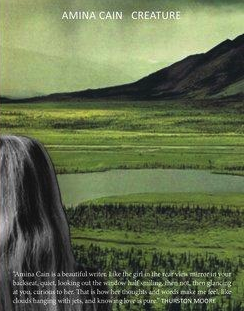

I write to see what is inside my mind: An Interview with Amina Cain

“I’m not sure why I’ve written so many flat male characters. I think it’s more that I have wanted to pay attention to the female characters and so I have.”

Kate Zambreno first changed my life when she wrote Heroines, and second when she wrote on her Facebook page that she can’t wait to read Amina Cain’s new book. I read Creature as soon as it was released and it also changed me, but in a familiar way. I felt instantly connected to Amina’s writing and her characters in particular—the first person narrative, the painted landscape of the mind, the abstract settings. I had only discovered Clarice Lispector a year before, and I felt a resonance between the two. Part of the reason I love Lispector’s writing so much is her ability to reach so far into her characters’ psyches. Amina Cain, in a completely different way, also reaches into her characters’ psyches. Amina’s way feels much more meditative and connected to the earth. Lispector is often very much “above” the earth. Amina’s stories are mysterious, full of curiosity, and very dark and then suddenly extremely funny. When I saw the name Clarice used as one of the character’s names in a story, I knew it was no coincidence. I also knew I had to contact Amina Cain immediately.

Kate Zambreno first changed my life when she wrote Heroines, and second when she wrote on her Facebook page that she can’t wait to read Amina Cain’s new book. I read Creature as soon as it was released and it also changed me, but in a familiar way. I felt instantly connected to Amina’s writing and her characters in particular—the first person narrative, the painted landscape of the mind, the abstract settings. I had only discovered Clarice Lispector a year before, and I felt a resonance between the two. Part of the reason I love Lispector’s writing so much is her ability to reach so far into her characters’ psyches. Amina Cain, in a completely different way, also reaches into her characters’ psyches. Amina’s way feels much more meditative and connected to the earth. Lispector is often very much “above” the earth. Amina’s stories are mysterious, full of curiosity, and very dark and then suddenly extremely funny. When I saw the name Clarice used as one of the character’s names in a story, I knew it was no coincidence. I also knew I had to contact Amina Cain immediately.

***

LW: When did you start writing?

AC: I began writing during my last year of college. I started out as an acting major, which I quickly gave up, switching to Women’s Studies. I knew I wouldn’t necessarily do anything specific with this major, but I was interested in the classes. Then, when I took my first creative writing workshop, I knew I had found what I wanted to do with my life.

from the film adaptation of Hour of the Star

There are many references to Clarice Lispector in your work and in your story Queen you quote from The Hour of The Star: “forgive me if I add something more about myself since my identity is not very clear, and when I write I find that I possess a destiny. Who has not asked himself at one time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?” When did you first discover Clarice Lispector? Would you say you connect similarly to her themes of the metaphysical experience of “finding yourself” through the process of writing?

I relate very much to the idea of finding oneself through writing, though what “oneself” is I think is malleable. And that Buddhist idea that to study the self is to find the self and to find the self is to lose the self resonates a lot for me. I’ve been curious lately about why I am so driven to write first person narratives (that are both not me and me) as opposed to third person, for instance. It’s not that I want to tell a story of myself, or even of another, it’s that I want to inhabit something—some feeling, some space (physical or psychic, and yes, even just the space of writing), or voice, and the first person, for whatever reasons, allows me to do this in the strongest way. I certainly think that Lispector’s fiction does this too, much more so than simply telling a story. She creates these charged psychic spaces we can walk into as readers. I first read Lispector the second time I lived in Chicago. I checked out from the library Family Ties, a collection of short stories. Then The Hour of the Star.

So many of your stories seem to be about a central narrator. They can be separate and yet they feel a part of a continuous story. Can you talk about the narrator of your stories? Do you consider her a persona? Do you see her as existing in each of your stories? Or is she different, a new character, each time?

