Easy To Get Here, Hard to Leave

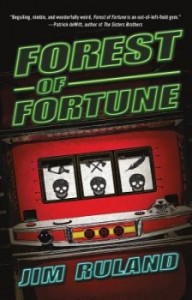

Forest of Fortune

Forest of Fortune

by Jim Ruland

Tyrus Books, July 2014

288 pages / $24.99 Buy from Amazon

In his 1998 documentary Advertising and the End of the World, Sut Jhally defines culture as the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. He further points out that the primary storytellers in our culture—the ones who have the most prominent voice in articulating our value and belief systems—are advertisers. It’s an elegant point, so seemingly simple that its depth can be lost without a few moments to meditate on it.

Most discussions of advertising itself in our culture are limited to the question, “Did that particular advertisement inspire me to purchase that particular commodity?” It’s a feckless question. Jhally notes that the answer to it may be relevant for the people selling the commodity, but it has little relevance to everyone else. Instead, we should be asking ourselves, “What’s the deep-seeded impact of the overwhelming wave of advertising that crashes on us every day?”

What we, as readers and/or writers of novels, don’t discuss much is the relationship of our medium to advertising. Novels are the one contemporary media that is not and can not be saturated with ads. (At least that’s true for the paper ones.) This is one of the reasons I read so many novels. This also leads to one of the great challenges for novelists: to wedge their little story into a culture besieged by several thousand daily advertisements.

Jim Ruland’s recent novel Forest of Fortune is one of those little stories consciously wedging itself into the conversation about advertising. It treads upon similar ground as Jhally’s documentary, yet does so in a tone that allows the reader a bit more freedom in her interpretations. Jhally’s tone is clear from it’s very title: Advertising and the End of the World. Nothing spells doom like that. Ruland also demonstrates his approach early, but in a much more subtle fashion. One of his protagonists, Pemberton, checks into a rundown motel with weekly and monthly rates below the forty-dollar nightly rate. The clerk gives him a sales pitch about one of the rooms. Pemberton is hyper-aware of what’s going on. “A copywriter by trade, [he] knew brochure copy when he heard it, yet was seduced all the same.”

Again, it’s a simple, elegant way of introducing a deep point. Pemberton’s reaction matches a very common one in our culture. We’re often seduced by advertising, untroubled by the knowledge that we’re being lied to, uncritical of the alternate reality it sells. We want the story regardless. In almost every case, it’s the story we purchase. The commodity is just the bi-product, something we’ll keep around until the story loses its luster.

The setting of novel further illustrates this relationship with advertising and consumer commodity culture. It takes place in a fictional California town called Falls City. The name is probably more literary play then heavy handed symbolism. Pemberton arrives there and thinks, “False City, indeed.” It’s a fun way of sending a reader away from the falsity promised by the more specific setting of the novel, Falls City’s Thunderclap Casino.

August 25th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Debora Kuan

PORTRAIT OF MY STALKER

When my stalker stopped stalking me

I died the death of

a million fat blue genies.

That’s how sick in the bream I was.

I wanted to call him Porgy—

because he could follow the scent

of my truffle—

before I knew a porgy is a fish.

The lava lamps slid all the way

into the psychedelic canal.

Fiddlehead ferns wove a shag rug

that couldn’t fly.

I wept hard

in the terminal.

I couldn’t weep.

My god wings

looped in the gold

from a dying head.

For seven years, I didn’t

hear anything

from the state.

And then my certificate

thighs returned

burned.

I tried to soldier on

without. I vacuumed

in the powder

all the way up the snow scraper

and sucked my hair

into a trapezoid.

Running of the things

off a cliff–

Running of my nerves

off my spine–

Porgy, I begged,

I’m a dwarf

planet, I’m a morphed

laminate.

I’m a shut canister

in shut cycle,

spinning out of time.

Bio: Debora Kuan is the author of XING (Saturnalia Books, 2011). She has recently been awarded residencies at Yaddo and Macdowell, and had poems and fiction published in Adult, Brooklyn Rail, Buenos Aires Review, Hyperallergic, The Iowa Review, and elsewhere. She is a director at the College Board and also a senior editor at Brooklyn Arts Press. She lives in Brooklyn.

