Another way to generate text #8: Writing through a foreign language dictionary

I’ve spent this summer studying French, and while flipping through my copy of Cassell’s French Dictionary, I realized it contains un roman caché, just waiting to be libéré.

I’ve spent this summer studying French, and while flipping through my copy of Cassell’s French Dictionary, I realized it contains un roman caché, just waiting to be libéré.

Here’s all one needs to do:

- Flip to any random page on the foreign language side of any foreign language dictionary*. For instance, I just opened my Cassell’s to page 593 (in the French half).

- Copy down all of the English on that page, ignoring the French. (Republicans should totally love this technique!)

*You don’t need to use any particular language or dictionary. And the more dissimilar the other language is from English, the more varied the English-language results will be—see below for more on that. And of course you can use this technique using any dual-language dictionary, not just English–X, but I’m assuming English as our baseline since HG is (mostly) an English-language site.

Here’s all of the English on Cassell’s page 593:

Art & “Sound” Violence (Jhnns Göransson – A.D. Jmsn)

Ovr at the Potry Fondation (yes, the Poetry Foundation) gust blggr Johannes Göransson begins his first post with a late 19th century qute abut Kren Music by Henry Savage-Landor:

This music is to the average European ear more than diabolical, this being to a large extent due to the differences in the tones, semi-tones, and intervals of the scale, but personally, having got accustomed to their tunes, I rather like its weirdness and originality. When once it is understood it can be appreciated; but I must admit that the first time one hears a Corean concert, an inclination arises to murder the musicians and destroy their instruments.

Jhnnes gos on to tlk about ART as a “zone which both hrts and is hrt” and how, qoting his wife Jylle McSney, “snd is a knd of violence” and, fnally, sying “I am invested in this violent aspect of art: it fascinates and hrrfies me.”

So, nyways, a few hrs fter I read Görssn’s engagng Ptry Fdation pst I found myself thking again abut snd, vlence, snd-vlence, and other thngs as I lay in a rlly hot bth reaing A.D. Jmson’s xcllent “Amazing Adult Fantasy”:

You’ll be the guy who finally knifed up Indian Jones. Some’ll love you and some’ll hate you. Some’ll never believe it and never give in. Some’ll send flowers. Some’ll look for and find the younger Indian Jones.

The casl skm-reader READ MORE >

CGS’s “Drone Poetics,” or, my desire to be unobtrusive

Up at the Boston Review blog, Carmen Gimenez Smith gives real talk about being a poet-academic and the inherent privilege of it:

I often struggle with how I might best use the privilege I possess as a middle-class poet. I’m afforded the platforms of professor and writer, platforms I don’t really utilize to effect change in the world. This might be due to a cultural indoctrination suggesting that poetry is a marginal practice, yet poets such as Adrienne Rich, Denise Levertov, Gary Snyder, Brenda Hillman, and, more recently, Mark Nowak, Shane McCrae, Jena Osman, and Craig Santos Perez have utilized their privilege and platform to uncover, expose, and counter accepted narratives about living in a declining empire in which our agency as citizens is shrinking. While the government watches us, more and more poets and writers are watching back, documenting the injustices that stain our present moment. We need more of that. I should be doing that.

I’m currently editing this massive anthology with Joshua Marie Wilkinson called The Force of What’s Possible: Writers on the Avant-Garde and Accessibility (heading to an Internet purchasing place near you in 2015 from Nightboat Books). In it, we have roughly 100 original essays discussing the role of accessibility in writing as well as Badiou’s questioning of Empire and recognition. Putting together these essays, especially in light of Carmen’s BR post, I keep returning to a word: responsibility. What responsibility do we have as writers? Do we have a responsibility? To whom? Should we even care about accountability? And accountable to whom? We have this great power: the ability to tell stories. What do we do with it? Do we just recycle the same and call it new?

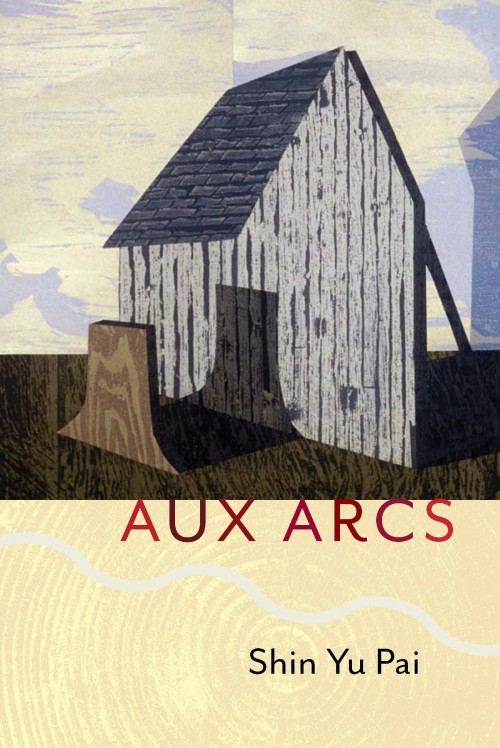

Seattle Author Spotlight (6) — Shin Yu Pai

This is the 6th Seattle Author Spotlight (previous ones were Richard Chiem, Maged Zaher, Deborah Woodard and Matthew Simmons) and I plan on running quite a few more because AWP’s coming and Seattle has plenty of talented and interesting writers.