I see the narrators in Creature as different beings but as sharing a single heartbeat. I wanted them to be both separate and connected. In Tisa Bryant’s amazing Unexplained Presence a beautiful continuum comes into being, or else a soft light is shone on connections already present between people who existed throughout time but never knew each other, or even knew to know each other. I was so struck by that when I first read Bryant’s book, and I think the idea of the continuum has stayed with me since, though of course in a different way.

There is a quality of bleakness to your characters, or to quote from one of your titles, “a threadless way” about them. They are very honest about the fact that they don’t know what they are doing or how to connect to others. (And yet, because of this, they do know—like what you were saying about finding the self to lose the self, etc.)

This is a sharp contrast to what we are used to seeing in a lot of contemporary literature. (Of course, “flawed characters” are everywhere—but usually they don’t know they are flawed and when they do, their revelation is fleeting or they step into denial.) Your characters have the ability to speak, feel, and live out their insecurities, distastes, annoyances, melancholy, and this gives them a strange hopefulness and positivity.

I think that most of my characters are searching for something, are always in process with the world around them, and that much of what gets expressed in the stories are the things that are usually not said, supposed to be said, voiced. In fiction, I’m as interested in an inner life as an outer one, and I want to write that life. I think it can propel a narrative forward as much as plot can. There is drama there, and conflict, and relationship, and even setting. I’m glad that the characters feel hopeful to you. Sometimes there is a focus on the sadness and vulnerability in my stories, elements that are certainly present, but to me there is also absurdity and humor. READ MORE >

Melissa Broder would like to offer you these new poems, handwritten, made with love and gifs. Read them online, analyze not just the words but the penmanship.

“I had a thing of words, and now they’re gone”

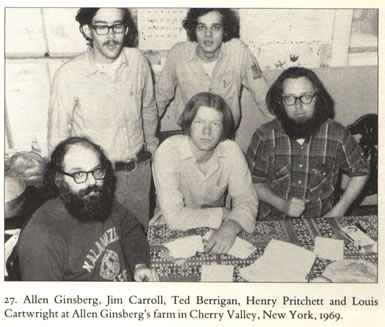

Forced Entries: The Downtown Diaries 1971-1973

|

Forced Entries: The Downtown Diaries 1971-1973

by Jim Carroll

Penguin Books, 1987

196 pages / $15.00 buy from Amazon

Rating: 8.0

|

Although The Basketball Diaries was blanched by LEO, High School English, and pop revisionism, Forced Entries, Jim Carroll’s 1987 follow up still has a lot of charm.

Subtitled The Downtown Diaries 1971-1973, this book tackles the emergence of the lost and romanticized Downtown scene. As a poet, Carroll was active in readings at St. Mark’s Cathedral and a Warhol Factory regular. It’s a short book, under two hundred pages, and it’s framing as diary entries allows Carroll a soft touch as he relates observations and anecdotes.

June 17th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

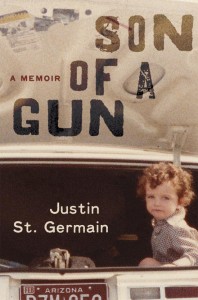

A Well-Lit Memory: Justin St. Germain’s Son of Gun

Son of a Gun: A Memoir

Son of a Gun: A Memoir

by Justin St. Germain

Random House, 2013

256 pages / $26 Buy from Amazon

As I read Justin St. Germain’s memoir Son of a Gun, I began circling all the times I came across the words “I wonder”: “I wonder why he never tried to call me, if he was ashamed, if he thought I was”; “I wonder where it is now, if she lost it, if I left it behind in the trailer”; “I wonder if she told him to say that, trying the same trick that worked on the judge who dismissed my case.”

The blurb on my copy’s back cover compares Son of a Gun to The Liar’s Club and This Boy’s Life, and while there’s certainly a likeness, St. Germain’s story isn’t so much as coming-to- age as it is remembering the moment he did—piecing together the events that led his step-father, Ray, to murder his mother with a shotgun.

