Amina Cain’s SUMMER READS

Amina Cain’s summer reading recommendations:

***

Work from Memory by Dan Beachy-Quick and Matthew Goulish (Ahsahta Press, 2012)

Work from Memory by Dan Beachy-Quick and Matthew Goulish (Ahsahta Press, 2012)

My first three recommendations are books I myself plan to read this summer (and you should too!) and this one is at the top of my list. Work from Memory is in response to In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust, and Goulish is a performer whose work with Goat Island I’ve loved as much as any of my favorite books and those performances have taught me as much about writing as reading has. I’m also fond of Dan Beachy-Quick’s work because of what feels to me like a deep calmness within it. I can only imagine the territory the two of them cross into here.

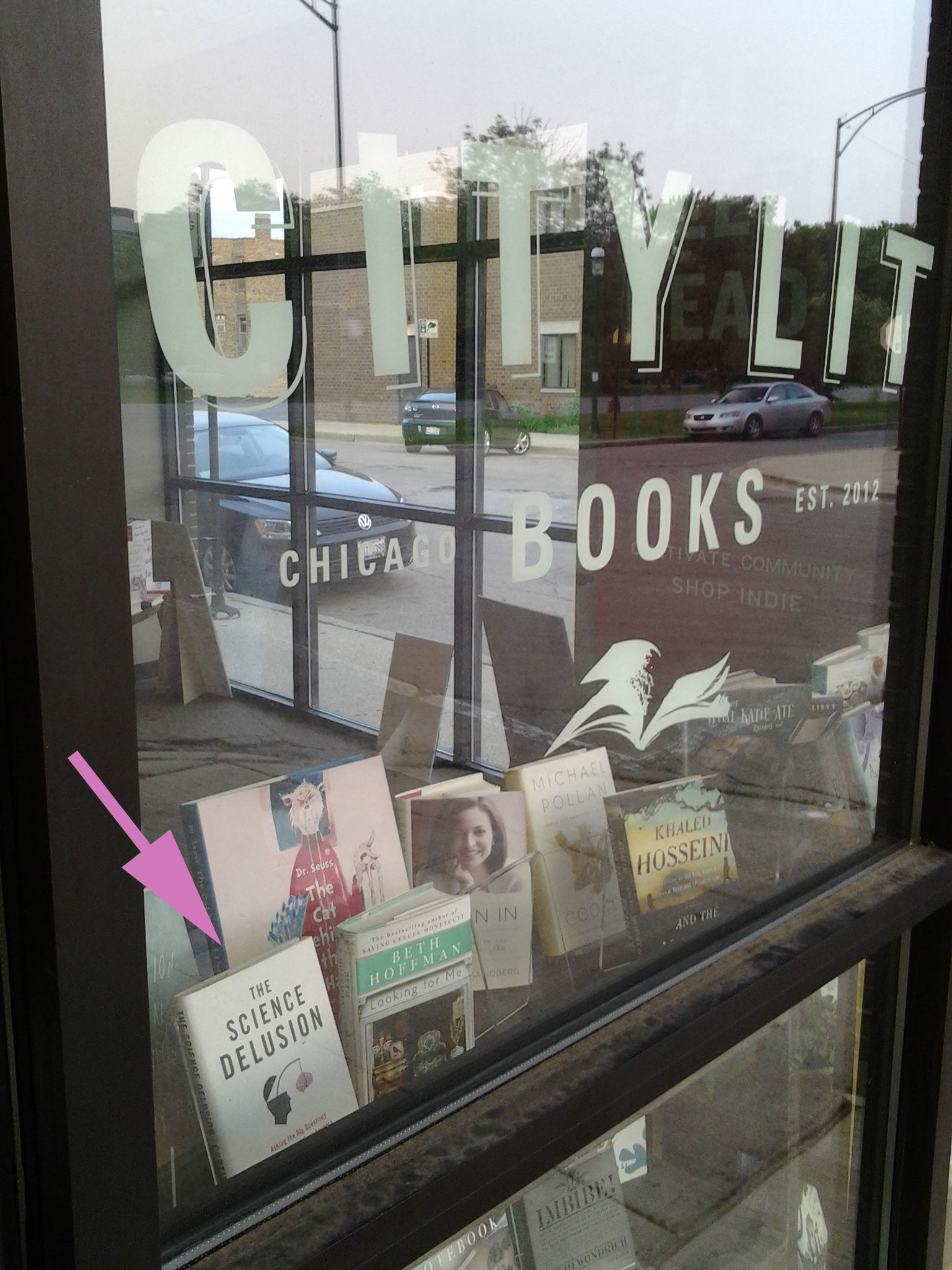

Murder by Danielle Collobert, trans. Nathanaël (Litmus, 2013)

Murder by Danielle Collobert, trans. Nathanaël (Litmus, 2013)

This is a short novel I’ve been waiting for all year, dedicated reader of Danielle Collobert (and Nathanaël) that I am. Another title by Collobert, It Then, is one of the most brutal books I’ve ever encountered, performative in its brutality and fragmented in a way that is more elegant than I thought fragments could be. Murder was written during the Algerian war and originally published by Éditions Gallimard in 1964, and from what I can tell, looks closely at the severity of human existence.

READ MORE >

June 12th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Top Three Suicidal Gods

3. Mercury

Mercury, god of commerce and poetry, discovered that for most of the contemporary world, he was just the basis for a class of comic book superhero who ran fast everywhere and defeated terrible, terrible villains by running fast at them and away from them. Mercury, who like commerce and poetry, was of an erratic personality type, slumped into a despondency and decided it would be best to not be at all. Mercury decided to run himself to death, and so he found a long, flat place, and connected one end of it to the other, and made a twist in the center. It became a möbius strip. Mercury ran and ran and ran, waiting in motion for his legs to buckle and his heart to burst. For the knitted together sections of his heart to expand and contract faster and faster until they pulled themselves away from each other and splatter blood inside his chest. READ MORE >

THE ACT OF MEMORY, “LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD” & THE THING OF INTENTION

