Do you explain your poems when you give a reading? Maureen Thorson raises the question.

FUCK YER BRAND, IMMA DO ME (/help me figure out my brand?)

[u shd probably read the NOTE(S) as they come up for cohesion, but do as u wish, obvi]

so there s a lot of things that have been going on here, on our dearly beloved htmlg. there seems to be an even bigger emphasis than ever before on attn. and i won t lie, it is nice to feel that w/e it is i might have written here might have been read or provoked a thought to someone—ANYONE—outside of me. but the reason i am writing this, right now is to set up a personal statement of sorts for how i want to use this site, as someone who regularly (?) tries to put stuff up…

MISSION STATEMENT(S)

I will refuse to care about being “cool.” I reject the notion of a grotesquely narcissistic coolness in an alt lit universe, where we are all nerds, when viewed through the larger lens of people who are not only unaware of this lit stuff, but also actively ignore its existence.

Perhaps I am just the biggest loser in the universe, but I like to care. If I did not, maybe I would not want to write. The reason I started writing was to figure out things I was genuinely curious about, not always in a healthy fashion. It was not to one-up anyone, not to be smarter in a gimmicky sort of way that will fade and might feel cheap in a couple of years.

HTMLG was one of the places online I constantly returned to when I was in a cubicle day after day doing shit I hated, trying to find a way out. To me, it used to be a liberating space, a meaningful forum that introduced me to writing I care for, and still value. Now, it is confusing. I have the hardest time figuring out the intentions behind what is being written. Sometimes I wonder if pressing “publish” was the entire goal of some contributor; I do not think it should be. [1]

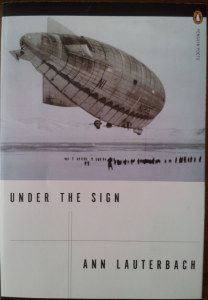

An amazing book of poetry was loaned to me, to remind me of my incentives and goals. Ann Lauterbach is brilliant, even though she cares. Or maybe because of it. I do not write poems, but her intentions—as presented in the middle section of “Under The Sign” are ones I would like to have as ideals.

So perhaps caring is not so bad. I will not actively try to not care about writing; writing by those who don’t care does not interest me.

But to care, one needs to put something at risk. One must “open,” perhaps even lose a part of their “security”—usually stemming from exercising a controlled performance of confidence—by showing insecurity. Being clevererererer just shouldn’t cut it if one wants to be true to oneself. [2]

I like the way Lauterbach understands writing. I wish we all agreed on that a little more, but I won’t force it upon you, because that would go against my principles.

NOTE(S)

[1] It is entirely possible that the reason I feel this way about putting words together in a creative way is because I did not study it. Maybe the excessive studying of something leads some of my fellow HTMLG contributors to an insipid cynicism that is often reduced to “being smarter.” Maybe it has to do with the frustrations of a young writer—or new, actually— as an immaterial existence in a material universe: the rewards of writing are rarely fiscal.

The fixation on rapid success that is intrinsic in late-capitalism has infected our immaterial universe, stigmatizing creative intentions. And I am aware money is—and probably will be—an issue for a lot of us/ you/ whatever you want me to say. But to let it dictate creative intentions would be embracing defeat.

Meet Charles Ozburn: His Work, Thoughts on Childe Harold, Etc

***

After I read at Mellow Pages in the Fall I was greeted by a man with a deep voice. I was in a bit of a fog-tunnel, as I usually am after readings, and it took me a while to figure out that this man (Charlie – Charles Ozburn) was speaking about Tiresias: variously male and female, etc. One of the great things, of course, about reading in different places is that you meet new and sometimes great people. Charlie is an example of the latter. And, soon, I found out that Charlie has a real and sustained “thing” for the club-footed Lord Byron’s work. And, in particular, Childe Harold. So, into the late hours that night I Brooklyn hung out with Charlie and other Mellow Pages folk. And then kept in touch with Charlie.

