of the sentences:

I found the excerpt hilarious and enjoyable and good. Sam is one of my favorite authors. I assume a lot of people who come to this site already love Sam Pink or suck, but if you don’t know him, he is a very clever author, darkly comic with some other thing going on.

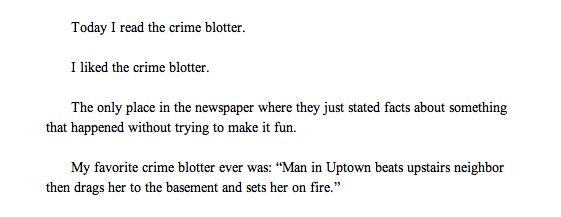

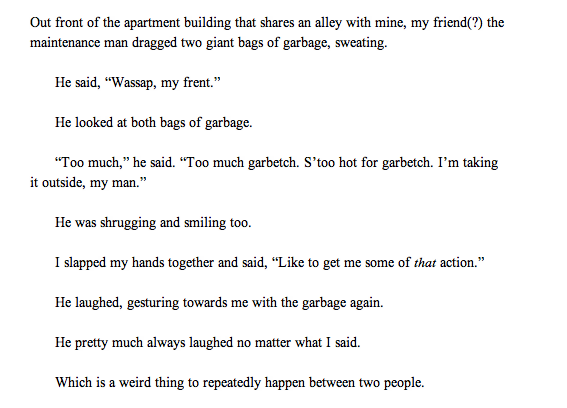

Some excerpts from the excerpt:

And also:

Viva Sam Pink!

25 Points: The Book of Monelle

The Book of Monelle

The Book of Monelle

by Marcel Schwob

translated by Kit Schluter

Wakefield Press, 2012

136 pages / $12.95 buy from Wakefield Press or Amazon

1. Let’s just start with the fact that this book made me cry. It’s an utterly heartbreaking book, beautiful in the torment and suffering that is manifested through its words. Though Monelle instructs, “Words are words while they are spoken. / Unspoken words are dead and beget the plague. / Listen to my spoken words, and act not according to the words I write,” these written words are the only spectral trace we have left of her.

2. I first heard about the new translation of this significant work at Harriet.

3. The synopsis of the book reads: When Marcel Schwob published The Book of Monelle in French in 1894, it immediately became the unofficial bible of the French symbolist movement, admired by such contemporaries as Stephane Mallarmé, Alfred Jarry, and André Gide. A carefully woven assemblage of legends, aphorisms, fairy tales, and nihilistic philosophy, it remains a deeply enigmatic and haunting work over a century later, a gathering of literary and personal ruins written in a style that evokes both the Brothers Grimm and Friedrich Nietzsche. The Book of Monelle was the fruit of Schwob’s intense emotional suffering over the loss of his love, a “girl of the streets” named Louise, whom he had befriended in 1891 and who succumbed to tuberculosis two years later. Transforming her into Monelle, the innocent prophet of destruction, Schwob tells the stories of her various sisters: girls succumbing to disillusion, caught between the misleading world of childlike fantasy and the bitter world of reality. This new translation reintroduces a true fin-de-siècle masterpiece into English.

4. The Book of Monelle is a book of words, like the Bible, these words may transcend its physical pages. In its biblical and prophetic tone, Monelle, perhaps herself a prophet, speaks of the beginning: “And Monelle said again: I shall speak to you of young prostitutes, and you shall know the beginning.”

5. If Monelle is a prophet, she is utterly of the present, of the moment, and of silence, because in life and suffering everything becomes a mirror to one’s suffering, and because in death there is only silence, but there is also the hope of forgetting.

6. Monelle instructs: “Do not remember, and do not predict.”

7. The translator gives two possible ways to interpret the name Monelle. First, the French translation that roughly translates into “My-her,” which implicates a strange hope for possession. Indeed, the narrator (whom we take to be Marcel’s tortured self) says, “And as I looked over the plain, I saw the sisters of Monelle rising.” Because every “her” is Monelle. And Monelle is every her. And yet, Monelle is of the past and infinitely elusive.