Working On My Shit: The Art of Distraction

I’m currently working on my novel. I’m also currently working on dying my hair the perfect shade of cornflower blue. I’m also currently working on trying to find just exactly where the hole is in my air mattress as it slowly deflates beneath me.Lately I have found the process of “working” far more interesting than the work itself. According to the ear-worm currently inhabiting my brain–better known as Iggy Azalea– the word I’m looking for is perhaps better known as “the struggle” or “the hustle,” as she so eloquently states in her radio hit “Work.” Put in pretentious art world terms, perhaps I’m also referring to “the process.” But really, I’m talking about the cracks in the sidewalk on the path to the end result. Procrastination. Distraction.

Somewhere between the initial conception of an idea and the completion of the project exists a murky abyss of abstraction in which the horizon line is hidden–or may not even exist. It’s a slice of creation in which anything is possible and everything seems impossible.

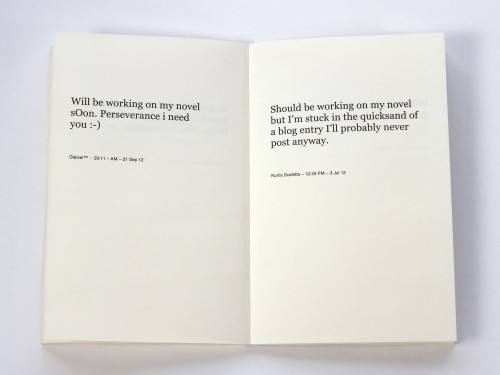

There’s someone else now that seems to share my interest in the spaces in between when a work is imagined and finished: Cory Arcangel. Arcangel has recently published a book titled Working It’s a physical book containing a plethora of tweets written by people working on their own novels. Tweets include “#Offline, working on my novel! =) Be back later!” and “A bottle of red, a hot bath, and working on my novel until my man gets off work. Sounds like a fantastic start to the holiday. :)” The book is bursting at the seams with naiveté, which can be off-putting at times–but behind that naiveté is the glimmers of hope that seem to motivate even the most jaded and misanthropic to write.

Reviewing Working On My Novel for the Paris Review’s blog, Dan Piepenbring has a different take on the book: “a sad monument to distraction.” But what exactly is wrong with distraction? I think perhaps, Working On My Novel, despite being slightly more gimmicky than clever when translated from twitter into a physical book, is an ode to the in between period of creation. It’s about the process of trying. It’s about the process of failing in one direction, yet forging onwards in another. Hash tags and typed smiling faces may be annoying as hell, but Arcangel has a point: Working On My Novel is about “exploring the extremes of making art, from satisfaction and even euphoria to those days or nights when nothing will come, it’s the story of what it means to be a creative person and why we keep on trying.”

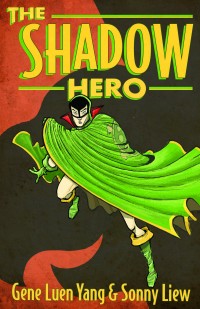

The Shadow Hero

|

The Shadow Hero

by Gene Luen Yang and Sonny Liew

First Second, 2014

176 pages / $17.99 buy from Amazon

Rating: 10.0

|

The Golden Age of comics in the 1940’s was thusly named for the influx in popularity of comics during that time. Publishers operating under a shotgun approach filled the market with every outlandish concept possible, hoping that they’d happen upon the next Superman or Captain America. Comic books have yet to regain that same level of popularity, but for those who frequent comic shops today, they can get a sense of the glut of new comic book characters that flooded the market in the beginning years of comics. The Green Turtle, a shirtless masked man with a cape sporting, well, a turtle shell was one of these transitory characters only lasting five printed issues. As is understandable, The Green Turtle has been forgotten by the mass culture and comic book obsessives alike, so why is he the subject of Gene Luen Yang’s new graphic novel?

