ENFANT TERRIBLE GONE BAD: AN INTERVIEW WITH PRETEEN GALLERY’S GERARDO CONTRERAS

“[Our community is] one that constantly sabotages itself: the anticommunity of networked souls.” —John Kelsey, Next Level Spleen

There is no sentiment more omnipresent in the art world than that of dissatisfied skepticism. Today more than ever individuals exposed to the arts derive conclusions about the value of the work based on the context or network in which the art is presented.

The link provided on Preteen’s Twitter page describes Preteen Gallery as “a small contemporary art space in Mexico City.” In true “networked soul” fashion, I emailed Preteen, stating: “I would like to interview you: either ‘you,’ the actual person behind the feed, or ‘you’ as an online performer/entity.”

Gerardo Contreras, founder and director of Preteen, grew up in Ciudad Obregón and moved to Hermosillo to study architecture in his twenties. He founded Preteen in 2008 by transforming an unoccupied apartment space in Hermosillo he had under his possession. The name stems from its founder’s early memories of watching online pornography, in a time when there were no real restrictions on Internet content. In regards to his curatorial ideology, he cites Javier Peres’ Peres Projects and Maurizio Cattelan’s The Wrong Gallery as influences.

The workload Contreras has undertaken is certainly prohibitive of the severe drug habits his tweets imply. In a single month his schedule included opening Jaime Martinez’s Shyness is Nice Don’t Ask Me, curating I’m Too High to Deal with this Shit Right Now in Madrid, So Confused LOL in Belgrade and Derrida.pdf in Vienna.

Contreras convincingly performs the role of the curator as a force of nature—a nature that implies it allows the real-life connection that Kelsey fears will become extinct in our era of “hyperrelational decadence,” but a nature that also illustrates the unpredictability and fickleness that Kelsey expected.

It might appear that there are no limitations of political correctness in a conversation with Contreras, but that is certainly not the case. An endeavor to delve deeper into his process was cut short due to Contreras’s interpretation of pointed questions as indicative of my “Christian-American condescending gaze,” as he framed it, blatantly ignoring the fact that I am neither. Despite the honesty that characterizes his descriptions of his past drug experiences, hypothetical questions (ie. “Do you ever wish drugs weren’t important to you?”) offend him irrevocably.

Contreras employed a hyperconscious approach to respond to a request for further clarifications, resulting in his complete misinterpretation of the intended tone. In turn, he responded with a redundantly aggressive email that set the tone for our remaining interactions. Since I truly intended to learn as much as I could about his perspective and influences, I instantly apologized. My apology was genuine, and I once again reiterated my intention to construct his portrayal in utmost honesty. In theory, Contreras accepted this apology. In practice, the visceral responses he provided as clarifications indicated otherwise. The curator’s more-recent responses altered my stance towards the degree of the performative aspect of the Preteen Gallery tweets: both online entities thrive on belittling and disparaging others to accentuate their ‘superiority.’ READ MORE >

April 4th, 2013 / 11:03 am

On David Markson and Ben Marcus: An Interview with Ben Marcus

[Note: In 2000, Albert Mobilio of Bookforum asked Ben Marcus to interview David Markson. Though questions were sent, the interview was never completed. In 2012, after reading the questions on benmarcus.com, I decided to redirect them (with modifications) to Marcus himself. The interview took place via email.]

David Markson (1927-2010) was born in Albany, New York, and spent most of his adult life in New York City. His novels include Springer’s Progress, Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Reader’s Block, This Is Not a Novel, Vanishing Point, and The Ballad of Dingus Magee.

Ben Marcus is the author of The Age of Wire and String, among other books. His new book, a collection of stories, will be published in January of 2014.

Interviewer: Do you consider exposition to be deadly, inert territory?