SUBJECTIVITY OF MEMORY

Suzanne Corkin’s book Permanent Present Tense: The Man with No Memory, and What He Taught the World chronicles the fascinating case of Henry Molaison. Upon receiving a catastrophic lobotomy at the age of 27, Molaison continued his life as an individual incapable of forming new memories. For the remaining 55 years of his life, Molaison was closely studied by Corkin: his unique tragic circumstances constituted him as a one of a kind empirical specimen of anterograde amnesia, the medical term for his inability of forming new memories. Corkin found in him the ideal means to gain a deeper scientific understanding in the field of neuroscience[1].

Unlike the Drew Barrymore character in 50 First Dates, Molaison spent his amnesic reality in the company of a meticulous observer and not the romantic goofiness of Adam Sandler. The focus of Corkin’s book is the scientific exploration of how new memories are cerebrally processed. Corkin observed the short-span consciousness of Molaison’s new memories along with the variation of the feelings and thoughts he exhibited, as everyday provided a new opportunity to reassess her specimen all over, evaluate and reevaluate the pertinent data. Despite the repetitive occurrence of the same questions within his short-span of memory, Molaison’s responses were sometimes indicative of the formation of new memories. This analysis served as a catalyst for a new neuroscientific theory: contrary to previous popular belief that memories “were indelible snapshots of sense experience, stored in chronological sequence like the frames of a celluloid film,” memories are actually located in more than one location in our brains.

Mike Jay’s exceptional review of Corkin’s book[2], aptly entitled “Argument with Myself,” starts with a powerful definition of memory. Jay concedes that memory shapes one’s identity, but he argues that in addition it simultaneously functions as the (mis)apprehension of a well-founded, whole self: “memory is not a thing but an act that alters and rearranges even as it retrieves.” In this framework, it is evident that the way we conceive our individual realities, as they are constructed by all the memories we hold, are suspect. The manner in which all of us accentuate the details of what happens, both to us and in the world surrounding us is marked by subjectivity. While the degrees of each person’s paranoia and tendency for narrative exaggeration vary, there is no doubt that in most “realities” much is not real.

