DAVID LYNCH’S DESTABILISING AFFECT

GOOD DAY TODAY: David Lynch Destabilises the Spectator

GOOD DAY TODAY: David Lynch Destabilises the Spectator

By Daniel Neofetou

Zero Books, 2012

93 Pages, $14.95 (buy it at Amazon)

The initial conceit of Neofetou’s Good Day Today is one that I inherently agree with, and one that I think should be considered in larger terms of not only film studies, but an understanding of how to watch movies in general. As a theoretical construct it was first introduced to me in Cinema and Sensation: French Film and the Art of Transgression by Martine Beugnet, a brilliant study of affect found in the mileu of the “new french extremity,” the art house mavericks Bruno Dumont, Philippe Grandrieux, Catherine Breillet, and so on. While Beugnet’s book does lose itself to a final chapter devoted to a Deleuzean study of film & embodiment that, in my opinion, adds nothing to the first two-thirds of the study, overall the book presents and articulates, with careful, pointed examples, what cinema can do for the spectator.

Neofetou’s book, while seemingly not indebted to Beugnet’s book at all (something that I would argue is, in a sense, unfortunate) takes certain theories that have formerly been applied only to experimental (non-narrative) cinema, and looks at David Lynch’s films within this context. His thesis is that these modes of cinema, particularly within the diegetic sway of a narrative & representational film, serve to–as the title would suggest– destabilise, disorient the spectator, the viewer of the film. As such, the book offers a very close reading of a number of Lynch’s films–though the titles of note are, of course, Inland Empire, Lost Highway & Mulholland Drive–& the scenes therein, showing the reader just exactly how Lynch manages to simultaneously play with affect while still insisting upon the “rules” of narrative/figurative/”realist” cinema to the point where when the rules are broken, we are destabilised not because said scene doesn’t make “sense,” but because the scene violates the inherent logic of the film & undermines the authority of an omniscient narrative position.

And the book does this well. Neofetou, throughout the book, takes examples from a number of canonical experimental films (Meshes of the Afternoon, Flaming Creatures, Gidal’s Epilogue) and compares their techniques to the techniques of certain scenes found in Lynch’s films, highlighting both the similarities between the scenes & the differences that arise out of the context of the films as a whole. There’s also a brilliant chapter near the end of the book dedicated to the idea of Lynch’s use of pop-music, absent dialog, and sound, that is a great chapter in its own capacity in looking at the way audio works toward the viewer in a cinematic exegesis.

Another strong point of the book is that within his examination of Lynch as a filmmaker who works with affect more than representation, Neofetou does an excellent job of both rejecting and explaining this rejection of the idea that Lynch’s films are “puzzles” to be solved–closed films where there is a literal solution. This, of course, is ridiculous, and a repeated mode of viewing that I personally find insufferable because, as Neofetou points out that Sontag mentions in her essay Against Interpretation, this mode of viewing “blinds [the spectator] to the work’s sensual facets”.

The book is not perfect, however, and there are two major faults that certainly don’t kill the book, but strike me as perhaps frustrating. The first being a short 7 page look at Lynch’s films through the eyes of the ‘Bechdel Test,’ ultimately considering accusations of Lynch’s films as misogynistic. Unfortunately the chapter ends up sounding apologetic instead of actually engaging with the idea, as its idea loses itself in a self-aware politically correct feedback loop that undermines any sort of look, thus rendering the chapter as blank space in terms of critical thought. I’m curious as to its place in the book, as there are repeated comments regarding Lynch’s ostensible a-political stance.

Which, in a way, leads to my other complaints–the subtitle of the book, the copy on the back, leads one to believe that after introducing (& proving) the idea that Lynch destabilises the spectator, there is little suggested beyond this in the text itself. There are a lot of directions that this could be taken, and the copy suggests that the book will take this idea in the direction that it helps to shake the politically hegemonic mode of representation, which helps to destabilise the idea of binary, simplicity, homogeneity.

April 30th, 2013 / 3:58 pm

55 Points: Shoplifting from American Apparel

1. This is a review of the recent film adaptation, not the book, although I’ll also say a few things about the book.

2. I saw the film on 14 March at the Logan Theatre in Logan Square, Chicago. It was a special event. About 70 people were in attendance.

3. The director, Pirooz Kalayeh, was there, and I spoke with him before and after the screening. Brad Warner, who plays Tao Lin (or “‘Movie’ Tao Lin”), was also in attendance.