Yang has established a strong oeuvre out of deconstructing the super hero mythos while blending it with his Chinese American heritage. His previous works, such as American Born Chinese and Boxers & Saints,combine Chinese mythology with American super hero action. In Boxers, the members of the Boxer Rebellion actually transform into superhuman warriors to defeat European missionaries and soldiers.

With this pedigree it’s no wonder that Yang and artist Sonny Liew found fruitful ground with The Green Turtle. Yang reveals that the hero was created by Chinese immigrant Chu Hing, and that it is conjectured that there was conflict with Hing and his publisher to make the Green Turtle Asian American—the basis of which lies in how Hing never drew The Green Turtle’s face, always obscuring it with a cape or an elbow or depicting him from behind, cape blowing in the wind. Also, Yang is perplexed by the use of racial stereotypes in Chu Hing’s artwork: “the impossibly slanted eyes, the buckteeth, the menacing Fu Manchu grins, the inexplicably pointed ears.” Yang asks whether this “ugly” depiction of The Green Turtle’s Japanese Axis enemies is Hing’s deconstructive commentary or pandering to American publishers, but the truth has been lost to history. As a result, Yang and Sonny Liew endeavored to create a new origin story for The Green Turtle in The Shadow Hero.

And what’s best about the book is that although the book does interrogate American racism—our hero calls the Dick Tracy-inspired Detective Lawful on calling the local crime syndicate “sneaky slant-eyed bastards”—the comic is much more than a simple criticism. What makes the comic a success is that it is a pure superhero origin story on top of being incisive cultural criticism. Yang and Liew follow the tropes of classic comics and create an action-filled book while also managing to make their readers think about race and culture, too. It’s the same genius we’ve seen in Yang’s work before. He uses stereotypes, but also pathos to show readers of all ethnicities what it means to be an outsider and what it means to be a hero.

August 21st, 2014 / 1:33 pm

Paul Cunningham: Why Should I Read YOUR Journal ????

ok, Paul, so why should we read YOUR journal ???

I genuinely enjoy seeing someone’s bogus sense of self-entitlement completely disrupted by the words or opinions of a Deluge contributor. I cannot help that this disrupted person is almost always a white heterosexual male.

I’m obviously not doing any of this for approval from others. I don’t care if anyone disapproves of the kind of writing I’m distributing. I’m doing this to challenge readers. I’m doing this so people who are pissed off about a specific experience or situation have an outlet other than Facebook. I’ve been doing this since 2009 and I plan to continue doing this.

All joking aside, I think everyone should read Deluge because it is a celebration of bodies in the sense that I frequently choose to publish work by writers opposed to phobic violence against all bodies. I am sharing stories of bodies engaged with the resistance of corporate bodies.

And here let me quote myself:

The contents of an issue of Deluge is so many things at once. It might involve a critique of whiteness or the regulations that exist within sociality. It might contain work that is belligerently orgiastic and, at the same time, it might even contain work that is anti- male orgasm. Deluge is a bookshelf on which Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto and Warhol’s Blue Movie transcript both rest. Deluge is when Kim Vodicka writes, “Yes, I am a big ‘ol bitch, and you best / stand behind me. / Feminist is next to godliness.” It is when Roberto Montes writes, “I hear an October voice / Telling me to fuck / Is this racist / The white boys ask / When they grab my butt / Really wondering / How anyone could be different / Or turned like a gasket out.” When Monica McClure writes, “But all I really want / is to live a good life / paid for by someone who feels / illiterate in symbolic systems of manhood / For him I will fill a bathtub / with expensive rosewater / that I got for free in swag bags / I’ll stuff holes with pure sugar cane / bought with the IMF budget of countries / who failed to understand the compromising / nature of relationships.” It is when you and Gary write lines like, “the wilderness knows i am a real fucking pig, and apples my mouth, over and over / i let myself get frosted by all the men dressed as trees.”

