art should be nice, polite– and help you across the street ………………………………………………………. #arpoetica

at school people say things

at school people say things

i can feel myself turn inward

the escalation from ‘politely responding with terse expressions of acknowledgment’

to

‘feeling my face morph into something soft and wet while seconds turn to minutes turn to hours

turn to years and i am staring and nodding and smiling strangely and maybe saying “yeah” or

“uh huh” while internally moving at a speed of one hundred miles per hour and experiencing

feelings in a linear manner that go from anxiety to self-hatred to self- aware self-hatred to

sarcastic self-aware self-hatred to “what is going on” to “what…” to thoughts about myself in

terms of the current social situation to thoughts about myself in terms of some insanely large

context like forever to thoughts about myself in terms of myself to extreme feelings of

detachment to nothing while having already started to feel even more anxiety about the prospect

of tweeting said feeling, which is really many feelings, a poly-feeling, which may or may not be

explicable in 140 characters or less in a manner that is clear, enjoyable, and relatable’

happens quickly

my face feels numb and my mouth, i think, is open

someone smiles at me

i fall further into myself, screaming

from If I Really Wanted to Feel Happy I’d Feel Happy Already

I think

I am

averse

to long

left-aligned

and

narrow

poems written

like this

I think

because I

think line

breaks mean

something

and I

don’t see

much meaning

in these

I think

I am

averse to

publishing

long

left-aligned

and narrow

poems

arranged

like this

in

print

because it

seems

like a

waste

of

paper

and if

you submit

one to

me, like

the ice bucket

challenge

made me think

‘oh no, the

environment,

the drought,

the waste,’

then I

will probably

try to

edit

your

long

left-aligned

and narrow

line break

riddled

poem

into some

prose.

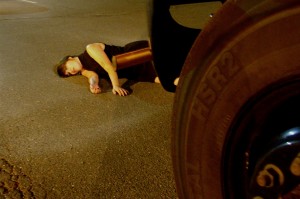

BEAUTY BY HTMLGIANT — WOMEN POSING AS DEAD ANIMALS

Tara Boswell, dead deer.

October 3rd, 2014 / 11:29 am

His Geography: The Collected Works of Michael Ondaatje

A. “There are stories the man recites quietly into the room which slip from level to level like a hawk.”

The English Patient

1. A popular mistake about Canada is that it is fundamentally North. Otto Friedrich’s biography of Glenn Gould compares Canada’s relationship to the North with America’s to the West, except there’s no Disneyland in the Arctic. Most of Canada’s population is concentrated in the southernmost quarters; post-Gould Toronto produced Petra Collins’ Instagram, among a lot of other non-Drizzy things. One quarter of all postwar immigrants to Canada came to Toronto. Canada’s history is only one centennial in; its youth relative to the rest of the world may account for why the rest of the world sometimes acts so strange about it. Cats still aren’t sure about humans because in evolutionary terms they haven’t been around as long as dogs and are still socializing themselves. There are no cats in the Bible, for instance.

2. The book of 2014, nonfic anyway, was Capital in the 21st Century by Thomas Piketty, a book carrying the mythical glow of pregnancy. Stephen Marche reviewed it for the Los Angeles Review of Books, calling it ‘perhaps the only major work of economics that could reasonably be mistaken for a work of literary criticism.’ He relates realism’s utter defeat of the other forms, the fun ones like lyricism or even minimalism, and credits Jonathan Franzen, that old serpent, with its proliferation. We already knew all that. One of the writers Marche suggests has fallen out of usage is the Canadian Michael Ondaatje: from Ontario by way of Sri Lanka, educated in England, known for hushed, haunted pieces like The English Patient (1992), Divisadero (2007) and The Collected Works Of Billy The Kid (1970). He also wrote a memoir, Running In The Family (1979), which includes the following clip:

“At St. Thomas’ College Boy School I had written ‘lines’ as punishment. A hundred and fifty times. [fragment in Sinhalese] I must not throw coconuts off the roof of Cobblestone House. [fragment in Sinhalese] We must not urinate again on Father Barnabus’ tires. A communal protest this time, the first of my socialist tendencies. The idiot phrases moved east across the page as if searching for longitude and story, some meaning or grace that would occur blazing after so much writing. For years I thought literature was punishment, simply a parade ground. The only freedom writing brought was as the author of rude expressions on walls and desks.”