At a cemetery, when St. Germain and some of his extended family fly to Philadelphia to bury Barbara, he mourns not the passing of his mother but the passing of his memory:

She fades a little more each day: I can’t picture her face, can’t remember a time when she was alive. I don’t know her story, because I’ve tried to forget, and because there was so much I never knew… Nearly a decade now since she died, and all that’s left of her are a few relics and my own suspect memories.

St. Germain opens, though, with perhaps the clearest memory he has: the afternoon he learned of the killing. Riding his bike home, he stares up at the expansive Arizona sky. It’s only been “nine days since the towers fell,” and he’s “newly conscious of planes.” When he arrives at his house, his brother, Josh, tells him the tragic news: “‘She got shot.’”

At a bar later that night, unsure of what to do next (“‘Wait, I guess’”), St. Germain drinks with his friends, watching President Bush address the nation on television: “He said that life would return to normal, that grief recedes with time and grace, but that we would always remember, that we’d carry memories of a face and a voice gone forever.”

Remembering “a face and a voice gone forever”—rounding out his “own suspect memories”—is what St. Germain hopes to solidify ten years later through his writing, and his struggle is not one of coming to terms with the tragedy (who can ever do that?) but of realizing that his recollections, his “truth” about his mother’s life, is what’s most important. That he starts with her death—that when he hears about what happened he doesn’t experience “shock” or “grief” but rather “a recognition, as if [he] had always known this moment would come”— presents an apparent contradiction: that one of his most vivid memories was formed even before it materialized.

Growing up in New Jersey, not far from Manhattan, most people I know can say what they had been doing on September 11th, while many also claim a counter-narrative, what they should have been doing, what they weren’t doing: they missed work because of a last minute disease; they didn’t get on one of the flights because of traffic; they decided not to take a day trip into New York that morning. I always thought there was a slight self-centeredness to such thinking—it could have been me, but wasn’t—and likewise, invoking such a large concept at the start, his mother’s death in the wake of 9/11, runs the risk of the same solipsism. St. Germain, however, does this so skillfully and so deftly that he’s completely changed my thinking, especially on the first matter. It’s not a selfish act for the could-have-been-victims of the terrorist attack to imagine if it had been them, or a loved one, or somebody they knew; instead, it’s a way to try and make sense of something insensible, even if it’s not completely shocking, or even, perhaps, if it’s already been there as a likelihood in one’s mind all along.

June 16th, 2014 / 4:30 pm

The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World by Brian Allen Carr

The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World

The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World

by Brian Allen Carr

Lazy Fascist Press, May 2014

128 pages / $9.95 Buy from Amazon

Brian Allen Carr’s The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World is a bewildering book—a work of low-key madness. It’s a novel that moves across literary modes—from horror, to gritty realism, to psychological study—without ever quite embodying any one. In his introduction to the novel, Tom Williams compares the novel’s genre-confounding qualities to the border between Mexico and Texas, where Carr lives: “the border that exists between the fiction deemed as literary and that deemed as genre is far better policed and regulated than the border between Mexico and Texas.” You, like me, might be skeptical of such a claim—if anything, the Jonathan Lethems and Gillian Flynns of the world seem to suggest that the border between literary fiction and genre fiction has worked out a pretty decent immigration system—but Williams’ point still resonates: Carr’s novel is difficult to categorize. If anything, the idea of just one border is too reductive here: The Last Horror Novel feels, perhaps, like a dispatch from the four corners of the American Southwest, with Carr standing upon the intersection, dipping his foot into each of the states for only a second at a time.