Ben Marcus: There’s the infamous rule fed to beginning writers that you should show and not tell, but telling is one of the great and natural features of language—it’s part of what language was invented to do. It’s just that when telling is done badly—”she felt sad”—it’s conspicuous and embarrassing, it works only to remind us of the insufficiency of the mode. I always dislike hearing this rule, even if I understand why it’s given, but Robbe-Grillet is a perfect refutation of it. Sebald, Bernhard, Kluge, Sheila Heti. And of course Markson himself. Even the great narrative writers use exposition in masterly ways: Coetzee, Ishiguro, Eisenberg. READ MORE >

February 18th, 2013 / 3:19 pm

New Exercises in Style

For its 65th anniversary, New Directions has just released an expanded edition of Raymond Queneau’s classic Oulipean text, Exercises in Style, featuring 25 previously untranslated exercises by Queneau, as well as new exercises by Jesse Ball, Blake Butler, Amelia Gray, Shane Jones, Jonathan Lethem, Ben Marcus, Harry Mathews, Lynne Tillman, Frederic Tuten, and Enrique Vila-Matas. If you’ve never experienced Queneau’s encyclopedia of ways to write the same scene over and over, each time new, there’s never been a better time.

On Feb 21st, at 8:00pm, there will be a launch party for the book in Brooklyn, info here.

Below, we’re happy to feature a few of the new exercises from the book.

COQ-TALE (first published in Arts, November 1954)

Ever since the bistros got closed down, we just have to make do with what we have. That’s why, the other day, I took a pub bus, at cocktail hour, on the N.R.F. line. No point in telling you that I had a terribly hard time getting in. I even had a permit, but IT WASN’T ENOUGH. It was also necessary to have an INVITATION. An invitation. They are doing pretty well, the R.A.T.P. But I managed. I yelled, “Coming through! I’m an Éditions Julliard author,” and there I was inside the pub bus. I headed straight for the buffet, but there was no way to get near it. In front of me, a young man with a long neck who hadn’t removed the Tyrolean hat with a plait around it that he wore – a lout, a boor, a caveman, obviously – seemed set on gobbling down every last crumb that was before him. But I was thirsty. So I whispered in his ear, “You know, back on the platform, Gaston Gallimard is signing contracts.” And off he ran, the sucker.

An hour later, I see him in front of the Gare Saint-Bottin, in the midst of devouring the buttons of his overcoat, which he had swapped for some

—Raymond Queneau

Translated by Chris Clarke

January 31st, 2013 / 2:25 pm

‘I now pronounce you…’

Before the advent of modernism at the turn of the 20th Century, narratives usually ended with an engagement, a wedding, or a death. The protagonists of the relatively new novel form would find themselves paired off at the altar, or suffering their own demise. This narrative move demonstrates the power of marriage as a kind of full stop, a solution, a smoothing-over, the point that a relationship should be headed, even if it may fail on the way. It’s significant that although writers have since cast aside marriage as the standard form of plot resolution, marriage itself still remains a potent cultural force in the 21st century.

I want to make it clear that I’m talking about a Western cultural understanding of marriage, which over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries has become a predominantly secular affair, where subjects are able to freely choose their own spouses, and virginity and chastity are no longer prerequisites. This is based on current marriage trends, although there will always be specificities and areas of difference. It’s also important to recognise that the concept of marriage has an array of different meanings and traditions in other cultures, both secular and religious, which are far too vast for me to even attempt to discuss here.

December 7th, 2012 / 4:42 am

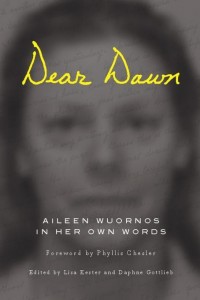

“I was thinking – to keep your left hand going – after I die – why not then – just pretend I’m still around…” — Excerpts from Dear Dawn: Wuornos in Her Own Words

On Thursday, we talked about Dear Dawn: Wuornos in Her Own Words, a collection of letters that Aileen Wuornos wrote from prison to her childhood friend Dawn Botskins. As a follow up to that post, which includes a conversation between editors Lisa Kester and Daphne Gottlieb, we’d like to show you some of the letters in the book. Our selection spans from the early 90s to the early 00s. Enjoy.

On Thursday, we talked about Dear Dawn: Wuornos in Her Own Words, a collection of letters that Aileen Wuornos wrote from prison to her childhood friend Dawn Botskins. As a follow up to that post, which includes a conversation between editors Lisa Kester and Daphne Gottlieb, we’d like to show you some of the letters in the book. Our selection spans from the early 90s to the early 00s. Enjoy.