***

And, so, anyways, to follow is Charlie’s take on why Byron and Childe Harold are still highly relevant as well as a couple of samples of Charlie’s novel, A Well-Spun Spoon (of a Lark, a Lily & a Loon), where he attempts to “reflect the contradicting faces of Childe Harold against one another to, in Venus Effect, split the Byronic Hero into two (a he and, of course, a she)”

***

RK: I’ve seen the words “Childe Harold” in print a few times, I guess, but I don’t believe I’d ever heard them in conversation before I met you. And I know Byron’s work, especially “Childe Harold,” is important to you. But can you tell us please why it’s worth reading?? (what could a reader get out of it that he/she can’t get anywhere else)

CO: There exist some very basic assumptions of the human condition called human emotion, which–as expressed within an artistic medium, a plot line or even day-to-day interaction–may seem simplistic today. However, without Childe, such assumptions do not exist. For from Byron’s ink was born the founding strokes of the Modern Man, but nonetheless it is ink so far ingrained within our beings that it is often taken for granted today if noticed at all. Childe’s mark, like the faded mirror you see, is as ubiquitous as is felt; as important as is faded as is masked as is shrouded dark; more heard in the echoes of our subconscious than is shouted aloud; certainly more misunderstood as a literary key word taught to the too young an age to be realized any substantive credit due. For everyone knows of Lord Byron and, of course, every Dick or Jane, who ever paid a bit of attention in high school English has heard, if only in passing, the term ‘Byronic hero’ – but, given you are not the first person–much less poet–who has with earnestness admitted to an honest ignorance of Byron’s legacy, I suppose it is safe to say today that the roots, flowers, fruits and weeds born of Byron and his work have grown so tall, so far, so wide, so plump, so beautifully wretched, so wretchedly right, so obviously plain that the shadowing stature of their booming bloom have all but sheathed the very soil and seed from which beneath same sprouted.

Childe Harold is the lightly veiled pen-to-page fictive form of young Lord Byron written contemporaneously in reflection along his own path from disillusioned playboy gamboling in retreat of war about the exotic pleasures fields of faraway fanciful worlds to finding therein the world out there lay so much more than perceiving one’s own superiority and self-serving one’s self righteousness of pity in vain; because so many of us today with our world and war weary eyes and smug cachets find ourselves in his same embarkation shoes, entrapped in a claustrophobic cynicism our own and gamboling about lost in this newly found unfamiliar land where all are free to know all; because not only did Lord Byron embody all things Rock Star, but because he so clearly invented the role; because he was Andy Warhol 100 years before Campbell canned its first soup; because he was Lou Reed and Patti, Janice and Jerry, and Richard. Levon and Rick 200 years before Chelsea changed the game or Monterrey poised itself to pop! because he was the most famous READ MORE >

Summary of the National Book Critics Awards Finalists for Publishing Year 2013

In case you missed it, the NBCC announced their newest awards finalists. According to their selections, the only publishers publishing award-worthy material are FSG and Knopf, plus a meager handful of others that are not FSG or Knopf. Obviously the NBCC committee has never seen this list. The number of presses that aren’t FSG or Knopf would blow their minds!

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

(Knopf)

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

(Viking)

(Bloomsbury)

(Simon & Schuster)

BIOGRAPHY

(Doubleday)

(Yale University Press)

(Knopf)

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

(Cornell University Press)

CRITICISM

(McSweeney’s)

(Liveright)

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

(Verso)

FICTION

(Knopf)

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

(Knopf)

(Viking)

(Little, Brown)

NONFICTION

(Norton)

(Crown)

(Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

(Knopf)

POETRY

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

(Knopf)

(University of Pittsburgh Press)

(Copper Canyon)

(University of Arizona Press)

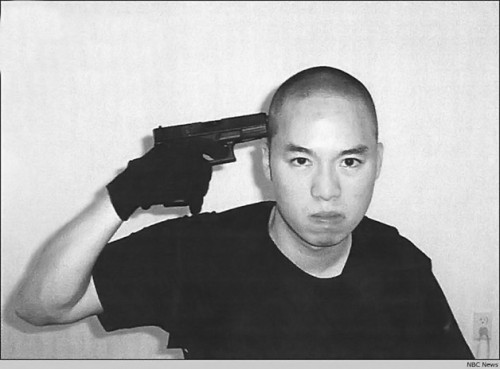

Boys Who Kill: Cho Seung-Hui

The next installment of Boys Who Kill stars Cho Seung-Hui, or Seung-Hui Cho, or Question Mark. On 16 April 2007, 4 days before the 7th anniversary of Columbine, Cho killed 32 people at Virginia Tech. First he visited West Ambler Johnston Hall, a dorm room for both boys and girls, where he killed one boy and one girl. Then he traveled to Norris Hall, a classroom building, and killed 30 more people.