Shin Yu Pai:

Shin Yu Pai is an ambitious, bright and engaging poet, photographer and C.O.O. of the National Asian Pacific Center on Aging: “the nation’s leading advocacy and service organization committed to the dignity, well-being, and quality of life of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) as they age.” Shin Yu’s most recent book, Aux Arcs, has just released from La Alameda Press and is rooted, for the most part, in her experience, and situation, of being in a small town near Little Rock, Arkansas.

I thoroughly enjoying chatting with Shin Yu at Elliott Bay books (this is where I’ve met and spoken, thus far, to all featured Seattle Authors). We spoke some about the form and content of Aux Arcs and this branched us off into other chatting about assimilation, the way different people treat each other, etc. There were other things I’d planned on talking about but the time kind of flew by. And that’s always a good sign. Shin Yu has a kind of spark, presence and good sharp energy that just makes you want to be around her.

Brief Bio:

Shin Yu Pai is the author of several poetry collections including Adamantine (White Pine, 2010), Sightings (1913 Press, 2007) and Equivalence (La Alameda, 2003). She has been a writer-in-residence for the Seattle Art Museum and has received grants for her work from 4Culture and the City of Seattle. For more information, visit her website

Brief Interview:

Rauan: you’ve lived as an adult (and a writer) in Seattle, Texas and Arkansas (among other places)– can you tell us a bit about the differences in living in these places and how these cities impacted yr thinking (and therefore yr writing)? READ MORE >

August 2nd, 2013 / 12:30 pm

THE SEMANTICS OF CHRONOTOPES

BILLY: THE SPORT

“Billy” fucked the love of my life. [1] I had known Billy for a longer time than I had known the love of my life, and that still holds true from an objective standpoint where time is universal. I knew him to be the person I was not expecting to be friends with today, not because he fucked her–because I was actually not expecting that at all–but because our friendship was extremely mild. [2] There were also haphazard and unrelated–as they pertain to each of us as friends–shared chronotopical coordinates. We happened to be at some of the same places at a lot of the same times: the concert where I met the girl I dated before I met the love of my life, the liberal arts institution in the Midwest we both attended and, finally, New York.

Understanding how memory is determined by the chronotope has always been an arduous battle between logic and emotion, because time becomes connected to the space the memory is produced in and the intensity of the experience held in each memory shapes one’s perception of time. Time may appear to no longer be measured by any watch or clock, but by the strength of one’s emotions. Space is also prone to personal subjectivity, as past memories tend to engender feelings of the past, arguments fought and wet kisses shared.

To construct an understandable narrative, the creator must give in to the limitation of linearity, regardless of how convoluted the structure of the linearity becomes. [3] As a producer of memories who also chronicles them in prose, I have often manipulated myself for days until I surrender to an objective need to stop giving in to my desire for the (re)production of an intense memory.

Last time I saw Billy we met at the Highline, [4] which is always awful and never ceases to surprise with how awful it will be over and over again. Time definitely stops forever at the Highline and the space becomes a mini-simulacrum of all that is hell: enthusiastic teenagers, people who like to document their everything for antisocial media and runners who run for fun. No wonder Billy had a freakout and cried, even if the space actually had nothing to do with it. [5]

This time I was meeting Billy at a Vietnamese place in Chinatown called PHO-BANG. I go there a lot, because the wait-staff is extremely rude, but also because I like their pho and it is definitely enough for two meals, or even sometimes all the meals of a day if you get the large size with the beef chunks. My favorite detail about the kitschy exotic ambiance is the clock that is next to the counter, a clock that ticks but has stopped forever. On the clock there is a visual of the Twin Towers, a space that real time has made a non-space. I find that definitely inappropriate, but maybe I am silly to think that, especially after really loving the Tom Junod article in Esquire that beautifully conveyed the tragedy of imagery recounting the 9/11 tragedy. [6]

Goodnight Nobody

Goodnight Nobody

Goodnight Nobody

by Ethel Rohan

Queen’s Ferry Press, September 2013

138 pages

Phantom pains are a phenomena in which the patient suffers pain in a limb that is no longer part of the body. In Ethel Rohan’s Goodnight Nobody, symbolic phantom pains abound and absence makes the longing for completion more keen. There is a subdued humanity in each of the thirty stories that mix melancholy and joy with a sense of loneliness. In “The Splitting Image,” twin boys are identical apart from a missing arm on one. Despite their mirrored images, their personalities could not be more different. This disparity becomes a schism symbolized by the absent arm. One brother wants a whole arm to be complete while the other wishes his brother would “take it. Just fucking take it.” Unfortunately, it’s neither his to give nor his brother’s to take, and both are stuck as they are.