Carr’s novel takes place in the evocatively named Scrape, Texas. Seriously, you know exactly what this town is like without me—or Carr, for that matter—describing an inch of it. Scrape is a “blink of crummy buildings, wooden households—the harsh-hearted look of them, like a thing that’s born old.” In this town, young and old alike seem stranded. The denizens drink beers, sleep with one another, and antagonize other races. A young woman like Mindy was lucky enough to get north to Austin for college to engage in artistic revelry, attending screenings at the cinema and falling in love with art films, but life blew her back like dust to Scrape. She and a handful of other characters—including racist Burt; his buddy, Manny; Tyler, the victim of Burt’s racism; jerk-off Tim Bittles, with his dick pics and “cell phone titties;” Teddy and Scarlett, who spend the novel either pre- or post-fucking; Blue Parson and Rob Cooder, who just want to drink beer all day; and convenience store clerk Tessa—wander through the town, working, killing time, and making secret their bouts of herpes.

A great boom—massive, shattering—changes this, and “newscasts show static.” Burt says, “Something’s off,” and he isn’t kidding: for reasons Carr never attempts to explain, horrors have been unleashed upon the town of Scrape. First, there is La Llorona, “the Weeping Woman,” a ghost that gathers replacements for the children she drowned. Then, there is the “fuzzy hand, the Devil’s hand, the black hand, the hand of Horta,” which brings violence and death to the world of the living. In short, the town of Scrape—full of small town American decadence—is assaulted by the myths of Mexican culture. And the residents of Scrape, in true American fashion, respond by fetching their guns and shooting without thinking.

This is a “genre novel,” yes, but not in the way most mainstream readers would expect. Instead, it’s a “genre novel” in a way that most literary/Alt-Lit readers (and readers of HTMLGIANT, certainly) will be comfortable with. By that I mean, it fucks shit up enough to be interesting, but doesn’t delve deeply enough into genre to be deemed boring. Early in The Last Horror Novel, Carr signals his generic divide while describing Scrape as being positioned between “two legitimate cities”: Corpus Christi and Houston. Carr’s novel, therefore, occupies an illegitimate space—not too different, really, from the so-called “illegitimate” space that genre fiction occupies. For instance, Carr flirts with one of the great tropes of the Victorian gothic: the notion of the “gentlemen’s club,” i.e., men of science, sitting around, discussing things that science cannot explain. Gothic tales tend to rely upon the unutterable: how, after all, to describe the uncanny happenings of the world? In this sense, Carr’s novel feels like old-fashioned horror: his characters huddle, attempting to explain the unexplainable. A rickety tree house becomes Carr’s version of the “gentlemen’s club.”

This is a short novel, and Carr’s style is elliptical and spare. A recent work of fiction like Katherine Faw Morris’ Young God comes to mind, though Carr is far more playful. Maybe the stripped down prose of Brautigan is the more apt analogue, and Carr’s cultural commentary seems to operate a bit like Brautigan’s: he embodies a milieu so fully that he winds up satirizing it without expending a single extra breath. Many of his chapters are just a few paragraphs, and the book’s already trim 121 pages contain a lot of white space. Within this small frame, Carr moves through literary modes that go beyond genre, from the dirty realism of Scrape, to a section labeled “Thoughts” that becomes psychologically probing and revealing in a way that nothing else in the book is. Then, in this novel of jagged edges, there’s an additional piece: a first-person voice that floats through the text—something between Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides and Joan Chase’s During the Reign of the Queen of Persia, though lacking either novel’s coherence.

Does all of this add up? No. Is it supposed to, or does it need to? On those points, I’m less certain. The end of The Last Horror Novel sort of dissolves, crumbling in the reader’s hand—but then, when unspeakable horror is unleashed onto the world, what other possible ending is there aside from gradual dissolution? This fatalism makes Carr’s novel feel emotionally muted but brief enough for this not to matter; it is, after all, closer to a long short story or novella than anything else, and as a result, Carr works out one idea and produces interesting results. It may not seek emotional complexity, but it’s effective in its portrait of characters that think themselves at a dead end. Ultimately, Carr is ingenious in externalizing this existential angst by deploying the conventions of a genre. There’s an apocalypse coming to Scrape, Texas, and Carr seems to be saying, “You think your life’s at a dead end? You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

***

Benjamin Rybeck is events coordinator at Brazos Bookstore in Houston. He writes for Kirkus Reviews, and his work also appears or is forthcoming in Electric Literature’s The Outlet, Ninth Letter, PANK, The Rumpus, The Seattle Review, and elsewhere. His fiction has received honorable mention in The Best American Nonrequired Reading and The Pushcart Prize Anthology, and he is currently seeking an agent and/or publisher for a novel and a short story collection.