Dear Dawn,

“Can you remember time!” Do you remember the fight me an greasy haired Penny Dole and I had at the front steps of troy Union Grade School . . . Do you remember when Lori, + Ducky got in that car accident . . . Do you remember a guy with real long jet black hair. Named “Black sheep” at the high school.? Well one day. Him and I went under neath a stair well near the new section they built that had swinging doors that head outside. Once you hit the bottom of the steps. Well he had a 4 finger lid of “Acapolco Gold” . . . we went under there to roll a big one and smoke it there. We heard footsteps coming down. But we figured that was just another kid on his way out to somewheres. So we finished rolling it. And started to lite it. And Low and Behold. It was the Principle. He looked at us both and said “Report to my office now” . . . . . Black sheep. Gave me the lid. And he started up the stairs. I said to the Principle. Bullshit! I aint reportin now where. Matter of fact. I quit school. Right now. He said. Then you get off of these school grounds right now wuornos. And if I ever see you on them again Ill call the police. You understand. ha ha ha! I walked out the double doors with the pot. And that was the day I quit school. What was really strange was that the principle knew I wasn’t living at home. But in the woods. I guess he admired me, for having the guts to still go to school, as a runaway, and living in the woods near your house. A trip huh!

Well last page. Gotta close er up. Take Care Dawn . . . I’m still surviven. A little crazy but still comin through. 4-now Love Lee

November 18th, 2012 / 2:46 pm

“And since I did all the talking. I talked about my fallen angels theory.” — Aileen Wuornos

Imagine you are shown a picture of yourself walking along a highway you have never seen. And now you are asked how you got there. Obviously you have to start running. As in running out of what you remember. Or running out, like losing it. And they want you to talk and talk, so immediately you’re talking back through hell. Talking back to hell. Or taking back hell. Maybe sing, you could call it, like hell. Whatever you want to call it and others call it for you. Insanity is a community decision, heroism is a community decision. Violence is the opposite of space. Everything I know about violence is also the nothing I know about violence.

The principal admired her for living in the woods, she wrote. She remembered all the cool black light posters, she wrote. God had it all recorded, she wrote. “Every women,” she wrote, “even adulesent, should learn Self defense, Also carry guns and know how to use them., when reaching a certain age. Like 21…” Some of the other advice she wrote was “just pretend I’m still around” and “ride through it all naturally” and write to keep the wrist from “stiffening up.” There were details she didn’t want to go into. She remembered which days the rain came down hardest. All of this she wrote in letters to her friend. She called the letters kites, which is a pretty common word in prisons. The prison only let each letter be a few pages, so she wrote more than a few letters. If you can still see a face on the other end of the wall, you can fill the wall.

In 1956, Aileen Wuornos was born Aileen Carol Pittman in Rochester, Michigan. Her father was in prison for the rape and attempted murder of a seven-year-old girl. They never met. He hung himself in prison when she was 13. At 14, she was raped while hitchhiking home from a party. She gave the baby up for adoption. By 15, kicked out of her grandparents’ home, she was living in the woods and sleeping in abandoned cars in the Michigan winter. She survived by way of herself. Her body was involved. She did have friends, and she spent most of the money she earned from sex work on them. Two of the movies made about her are called Damsel of Death and Monster.

In 1956, Aileen Wuornos was born Aileen Carol Pittman in Rochester, Michigan. Her father was in prison for the rape and attempted murder of a seven-year-old girl. They never met. He hung himself in prison when she was 13. At 14, she was raped while hitchhiking home from a party. She gave the baby up for adoption. By 15, kicked out of her grandparents’ home, she was living in the woods and sleeping in abandoned cars in the Michigan winter. She survived by way of herself. Her body was involved. She did have friends, and she spent most of the money she earned from sex work on them. Two of the movies made about her are called Damsel of Death and Monster.