3. Ondaatje’s family is Dutch-Ceylonese and was well-off. By various vagaries his father ended up a chicken farmer, his mother on staff at a hotel, and he and his siblings diffused thru England, America, and Canada. Much of his writing is liminal: the act of falling on a map, and why is it called falling? ‘We are the real countries’, vows a character in The English Patient. Disdain for colonialism and its legacies is a chief Ondaatje engine; another character in The English Patient insists that everyone white is motivationally English: ‘when you are bombing brown races you are an Englishman’. That character’s name is Kim and he’s Sikh, which we know because he wears a turban. Almasy, the sophisticated count burned into patienthood if not Englishness, is Hungarian but nomadic. He hates ownership, being owned—and the idea that when there’s a war on, where you’re from becomes important.

Ondaatje produces fantasias of language, requiring much suspension of disbelief, risking collapse if pulled too far out of context. As stated by Pico Eyer in an essay for the New York Review of Books called ‘A New Kind of Mongrel Fiction’: ‘ there will always be some for whom Ondaatje is too rarefied or exquisite.’ Lines like ‘giraffes of fame’ and little leashes of them like ‘later my hands cracked in love juice/fingers paralyzed by it arthritic/these beautiful fingers I couldnt [sic] move/faster than a crippled witch now’ qualify as sentimental dithering to the worst agnostics. Glenn Gould said he believed in God as long as it was Bach’s; I believe in a groundless, fermented prose style as long as it is Ondaatje’s. Even when it’s a little bit bad, it is never not beautiful.

‘There is nothing wise about a harbor, but it is real life. It is as sincere as a Singapore cassette. Infinite waters cohabit with flotsam on this side of the breakwater and the luxury liners and Maldive fishing vessels steam out to erase calm sea. Who was I saying goodbye to?’

Ondaatje, Running In The Family

October 3rd, 2014 / 10:00 am

Htmlgiant’s Last Day is October 24th

Today is a few days after our sixth anniversary. Blake Butler and I started this place because we wanted a hub for all of the writing we love, all of the people we enjoy reading, and to do it with a certain openness that we both appreciate. Along with everyone else that came along with us, we succeeded (and occasionally failed) at that for many years.

October 24th, 2014 will be the last day of operation for Htmlgiant. I’m going to step aside as managing editor effective immediately, and in the next few days I’ll open posting up for nearly everyone that has ever been a part of this site. On October 24th I will disable posting privileges for everyone and leave the site up for as long as we can afford it.

The next few weeks will hopefully be interesting, because if there’s anything this website deserves it’s an uncontrolled flameout.

The amount of respect and admiration I have for so many of the writers and editors that we’ve worked with over the years cannot be overstated. There are so many special people I want to hug and thank, and I have a feeling I’ll be doing it in person for years to come.

See you soon.

25 Points: Matt Meets Vik

|

Matt Meets Vik

by Timothy Willis Sanders

Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2014

164 pages / $13.95 buy from Amazon

|

Or ‘Rich Meets Vik’ to review ‘Matt Meets Vik’ as Richard Brammer teams up with his girlfriend ‘Vik’ (Victoria Brown) to review this book.

1. Vik: At the end of the book, I didn’t expect it to be the end and kept turning (scrolling) the pages thinking there would be another chapter. When I realised that it was the end I was pleased at the way it ended.

2. Vik: I’m a woman so I don’t often get to hear a man’s raw thoughts. I liked that this book put me in the position to see male thoughts. I assume that they are real-ish male thoughts.

3. Rich: Shit! I haven’t started reading the book yet. I’m going to read it and find out. I’m not sure but I think I have real-ish male thoughts to compare them to, as a scientific control.

4. Vik: The book is set when Snake was a big deal on Nokia phones. I never had a Nokia, but I remember the enthusiasm Nokia owners had for Snake.

5. Rich: I had one of those Nokia’s. Before that I had a Nokia 5410 or something (in about ’95 and this was before my impoverished dispersed family had a house phone even). I loved Snake though. I was as addicted to Snake as I could’ve been to anything 2-dimensional at that time. I used to commentate to myself about my own performance on Snake like it was a sport and I was a great renowned competitor.

6. Vik: Actually I did have a Nokia phone but it was such an early Nokia that it didn’t allow you to access your address book when typing a text message so you would have to memorise the phone number of the person you wanted to text when texting. Which was terrible.

7. Rich: Shit! There’d be v apathetic riots if technology was designed like that now. My first phone had a text facility but the network ‘didn’t support it’. Should we review this book now?

8. Vik: I read this book in about 4 sittings; it is 177 pages long. I read it really quickly.

9. Vik: I’m a woman named Vik but I didn’t identify that much with the character named Vik, in fact I identified as much with the character named Matt as I did with Vik.

10. Vik: There are other characters, Chantelle, Ralph, Lucas and Esme and maybe some more.

October 2nd, 2014 / 12:00 pm