1. Boyhood resists most attempts to analyze it outside the circumstances of its creation. Richard Linklater has filmed a group of actors every year or so for more than a decade, collecting episodes that tell the story of a young boy, Mason (Ellar Coltrane), and his family. The success (and the complications) of this approach and the events depicted on-screen compete for our attention, inasmuch as we can separate them. There’s no easy engaging with Boyhood purely on the level of plot and character.

2. Linklater’s experiment gives him creative latitude with the coming-of-age story that storytellers don’t always have (or don’t always grant themselves). Mason’s mom (Patricia Arquette) marries and divorces an alcoholic, then marries and divorces an alcoholic once again. In another film, this instance of repetition might play as laziness on the part of the filmmaker; in Boyhood, it plays as a function of the film’s verisimilitude. (‘That kind of thing happens in real life,’ etc.)

3. Boyhood also complicates the manner in which a viewer distinguishes a performer from his or her character, especially in the case of the film’s child actors. We are seeing these people grow up—quite literally, if only to a point. This is unsettling at times, seeing the continued physical development of a person without having any insight into his or her actual life. And Boyhood is much better at persuading us to invest in what’s on-screen than the latest item on your Facebook newsfeed about a distant cousin’s kids.

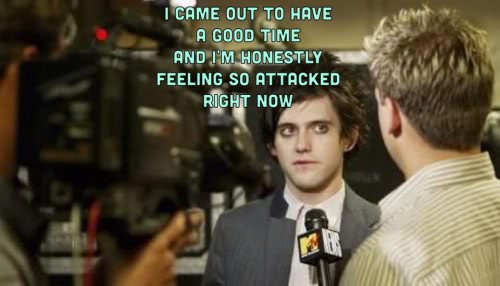

4. Between Boyhood’s documentation of the year-by-year aging of its young actors and the film’s general verisimilitude, Linklater’s decision to preserve—on film—Ellar Coltrane’s unfortunate late-teens facial hair is at once cruel and perfectly appropriate.

5. The choice also demonstrates the perils of verisimilitude. We don’t often see facial hair this ugly in cinema; underdeveloped in a manner that makes it also appear somehow unclean, a manner that communicates its own basic misguidedness. Although Coltrane’s wispy attempted goatee makes contextual sense, it also registers (perhaps too intensely) as an aberration.

6. Boyhood really only becomes a film about boyhood after an hour or so. Until that point, the film’s attention belongs to Mason’s family as a unit. Of course, many young children spend more time with their siblings and/or parents than older children do. But I missed the focus on Mason’s larger family once it was gone. A curious viewer might wonder when and how Linklater decided on the boy as his subject, when he decided on his film’s title, etc.—again, even matters of plot will likely lead the curious viewer back to thinking about the film’s production. The conceit is inescapable.

7. A curious viewer might also wonder if Linklater merely felt more comfortable telling the story of a young, male aspiring artist than he did telling a more holistic family story—or if he worried that audiences wouldn’t turn out in the same numbers for a similar movie about a young girl.

8. Patricia Arquette in particular has an arc that’s an arc as legible as Mason’s and arguably more compelling. Linklater never abandons Arquette’s character as she navigates higher education and single motherhood, but it’s a real sadness that the movie becomes more conventional in its focus as it goes on. We can see other films within this one, and that sense of possibility is bittersweet.

9. Though in fairness to Linklater, if one looks at the range of films he has made while not attending to Boyhood—the Bad News Bears remake, A Scanner Darkly, Bernie, Before Midnight—then the narrative coherence and tonal consistency of Boyhood is remarkable, whether or not the film becomes another story of a young white dude finding himself.

10. Mason’s father (Ethan Hawke), a wannabe musician, comes and goes during the first years of Mason’s life we see onscreen. He’s a consistently inconsistent presence, someone whose life as an artist has not gone as planned—which makes his scenes valuable counterweights to later scenes of Mason discovering his own artistic ambitions.

Forest of Fortune

Forest of Fortune