[in Just-]

BY E. E. CUMMINGS

in Just-

spring when the world is mud-

luscious the little

lame balloonman

whistles far and wee

and eddieandbill come

running from marbles and

piracies and it’s

spring

when the world is puddle-wonderful

the queer

old balloonman whistles

far and wee

and bettyandisbel come dancing

from hop-scotch and jump-rope and

it’s

spring

and

the

goat-footed

balloonMan whistles

far

and

wee

On Violence & Red Tales: An Interview with Susana Medina

I met Susana Medina at the inaugural reading of Book Works’ Semina series in June 2008. Her struggle with deafness and affection for Borges made her immediately endearing. Between shots of whisky and glasses of Haut-Medoc, we talked. Chitchat mainly about films and books, but somehow the talk became serious and autobiographical.

Born of a Spanish father and a German mother of Czech origin, she grew up in Valencia, Spain. Her short film Bunuel’s Philosophical Toys, deconstructs the instances of fetishism in the films of Luis Bunuel. Over the years I’ve come to believe that the gap between what Medina has accomplished in her doctoral thesis on Borges, and what her mainstream colleagues have passed off as literary theory, exposes academic discourse for what it is — an imaginary labyrinth without beginning or end that presupposes its own epistemological superiority.

This interview, started March 2011, has been in the making for nearly two years. I spoke with Susana off and on via Facebook.

***

Maxi Kim: Stewart Home recently described your new book RED TALES as “a total shock to mummy porn fans – E. L. James meets J. G. Ballard! Makes both writing and BDSM dangerous once again.” I personally found it much more readable and theoretically latent than much of what passes today for Feminist writing, much more so than even Kate Zambreno’s Heroines. How did this project come to be? What are its origins?

Maxi Kim: Stewart Home recently described your new book RED TALES as “a total shock to mummy porn fans – E. L. James meets J. G. Ballard! Makes both writing and BDSM dangerous once again.” I personally found it much more readable and theoretically latent than much of what passes today for Feminist writing, much more so than even Kate Zambreno’s Heroines. How did this project come to be? What are its origins?

Susana Medina: I like your way of putting it, ‘theoretically latent.’ Red Tales came about through a cluster of concerns. I was interested in fluid sexualities, gender, androgyny, the irrational, compulsions. All the stories are narrated by wayward female narrators. To articulate a defiant female gaze was important for me. In a way, looking at the female nude in Art History, made me want to make all these women speak back. So maybe I became a ventriloquist for these sensual women who seemed so quiet. It was also a reconciliation with narrative, as my first novel, a fragmentary anti-novel, had as its point of departure the most minimalist Beckett. My interest in poetic fragments remained and I intertwined it with fast-moving narrative, so I suppose there is this newly found pleasure in narrative, with the fragment as counterpoint and vessel for interiority, as well as for the fragmentary realities we live. All the stories are conceived as spaces, like art installations. The image was central to all the narratives. I was really interested in American female artists like Cindy Sherman, Jenny Holzer, Kruger, the vanished Cady Noland, in subjectivity and identity as fluid entities… Thank you about the Kate Zambreno’s Heroines reference, which I googled straight away. Like I googled E.L. James when I came across Stewart Home’s blurb, which I thought was nicely confusing. By the way, I hadn’t read JG Ballard at the time –he was later to become one of my favourite writers-, but the connection is there, in terms of a shared interest in the psychopathology of everyday life.

MK: What do you make of Marie Calloway?

SM: I don’t know her. Who is she? Interesting?

MK: Interesting? It depends on who you ask. Like you, she’s interested in fluid sexualities, gender, compulsions, articulating something that approaches a defiant female gaze. She has put out public nude photos of herself with texts that overlap; there may be a parallel here with your project of looking at the female nude in Art History. I am reminded of that last scene in Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009) when all the wayward anonymous females climb up the hill to presumably kill Willem Dafoe.

SM: Googled her and printed an article, but still haven’t quite woken up. She sounds interesting, like Chris Kraus. You’ve worked with her, haven’t you? Or related? Cousins?

Experimental fiction as genre and as principle

A few years ago at Big Other I wrote a post entitled “Experimental Art as Genre and as Principle.” That distinction has been on my mind as of late, so I thought I’d revisit the argument. My basic argument then and now was that I see two different ways in which experimental art is commonly defined.