Ever since Cho was taken out of his mommy’s tummy he hasn’t taken to talking. “Talk, she just him to walk,” says Cho’s great aunt about his mommy. “When I told his mother that he was a good boy, quiet but well behaved, she said she would rather have him respond to her when talked to than be good and meek.” At Virginia Tech, one of Cho’s roommates remarked, “I would see him walking to class and I would say ‘hey’ to him and he wouldn’t even look at me.” Other students concluded that he was a deaf-mute. He ate myself all by himself, and when someone offered him 10 dollars to say something, he said nothing. According to medical professionals, Cho suffered from “selective mutism.”

I, too, would prefer to be mute, and so, it seems, do other boys. Holden Caulfield dreams about being a deaf mute, and, it’s been reported by various biographers that instead of engaging in dinner table conversation, Arthur Rimbaud would just growl. Talking is terribly human — this race of creatures does in it grotesque quantities: they talk at Whole Foods, at overpriced bars, at trendy coffee shops, and, obviously, through Gmail, Gchat, texts, Facebook, Twitter, Disqus, and so on.

Cho’s contempt for normal communication distinguishes him from humans. Virginia Tech students and teachers constantly construct Cho as boy who confound expected human behavior. A professor labeled him “disturbing” and “unusual.” A student in his playwriting class said Cho “was just off, in a very creepy way.” According to Nikki Giovanni, students started skipping her poetry class due to Cho’s behavior . When Nikki told him to either cease composing sinister poems or drop her class, Cho replied, “You can’t make me.” Eventually the then head of the English Department, Lucinda Roy, tutored him privately. But even Lucinda was afraid of him. During the one-on-one tutoring appointments, Lucinda and her assistant agreed upon a code word that would prompt the assistant to summon security when uttered.

Based on this testimony, Cho is similar to a virus or a disease. No one wants to be around him; everyone is horrified of his presence. Not one to stay up into the wee hours of the morning to drink, party, and partake in sexual intercourse, Cho went to bed early and awoke early. He also played basketball alone. According to the New York Times, Cho was in a “suffocating cocoon.” (Being in a “suffocating cocoon” seems very dramatic and cosy; it also seems as if a “suffocating cocoon” would provide protection from mankind.) Virginia Tech journalism professor Roland Lazenby sums up Cho as a “shadow figure, locked in a world of willful silence.” Both Lazenby and the Times portray an incomprehensible boy who, isn’t free and liberated like Western subjects, but is held captive by a dark dangerous force. As Theresa Walsh, a girl who witnessed the killings in Norris Hall, says, “I’ve never really thought of him as a person. To me, he doesn’t have a name. He’s always been just the ‘the shooter’ or ‘the killer.'”

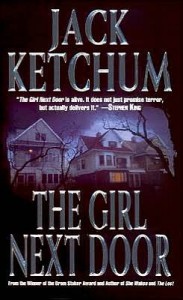

Jack Ketchum’s The Girl Next Door

The Girl Next Door

The Girl Next Door

by Jack Ketchum

Leisure Books, 2005

370 pages / Buy from Amazon

One principle guiding this year’s reading has been to delve more deeply into what’s filed under Horror. When people ask me what kind of stuff I write, I always struggle with that word, never quite sure what it’ll mean to them when I do or don’t use it. I like the word, and generally think of what I do as drawing from that side of things, but I’ve never 100% known, reading-wise, what it encompasses.

So this year I read some of the classics and tried to ground myself in the contemporary, English-language tradition of the genre: Stephen King (whose name has obviously loomed forever but whose work, aside from On Writing, I’d never really read), Thomas Ligotti (phenomenal, someone I hope to write about soon), Todd Grimson, Ramsey Campbell (cool in both senses of the word), Joe Hill (got a huge kick out of NOS4A2, though probably enough has been said about that book by now), Shirley Jackson, Dennis Etchison, Robert Shearman, Laird Barron, Bret Easton Ellis (crucial in his own way) … and Jack Ketchum.

Of everything I took in under these auspices, Ketchum’s The Girl Next Door hit me hardest. A few months later, it’s still in there, growing, helping me not forget that life’s a problem.

