Conceptual Failure as Several Kinds of Success in Robert Fitterman’s Holocaust Museum

Holocaust Museum

Holocaust Museum

by Robert Fitterman

Counterpath Press, 2013

144 pages / $16 Buy from Counterpath or Amazon

In his book Notes on Conceptualisms, co-authored with Vanessa Place, Robert Fitterman states that “in much allegorical writing, the written word tends toward visual images, creating written images or objects, while in some highly mimetic (i.e., highly replicative) conceptual writings, the written word is the visual image.” He then says that “there is no aesthetic or ethical distinction between word and image” (Notes, 17). The reader tries (as a reader does) to make sense of this.

When a word is read or heard, its visual and sonic shapes activate the bodily memory of that word. This memory is connected to an image made up of a series of images (as all images are). There is no end to this series because it is by nature a series of series, infinitely referential. The “initial” series (the brain is so quick that we’re often completely unconscious of what images it is comprised of, or what we started off consciously thinking about) immediately births another series and this continues at a speed too fast for our fathoming, each series dropping out of another, until we hear or read the next word and the process starts all over again. This is brain vision (a written image), not visual vision (a visual image), and while the former is not any less vivid than the latter, there’s simply no denying that the two are, by nature, physically different experiences.

Fitterman is of course aware of this. But the goal of conceptual writing, as he later states, is failure (Notes, 22), and when a piece demonstrates the discrepancy between idea and execution—when what works in concept (for example, the written word being the visual image, rather than just referencing/conjuring it) reveals its artifice and deficiency in execution (the reader not experiencing the written word as, or in the same way as, the visual image)—it has been successful. In other words, the written word can, in highly mimetic writing, “be” (mimic, represent) the visual image within the writing (its conceptual framework), but it cannot literally recreate the experience of seeing (with one’s eyes) the visual image it is referencing. This is one of the reasons why Fitterman’s conceptual project, Holocaust Museum, is successful at what it does.

Holocaust Museum definitely qualifies as a “highly mimetic” or “highly replicative” conceptual work. The book is divided into seventeen sections—Propaganda, Family Photographs, Boycotts, Burning of Books, The Science of Race, Gypsies, Deportation, Concentration Camps, Uniforms, Shoes, Jewelry, Hair, Zyklon B Canisters, Gas Chambers, Mass Graves, American Soldiers, and Liberation—all of which are titles of actual exhibits at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.. Each section, accordingly, consists of captions that correspond to actual photographs (which are not shown, just cited by title) featured at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. The scenes described by the captions greatly vary in almost all senses—location, who or what (objects or people or a combination of the two) is pictured, action or lack of action, the level of brutality in such, implicit and explicit violence, etc.—but each caption explicitly relates back, in subject matter, to the title of the section in which it’s included.

In its most basic conceptual sense, Fitterman has made a Holocaust museum completely out of words. What makes this so is that the words are working exclusively as representations of images. What makes this work successful, in one sense (the conceptual sense), is that it fails by its very nature (as a piece of writing) to recreate the visual images its captions stand in for, as well as the inherently different experience of seeing a picture, rather than having it described to you. What makes this work successful in another sense is that the effect of reading the captions devoid of their photographs is incredibly haunting, and is so in a way that lacks familiarity to us (“We have seen the pictures of our past, but the point is the caption” – Vanessa Place, on Holocaust Museum). The language of the captions is sterile and simple, even in its depiction of absolute atrocity (“View of the door to the gas chamber at Dachau next to a large pile of uniforms. [Photograph # 31327],” Holocaust, page 61), and as witness to these depictions, the reader begins to, in a sense, read the language, the voice, as their own, feeling increasingly implicated as they move through the text.

With Holocaust Museum, Robert Fitterman has made a conceptual object that succeeds by his own standards of success (failure, specifically in its ability to replicate) as well as by a more mainstream literary standard—being evocative, haunting, innovative, and generally affective. This is one way for a work of art to be exceptional, and with its confrontation of an event as important, disturbing, and already-discussed as the Holocaust, Holocaust Museum proves itself to be a groundbreaking and extraordinary conceptual work from several angles.

***

Lily Duffy is a poet, teacher, and editor living in Denver while working on her MFA in poetry at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her writing has appeared in the Baltimore Sun, Baltimore City Paper, Hot Metal Bridge, ILK journal, Cloud Rodeo, Bone Bouquet, NAP, inter|rupture, and elsewhere. With Rachel Levy she co-edits DREGINALD.