4. Pirooz gave me a poster and a button and a DVD copy of the film. Thank you, Pirooz!

5. I’ve read Shoplifting maybe half a dozen times. I’ve also taught it twice. It’s my favorite of Tao’s books and I consider it something of a masterpiece.

6. Some people persist in thinking Tao isn’t a stylist, but I think he’s a brilliant stylist. Although maybe people are nowadays more convinced of this? I don’t know.

7. As Tao himself has pointed out (see here for instance), all of his books are written in different styles, something that I think obvious when one really looks at them.

8. I suspect some people really aren’t looking at them.

April 15th, 2013 / 8:07 am

Spring Breakers?

Anybody else not that big of a fan of Spring Breakers? I didn’t hate it, but I also never felt that excited by it. It felt more like watching MTV mimicking Korine’s prior styles, which I guess is maybe part of the point, but if so I don’t care for the point. I imagine if it’d been listed as directed by Todd Phillips, and that doesn’t seem impossible, no one would have given it a second thought. Having seen Holy Motors shortly after, I can’t help thinking I wish that had been Korine’s next film somehow, at least in breadth.

Chasing the Red Herrings in Greenaway’s Z+OO: a symposium of myself

It starts with a crash. You do not see the crash. You hear it. You see the aftermath. Typical. A dead swan splayed over the hood of a white Ford Mercury. The first time I typed that, I typed Mercy. Different cars are very much different sorts of animals. Domesticated animals, of course. Crossbreeds. It is said that the different sorts of hominids did not, could not, cross. Put that in my zonkey’s ass. The woman driving the car, who will be accused of taking mercury to procure an abortion, is named Bewick. The Mercury is no longer produced. You could say it is extinct. It was Ford’s answer to the Buick, you could say it was a fake Buick, a car that would no longer be were it not for waning appeal among wealthy Chinese (the last Emperor drove one, so did my grandma). Rauschenberg was born in the same town as my mom. This scene, the first of A Zed & Two Noughts, looks like something he might have filmed in the sixties, if only he had combined his interests (visual & performance art) into film, the way he did with found objects, like his notorious American bald eagle (an animal that will be mentioned later in this film when a prostitute named Venus de Milo asks the zookeeper for the tail feathers of that bird in order to write a dirty story, the same zookeeper who will later threaten to tell the director of the zoo, who is in fact the director of the film, about the brothers bringing the dead dalmatian into the zoo because it is “an abomination”). But then Rauschenberg dealt with death in ways more conceptual, less actual. I remember riding in the back of my grandma’s Buick because it had a passenger-side airbag. I remember carefully visualizing my death. I remember oak trees. The accident happens on Swan’s Way. Way is one of the ten most common words in our language. Weeks ago, this surprised me. But it should not be surprising that the journey is more popular than the destination. We’re a restless race. We want tiggers in our tanks & Michael Nyman to speed up & O will he!

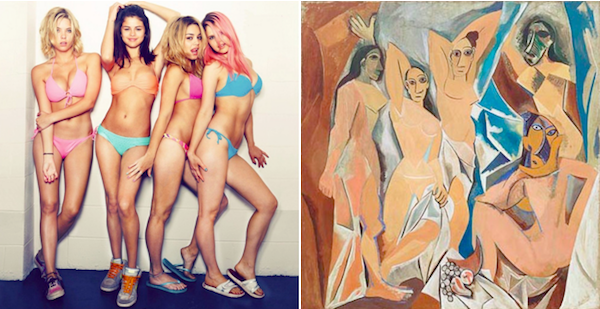

Spring Breakers

The controversy surrounding Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) lay not so much in its sexual inclination — to which most of Western painting, perhaps even religious, had been dedicated — but in the grotesque and primitive fashion the whores had been rendered. The painting may have been an antagonistic response to a more gentle work (Le bonhuer de vivre, 1906) by Henri Matisse, with whom the former had been in heated rivalry. It shows five prostitutes in a brothel in Barcelona, the still life at the bottom a phallic placeholder. Before racism, Europe simply eroticized Africa, where our artist had gotten tribal masks by which he was noticeably influenced. The offense, then, it seems, was less of a feminist encounter than an Anglo-Saxon European one; simply, we had been unwittingly drawn into bed with dark monsters from another land. As we gleefully await Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers, which promises to be Girls Gone Wild meets Cops meets every rap video ever made, we are teased with promotional images and film stills. And it would take Selana Gomez — our lady of $4 million net worth; 14,417,325 twitter followers (as of 3/10/13, 11:29 PST); inside whom Justin Bieber first became a man — to swiftly strike a pose that came before her, Madonna, and Marilyn Monroe. An animal, when threatened, will bring their hands to their face; to retract them beyond is to exert trust, the ultimate form of control. To disarm the gaze of its power. Good girl.