I could go on about its take on 60’s small-town American life and its amazingly apt and tender portrayal of boyhood and the loss of innocence and the rush of discovery when one’s own destructive urges first flare up, but what really tore this book into my lining was the surprising but inarguable way it distinguished the Banality of Evil (which everyone has) from something deeper, worse – call it the Uniqueness of Evil (which only some people have … or maybe they’re not even people at that point).

The premise, based loosely on a real crime committed in Indiana in 1965: a smart, hip NYC girl, Meg, and her disabled sister come to stay with their cousins and their freaky, bitter aunt in a New Jersey town after their parents are killed in a car crash. David, the narrator and boy next door, falls for Meg as soon as he meets her. Her worldliness, older-seeming-ness, the fact that she’s not a tiny-minded bigot … she doesn’t have to do much more than show up to introduce him to his “adolescence head-on.”

Things take their sweet, romantic time, all summery creekside flirtation and town funfairs, until Ruth, the sado-aunt, decides to imprison Meg in her bomb-shelter basement, claiming, in a fit of sanctimonious insanity, that she’s gonna teach the girl how not to be a slut and thereby spare her the grim fate of all women.

Thus the book enters its Banality of Evil phase, incrementally uncovering the dumb violence housed in Ruth’s sons and their neighborhood friends, David included: the way in which they all, horny and hopped-up on monster mags and hearsay, can’t resist the temptation of a hot girl chained and the freedom to lord themselves over her.

Under Ruth’s strict guidance, they torment the captive, dancing up to and back from the edge of sexual transgression, and torment themselves as well, wondering how far they’ll go, and how much it means to have an adult’s permission to go there … wondering whether going too far is inevitable or forbidden, and whether the deeper regret will prove to be doing or not doing the things they most want to do.

David hovers unstably between wanting to protect this girl he’s fallen for and wanting to relish the chance to see and touch her naked, to replace his normal teen fantasy with abnormal, unearned reality. “She was all I knew of sex,” he admits, “and all I knew of cruelty.”

Overcoming his initial revulsion and sense of wrongness, and thereby dismissing the only warning that could have saved Meg’s life because things are just getting started at this point, he stands by as “shame looked square in the face of desire and looked away again.”

All of this emotional development isn’t just the perfunctory “make the reader care about them so it’s scary when they get slaughtered” legwork. There’s something in David’s relationship to Meg and to the other, more easily unhinged boys, that rings absolutely true to the feeling of growing up and wanting to belong both to the species and to yourself, and to be one with your friends while also pursuing the things that take you away from them – both love and lust, doled out in equal parts tenderness and ferocity.

This whole Banality of Evil section is a masterpiece of denial and self-justification (and as good a Holocaust metaphor as I’ve seen), charting the ways in which David and the other boys combine permission and desire into a driving force that grossly trumps mercy. It’s as if the extremity of it all, the sense that it couldn’t be happening, excuses it, making it almost as though it isn’t happening, or at least promising that in retrospect, once they’ve had their fun and rite of passage, it won’t have happened for real.

January 13th, 2014 / 11:00 am

Prompted by Lily Hoang’s ‘On the Limits of Empathy, or, the Universality of Grief’

What struck me immediately after my dad died is that the grief I felt seemed simultaneously the most and the least unique feeling in the world: in its singularity no one could understand it; yet in its universality, to some extent, everyone could. I was comforted by this; by this sense that millions and millions of people have been in this situation and got through it. Time rolls on.

I find it interesting that in the therapy I’ve had since he died uniqueness and originality are subjects I’ve returned to again and again. Primarily, it has to be said, I’ve spoken about these subjects in terms of disappointment at realising that aspects of my personality I’d always thought were just completely my own are not really, after all, so unique. I don’t know what it might mean; perhaps it’s some sort of accounting I’m carrying out: what’s me; what was him etc? Perhaps, as well, I may just have sublimated the wanting of an original grief; that desire then emerging in another form? I find a possibility of truth in that. I realise I have a problem with grief: I feel guilty about indulging it. My dad dying was the terrible thing and that anything else might come close to causing me an equivalent level of pain – I mean even my grief over him dying – feels like something awfully hard to accept.

