Lily Hoang

https://literature.ucsd.edu/people/faculty/lhoang.html

Lily Hoang has published some books and won some awards. She is Director of the MFA in Writing at UC San Diego.

https://literature.ucsd.edu/people/faculty/lhoang.html

Lily Hoang has published some books and won some awards. She is Director of the MFA in Writing at UC San Diego.

Up at the Boston Review blog, Carmen Gimenez Smith gives real talk about being a poet-academic and the inherent privilege of it:

I often struggle with how I might best use the privilege I possess as a middle-class poet. I’m afforded the platforms of professor and writer, platforms I don’t really utilize to effect change in the world. This might be due to a cultural indoctrination suggesting that poetry is a marginal practice, yet poets such as Adrienne Rich, Denise Levertov, Gary Snyder, Brenda Hillman, and, more recently, Mark Nowak, Shane McCrae, Jena Osman, and Craig Santos Perez have utilized their privilege and platform to uncover, expose, and counter accepted narratives about living in a declining empire in which our agency as citizens is shrinking. While the government watches us, more and more poets and writers are watching back, documenting the injustices that stain our present moment. We need more of that. I should be doing that.

I’m currently editing this massive anthology with Joshua Marie Wilkinson called The Force of What’s Possible: Writers on the Avant-Garde and Accessibility (heading to an Internet purchasing place near you in 2015 from Nightboat Books). In it, we have roughly 100 original essays discussing the role of accessibility in writing as well as Badiou’s questioning of Empire and recognition. Putting together these essays, especially in light of Carmen’s BR post, I keep returning to a word: responsibility. What responsibility do we have as writers? Do we have a responsibility? To whom? Should we even care about accountability? And accountable to whom? We have this great power: the ability to tell stories. What do we do with it? Do we just recycle the same and call it new?

We get a ton of books for review consideration on my desk for The Volta. Even though we tried to run weekly reviews for a year, that still didn’t seem to touch anything but the best stuff off the top. So, I’ve pulled out a dozen or so that I’m really excited to read this summer:

Rae Armantrout’s Just Saying is the follow-up to the follow-up to Armantrout’s Pulitzer Prize winner, so I won’t be surprised if it gets less attention than Versed or Money Shot—though it shouldn’t. I’m halfway through it, and it’s just as good:

A woman writes to ask

how far along I am

with my apocalypse

What will you give me

if I tell?

Say you’re giving a reading, what’s the perfect question? What question do you loathe?

Say you’re in the audience, what question do you wish someone else would ask? What question makes you feel embarrassed that someone actually asked it?

Got some dollar dollar bills? Support six kicking poets kick it through the US.

The Line Assembly Poetry Tour and Documentary might even be coming to a city near you.

I love them. You should too.

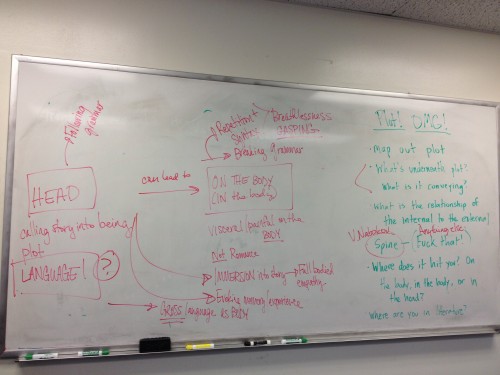

This is what happened in my grad Form & Technique in Fiction class today:

Here is how it happened. Every Wednesday, students read articles and essays that are NOT fiction. Last class, they read & we discussed a unit I called “The Human Body,” which included the following texts: Dong et al, “Unilateral Deep Brain Stimulation of the Right Globus Pallidus Internus in Patients with Tourette’s Syndrome”

(from The Journal of International Medicine); Grahek, Feeling Pain and Being in Pain, “Ch. 1: The Biological Function & Importance of Pain”; Ramachandran, Tell-Tale Brain, “Ch. 3: Loud Colors and Hot Babes: Synesthesia”; and

Scarry, The Body in Pain, “Ch.3: Pain and Imagining.”

Here is how it happened. Every Wednesday, students read articles and essays that are NOT fiction. Last class, they read & we discussed a unit I called “The Human Body,” which included the following texts: Dong et al, “Unilateral Deep Brain Stimulation of the Right Globus Pallidus Internus in Patients with Tourette’s Syndrome”

(from The Journal of International Medicine); Grahek, Feeling Pain and Being in Pain, “Ch. 1: The Biological Function & Importance of Pain”; Ramachandran, Tell-Tale Brain, “Ch. 3: Loud Colors and Hot Babes: Synesthesia”; and

Scarry, The Body in Pain, “Ch.3: Pain and Imagining.”

I developed this class. Now, I am teaching it.

ENGL 534: Form & Technique in Fiction

Reading Outside of Fiction

COURSE DESCRIPTION

As writers, it’s important that we gather inspiration from a broad array of sources. Often, between coursework and personal interest, it’s impossible for us to read as widely or diversely as we could, and it’s often outside of the discipline of creative writing and literature that we gain the most inspiration. In this course, we will read from a variety of disciplines and use the knowledge to generate prose. The texts you will encounter in this course may be difficult. It isn’t important to understand every word. It is even less important that you “like” it. What matters is that you use it to generate new material.