Shit happens. Poetry happens. “Same shit, different bidet,” READ MORE >

Crystal Eaters

|

Crystal Eaters

by Shane Jones

Two Dollar Radio, 2014

172 pages / $16.00 buy from Two Dollar Radio or Amazon

Rating: 10.0

|

So my dad’s an alcoholic. (That’s really hard to admit. In fact, this is the first time I’ve typed it out, as I’m drafting.) He’s not a monster. He never beat me or did any physical harm to me. Just had outbursts and left me with daddy issues.

So the reason why I’m sharing this is because Shane Jones’s Crystal Eaters helped me come to terms with some of my childhood. If you haven’t heard the premise of the novel here’s the rub: people in this village have a crystal count. Crystals are depleted when people get hurt, age, etc. When you reach zero you’re dead. There’s a rumor that eating rare, black crystals will increase your life count, but it’s just a rumor. Black crystals do work like psychedelic drugs though. Basically, The Crystal Eaters is a novel of addiction. Everyone is addicted to something, whether it’s their self-image as a good parent, the idea of extending their life, or they’re addicted to imbibing the psychotropic black crystals, themselves.

So the son, Pants, of the main family in the novel feels guilty because his mom is dying and he can’t really do much about it because he’s in jail for tripping balls on black crystal in public. In prison, Pants realizes that he’s an addict because his parents beat him instead of not taking the time out to understand him. That means a fuckton to me because I’m an addict, too—only to porn and alcohol. What I’ve come to realize, and what Jones reinforces in his novel, is that my dad’s fucked-upness is not my fault. It’s just how his parents equipped him. “Her father had done the same to her, and so did Dad’s, and it worked, look at them, adjusted people. She didn’t necessarily believe what she thought, but her family history was stronger than her head.” As a result, the same becomes true for Pants. And even though he feels super guilty and blames himself for his mother and dad and little sister’s misfortunes, it’s not actually his fault.

“The universe is a system where children watch their parents die,” which I take to mean, the world just spins, the city grows, the sun gets hotter. Of course there’s the chance that we’ll become addicted, too: it’s a way for our bodies to heal—a coping mechanism. We just need to examine the source of our desires. Why do I need to write? Why do I need to live forever? Why do I need to drink until my brain shuts off? If we can get a grasp as to what our motivations are, maybe we can have an easier time through life. The best we can do is not to fixate on the counting down to zero—because we will all reach zero—and, if we’re lucky, touch a heart or two on the way. Read the novel. Maybe it will help you come to an important realization, too.

August 19th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

5 Points: “Strange Tarot” by Jamalieh Haley

1) Reading and experiencing “Strange Tarot” is like spying on a tenuous and tense relationship in which one part of a self guides and chides the other. At some points, even, it feels like it incarnates you. (Most Tarot Poetry’s an exhausting exercise in ekphrasis. Yawn. That, or the Tarot Poems range so far afield that there’s nothing Tarot about them. Jamalieh Haley’s “Strange Tarot” is still very much Tarot—superficially, in titles, imagery and in the way the poems on the page are shaped like Tarot cards—but indeed a strange, strange Tarot, benefiting and enhanced greatly from psychedelic imagery that only issues from a highly pressurized and agitated mental state.)

“Arrive inside your silhouette. Open the china. Do anything there.”

2) The critical element of Tarot is the relationship between the fortune teller and the supplicant. And, for me, in Strange Tarot the self is telling itself its own fortune. The self betrothed to itself. And this “conversation” (or fortune telling) within the self, which we are privileged to enjoy and shudder at, is rife with flaring tensions and instability, extrusions of cruelty and violence verging constantly towards, like suicide, a kind of desperate, ritualized and salvational make-up sex. Yes, the fire of consummation is what will save and consume.

And let me say again how lucky we are to be overhearing and looking in on this lover’s quarrel of the soul (and itself).

“throw down salvation to the beast you demand.”

“. . .cut up your head into a paper mask and transform everything into the sun.”