Last Thursday it was exactly four months since he died. I went to work; I sat at my desk; I talked to my colleagues; and I checked Facebook and my Gmail. I left at half five for an appointment with my therapist. The beginning of the week I’d felt very focussed on the coming Thursday; I’d expected it to be a tough day. As it turned out, for the biggest part of the day, it wasn’t tough at all. After seeing my therapist though things seemed totally to fall apart. I don’t know how to describe what happened other than to refer to those times a person feels hyper: a lot of energy; and, I guess, a kind of excitement at the things you might be able to do whilst in this mood; with it only slowly dawning on you that this excitement is a waste of time as this energy is directionless and impossible to focus. Well I had kind of the opposite of all that. There seemed to be a hyper-ness about how I felt, sure; yet instead of excitement featuring it absolutely was a down mood. And even now, two days later, I still don’t feel certain what happened: either I’d accessed something I’d tried to deny or I’d given one thing the name of something else out of a sense of dutifulness or, perhaps, a mixture of the two.

I wanted to tell my friend on Thursday about the significance of the day. I didn’t though. I wanted to tell it just as news but I was concerned, rather, it might come out as some kind of plea for sympathy. I’m not in a position yet to be able to assess the rights and wrongs of this.

This time last year I was involved in a brief relationship with a woman I’d met, in all places, via Facebook Scrabble games. I’d been playing online Scrabble for months – not in the hope of meeting anyone; just because I liked Scrabble – and opponents always seemed to be from London or Australia or somewhere; anyway, places very far away from where I live; this woman was from Stockport – just round the corner, effectively. Anyway, her dad had died some years earlier and she missed him very much; and she got it into her head that she wanted to meet my dad. As time passed this seemed to become more and more of a preoccupation for her; yet, it began to seem to me, more a kind of theoretical preoccupation than an actual one. What I mean is she liked to discuss meeting my dad yet never wanted to make any actual plans to that end. So the meeting never happened. She would always ask though, often even before she’d asked how I was, if my dad was okay. Since he died I’ve wondered on several occasions if I should get back in touch with this woman to let her know about my dad. I haven’t though. I think the occasions when I do consider this are times when I very much do want sympathy – and not necessarily perhaps for reasons connected to my dad. To use his death then as a means of acquiring that sympathy would feel very wrong to me.

Empathy is possible, absolutely. Regarding this idea of ‘genuine empathy’, well, if ‘genuine empathy’ is only possible between like and like I reckon it’s an idea that’s better off ditched. A person can understand and share another person’s feelings, sure; of course though they can’t access those same feelings in their particularity and uniqueness. Over these past four months I’ve been hugely grateful for the support of family and friends.

Since he died I have cried loads. The most recent time being last night at the thought of sorting through his clothes which I knew I’d be doing today. So far I haven’t cried today.

Tonight I will drink two cans of lager. Two because it’s that there are only two in the fridge. In the days and weeks following his death I drank loads and I drank all manner of stuff. The main reason for my drinking was, I think, because I just didn’t want to be at home – the home I’d lived in all my life with my dad. Drinking took me to the pub. It put me amongst people – alright, most of the time not people I was talking to (generally I’d be in the pub alone with just a book for company); it made that period between getting into bed and falling asleep last probably just minutes; drinking had a lot going for it. Today, mentioning to my aunt about the two cans I’d had last night as well, I realised something had changed: recently I’ve been drinking less.

About a month after my dad died the mothers of two friends at work died. Then the month after that the mother of a third friend died as well. I don’t think there were sky high expectations of me being able to prove particularly empathetic given what I was going through myself; and that was perhaps fortunate for me. Mike said to me though that people he would have expected a lot from at that time had, he felt, let him down; whereas people he didn’t expect so much from had really delivered. The reason for me saying this – I assume it’s clear – is that he felt I’d delivered. He meant, I think, I’d said stuff to him which was appropriate and which was useful. I’d found that easy to do though. As I said to him, perhaps I knew what to say because I’d so recently gone through this stuff myself. And that easiness is something I just don’t trust. It feels like due to it being so easy for me to know what to say what I said can’t have meant too much. Really, I mean, how useful are words? And I feel my sense of their uselessness takes something away from them even as I’m saying them. Still though, at such times words are often all we have to give.

How do we learn about death? We can learn about it from books, sure; but from books we’ll only take the generalities. Death in its horrible particularity is something we can only begin to learn about as we see those around us we love die.