June 16th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Lisa Ciccarello

from Don’t be like that.

From behind the tree you can see her mouth. She can see you & the mouth says help me. You could. There is a basket, a blanket, a skirt.

You think of the field stripped beneath the power lines. You return with scissors.

A light shines on slices of wood. A light shines when you shut the door. You use the branch to cover the mouth.

*

& the blanket spread beneath them. Truly, they don’t know yet what they are weeping for. The sound of stone on skull is like a kind of crying: everyone closes their eyes.

He puts a chocolate in each hand, loose but useless. When he looks at them, he sees himself.

It was bound to happen, you know. It was only natural.

*

They are going to lie a long time now.

What you’ve done so far, you’ve only done to their bodies. They have one last place left in them to reveal to you. Little by little they remove the dress of your grip.

They do not go very far.

Bio: Lisa Ciccarello’s first book of poems, At night, is forthcoming from Black Ocean. She’s the author of several chapbooks, including Worth Is the Wrong Word, recently out on Black Cake Records. Her poems have appeared in Tin House, Denver Quarterly, PEN Poetry Series, Handsome, Poor Claudia & Corduroy Mtn., among others. She edits poetry at draft: The Journal of Process.

Whas’Poppin: 6/13/14

OK, we spend a shitload of time talking about books in this piece and just about absolutely no time talking about all the free-ass online “content” (LOL) that exists in the world and that seems weird and absurd considering that me and 3.7% of you wallflowers used to read this thing (and other things) in Google Reader and now that’s not a damn thing anymore but you’re a thing and I’m a thing and the follow lines are the thingiest things I got googly-eyed over this week yanawahmean.

——–—

I.

The law does not say sorry. The law says get inside with our skin but do not leave home without it.

Gina Keicher, “Naked On The Internet” (Birdfeast)

II.

I will also admit

how moved I am

by instrumental versions

of terrible songs

in restaurants and that

I’ve never understood

why at the end

of the nightmare

the murderer and I

eat a meal together.

Anne Cecelia Holmes, “If You Ask I Will Tell You” (Sink Review)

III.

If toilets flushed forwards

there’d be more poets.

-John Ebersole, “Until My Stomach Is A Microchip I’m Not Impressed” (BOAAT)

IV.

a new myth in which my hands are put down

at the wrist. where the bone is cut off at the elbow

and thrown to the hounds. a new constellation

where a boy drags his dead dog across the night sky.

-Sam Sax, “Hands” (Smoking Glue Gun)

V.

Perhaps I cry because I can’t believe how much there is

that I don’t believe in

Whatever I am, please look later

-Monica McClure, “Skunk Hour” (GlitterMOB)

———-

Oh boy and check out the new issues of Anti- because the whole this is just whoa.

The Opening Pages of Joshua Corey’s “Beautiful Soul: An American Elegy”

Available now from Spuyten Duyvil

Because my home office has stacks on stacks of books, because new books are added to the stacks almost daily, because I have not finished half of half of the books I’ve started, I cannot grant attention to more than the opening pages of a book before I decide whether or not to stick with it. In truth, if a book has not convinced me within five or six pages that it deserves my complete attention I put it in the box labeled “To Be Traded At The Bookstore in Jacksonville.” Sadly, many many books end up in that box. Given the limited number of books that escape such a fate, I thought I might spotlight a few of them this summer in a series I’m calling “The Opening Pages.” Could have also called it “Books that didn’t end up in the trade box,” but that sounded less catchy.