3) The voice of these poems is high-strung, edgy, often cruel and sadistic, but READ MORE >

August 19th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Imaginary Portraits by Joshua Ware

Imaginary Portraits

Imaginary Portraits

by Joshua Ware

Greying Ghost, 2013

Limited Edition / Chapbook Page

My thumb surfs Instagram. I sit at my desk to write this. I am constantly distracted by a false reality. There are people I know there. They are eating tacos, taking pictures of sunsets, their partner stares out from a small screen I hold in my palm, I press like to let them know I see them. There is no way to escape our new duality, but I think it helps to be aware of this reality. Here is the problem: what is real or more real. How do we classify reality & does this change through location, movement, isolation. Joshua Ware introduces me to a world I know well. Here it is winter. I am wearing a hat. I am looking at myself as reflection. I am not sure it is really me.

A small blue book / It fits well in my hands. Small poems / Coy, they coax & murmur / I know you / the shape of darkness

You are dressed for winter, a chill in the air. Waiting. What forms do we take when met with a lens? How do we become a recreation/abstraction? How are we changed?

You sit atop a gray river / side rock, as water rush / swallows your voice, drowning you / by volume. The poet relocates to a new city. A traveling between two regions. Wind gusts through our private stillness. We are always somewhere. There is a struggle in always knowing where you are. Is it supposed to make you different? Should we expect change? Your muted / mouth opens a space for / poetry

Hello, avoidance. The escape plan proposal is returned, rejected. I sit at my desk with coffee. It is cold now. I feel this speaking to some part of me. No matter how surrounded I am there is loneliness in my body.

IMAGINARY PORTRAIT

In an otherwise darkened room

computer-light illuminates the contours of

your face, mimicking the neon shine of

an interstate motel sign that burns

through cornfield and prairie grass

somewhere in Middle America, as you drift

into a reverie of body parts, hoping to avoid looking at

yourself while you look at yourself

in a mirror. But your reflection

returns to you always in words

and the charred remains of cornstalks.

August 18th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Jos Charles

Jos Charles is a southern california writer and founding-editor at THEM – a trans literary journal. They have poetry published (and/or have publications forthcoming) with BLOOM, Denver Quarterly, HTMLGIANT, Metazen, Radioactive Moat, boosthouse’s THE YOLO PAGES, as well as variously online. Their writing has also been featured on Huffington Post, BitchMedia, Entropy, Medium, The Fanzine, The Quietus, interviews with GLAAD, LAMBDA Literary, Original Plumbing, and other pieces forthcoming.

Justin Marks: Why Should I Read YOUR Book ????

ok, Justin, so why should we read YOUR book ???

Why should you read my book? I have no fucking clue. I don’t even know why I wrote it, except that doing so was part of a compulsion I have to make things, and the only means I have for doing that, the “talent” I have, is writing. Writing in general, poetry in particular. If it were different, I would have written a novel or a memoir or a scholarly book or something YA.

My book is none of those things. There is some narrative, but it’s pretty fractured, as they say. There are characters, but not the kind you really get to know. I present them from my point of view only. It’s poetry, for Chrissakes! The lyric “I.”

The book is about me and my life, but also other lives I wish I’d had. Or think I wish I had. It is about struggle, though is decidedly not “My Struggle.”

Overall, it’s pretty adult. By which I don’t mean porn, though there is a fair amount of sex (not) happening in the book. It’s about trying to be a grown up and how much that fucking sucks. It’s about choosing a life and then having to actually live it (auto correct tried to change “live” to “love”). It’s about making decisions and having to live with them, which also fucking sucks.

amount of sex (not) happening in the book. It’s about trying to be a grown up and how much that fucking sucks. It’s about choosing a life and then having to actually live it (auto correct tried to change “live” to “love”). It’s about making decisions and having to live with them, which also fucking sucks.

It’s about broken bones. And booze.

Life, death, love and (un)happiness. Kids.

And then, by the end, it’s about realizing what a sick piece of shit you are and having to live with that. Having to figure out a way to be a better person, behave responsibly because, really, the way things are going, it’s just not going to end well.

Or maybe it’s not. Maybe it’s about something else entirely. I don’t know. You tell me. (Justin Marks, 8/2014, NYC)