While in prison for the murder of seven straight white men, whom she shot and killed in remote Florida locations, she told Phyllis Chesler “I raised myself. I did a pretty good job. I taught myself my own handwriting, and I studied theology, psychology, books on self-enhancement. I taught myself how to draw. I have been through battles out there raising myself. I’m like a Marine, you can’t hurt me. If you hurt me, I can wipe it out of my mind and keep on truckin’. I took every day on a day-by-day basis. I never let things dwell inside me to damage my pride because I knew what that felt like when I was young.”

READ MORE >

November 15th, 2012 / 12:02 pm

Valley of the Dolls

I’ll admit that I giggled when Miley cut her hair and her twitter fan said she looked butch. I laughed when Britney went loco and shaved it all off. Hair seems to be the number one method of rebellion for the Disney starlets, this host of young women who grow up in front of the camera with overly white smiles and innocent girlish good-looks (often dimples), and then completely implode in the most public way possible. Yes, of course, these girls seek out stardom, and there will always be young kids who will do anything to get on TV or have their fame moment online, particularly now in this image-saturated techno age. And there will always be parents who will push their child from the moment they can walk to be a triple singing-dancing-acting threat. But what really intrigues/confuses me is this idea of the spectacle itself, the way in which there is an intense focus placed on these young women as they mature from kids to teenagers to young adults: it’s a coming-of-age that comes with a side of anti-depressants and multiple rehab trips – but it serves as global entertainment – whether it’s taking place on the Disney set, or through leaked grainy mobile bra pics and indiscretions at the Chateau Marmont.

October 19th, 2012 / 6:45 am

The Boys from Oz

Australians have a history of distrust with the suburban space. It’s one that I think is far more ingrained than the ongoing American preoccupation with the suburbs. The abjection, otherness, decay and concealed violence of the suburban space, and the affect this space has on the Australian male, is an important part of the Australian imaginary. This is evident with the continuous repetition of these themes, particularly criminality and violence, in a whole host of recent films: Wish You Were Here (2012), Snowtown (2011), Animal Kingdom (2010), Somersault (2004), The Boys (1998) and Head On (1998).

I’ve chosen to talk about The Boys and Animal Kingdom because I think that they offer a distinct and unique portrayal of masculinity: one that is on the borderline, in between the public and private, criminality and legality, contained in an uncanny domestic space. The everyday suburban space is ruptured, undone and exposed as an unsettling site for a stifling and childlike male development, categorised by violence and the need to return to the maternal. This is the common trope in Australian domestic cinema ‘which finds expression in a distorted reflection akin to a hall of mirrors; each person staring back is undoubtedly familiar, but is in some way simultaneously emphasised, concealed and misshapen.’ (Thomas and Gillard, Metro Magazine, 2003)

September 27th, 2012 / 11:19 pm

William Giraldi’s Review of Alix Ohlin: A Failure in Four Parts

Background

Last weekend, William Giraldi’s New York Times review of two new books by Alix Ohlin blew up the literary twittersphere (which is to say that literally tens of people were talking about it). The discussion about Giraldi’s incredibly mean-spirited critique coincided with a debate about niceness vs. honesty in reviewing, started by an intriguing (though, in my opinion, somewhat alarmist) article at Slate. But Giraldi’s piece is irrelevant to the nice vs. honest debate and completely worthless to either side of the argument, since his review is not only dickish, but also dishonest.

August 21st, 2012 / 1:54 pm

I’LL DROWN MY BOOK: Part 5 (Talking With the Eds.)

While working on my initial review of I’ll Drown My Book last spring (2011), I posed a few questions to the editors. Here are some of their responses…

***

To Laynie Browne:

Many of the characteristics you give for Conceptual Writing, seem to me, be able to also describe what “good experimental writing” ought to be, in some ways. Though I’m sure we would agree on the problematics of the term “experimental,” and maybe more so with “good” and “experimental” juxtaposed, I’m thinking about some of the features you mention: “a recasting of the familiar and the found,” as defined by “thinkership,” often filled with “an assemblage of voices,” “process is often primary and integrative,” “the unknown and investigative are common impulses,” “the desire to reveal something previously obscured,” etc. It seems to me many experimental writing projects would share these characteristics. Might you agree? What makes Conceptual Writing stand out from other experimental writing projects? READ MORE >

June 8th, 2012 / 12:00 pm