8. Monelle, its prefix derived from monos, then also implies a numeric singularity. Monelle is now and always alone. Schluter, in a footnote to his afterword, describes, “The infinite solitude that draws the narrator toward her is the very force that must ultimately repel him. In the end, no matter how we attempt to grasp her character, her name should be the first clue that Monelle will fade into abstraction in the fashion of a mirage or a dream recalled upon waking.”

9. Monelle speaks: “…for it is necessary that you lose me before you find me again. And if you find me again, I shall elude you once more. / For I am she who is alone.”

10. And then: “Because I am alone, you shall give me the name Monelle. But you shall imagine that I have every other name.” (Louise, Louvette, Lilly, Bargette…) READ MORE >

November 7th, 2012 / 1:01 pm

DEEP DIVE and CEO ONBOARDING

.jpg)

Image by BC (see below in post for further detail)

From the soon-to-be-updated website of my current employer (modified):

BRAND COMMITMENT™

How do you maximize it for your brand?

What does every marketer want? A consumer who chooses their brand, spends more, and stays loyal. HTML Giant understands this consumer and can help shape their commitment as never before.

That’s because we see the purchase as a journey. Our role: to deliver communications that address the consumer’s needs and influence them every step of the way. LEARN MORE >

An Interview with Tim Roberts, Co-Founder of Counterpath in Denver

I’ve been thinking a lot over the last year about how to nurture innovative writing communities and build structures to support those communities in places where they don’t exist, or where the existing structures are rickety or shoddy. About ways to create horizontal networks of writers interested in dialogue and exchange about art and writing outside of a university context. Maybe it’s because I’ve spent too many hours at readings with authors aiming for the NYC big leagues and elbowing each other for position. Too many evenings listening to the same “good story” or “good poem” lectures. Disappointed and often frustrated by the lack of innovative lit/art endeavors outside of a handful of big cities (and smaller centers), I’ve been looking for models for building innovative / small press / interdisciplinary writing communities in all the places we live.

As I set out to look for different examples, one kept coming up: Tim Roberts and Julie Carr’s work to build Counterpath in Denver, Colorado. Counterpath combines so many things: a press, a bookstore, a gallery, a performance space; their focus on the work of writers and artists who are driven to make “linguistic and visual interventions in contemporary global culture” seems spot-on. I am particularly drawn to Counterpath because their definition of what is “new” seems broad and because they are explicitly interested in work from groups often under-recognized in the experimental literary universe: people of color, women, queers. And their list of readings and events made me oh-so-excited: CA Conrad, Rodrigo Toscano, giovanni singleton, Lisa Robertson, Eleni Sikelianos. They’ve collaborated on events with Ugly Duckling Presse and Coffee House Press. I wondered how they did it all, how it all started and wanted to see if there was something I could learn from their experiences. Of course, being in the experimental hotbed of the Denver/Boulder area makes their job a bit easier, but I still wondered how they’d done it. There’s a great interview by Noah Eli Gordon with Julie Carr on the Volta that addresses some of these questions, but I still had more questions when I finished reading it.

So I sent Tim Roberts at Counterpath an email to see if he could give more details about the kind of work they’re doing. This interview is the result. Enjoy.

JP: How did you and Julie Carr begin Counterpath? Why and when? Was it originally a press or a space or a bookstore? Which came first? How did the other pieces develop over time?

JP: How did you and Julie Carr begin Counterpath? Why and when? Was it originally a press or a space or a bookstore? Which came first? How did the other pieces develop over time?

TR: We were living in Oakland, CA, when we started the press, in January of 2006. Julie was finishing a Ph.D. in English at UC Berkeley and I was working in book production at Stanford University Press. Both of us were doing a lot of writing, and then at that point I thought I could deal with most of what was necessary in terms of making the books, including design. The press project itself kind of just came to us and seemed like a natural progression of what we were already doing. We thought it might be useful in two distinct ways, in that it was a project grounded in a broad concept of writing itself, picking up from writers like Blanchot—not necessarily connected to a book, or ink on paper—and that responded to a sense of I guess political hopelessness when the US actually re-elected George W. Bush in 2004.