Couch commentary

That a couch in an average living room faces a television may be an invitation to become what we are watching, namely, a movie — that is, if our couples would just pay attention. Lateral domesticity begs to fall asleep. A man, reduced to emasculated flab, pleads for his unhealthy and coddled relationship to continue; the tacit repose of a couple engaged at their respective laptops seems precious; some bro fantasy of simultaneous bong and munchies with anthropomorphic hump pillow; the platonic diplomacy of former lovers newly registering the full radius between them. The couch may be an obvious place for contemporary dialogue, or its reticence, but there’s something peculiar about the camera choosing the very place of its artifice to peek into these lives, as if these movie directors took for granted — or were even ashamed of — the rectangular boxes in which their creations are manifested. Perhaps we find relief in seeing others situated as us. When a DVD ends, it reverts to the menu page consisting of some thematic snippet which goes onward in an infinite loop. One may lie there out of the remote’s grasp, too tired to hit ■. It is easy to lose track of time in the waiting room of habitual inception, the ▶ untouched. Every disc sheathed inside its tray is a silver sun waiting to rise, spinning out of control. Another reason to sit down, and pretend.

The collected films of B S Johnson are finally getting a video release

Entitled You’re Human Like the Rest of Them. Both DVD and Blu-Ray formats (Region 2 / PAL). Comes out on 15 April. Includes:

- You’re Human Like the Rest of Them (1967, 17 mins): multi-award-winning tale of a teacher confronting his own mortality [click here & here for more info]

- Paradigm (1968, 9 mins): William Hoyland gives a performance of supreme virtuosity in this arresting experimental film

- The Unfortunates (1969, 15 mins, DVD only): Johnson brings aspects of his book to life in this short BBC TV film

- Up Yours Too Guillaume Apollinaire! (1969, 2 mins): humorous animated take on the calligrams of the famous poet and eroticist

- Unfair! (1970, 8 mins): provocative agitprop piece with Bill Owen

- March! (1970, 13 mins): documentary made for the ACTT union

- Poem (1971, 1 min): poignant short set to the words of Samuel Beckett

- B. S. Johnson on Dr. Samuel Johnson (1972, 26 mins): a learned and full-bodied appreciation of the great writer

- Not Counting the Savages (1972, 29 mins, DVD only): Mike Newell s adaptation of Johnson’s intense play, made for BBC TV’s Thirty Minute Theatre

- Fat Man on a Beach (1974, 39 mins): part documentary, part creative exploration, this was a highlight of 1970s TV programming

This should be enough to make anyone’s Fat Tuesday.

& if you haven’t read B S Johnson, then what can I say but you’re missing out.

Bonus movie review: I watched the 2000 movie adaptation of Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry, one of my all-time favorite novels. I’m sorry to report that it was awful.

The 474 Best Movies of 2011 & 2012

Well, we had all that data on the most critically-admired films from 2011 and 2012, and I don’t know about you, but I couldn’t resist compiling it.

In 2012 we counted 240 films that made critics’ best-end lists. In 2011 we counted 250 (not, as I originally miscounted, 248). They add up not to 490 as you might expect, but to 463, because there was some overlap between the two years. (27 films, we can now tell, made year-end lists in both years.)

. . . And, actually, since I posted about the best 240 movies of 2012, the Year-End site I draw this data from has added four more critics’ lists—in particular Jonathan Rosenbaum’s. So I’ve folded in those results as well, yielding 251 films in 2012, 250 in 2011, and 474 films total between those two years. Though remember, of course, that this is all very approximate!

Now, because we’re dealing with more votes for 2012 than for 2011 (77 critics/organizations vs. 58, yielding 1293 mentions total vs. 1072), we should expect there to be a bias toward films from 2012. Furthermore, I predict that bias will be most evident in the most top-rated films from this year (since that’s where critical opinion concentrated).

So here are the 13 most-mentioned films from the past two years. [The format is # of mentions, title, (director)]: