Writing Against the Censor

Before Covid arrived and ruined everything, I was emailing with a writer I look up to, asking him about—I guess you would call it—procrastination. This was maybe January. I’d developed a bad habit of spending my Sundays chained to the computer, worrying over writing, sometimes trying to get blood from a stone, feeling like I wasn’t productive if I ripped myself away and did things. It was a bad state of mind and a worse state of creation—even worse when you think about what was coming. The writer I was talking to said:

I’d say–when you’re ready, write with fury and keep going–when you get tired, go out, take a walk, don’t think about the story; then when you’re ready, go back in and keep going. The writing mode is the opposite of the writing mode; the writing mode is a dream mode, similar to a daydream mode, or even more, a reading mode.

I’ve let that guide me these last sixish months of trying to write—despite knowing that the world as it was before March might never return—writing which sometimes resembles simply freaking out at the difficulty of writing, let alone finishing anything, and which at such times results in my simply migrating to social media and engaging in the supreme ease of participating in the cycle of rage and anxious irony that defines it, in particular making mountaintop-sounding proclamations about politics in long, bitter posts on Facebook (a favorite hobby of mine). In those moments writing fiction feels singularly useless. There is a world of active, fast conflict happening online. But the page is slow and no one likes it until it’s done, and probably not even then.

I think that hesitation before the page comes, like most mental paralysis, from fear. Will I be able to do it today? Am I a fake? Am I writing the wrong thing? In therapy sessions, I call it a “censor.” I might write a sentence, or a paragraph, and it’ll turn out less than good. So better to write nothing at all. Nothing lost, nothing attempted—but everything lost, because that fear you (I) felt at the computer screen echoes through the day and into the night and invades my dreams—the dream mode is no more a dream mode. Once it takes hold, I find, the censor censors everything.

But then there are mornings when the censor shuts off, or it’s like it wasn’t ever there, or maybe like it’s revealed to have been something that was somehow only ever the product of my own will, my own decision making. There’s no incessant “no”—no groans of, “You can’t do that because you might fail”—only daydreaming at the keyboard, playing a bit, kicking around images and sounds and half-remembered imprints of, for instance, a gas station in Tampa from twelve years ago. Then everything opens up and ambition and ego go mostly quiet—you can still hear them but they’re whimpering somewhere in the background, and it’s all about the expansion and contraction of an invented voice through the always-weird medium of words. Writing, in other words. The other mode—the censored mode, driven by fear—I don’t think I’d call that writing. It’s typing. It also might be a necessary part of the process, those many nothing attempts.

Anyway, welcome back, HTMLGiant.

Setting A Scene In A Bar

Alaska Bar during the week it closed. Photo by Erik.

New York City, NY (resident 2010-present)

Ontario Bar

This is a classic dive with a suspicious Canadian theme. It sits across from a very fine Indian restaurant (fare of the northwestern subcontinent) on a long stretch of Grand Street in East Williamsburg, with many other bars–dives and otherwise. My normal procedure here is to drink a lot of whiskey sodas and say some friendly things to whomever is around. When I first moved to New York my colleague Bobo encouraged me to go to Ontario Bar, I think because it had more of a cozy neighborhood vibe (at the time) than places nearer to Bedford Avenue. He could sense that I missed smaller-city dives? In addition to serving other bartenders, staff are known to be friendly to dull-eyed, lonely men who work in production and creative services. It’s not a bad business model in Williamsburg. I once heard a bartender complain that she only makes money between the hours of three and four. Close later and change the whole experience of the night. READ MORE >

Twenty-Eight Things I Wrote in the Margins of Brian Blanchfield’s PROXIES

1. a trying-out … placing a variety of pressures on each essay’s titular subject, seeing what happens, where it leads … form is determined by the action of a restless mind

2. like Barthes, exploring middle ground between autobiography and criticism, imbuing collective experience of culture with intimacy, vulnerability, even if merely by virtue of subject selection … critical unpacking of shared/common behavior … housesitting becomes occasion for reflection on “commensalism” and the “citational,” etc.

3. certain propriety about syntax, tone … implied author and the “man of letters”

4. closed-book constraint is refreshing in part because there’s not that excessive referentiality that’s become so common among lyric essays

READ MORE >

Exhaustion

I’m very happy with my decision to maintain that silence even while working in the publishing industry. I know a lot of people say that networking is as important for writers as it is for anyone else, but I think that’s crap. Writing should stand on its own. Period. I’d hate for friendship to muddy the waters of a publisher’s decision to take on my work, even if — especially if — that muddying effect were to work in my favour.”

—Jason Hrivnak in conversation with Beth Follett, 2009

Hrivnak has written a single book, The Plight House, which came out in 2009. It’s one of my favorites. There is hardly any presence of him on the internet. The quote above pushes an idea that I think is true, and wish that everyone could realize it. It’s taken me five years, and sometimes I still doubt its veracity.

Ideally, I’d like to be invisible to my imagined audience. Yes, we live in a world where it’s important for the writer to take part in the publicity effort, but I think that The Plight House (and other books like it) work best when the author remains somewhat faceless. In terms of the work itself, I’m reasonably satisfied by the extent to which my desire to disappear has soaked down into the deepest levels of the book. Yes, much of the story is very personal, but that material is so intermixed with pure invention that even readers who know me well won’t be able to “find” me there. I’m not invisible, but I’m next-best-thing-to-invisible.

What makes boring poetry boring?

I posted this question on facebook: ‘What makes boring poetry boring?’

People responded with a variety of reasons: no imagination, using tired techniques, failure to innovate, failure to obscure, the smack of phoniness, being too safe, being edgy for the sake of being edgy, cliches, the culture of commodification, not making an emotional connection. All of these make sense. All of these are different.

Working On My Shit: The Art of Distraction

I’m currently working on my novel. I’m also currently working on dying my hair the perfect shade of cornflower blue. I’m also currently working on trying to find just exactly where the hole is in my air mattress as it slowly deflates beneath me.Lately I have found the process of “working” far more interesting than the work itself. According to the ear-worm currently inhabiting my brain–better known as Iggy Azalea– the word I’m looking for is perhaps better known as “the struggle” or “the hustle,” as she so eloquently states in her radio hit “Work.” Put in pretentious art world terms, perhaps I’m also referring to “the process.” But really, I’m talking about the cracks in the sidewalk on the path to the end result. Procrastination. Distraction.

Somewhere between the initial conception of an idea and the completion of the project exists a murky abyss of abstraction in which the horizon line is hidden–or may not even exist. It’s a slice of creation in which anything is possible and everything seems impossible.

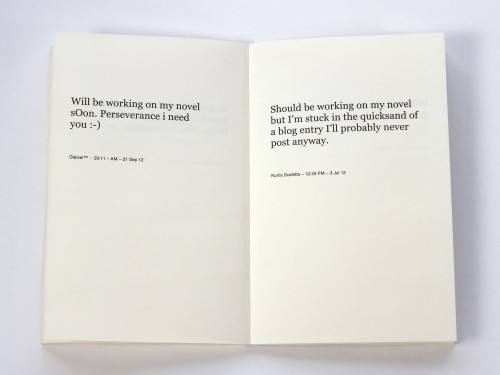

There’s someone else now that seems to share my interest in the spaces in between when a work is imagined and finished: Cory Arcangel. Arcangel has recently published a book titled Working It’s a physical book containing a plethora of tweets written by people working on their own novels. Tweets include “#Offline, working on my novel! =) Be back later!” and “A bottle of red, a hot bath, and working on my novel until my man gets off work. Sounds like a fantastic start to the holiday. :)” The book is bursting at the seams with naiveté, which can be off-putting at times–but behind that naiveté is the glimmers of hope that seem to motivate even the most jaded and misanthropic to write.

Reviewing Working On My Novel for the Paris Review’s blog, Dan Piepenbring has a different take on the book: “a sad monument to distraction.” But what exactly is wrong with distraction? I think perhaps, Working On My Novel, despite being slightly more gimmicky than clever when translated from twitter into a physical book, is an ode to the in between period of creation. It’s about the process of trying. It’s about the process of failing in one direction, yet forging onwards in another. Hash tags and typed smiling faces may be annoying as hell, but Arcangel has a point: Working On My Novel is about “exploring the extremes of making art, from satisfaction and even euphoria to those days or nights when nothing will come, it’s the story of what it means to be a creative person and why we keep on trying.”

A Corporate Theory of Literature

The following writing was rejected, in June 2014, from an internal essay competition held by the company I work for. The prompt was: is a well rounded education valuable? Discuss. The company I work for is a large conglomerate that owns brand consulting shops, media buying groups, and advertising agencies. The essay is based on a manifesto I wrote in 2011, which appeared on the artist Tom Moody’s blog, and based in-part on the views of middle class creative theorist Slash Lovering.

Writing in Plain Sight: The Author, the Narrator and the Difference (if any)

When fiction reading is going well for me, I translate the words into something that’s both fiction and non-. Take the novel The Name of the World by Denis Johnson, which I read recently for the first time. Here’s the first paragraph:

Since my early teens I’ve associated everything to do with college, the “academic life,” with certain images borne toward me, I suppose, from the TV screen, in particular from the films of the 1930s they used to broadcast relentlessly when I was a boy, and especially from a single scene: Fresh-faced young people come in from an autumn night to stand around the fireplace in the home of a beloved professor. I smell the bonfire smoke in their clothes and the professor’s aromatic pipe tobacco, and I feel the general unquestioned sweetness of youth, of autumn, of college—the sweetness of life. Not that I was ever in love with this scene, or even particularly drawn to it. It’s just that I concluded it existed somewhere. My own undergraduate career stretched over six or seven years, interrupted by bouts of work and transfers to a second and then a third institution, and I remember it all as a succession of requirements and endorsements. I didn’t attend the football games. I don’t remember coming across any bonfires. By several of my teachers I was impressed, even awed, and their influence shaped me as much as anything else along the way, but I never had a look inside any of their homes. All this by way of saying it came as a surprise, the gratitude with which I accepted an invitation to teach at a university.

I relate strongly to the narrator, who we learn later is named Michael Reed. The amount of emotional overlap between Michael’s and my life is scary. I too held similar images of academic life, for me perhaps set in the fifties and involving more letterman sweaters, but the same otherwise. Like the narrator, it took me six or seven years to finish college, and involved three transfers. I was also impressed by my teachers, and I also never imagined seeing the insides of their homes. This is exactly what I look for in a novel reading experience, a character who’s as much like me as possible, and telling his—our—story with a compelling, authoritative voice. Telling me, in short, about me.

But at least as important as my strong relationship to the narrator is the strong relationship I feel to the author. I read the above sentences, and I feel like I know the narrator’s shadow figure, Denis Johnson, very well. How can one write of this bucolic college tableau, “Not that I was ever in love with this scene, or even particularly drawn to it,” and not on some level feel the same way? I think of actors, who have to find something relatable in every character they play, even reprehensible ones. Can a writer fake this stuff? If he can’t, then what’s really the difference between Michael Reed and Denis Johnson?

And still there’s a third level in which I feel a deep connection to this work. As a writer myself, I feel a strong professional connection to the author for these perceived overlaps in our histories and psyches. Denis Johnson is a successful—even world-class—writer, and I hope that these emotional/biographical similarities mean that I somehow—despite all evidence to the contrary—am on some kind of path to a literary career. This guy is just like me, and he won the National Book Award! I can’t help but hope, despite my age, lack of comparable publishing success and absence of completed work as riveting as, say, Jesus’ Son, that I am somehow in the same game as Denis Johnson.

So The Name of the World hit me squarely because I relate to the narrator, and the writer, and because I want to succeed like the writer has succeeded. In other words, I’m about as perfect an audience for this novel as there is.

In all my exploration of writers and writing (B.A. in English, M.F.A. in Writing, 25 years of near constant reading and writing outside of class), I’ve rarely heard anyone mention this third, professional angle to readerly empathy. I suspect this is because, back when I was in school, writers still entertained the idea that most of their audience would come from actual readers and not other writers. There were of course “writers’ writers” back then, or those authors who were read almost exclusively by other writers—David Foster Wallace comes to mind. But I still think we were largely in the Saturday Evening Post romance of the reader/writer relationship, that is, educated people sitting down with books and magazines and being sucked in by written pieces. The author Gary Shteyngart gets credited for having said, “The number of people who read serious literature is now exactly equal to the number of people who write it.” Maybe an exaggeration, but probably the healthiest angle from which to come at a literary writing career in 2014.

Despite my deep interest in the writer of The Name of the World, I wouldn’t like the book as much if it were memoir. Imagine if the first sentence of the intro paragraph were “Hi, I’m Denis Johnson,” and “Denis Johnson” replaced “Michael Reed” throughout. I would still be interested in the book, and I’d probably read it and relate to it deeply at points. But I could never fully imagine myself into the narrator’s plight the way I can with the novel The Name of the World. In other words, the memoir The Name of the World would never quite be about me and Denis Johnson the way the novel is. The fiction tag allows Johnson, or any writer, to play both hands: he can utilize a fictional narrator, which allows the reader more leeway to see herself in the character, and he can titillate with suggestions of autobiography, which allows the reader to form empathy with the writer. Somehow these two readerly perspectives aren’t contradictory. The narrator of The Name of the World is both Michael Reed and Denis Johnson, and I’m fine with that.

May 12th, 2014 / 10:00 am

25 Pieces Of Writing Advice To End All Writing Advice

Most writing advice comes off as watered down and lacking both bark and bite. I’m not sure exactly why, but I think it has something to do with the writer being hesitant to have his or her name attached to something potentially offensive. Very few seem to crave the public attention of being a curmudgeon spitting on the idealistic novice.

I’ve spent the last month contacting authors (both major house and indie; critically acclaimed and up-and-coming; big names and small; cock wavers and VIDA junkies) and a few influential editors, asking each to submit their most heartfelt, brutal, and honest writing advice they could think of. I promised to publish what they wrote anonymously. The following are the results.

Sifl and Olly on poetry

(The poetry starts around 1:23. Make sure you stick around for S&O’s “Beat Poets” song.)