In an endeavor to make her students grasp this very fact, Mary Karr once began teaching a creative writing course by performing getting in a huge spat with the educational institution’s program director[3]. Once the program director exited, Karr revealed to her students the argument they had witnessed was a simulation. She then asked them to write down their observations and perception of the incident. The students had an arduous time reaching consensus on a collectively agreed objective account of what had just happened in their classroom. This exercise swiftly presents the validity of the very ambivalent nature of objective memories.

The Family Project by Julie Sokolow

– – –

Julie Sokolow is a musician, filmmaker, and writer whose work has been acclaimed by Pitchfork, The Washington Post, and Wire, among others. She’s a 2012 recipient of a Creative Development Grant from The Pittsburgh Foundation towards her first feature-length documentary, Aspie Seeks Love, about an Aspergerian writer looking for love on the internet. The teaser was recently featured by Boing Boing.

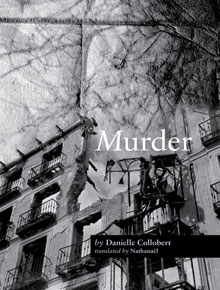

25 Points: alphabet

alphabet

alphabet

by Inger Christensen

New Directions, 2001

64 pages / $12.95 buy from Amazon

0. Inger Christensen—that petite, Danish demigod with her propensity for potted plants and the wild unknown—must have been hounded by the idea of growth. By what is massive. I guess if you look at/dwell on the vastness of things for long enough, you’ll predictably find yourself engaged with death options, the tempered dark where there are no underthings to stabilize you—and you are a little dust, alone with the chilling and the growing of yourself. It’s just you you you and the big outside.

1. Christensen’s alphabet is a sprawling network, shaped by the Fibonacci sequence that signifies nature’s inclination toward animal, exponential levels of growth and similar vanishings of decline. There’s an incantation stitching the poem, especially its beginning, that simply verifies the existence of things:

killers exist, and doves, and doves;

haze, dioxin, and days; days

exist, days and death; and poems

exist; poems, days, death

Death exists, details exist, the small monotony of days exist, all alongside one another.

1. I once read the entirety of alphabet in one of those concrete courtyards, the sad kind that’s trying to cute-up a hospital. I read it another time out loud for someone (although finishing was weird and uncomfortable because I was just beginning to tell, although I liked this person at the time, that they were not really interested in me and definitely not interested in 80-page metaphysical poems structured like the Fibonacci sequence), and another time on my bedroom floor with a whole .75 of OT that was looking nothing like a group sport because I was sad about something or something. And many times before and after that I can’t remember anymore. One magical person said, when I asked her about alphabet, that it made her think about cornfields a lot.

2. I sometimes try to relate my deep affection and appreciation for the state of Iowa, and I always think about cornfields that continue past the curvature of the earth, this massive output of production that literally exceeds our capacity to see it, much less understand it. “wheat in wheatfields exists, the head-spinning / horizontal knowledge of wheatfields, half-lives, / famine, and honey . . .”

3. Sometimes all it takes to be humbled is just the existence of certain things.

5. I’m shocked and quieted every time I read a newspaper, but not like I am by cornfields or incomprehensibly vast networks of connection. Although, the more I think about alphabet and re-live those declarations of both physical and metaphysical existences, the less I see the distinction.

8. There are some lines in there that simply state the death count for some great tragedies— “140,000 dead and / wounded in Hiroshima / some 60,000 dead and / wounded in Nagasaki”— and these numbers stand still on the page. The lines are always wavering between the porous and the immovable, the intimate and the intergalactic.

13. I wonder what it would look like, speaking of networks of connection, if Christensen had written a long poem/book of poems about the internet. Like, would that be beautiful? Would that be sheer terror?