March 31st, 2014 / 10:00 am

SOS: Songs of Solomon: A Queer Translation

SOS: Songs of Solomon: A Queer Translation

SOS: Songs of Solomon: A Queer Translation

by j/j hastain

Spuyten Duyvil Press, 2013

208 pages (photography and text) / $40 Buy from Spuyten Duyvil or Amazon

How to speak of j/j hastain’s SOS: Songs of Solomon: A Queer Translation? There will inevitably be as many experiences of SOS as there are readers of it. Perhaps, for some of us who decide to fully enter the dimensions and matrices of SOS, witness will end up being a more proper term than reader. As a reader/witness, it is hard to come away from this physical object—a thick, hybrid intersection of photography and fierce poetic meditations about loves, genders, sexualities, spirits—without having felt invited to project oneself into it. In addition to a book, SOS is a hand, potentially open, filled with secrets about bodies and beloveds. If you allow yourself to be love-filled and tender as you hold your hands open in return, from the other side of the book/body, you could receive a secret. “All this love in order to be part of the incarnate, sentient language wherein grief and fulfillment no longer need to be at odds with each other.”

hastain summons witnesses with the second person tense throughout: “Perhaps intimacies within a book obsessed with the beloved can lead you to your beloved in form? Would you be forlorn during each of the necessary translations?” Translation from book to body. From body to beloved. The beckon of the beloved as friend, lover, self, secret, reader; beloved as witness; beloved as an act of shamanistic return. “It makes you beloved to me that you can hear my interior echoes.”

I’m just one of the reader-witnesses of SOS, and there’s no way of knowing what manifestations of SOS I haven’t accessed but that you, or you, or you might discover and decide to navigate on your own. I find this wonderful. SOS leaves spaces in which the told and untold point to each other deliberately and with care. Many of those spaces exist between the words and the photographs that tattoo the book/body’s paper-skin. SOS is decidedly mystical, written on itself with images of disjointed body parts, dreamscapes, and various unspecified holdings. Its words and images weave ribbon-like through countless definitions and enactments of love—love as fear, as ecstasy, as spirit, as sexual practice, as ancient elements, as “gender from the ground up”. This book/body resolutely invites, sometimes implores, the “you” into the profound, open-ended environments of genders.

All these bound ribbons and their inverse liberations sing, draw out, mourn, and dance. They carry each other through countless modes: The sexual—tongues; skins; “an infinitude of virginities and coituses”. The earthly—birds; gems; sky-myrrh; “this one handful of water that I’m carrying”. The mystical and psychospiritual—“non-singular states in the spirit of confession”. No dance here can be disconnected from its Others. I experience SOS as both a home and a mystery—not a mystery to be afraid of, necessarily; a mystery that can be learned from, one that needs light here and darkness there, sometimes on its own terms and sometimes via the willingness of the “you”, of the beloved, to touch it. It is hard to escape the conclusion that the decision to be alive in this manner is a marvelous and worthwhile decision for a book to make.

***

Carolyn Zaikowski is the author of the novel A Child Is Being Killed (Aqueous Books, 2013). Her poetry, fiction, and essays have appeared in Pank, The Rumpus, Eleven Eleven Journal, Sententia, 1913: A Journal of Forms, Nebula: A Journal of Multidisciplinary Scholarship, Everyday Genius, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Naropa University. She can be found at www.liferoar.wordpress.com.

March 31st, 2014 / 10:00 am

Sunday Service: Ashley Opheim

Killin’ It

Candida, candida,

I soak a tampon in apple cider vinegar and push it up my

lavender candle, lavender candle.

Tilikum, Tilikum,

people do awful things to make money in the name of entertainment.

Sea World is a fucking horrible place.

Entertain me, entertain me,

soft world.

Fuck Sea World.

Are you captive in a place just a little bit larger than your body?

I fall into a very deep thought about the conditions of vanishing

in the well-lit, but not too well-lit change room.

I buy fluoride-free toothpaste because I’m trying to

activate my pineal gland.

Some people say evil people who work for powerful people

put fluoride in the water because it dumbs you down.

Candida, candida

I am self-medicating with pure cranberries and apple cider vinegar.