Likewise, thirteen-year-old Esther has lost her grandfather to spontaneous combustion in “Out of the Ashes.” Speculations from those around them run rampant, including ones that his death had something to do with supernatural forces. All the talk has her disconcerted and her mother has taken it hardest, verbally exploding at someone who asks about the cryptic nature of his death. Esther is helpless to act and wonders if her grandpa truly had made some type of sinister deal. The threat of such a possibility scares her and her sense of alienation is emphasized by the burn of the sun.

There’s an organic melding of themes and the obsessions the characters wield in many of the stories. In “Bee Killer,” the disconnect between a husband and wife is represented by a hive of bees the husband maintains. The emotional gulf between them is both grand and dwindling, difficult to articulate and yet swarming with stinging malcontent. He seems more concerned with the bees than her well being. It’s the quiet discontents that add up and eventually overwhelm:

“What about the queen?” I said. “The colony would be nothing without the queen.”

“She’s as much a slave to duty as the rest,” he said. “Average queen lays two million eggs in her lifetime.” He went on to tell me how a sick bee leaves the colony to die alone, so as not to infect the others. “Sacrifices himself,” he said.

“Plenty of us do that,” I said.

A photographer from “Darkroom” is going blind from a condition that is both “genetic and degenerative.” Fueled by her pending blindness, she wants to capture “the photograph of a lifetime.” The permanence of the camera becomes a substitute for the deterioration in her eyes and the visibility that will soon escape her. Capturing an image of the giraffe becomes the specific target and she goes on an adventure with her husband to get it. It seems foolhardy, until we realize it’s her way of warding off the inevitability of permanent darkness:

“I wish the blindness would just come and take my eyes right now.” Her voice shook and she held herself. “I hate the waiting.”

He pulled her into his arms and hid his tears in her hair, seeing those zoo elephants from so long ago and remembering the tickle of the animal’s trunk on his palm and the side of his face, its breath warm and pleasant, but searching, searching.

All of Rohan’s characters search for things they can’t have and the prose is elegantly wrought, neither excessively sentimental nor overtly flashy. Instead, there is a lush rhythm in the sentences that renders observations in natural beats. Judgment is suppressed in favor of an understanding of the complexities of friendship and family, however quaint or unusual. Irish settings for many of the stories act as a unique brogue against the landscape of the collection. Everyone is drifting, flotsam from the shipwreck of modern conjunctions. The shorter length of many of the stories make them seem like splices from a bigger sampling, a gauge on the tempo of a bigger macrocosm.

August 2nd, 2013 / 11:00 am

Price of Experience by Clayton Eshleman

Price of Experience

Price of Experience

by Clayton Eshleman

Black Widow Press, 2012

483 pages / $24 Buy from Amazon or Black Widow Press

The Price of Experience is a broad sampling of Eshleman’s prodigious output in a variety of literary forms: poems, letters, interviews, book reviews, essays on contemporary art, and lectures on ice age cave art, are all brought into the mix alongside various memoir bits and notes on his numerous translation as well as editorial projects. (Eshleman indispensably translates the poetry of both César Vallejo and Aimé Césaire, among others. He also edited the seminal journals Caterpillar and Sulfur.) This would be considered an “Eshleman Reader” if only somewhat incredibly it didn’t follow on the heels of Black Widow Press’ previously published The Grindstone of Rapport: A Clayton Eshleman Reader (forty years of poetry, prose, and translations). Meanwhile, it also looks forward to their publication of Penetralia (a fifty-seven-year poetry retrospective) in 2015. It’s daunting (and perversely thrilling) to imagine what the page count for the upcoming “retrospective” might turn out to be as the other two books come in at around 500 pages each.

Eshleman grabs his book’s title from lines of William Blake’s The Four Zoas and the lesson expounded by the work of the poet-mystic-printer is ever apt. Eshleman quotes an extensive passage, but here are the opening lines:

Or wisdom for a dance in the street? No it is bought with the price

Of all that a man hath his house his wife his children

Wisdom is sold in the desolate market where none come to buy

And in the witherd field where the farmer plows for bread in vain

In essence, given this epigraph, which ends “It is an easy thing to rejoice in the tents of prosperity / Thus could I sing & thus rejoice, but it is not so with me!” Eshleman seeks to frame this retrospective accounting of his work in a fashion which demonstrates how thoroughly his writing arises quite literally from struggles surrounding the circumstances in which he’s lived. There should be no doubting that Eshleman has done his fair share of downward scraping into the barrel of experience, bottomless as it may be. He has always returned to his work positioning his imagination via writing in the hands of forces over which he often feels no control. The resulting discoveries astound him as much as anybody else. In fact, they sometimes astound him quite a bit more than they likely do anybody else.

The limits of Eshleman’s writing arise when his impulse for self-expression overrides and self-indulgence swells within him, his proclivity for excess then gets the better of him. One case in point: while detailing his relationship with poet Paul Blackburn, Eshleman describes how his own personal demands tore him away from composing a poem for Blackburn’s second wedding and instead turned him towards writing a massive poem—as yet unpublished in its entirety—full of his working through deeply personal psychological material from out his own past.

August 2nd, 2013 / 11:00 am