21. It’s impossible not to talk about Susanna Nied’s translation. In an interview at Circumference last year, Neid said that she started working on alphabet’s translation in secret: “I didn’t tell Inger I was doing it. For the time being, I didn’t want anyone else’s input, not even hers. I had a very strong sense of what the poems could become in English. I kept shaping and reworking. Interlinked sprials. Double helix. Beauty and destruction. I was possessed.”

34. You can easily be possessed by Christensen. If you hear alphabet being read aloud, the words bend towards rapture, like hypnotism. Partly due to the steadily revolving repetitions—existence, vanishing, existence, vanishing. READ MORE >

June 11th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

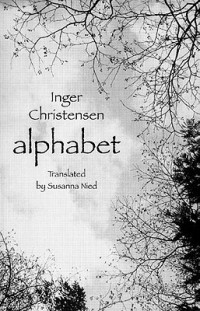

Curtis White will be reading in Chicago this Thursday

At City Lit in Logan Square, at 6:30pm. Curt will be reading from his new book, The Science Delusion: Asking the Big Questions in a Culture of Easy Answers, which just came out through Melville House.

I did my Master’s degree with Curt at Illinois State University, and he’s one of the smartest and best writers I know. (He’s one of the two profs who first got me reading Viktor Shklovsky.) In the 1980s, he and Ron Sukenick transformed Fiction Collective into FC2, and I learned about FC2 (and ISU) partly through the two “sampler collections” they put out (something I wish more presses did). Curt’s also written seven works of fiction, including The Idea of Home and Memories of My Father Watching TV, and now five works of nonfiction, including his infamous attack on Terry Gross (among other things), The Middle Mind. (He may not have made Gross cry, but he sure pissed off a lot of her fans.)

I’m only halfway through this new book (and will be writing more about it later), but so far I’d describe it as an attack on the idea, currently very en vogue, that scientific knowledge is the only or most superior form of knowledge, and thus the only means of accounting for what it means to be human. Right from the start Curt shows how much of science’s own knowledge is shoddy and unexamined. For example, it’s not uncommon to hear scientists like Stephen Hawking claim that the universe is beautiful, but how do they understand beauty? Not very well, Curt argues. Like in The Spirit of Disobedience, Curt demonstrates how other intellectual traditions—specifically Romanticism, which he traces through the Beats and punk—offer a way around and past some of the more inane debates consuming so many today, such as “science vs. religion.” Plus he’s funny, too.

If you’re in Chicago this Thursday, come by and hear Curt! Discussion will follow during which you can ask him embarrassing questions.

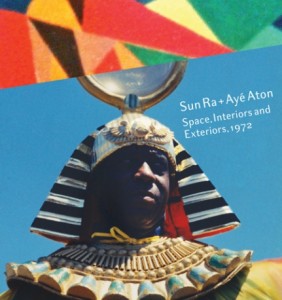

Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972

Sun Ra + Ayé Aton: Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972

Sun Ra + Ayé Aton: Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972

By John Corbett

PictureBox Inc, April 2013

112 Pages, $27.50 | Buy from PictureBox

Opening with several candid shots of Sun Ra donning full afro-futurist regalia in Oakland, filming the quintessential Space is the Place, Space, Interiors and Exteriors, 1972 finds Sun Ra himself in the foreground. An interesting choice, really, due to the fact that a large majority of the book focuses on Ayé Aton’s murals, painted primarily on the walls of Chicago’s south-side in the early 70s. But this choice makes sense, as the brief essay included in the book lets us know, as it was the overpowering figure of Sun Ra that brought a focus to Aton’s work.

Aton, who became a correspondent of Sun Ra in the early 60s (shortly after Ra moved to New York City), eventually joined the Arkestra, touring and recording with Ra during the Ra’s most significant span of recording, the years 1972-1974, when his most well-known album records was recorded, Space is the Place. Aton & Ra’s correspondence, in the beginning, was a mentorship. Aton’s curiosity towards many afrocentric esotericisms finding, if not answers, at least a response in Sun Ra (to see the breadth of the information that Ra poured into his philosophy, take note of this syllabus from a class Ra taught at UC Berkeley in the early 70s [as an aside: the environment of Berkeley where Sun Ra could teach a class like this is so far distanced from the current reality of UC Berkeley that it’s astounding], as recounted “by Arkestra drummer, Samurai Celestial, and others.”