By principle I mean that the artist is committed to making art that’s different from what other artists are making—so much so that others often don’t even believe that it is art. As contemporary examples I’m fond of citing Tao Lin and Kenneth Goldsmith because I still hear people complaining that those two men aren’t real artists—that they’re somehow pulling a fast one on all their fans. (Someday I’ll explore this idea. How exactly does one perform a con via art? Perhaps it really is possible. Until then, I’ll propose that one indication of experimental art is that others disregard it as a hoax.) Tao visited my school one month ago, and after his presentation some folks there expressed concern, their brows deeply furrowed, that he was a Legitimate Artist—so this does still happen. (For evidence of Goldsmith’s supposed fakery, keep reading.)

Eventually, I bet, the doubts regarding Lin and Goldsmith will fall by the wayside. Things change. And it’s precisely because things change that the principle of experimentation must keep moving. The avant-garde, if there is one, must stay avant.

That’s only one way of looking at it, however. Experimental art becomes genre when particular experimental techniques become canonical and widely disseminated and practiced. The experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, during the 1960s, affixed blades of grass and moth wings to film emulsion, and scratched the emulsion, and painted on it, then printed and projected the results. Here is one example and here is another example. And here is a third; his films are beautiful and I love them. (The image atop left hails from Mothlight.) Today, countless film students also love Brakhage’s work, and use the methods he popularized to make projects that they send off to experimental film festivals. (Or at least they did this during the 90s, when I attended such festivals; I may be out of touch.)

Those films, I’d argue, while potentially beautiful and interesting, are not necessarily experimental films. As far as the principle of experimentation goes, those students had might as well be imitating Hitchcock.

The Brothers Tsarnaev

While it may seem relevant that Chechnya is auspiciously sandwiched between Russia and the Middle East — exhuming the dormant winds of the Cold War, and the current conflict with Islamic extremism — the Tsarnaev brothers, regardless of how perceived their exile was, acted as Americans; that is, with a kind of free volition this country violently preserves. To simply call them assholes is somehow to dishonor their victims, many of them now amputees whose incomplete image in the mirror every morning will remind them forever of the blast, whose unexplained birth out of nowhere does well to implicate the universe itself. Time will tell how politically motivated this act was — though one doesn’t imagine our young Dzhokhar being the most cooperative, or coherent — hence categorized into either the ideological camp of Ted Kaczynski/Tim McVeigh, or the, sadly, more senseless camp of Columbine/Sandyhook, whose executors are getting younger and younger, and better armed.

While it may seem relevant that Chechnya is auspiciously sandwiched between Russia and the Middle East — exhuming the dormant winds of the Cold War, and the current conflict with Islamic extremism — the Tsarnaev brothers, regardless of how perceived their exile was, acted as Americans; that is, with a kind of free volition this country violently preserves. To simply call them assholes is somehow to dishonor their victims, many of them now amputees whose incomplete image in the mirror every morning will remind them forever of the blast, whose unexplained birth out of nowhere does well to implicate the universe itself. Time will tell how politically motivated this act was — though one doesn’t imagine our young Dzhokhar being the most cooperative, or coherent — hence categorized into either the ideological camp of Ted Kaczynski/Tim McVeigh, or the, sadly, more senseless camp of Columbine/Sandyhook, whose executors are getting younger and younger, and better armed.

David Remnick’s piece (from which this illustration and title is unabashedly taken) in the New Yorker is vulnerably sympathetic to the Tsarnaev family, a liberal impulse which is needed, should one brave the harsher waters of the more “patriotic” sentiment i.e. that we should just bomb “them,” whoever they are (just when you thought the postmodern “Other” was dead). That a white male has taken the throne of the Other may launch us into a new era. Not colored, or queer, or part of some thesis, mush less exotic, he is simply another one of the ever expanding “us” lost in the fold of America, whose race is ostensibly raceless, and whose nationality is a slow and steady reduction of endless immigrations. The idea is rather genius. A country for all, though it often seems like we’ve stopped earning this.

Not since the Revolutionary War — with the exception of Pearl Harbor and 9/11, both quickly mythologized, as if to eagerly render them irrelevant — has foreign conflict breached American soil. Truman’s Hiroshima and Bush’s Afghanistan were respective responses, the former’s flattening sadly more effective. War for us is cordoned off as an abstraction of what happens “over there,” bestowing the general populace a bloodless, though vehement, discourse about its many possible meaning(s) from behind televisions and computers. The Boston explosions simultaneously remind us of two somewhat contradictory things: that there will always be insane, strangely entitled, people (usually white men, or boys) who kill for no reason at all, pointing at in inward pathos; or, more formidably, that a spreading global war, whose disenfranchised have less and less to live for, can always permeate our borders. The easy allusions to Syria or Gaza, frankly, scare the shit out of me, and I think all of us. As for the Tsarnaev brothers (one notes the eerie invocation of the Karamozov brothers), their patricide may be indirectly directed at our founding fathers: brave, violent, and tired men, who likewise came to America to escape a troublesome place.