***

Richard Barrett lives and works in Salford, UK. His poetry collections are Pig Fervour (Arthur Shilling Press, 2009); Sidings (White Leaf Press, 2010); A Big Apple (Knives Forks and Spoons, 2011); # (zimZalla, 2011); The Shangri Las (erbacce, 2013); with, forthcoming, Free (Blart Books, 2014). His work has been widely anthologized; most recently in Philip Davenport’s The Dark Would. He is a co-organiser of the Manchester based reading series Peter Barlow’s Cigarette.

Best Covers of 2013

As 2013 came to an end, everyone made lists of the best books of the year. Sadly, most of the lists published in popular sites (again, I said most, not all) focused on whatever came from the Big Five during the year and left out the gems that came from indie presses. Then the same thing happened with covers. I read/saw best lists covers at places like Flavorwire and The New York Times, and none of my favorite covers were there. Sure, there were a few good ones, but most were unoriginal, unbalanced, mediocre, etc. You know, fake ripped paper, bad photography, a few birds. I held a lot of covers in 2013, and most came from indie presses, so I decided to make my own list of best covers. Here they are in no particular order.

Sociopaths in Love by Andersen Prunty. The cover image by Dorothy Bhawl is great. Plus, a naked man riding an old stationary bike while wearing an elephant mask has to be on any cover list you make. Grindhouse Press publishes outré literature, and their covers let you know what you’re getting into.

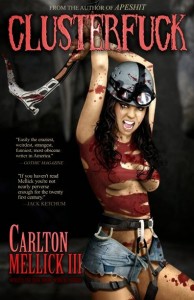

Bizarro superstar Carlton Mellick has made wise decisions throughout his career, and working with artist Ed Mironiuk is one of them. You don’t need to see Mellick’s name on a cover to know you’re looking at one of his book. As every year, Mellick released a few novels and they all had good covers. However, Clusterfuck gets the top spot because it reminds folks of Apeshit‘s cover, pays homage to all things 1980’s and gory, and because no one else out there has the guts to make underboob a recurring element in his or her cover art.

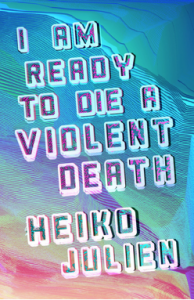

Michael J. Seidlinger is writing fantastic novels and editing/publishing top-notch literature over at Civil Coping Mechanisms. With whatever time he has left, he designs great covers. CCM covers are always different, and this year the best one was the cover for Heiko Julien’s I Am Ready to Die a Violent Death. It’s fun and wild and dirty, like a weekend in Vegas. Seidlinger is giving alt lit a look, and with the upcoming (June 2014) release of CCM’s 40 Likely to Die Before 40, and anthology co-edited by Seidlinger and Lazy Fascist’s editor Cameron Pierce and featuring work by Sam Pink, Scott McClanahan, Ana Carrete, Richard Chiem, Heiko Julien, Chelsea Martin, Megan Boyle, and many others, it looks like he will be doing it for a long time to come.

Chances are you haven’t heard of Dynatox Minitries yet. In 2014, you probably will. Author Jordan Krall started it as a project to publish limited edition books by neo-beat, neo-noir, horror, surreal, bizarre, and just plain weird authors he thought deserved a chance and weren’t getting one. It worked. Besides writing, editing, and publishing, Krall also does most of the covers, and some are as wild as the words inside. My favorite for 2013 is based on a painting by Krall and was designed for Randy Cunningham’s short story collection The Man With the Donald Sutherland Face.

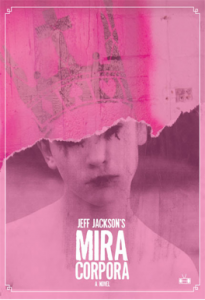

It seems Two Dollar Radio is doing everything right these days, and covers are not the exception. I loved the image on the cover of Scott McClanahan’s Crapalachia, but the best one this year has to be Jeff Jackson’s Mira Corpora. The color is unique and the art is eye-catching with a touch of creepy. Also, kudos to artist Michael Salerno for proving that with enough talent and drive, great things can be done with something as simple as a Flickr image.