Two brief essays in the book present this biographical (this mythical) information before treating the reader to a gallery of Aton’s murals, photographed, often obliquely, on Polaroid film in Instant film has never been the most archival film available; in these Polaroids it’s clear that colors have faded, that the precision of the film’s chemical reactions, etc, is far from precise. The material degradation adds a level of entropy to the aura the images create. While the introduction asks us to imagine rooms where entire walls are painted with fluorescent paint, the Polaroids reveal rough gestures in muted colors. With time everything fades.

But the suggestion, the consideration, is a fascinating one. As another essay points out, none of the photographs of Aton’s murals depict people in front of them, they are isolated in space, often even destabilized away from their position on walls, embedded in the flatness of the picture plane. In the late 1950s Sun Ra started calling his music “space music” because ” the music allowed him to translate his experience of the void of space into a language people could enjoy and understand” (Wikipedia). With these photos, the viewer is floating in a void of colors long faded. The dream is dead, and I wouldn’t be surprised to find most of these murals either painted over or felled with buildings during destruction.

My favorite mural, documented by a square Polaroid stamped with the month of “January” but bearing no year, finds a ram’s head above four staggering lines of grey, set within a large silver/white star-burst, across a field of pinks and oranges with black accents carrying through the field. The nothingness of the image plane is violated by a minor intrusion: that of a golden chandelier, hanging from a white ceiling. The reality of the murals becomes uncanny. This is a step towards a necessary mysticism, used by Ra and others to strive towards freedom, borrowing Egyptian symbols and steeping them in Biblical revisionism, a reality that allows the oppressed a sense of revolution. Space is the place, space is the place. The field turns into colors and every man and woman is wearing a costume that disorients. It’s after the end of the world–don’t you know that yet?

In 1968, Kenneth Anger visited the great pyramids of Egypt with a cavalcade of junkies, musicians, artists, and magicians. Costumes were brought. Anger’s greatest film, Lucifer Rising was filmed. Problems followed. The film eventually was released and has been recognized for its brilliance. Sun Ra, on the other hand, refuses to just make his film. The costumes were part of life. Life was revolutionary and within this revolt there was a refined aesthetic insistence. Aton’s murals carry this aesthetic insistence further, into the banalized reality of those who don’t have the freedom to live in Sun Ra’s world permanently. The murals serve as a reminded.

June 11th, 2013 / 11:27 am

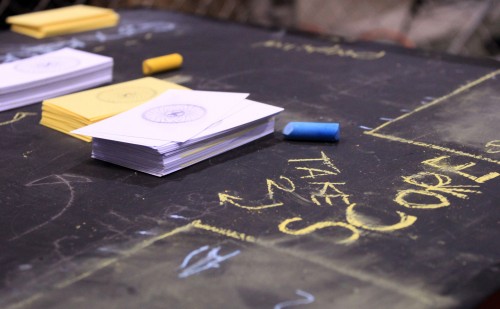

Making Games: Stumbling from Design to Debut

We had one semester to make a game.

The class was through the California Institute of the Arts’ Integrated Media department, which styles itself a meeting ground for complimentary métiers. It met each Monday morning in the school’s chilly bowels for a scant two hours – just enough time to write something on a chalk board, high-five or disagree, and then not see each other for a week. It’s a wonder we made anything at all, let alone debuted a prototype at a crowded convention called the Maker Faire three hundred miles north. What we brought is not what we intended – a partially miscarried hybrid of real and vestigial features – but game development, like any collaborative undertaking, isn’t a straight shot.