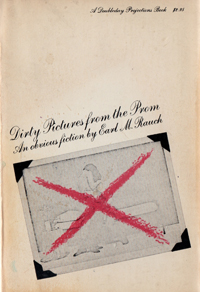

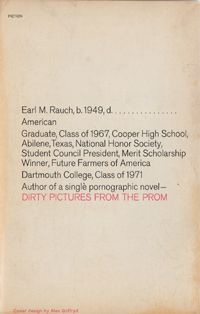

Needing Earl M. Rauch

I discovered Earl M. Rauch’s Dirty Pictures from the Prom on a miserable snowy day this January (2013). As is occasionally the case, I decided to spend said miserable snowy day inside as much as possible—it was a Friday, and after finishing up the day’s classes I wandered over to an antique store in Eau Claire, Wisconsin; a place not known exclusively for its cultural presence (Bon Iver lives here, I guess, some fantastic sauce is made here at Silver Springs, and before dying in a plane crash several days later Ritchie Valens, Buddy Holly, and J.P ‘The Big Bopper’ Richardson played here at a building that’s now defunct). This antique store is massive, and awhile ago I used to come here and collect old issues of Esquire with pieces by Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and the like, as well as old paperbacks I’d never heard of. This particular day I already held two Iris Murdoch hardcovers before looking at a shelf on my way out and seeing a spine that read in a florid cursive ‘Dirty Pictures from the Prom Earl M. Rauch Doubleday’ and already having a copy of Under the Net at home I still had yet to read, I dropped the Murdoch books immediately and picked up this strange text.

While in the store I looked up Earl M. Rauch and discovered the book for sale online for prices seldom lower than 100 USD; this made me want to buy it. He was also a largely unknown person who apparently wrote this—his magnum opus, though not his only contribution to mankind’s literary heritage (more on that momentarily)–when he was only nineteen years old; that, plus the heft of this obviously well-conceived novel, made me want to buy it even more. Then further reading in various biographical pieces about Rauch and his prodigious fascination with writers like Pynchon, made me decide that this was the only book I’d ever truly need and that I’d spend the weekend doing nothing but reading it from cover to cover. And so I did.

Some notes on the technique:

1. This book is largely comprised of a straightforward, picaresque narrative about a character named (Osgood) Barnaby Saltzer. Chapters begin and end and as a result you’ve moved on several moments/months/years in his life and been entertained along the way. However, Barnaby had a younger brother named Creynaldo–a prodigious genius, having died when he was only seven and already written many cherished works–and the book features a great deal of his poetry/drawings as well. Furthermore, at the end of many chapters–and before a few, later on–there are notes from conversations between this story’s author Barnaby Saltzer, and his editor; hence the occasional portions where large X’s are printed through entire pages that the editor deemed unworthy–a practice of ‘bracketing’ in the deconstructionist tradition that only serves to make you read harder.

2. Though obviously influenced by the Pynchon novels available at the time (1969) in his extremely funny descriptions of a dangerous and fast-paced America, I daresay Rauch achieved something entirely novel with this work. This is apparent on the cover, ‘An Obvious Fiction,’ calls to mind the typing of Exley’s A Fan’s Notes as ‘A Fictional Memoir’. Rauch seemed to know at an extremely young age that he’d achieved something unprecedented in this regard. Of course variations on this theme of the broken and commented-upon narrative existed, but not quite like this and very seldom in a package as successful as Dirty Pictures.

Ekphrasis Flash

There used to be some CW pedagogy on here. Maybe there still is, I don’t know. Been away for a few days. My microwave died recently, etc. Anyway, I just remember a lot of people didn’t like it or something, so I thought I would go ahead and add some more.

Ekphrasis sounds like a skin disorder, but is actually when one medium of art attempts to relate to another medium. Like dancing about architecture or fucking about radishes, for example, etc. This can be a fructiferous exercise for a class (or workshop or, you know, just a group of people who like to write [It’s Ok to write just because you like to write, just like it’s OK to run just because, you know, you like to run or collect cats or whatever]). This exercise is ofttimes done with poetry and that’s OK I suppose, but I’d prefer you tried this exercise with flash fiction.

I’ll define flash fiction as under 750 words, since defining the genre any other way—by style, history, worldview—is reductive and wrong.