Reading those rigged lists everywhere was hard for many reasons, but not seeing a Matthew Revert cover anywhere was insulting. Revert, who besides an outstanding designer is one of the best authors out there and whose novel Basal Ganglia made my list of best reads of the year, is the go-to man when it comes to eye-catching covers. Broken River Books, Lazy Fascist Press, Copeland Valley Press, Grindhouse Press, Dark Coast Press, LegumeMan Books, Swallowdown Press, and Raw Dog Screaming Press are some of the outstanding indie presses that regularly turn to revert for the kind of designs that sell books. Remember that famous cover that resembled a whisky’s brand and made Patrick Wensink a viral sensation? That was a Revert cover. Have you seen those recent books by authors like Jedidiah Ayres and Stephen Graham Jones that made Broken River Books the best thing to happen to crime fiction in 2013? All of them had Revert covers. All of Revert’s work deserves to be on this list, but I’ll give you the one for Pearce Hansen’s Street Raised and suggest you check out the rest of his work on your own:

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, journalist, and book reviewer living in Austin, TX. He’s the author of Gutmouth (Eraserhead Press) and a few other things no one will ever read. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Verbicide, The Rumpus, HTMLGiant, The Magazine of Bizarro Fiction, Z Magazine, Out of the Gutter, Word Riot, and a other print and online venues. You can reach him at gabinoiglesias@gmail.com.

Let’s overanalyze to death … Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart”

So far in this very irregular series, we’ve scrutinized Gotye’s “Somebody That I Used to Know” and Macaulay Culkin eating a slice of pizza—preparation for tackling one of the greatest and most beguiling music videos ever made.

“Total Eclipse of the Heart” was a single from Bonnie Tyler’s fifth album, Faster Than the Speed of Night (1983), and her biggest hit. It was written by Jim Steinman, Meat Loaf’s once and future collaborator. Steinman also planned out the video, which was then directed by Russell Mulcahy, a man responsible for numerous ’70s and ’80s music videos, as well as the films Highlander, Highlander II: The Quickening, and Blue Ice. So that’s the aesthetic world we’re dwelling in. (In a single word: overblown.)

The video itself is pretty broad, and rather easy to read—broadly. Simply put, Tyler plays an instructor (or an administrator) at an all-boys boarding school. (I will refer to her character as “Tyler” throughout, for convenience’ sake.) Extremely sexually repressed, Tyler endures a long night of the soul fantasizing about her young charges; this constitutes the bulk of the video. Come morning, she (and we) are returned to restrained, repressive reality. But we’re left with the hint that A.) at least one of her students has magically become aware of her fantasy, or B.) her fantasia has caused Tyler to become mentally unhinged. (I lean toward B and will defend that reading below.)

That’s the basic outline. The devil, however, sits in a straight-backed chair, clutching a dove. He’s also in the details, so let’s delve deeper …

Sunday Service: Matthew Henriksen

I Don’t Get Home Much Anymore

Cancer stink on interstates through Missouri and Illinois

No dreams induce sleep

Home

the word

represents

what’s closer to grass and trees

a mind away from smoke

The home I lived in

all the streets coordinate

paralysis in a shot of strychnine

Now I prefer stoned mountain roads

I live in a box in the mountains, yes

but my parents don’t cry in

their words there

I broke their mouths against my door

I locked myself inside with my daughter and her laughter

the shotgun I hold to my head

My light-crazed head

grins in the trees

shining through the window

I’ve been told to stop talking about light

To think money language

To think military-industrial complex squid children shudders

To drop drones everywhere

But light, friends, enters through the windows without breaking anything

Light makes the trees and light makes my daughter laugh

Not a weapon

my daughter

when the world is made of light

guns and money made of light, too

and everything made of light dissolves in light

salt in salt water

glows a thick light

Mind glows its own solution

Mind not like moon, not reflecting

But origin, a child

laughing when her daddy laughs

one bird laughing after another

I don’t go home

What fire alights has burnt out

What has resolved in its ash foundations hardly holds anything

A house will not stand after emptying

Places away from the disasters

let me breathe out

I open the door and let my daughter

run down sidewalks full of commerce

bio: Matthew Henriksen is the author of Ordinary Sun (Black Ocean, 2011) and a few chapbooks, most recently “Latch Down the Dark Helmet” (Wildlife Poetry, 2013). Recent poems appear in Toad Suck Review, N/A, Apartment, and Yalobusha Review. For Fulcrum #7 he edited “Another Part of the Flood: Poems, Stories, and Correspondence of Frank Stanford.” Since 2003 he has with Adam Clay co-edited Typo, an online poetry journal. He runs The Burning Chair Readings and works at the Dickson Street Bookshop in Fayetteville, Arkansas.