I buy chocolate eggs and tea light candles.

Everyone’s tongue is pink la-la-la.

I am craving sugar so much.

Candida, candida,

I do mountain pose in yoga and kill it.

I kill that pose.

I dream that I dance with Beyonce on AstroTurf.

I kill that dream.

I dance like the best I’ve danced ever.

I sip my cell phone, mistaking it for a glass of water.

I breathe out of my ears.

Bio: Ashley Opheim (Ashley Obscura) is the author of the poetry collection I Am Here. She lives in Montreal, where she is the founding editor of Metatron and co-director of the reading series This Is Happening Whether You Like It Or Not. She can be followed on Twitter @hologramrainbow.

“My Cat Had To Have His Penis Cut Off:” An Interview with Dustin Long

Shane: Can you talk about what’s happened since we last spoke?

Dustin: Well, you were pretty much spot on with your predictions: Bad Teeth got picked up pretty soon after we spoke; Pavilion hasn’t been so lucky, though I’m not actively trying to sell it. I realized a little while ago that I want to make some revisions and additions to it, which I plan to get to as soon as I put the finishing touches on a third novel I’ve been working on.

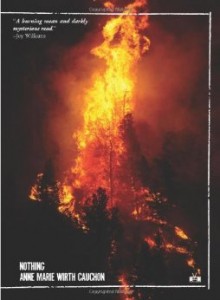

Nothing by Anne Marie Wirth Cauchon

Nothing

Nothing

by Anne Marie Wirth Cauchon

Two Dollar Radio, Nov 2013

178 pages / $16 Buy from Amazon

“The question is how much reality must be retained even in a world become inhuman if humanity is not to be reduced to an empty phrase or a phantom. Or to put it another way, to what extent do we remain obligated to the world even when we have been expelled from it or have withdrawn from it?… Flight from the world in dark times of impotence can always be justified as long as reality is not ignored, but is constantly acknowledged as the thing that must be escaped.” — Hannah Arendt, On Humanity in Dark Times: Thoughts about Lessing

Mrs. Wirth Cauchon’s novel Nothing confronts us with a startling self-portrait, at least for my generation. All who cannot see a part of themselves in this story simply have not been paying attention. Her narrative concerns the exploits of two young women and one young man whose lives intersect in bizarre and serendipitous ways in the modern American West, a place of danger, intrigue, and darkness, but also of an earthy, natural vitality. The setting is deliberately emphasized and plays a vital role in the plot, but it by no means confines the story, for like all good stories, it explores the being of people in the world.

Why so lost? Why such dark times? Our dark times consist not so much in the active persecution and expulsion from the public realm that were the hallmark of Ms. Arendt’s, but instead the “irreality” of politics that attends our own. James, Bridget and Ruth are all expelled from the public realm into merely personal society and suffer tremendously for it. In the absence of anything in particular to do, their personal quests metastasize into monstrous projects all out of proportion to their potential payoff. These are the conditions in which we find them, and the results are fascinating.

Of the three, James has the most tangible quest, to find out the “truth” about his father. As he makes his way to the book’s setting in Missoula, Montana there is an evident relish in the manner in which he chooses to convey and conduct himself that belies his deeper nature. He doesn’t want to find out about his father, he wants to be a guy who wants to find out about his father, one whose very nature is consumed by this oh-so-meaningful project to the degree that he will endure any discomfort to see it accomplished. He wants to embody passion, to demonstrate it to the world in such a way that he will be recognized for it. Why this perversion of a straightforward quest? It tips us to the conditions in which he operates, a sneaking suspicion that the world around him has grown cold and flaccid. His is a demand for hardness in a soft world. To him, his step-father embodies this tendency toward dissolution. He is what society expects him to be and nothing more: quiet, respectable, financially-successful. He lives up to his end of the social contract that offers no great reward, but also no great risk. James wants to be a conqueror, not a sober merchant, in a world that offers little of value to conquer.

Hardness he seeks and hardness he finds. When James locates life’s crueller edges he beats a partial retreat back into the world of softness where he finds Ruth. He will discover that she too has hard edges. Their inability to communicate effectively, to understand one another sympathetically, undoes them both. It seems so odd at points, this inability, but is it not a habit that we have done a good deal to disburden ourselves of? Our world moves at a speed and a level of self-absorption that is conducive neither to quiet contemplation nor thoughtful dialogue. What we cannot digest in thought, we vomit at one another. Ruth and James unravel as quickly as they fell into one another, bound together ultimately by as much nothing as surrounds them.