Our group was nigh-ideal: five graduate students and one talented BFA, no one from the same background. There was a programmer, a theater set designer, two breeds of visual artist, an ambient musician, and myself – the writer. Previous groups had gone the techy route, rigging RC cars with baby monitors, but we wanted to straddle multiple media – to build a game that played in physical spaces, drew from digital content, and answered to verbal interaction. By the end of our first class we had a draft.

“I’ve never seen a game come together so quickly!” the class’ instructor announced. “It’ll be great at the Maker Faire.”

That’s the thing, though – you can chart a voyage to the moon, but landing on the surface is another thing entirely. High-concept ambitions are irrelevant until you see them through.

Our design on paper was a monster, something you would murder if you found it in a lab. The hulking Franken-game included real-world installations, app-based digital avatars, RPG-esque progression, and heavy narrative content.

Sounds rad, right? Proposals often do.

Johannes Göransson’s SUMMER READS

Johannes Göransson shares what’s he’s reading this summer:

***

This summer I’m reading:

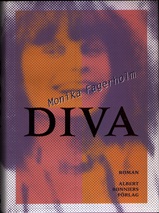

Monika Fagerholm’s novel Diva: It’s a novel about this girl Diva who does some crazy stuff, but it’s also about a whole cast of characters, such as TruthMary and her sister Kari. Kari loses the ability to speak so she tries to re-learn it by listening to recordings of herself saying basic sentences, which Diva hears through the wall (they’re neighbors). And her hair grows really long so she lets it out and the neighborhood boys climb up on it. Years later Kari lights herself on fire in a telephone booth. The book is written in this incredibly cyclical style, where the same story gets told over and over, slowly revealing more and more details. I don’t think this book has been translated, but some of her more comprehensible books have been translated: American Girl and Glitter Scene. I’m going to read those too.

Monika Fagerholm’s novel Diva: It’s a novel about this girl Diva who does some crazy stuff, but it’s also about a whole cast of characters, such as TruthMary and her sister Kari. Kari loses the ability to speak so she tries to re-learn it by listening to recordings of herself saying basic sentences, which Diva hears through the wall (they’re neighbors). And her hair grows really long so she lets it out and the neighborhood boys climb up on it. Years later Kari lights herself on fire in a telephone booth. The book is written in this incredibly cyclical style, where the same story gets told over and over, slowly revealing more and more details. I don’t think this book has been translated, but some of her more comprehensible books have been translated: American Girl and Glitter Scene. I’m going to read those too.

Diva is one of the key texts in Maria Margareta Osterholm’s critical book, Ett Flicklaboratorium i Valda Bitar (A Girl Laboratory in Selected Pieces), which explores the figure and aesthetics of the girl as it pertained to Swedish literature. Osterholm also introduced the term “Gurlesque” to Swedish culture, and this term has generated a lot of discussion in the newspapers and has helped draw attention to some of the best young Swedish writers, such as Aylin Bloch Boynukisa and Sara Tuss Efrik. So I’m going to read this book.

June 11th, 2013 / 11:00 am

What Famous People’s P$ss$$s Look Like

[ Just as Shakespeare jauntily lifted and displayed pieces from his great store load of words pertaining to and characterizing people’s privates (including “nothing,” a favorite among feminists!) I have decided to whip out here some closely guarded tidbits about famous people’s pussies. So, come on, slap your thighs, crunch peanuts in the pit, and gaze up, all forlorn, at the sultry clouds.

And, above all, enjoy. ]

A non-pregnant Kim Kardashian’s is a furry teacup pig on its day at the spa. Showing off its nails and gleaming skin. The clit’s a snout and it makes gorgeous and empty little squeals that no man can resist.

Paris Hilton’s is very much like a starved Flamingo curled up into a sad ball on the fringes of the high-acid waters of some South American crater lake. The sky’s filled with hotels and jails and at night the stars crowd in like ghoulish paparazzi. . . And the starved flamingo shivers like a scared Chihuahua that pees on Paris’s marble floors whenever it’s afraid or excited.

(Cormac McCarthy’s trying to work this dish into a new disaster novel). READ MORE >