You’d probably want to show an example. An example actually cracks open the synapses. In fact, writing directly after an example (not with a lag) is a little teacher trick I’ll pass onto you. Sort of like your knowledge is lighter fluid and imagine your students have heads made of charcoal. Pour a little knowledge on their heads. Then toss in the match. The match is writing. This analogy is pretty forced, but it makes a shard of sense.

If you want to use the word “multi-media” on your salary review document, you could show this video, an ekphrasis by Pamela Painter:

Now you can say, “I like to use multi-media in my class…”

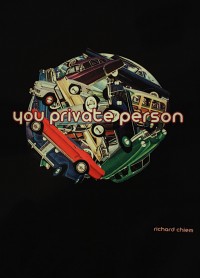

25 Points: You Private Person

You Private Person

You Private Person

by Richard Chiem

Scrambler Books, 2012

139 pages / $12.00 buy from Scrambler Books

1. I appreciated what I imagined was the time spent in deciding the titles for the individual stories. They seem to be an art form in it of itself and are often cast aside with boring, one word placeholders in other collections. But these seem like really good tweets, or prompts for possible flash fiction.

2. I was intrigued before even opening the book. Between the nice cover art by Mark Leidner and the trio of blurbs on the back cover that force you to not only start reading but, when you’re done, place the book face down so as to show off the insanely nice and potent words of Dennis Cooper, Kate Zambreno, and Blake Butler.

3. It’s a small book, under 150 pages, but the actual size of it and layout of the pages w/r/t to font, spacing, etc, make it feel much more hefty and somehow more important.

4. This is the first thing I read from Scrambler Books. I have certain small presses that I’m comfortable with purchasing pretty much anything and everything they release. If this book is any clue to Scrambler’s future intentions than I plan on adding them to my queue, to the detriment of my bank account.

5. I’ve never read Chiem before this. I went back and found some of his stories online. They didn’t disappoint. I love it when an author is able to bridge the difficult gap between lone stories in online journals and a fully formed collection in print.

6. I’m jealous. I’ll admit it. Chiem is born a year after me and he’s a hell of a writer. He’s put together a collection of stories that I aspire to replicate in my own way. This book has a maturity behind it that hides the fact that this is his first published book.

7. “The first fiction is your name,” Eileen Myles. Seems like a perfect quote to open the book. It put me in a subdued and contemplative mindset before the first story.

8. There is something in this book for everyone. As much as I hate when I read the previous statement in a review for this book, it’s true. Short fiction, some prose poetry, fragments of stories, linked narratives.

9. You’ll definitely feel a little better about the future of the short story after reading this collection. Chiem is a young writer who has a stranglehold on his craft, who has finely tuned his pen to hear the whispers of our society, the forgotten people, the discarded images are given a second home.

10. The opening paragraph of the book is perfect. It combines his greatest gifts as a writer: his pitch perfect sense of how to put together a sentence and his ability to allow himself the freedom to wander with his thoughts while still maintaining the discipline to reign it all back in and bring the reader to a larger point, usually profound yet understated. “Cigarettes can levitate you and the bare weight you have very bored in your head and you have never known you were unhappy until the feeling leaves you like imagined geese from hills eager for migration. Birds are so fun to imagine. This all comes from years of wanting to know how to fly standing out on balconies pretending sex is the name same as flight because surely geese can feel in the air like I do when her eyes go crossed when bedrooms soften after foreplay when language works much like animal speech. Only by repeating each other’s names. I do believe all birds are named Chirp.” READ MORE >

April 18th, 2013 / 4:07 pm

A Novel by Harmony Korine

“This reissue is 100% identical to the original text and also 100% more awesome!”

Drag City has just re-issued Harmony Korine’s long out-of-print novel A Crackup at the Race Riots, first published in 1997.

On Letterman, back in 1997, Korine described it as “The Great American Choose Your Own Adventure Novel.”

Without giving too much away, I’ll say it behaves like a bumblebee. Notes of David Markson, Joe Brainard, and Kathy Acker can be detected. Also Andy Warhol and Andy Kaufman. But these flavors are also misleading. Both Tupac and MC Hammer make appearances. Not to mention a startling revelation about Jackson Pollock’s sexual proclivities.

I’ll soon be interviewing him about it for The Paris Review Daily, so be on the look out. I plan to ask him about the relationship between the book and his avant garde tap dancing movement.

Buy it from Amazon $12.89

But it from Drag City $18.00 / or $9.99 for PDF

Still wondering which posts you consider the best ever published at this site. Will compile the results.

This is your chance! Also, should sex be outlawed?