March 28th, 2014 / 10:00 am

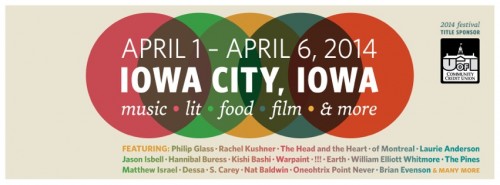

Mission Creek 2014 and all its Art, Film, Music and Lit is almost upon us with Phillip Glass, Rachel Kushner, The Head and the Heart, Warpaint, Brian Evenson, etc.

***

And this year HTMLGIANT will be part of the Litcrawl (Friday, April 4th) where Colin Winnette and Grant Maierhofer will read from their work featured on HTMLGIANT as part of an “Electronic Literature” event at The White Rabbit.

***

(The Iowa Review, Red Hen Press, Hobart, Spork, Black Ocean and others will also be a part of the Lit Crawl.)

***

Go here for full calendar

25 Points: Is It My Body?

Is It My Body?

Is It My Body?

by Kim Gordon

Sternberg Press, 2014

182 pages / $18.86 buy from Amazon

1. Kim Gordon the New York City artist is one and the same with Kim Gordon, bassist of Sonic Youth.

2. Despite her claim, “I don’t think of myself as a musician,” whether they’re “on hiatus” or not, the band’s music remains the central association by which readers are likely to recognize her name.

3. I’m no diehard fan of Sonic Youth. Although I do, after a fashion, dig their music and several years ago saw them play The Crystal Ballroom in Portland, OR.

4. This is no tell-all. Sonic Youth is more an afterthought than anything here, a near excuse to remain creative—though no less central to Gordon’s life.

5. Gordon’s reasoning for taking part in Sonic Youth: “Being part of a music culture or subculture appealed to me more than staying outside and commenting on it in a work of art.”

6. This book zooms. It’s a sonically charged brain charge; a light breeze to read yet nevertheless heavily informative. Contents range from Gordon’s first published texts from the early 1980s rather seamlessly on up to a conversation she had with sometime-fellow collaborator Jutta Koether, not even a year ago.

7. Gordon skirts the edges of official art gallery/curator talk, usefully dipping into its discourses only to flaunt her independence from reliance upon them to express her thoughts. While postmodern, avant-garde, theory-driven vocabularies and accompanying ideas are occasionally floated and tussled with, they’re smoothly exited from without distracting from the natural style of her writing.

8. Gordon tells of only useful and/or interesting things, both historical and eternal.

9. “One of the appeals of seeing No Wave bands in New York early on was that it was such a strangely abstract music. It was very free and very abstract. If you didn’t have any means to enter the galleries as an artist, being in a band was a way to be expressive and be independent of the gallery system.”

10. Unedited: “How many grannies wanted to rub their faces in Elvis’s crotch and how many boys wanted to be buttfucked by Steve Albini’s guitar?”

March 27th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

POEM-A-DAY from THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN LUNATICS (#16)

Tara Atkinson is a writer in Seattle. She is one of the founders of APRIL, a festival of small press and independent literature. Her chapbook, BEDTIME STORIES, is available from Alice Blue Books

for Those

About to Order

by

Tara Atkinson

![]()

It’s a story in sheep’s clothing. // I had permission to take video of some sheep, but I jumped the wrong fence. // This was actually the first bedtime story I wrote, at least a couple years before the collection was going to be a thing.

It’s a story in sheep’s clothing. // I had permission to take video of some sheep, but I jumped the wrong fence. // This was actually the first bedtime story I wrote, at least a couple years before the collection was going to be a thing.

![]()

note: I’ve started this feature up as a kind of homage and alternative (a companion series, if you will) to the incredible work Alex Dimitrov and the rest of the team at the The Academy of American Poets are doing. I mean it’s astonishing how they are able to get masterpieces of such stature out to the masses on an almost daily basis. But, some poems, though formidable in their own right, aren’t quite right for that pantheon. And, so I’m planning on bridging the gap. A kind of complementary series. Enjoy!