Joshua Corey’s Beautiful Soul: An American Elegy did not end up in the trade box. Quite the contrary. I think it’s one of the most interesting and impressive books I’ve read lately. And since it has just been released, I thought it would be a great place to start this series.

The Real-Time Review League reads nods by Carrie Lorig

nods

nods

by Carrie Lorig

Magic Helicopter Press, 2013

48 pages / $7 Buy from Magic Helicopter Press

July 25, 2013

Kelin,

I read through the first half of nods., like we said. I’m happy to be doing it in two pieces, as the book leaves me a lot to process.

For me, what comes first here are impressions. Looking into the dark and seeing shapes, but waiting for your eyes to adjust before you can make out bodies and what they are doing.

I read the first “Scatterstate” and thought, if I had to define this term, it would be:

scatterstate: noun, immersion in repetition and variation of words; a swelling up of words, which become, in addition to their actual definitions, their sounds and the feeling of hearing/thinking them over and over; an inundation

When it is too much to think about, I am left with hearing and feeling and drawing conclusions from those sensations. And because of THE PAGE and her use of space on THE PAGE, sometimes it is too much. I think she knows this. Because it’s not like eating too much ice cream; it’s like tumbling down too much mountain, or hiding under too many houses. It surprises and excites me, too, when out of this inundation, narrative is born, which happens here.

So much here depends on unlikely pairings of words—sometimes as separate, paired words, and sometimes as compounded words. A few of my favorite compounds from p17: “mangovault,” “niagarafalafel,” “boozyoveralls,” “meatbowl.” This chapbook asks us to wonder, what happens when you push two, separate, unlike things together? How do we make sense of that? And in that way, it is a painstaking immersion in the messy business of sex and love. Preparing to leave for a long vacation without Phil tomorrow. I want to go and I don’t want to go. It feels, sometimes, like we are always orbiting the same thing, but at different rates. I’m being dramatic—everything is fine, of course, we’re very happy. But love is never easy or clean.

Last night we ate waffles filled with curried chicken from a food truck. It makes me wonder, if waffles can be a vehicle, what else can?

Last week, I sent Tyler Gobble a link to your work and he said it reminded him of Carrie’s. I hadn’t read much of Carrie’s work, but reading it now, I see what he means. I am so seriouseager to hear what you think.

xoCaro

*

July 30, 2013

Dear Caro,

I hope you are having such a wonderful trip with your sister and nephew! Minneapolis has been incredible. We have seen so many friends, and late twenties looks good on everyone. Watching them relax into themselves is making me feel more relaxed too. I now have the urge to kick anxiety once and for all. Getting an MFA in our early twenties was MISLEADING to say the least. The moment I calmed down, I noticed a LOT of people DON’T have an anxiety disorder. I don’t want one either. It is taking up my time. I’ll keep my phobias though. My life is sort of built around avoiding fish and vomit. (Walking around Lake Nokomis, I SAW A DEAD FISH THE SIZE OF MY THIGH).

Anyway, calm is what I want to work out with nods. I read myself into a frenzy, and the frenzy was, I DON’T HAVE A PLAN TO SEE CARRIE YET. One thing I forget about Carrie, and about Nick too, is that they are CALM. I called her, and even her “hello” was grounded. I’m not sure her phone recognized my number. I wonder if folks can read my anxiety-energy from my hello??. It usually either means are you a schemer?? or are you mad at me??. What I’m learning on this trip is that I don’t think people are mad at me. And what I’m trying to say here, is that Carrie is a keel. Before I called her, I chattered my way around the first “scatterstate,” loving it, getting RATTLED by “noiseflowers.” Getting hurt by “i’ll let you know if i hear anything more from you.” I underlined and circled words, sentences… There is an energy here, and there is an energy in Carrie’s calm. I get excitable talking to her, and I don’t get anxious. We made plans to see each other.

When I hung up and hit page two, I wasn’t in racket anymore, I was in flow. If a word or line rattled me, it didn’t jut out anymore, just twinkled around a rock in the river. “And my sunburnt eyes are touching each other with this beautiful delivery of flow hurt…” There is anxiety too: “you have to find a feeling / and hurt its tiny dead / glow with your hurt”. But instead of the anxiety being some illness in Carrie, it is one that she creates and controls. There is energy spinning in her—and it might be just hers, or she might be open enough to deal with my own.

On the phone she and I talked about sharing the sex we write in poems with our parents. I love your thought about the forced merging of concepts (FUELBOOGER) as being like sex and love. I need more people to talk about sex that way. I need more people to talk about sex in every way other than bikini waxes and butt jokes and have you tried….. And so yes, the lights are low in this book, and my eyes never become natural. This groping for vision and relying on sound become mebumbling with someone else’s body in the dark, trying to figure out how it works. I’m thinking about theories of touch and sound. She is building those two experiences without IMAGE. I’m not listening for the pain cattle, I just hear everything. How is this happening?? (NOT a rhetorical question!)

Have your parents read poems you’ve written about sex? (OR WORSE YOUR IN-LAWS?) Wait, do you have poems about sex? Is that what “and spark / and spark” means? (I don’t have your book in front of me—did I quote that right?)

Today is Carrie’s birthday! I’m off to practice my poem for the reading tonight (she is hosting), and to buy her flowers that look like an animal (Nick’s idea).

Love to you guys!

k

P.S. I’m reading with Abraham Smith, and I’m terrified. Not colonoscopy terrified, but on the spectrum.

P.P.S. I want to meet Tyler.

June 13th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Pre-Order HOW TO CATCH A COYOTE by Christy Crutchfield So We Can Talk About It

How to Catch a Coyote

a novel by Christy Crutchfield

Publishing Genius Press

208 pages, paperback, 6 x 8″

ISBN: 978-0-9887503-8-8

July 29, 2014

Within minutes of pre-ordering How To Catch a Coyote by Christy Crutchfield, I was handed an ARC by its publisher, Adam Robinson. I began reading it in a dentist chair (which is definitely a kind of bath, hence the category label on this post) and finished reading it a day later, at the expense of all other work, so absorbed was I in this multivalent narrative of many years in the life of a very difficult family. Sharp cuts in chronology and a kind of chill resistance to poignancy and emotiveness distinguish the novel from the many that expect our empathy or identification as a matter of course instead of asking, as this book does, whether we can possibly empathize or identify with these characters, and what that even means, and whether we even want to.

I was about to get a filling replaced because one fell out and left a hole with a sharp edge that trapped little bits of whatever I was eating no matter how much I tried to chew on the left side only. This turned out to be a great place to start reading How To Catch a Coyote because it is full of teeth and traps.

When I typed multivalent narrative above, which was an edit of the hackneyed layered narrative, what I hoped I meant was from many angles since the book shifts among second and then mostly close third-person POV, but close to all different characters. It turns out I meant nothing of the sort, since multivalent actually means having or susceptible to many applications, interpretations, meanings, or values. This is much more to the point. The POV, the dips and skips of chronology, and other formal devices that you’ll see for yourself are not, IMO, the thing this novel is, though they certainly incandesce around and expertly minister to the thing that this novel is. The thing that this novel is is, is the susceptibility of it, of us, of the characters in the face of not knowing for sure.

No spoilers! I want to wait until you’ve read it to talk about it more. This novel is very very topical, and it will be topical forever or at least as long as there are fathers and daughters, and mothers and daughters, and fathers and sons, and mothers and sons, and–most crucially, I would hazard, but we can talk about it more–brothers and sisters (bcc: Ronan Farrow or does that give too much away?).

Pre-order this book so we can all talk about it a lot. I think it would be a really good book to talk about with college students, and I think it would be a really good book club book, too. Adam and I discovered that we had diverging takes on a single sentence, is how much there is to talk about in this book. I can’t wait until all of you read it!