Sick with Anxiety: On Ben Marcus’s Leaving the Sea

Leaving the Sea

Leaving the Sea

by Ben Marcus

Knopf, January 2014

288 pages / $25.95 Buy from Amazon

“I’d been thinking for years about language as a toxic substance,” said Ben Marcus in a 2011 interview with HTML Giant. “Language itself making people sick. Speech and text, all of it poisonous.”

He continued, “I seem to write about language a lot. Language as a physical substance with deviant powers: a powder, a drug, a wind, a medicine. I can’t really help it.”

Ben Marcus is obsessed with language on a sort of sadomasochistic bent. Consider this invective: “In English, no matter what you said, you sounded like a coddled human mascot with a giant head asking to have his wiener petted…”

And, “English, in which every word was a spoiled complaint, a bit of pouting…”

And, “…a whiner’s tongue.”

And, “At least overseas he didn’t speak much English.”

And, “….he spat his useless English.”

All of these are taken from Leaving the Sea, the new collection of short stories from Marcus, who is bound and determined as ever to make us sick with language. Leaving the Sea is divided into six sections on loose formal and philosophical grounds, and in loose order of obscurity and opacity.

The collection begins safely, with Marcus’s most accessible work, although there isn’t much in the way of traditional resolution even here. The key to any good relationship, the writer/reader one included, is a managing of expectations, and nowhere in even his most outwardly inviting writing does Marcus hint at anything that suggests closure and a case of the warm-and-fuzzies.

Another consistency: Marcus’s characters are consistently on the wrong side of power balances, often for reasons unclear. The opening story, “What Have You Done?” features a protagonist who has returned “home” for a family reunion of sorts, only be shunned and vilified by a family that seems equally bemused by and afraid of him. We see hints of an “old Paul” boiling over throughout the story, but the title of the story remains a taunt, as we never quite find out what Paul did. (To consider this a spoiler, by the way, is to miss the point of Marcus’s writing, which can be very much like tantric sex sans orgasm. I mean that in a good way.)

The characters we meet in Leaving the Sea are often achingly sad, borderline alexithymic, and resigned to a fate over which they have no control. Despite the harsh sense of determinism, Marcus’s characters all seem to feebly make attempts to control what little they can. Fleming in “I Can Say Many Nice Things” is a serious writer forced to lead a creative writing seminar aboard a cruise ship for financial reasons while trying to resist the temptation of an affair with an enthusiastic student as a small act of mitigation against his bitter wife back home.

In “The Dark Arts”, Julian fends off nighttime invaders in a Düsseldorf hostel while undergoing experimental treatments for a rare immune disease — an “allergy to my own blood”, he calls it — all the while waiting for his girlfriend, who has yet to arrive from France after a lover’s quarrel. When she does materialize, cold and aloof, we’re left wondering if Julian might have been better alone, a thought not lost on him. “Had anyone,” Julian wonders at one point, “ever studied the biology of being seen? The ravaging, the way it literally burned when you fetched up in someone’s sight line and they took aim at you with their minds?”

If it is a subterranean discomfort the reader feels in the first three stories, the last of Part One, “Rollingwood,” carries it to full nausea. Mather is the father of a sickly child, afalter in every aspect of life, and seemingly unable to summon the strength to fight back against an ex-wife and a potentate boss who appear supercilious towards his continued being, particularly when his usefulness runs out. What transpires leaves the reader feeling gutted, somehow disappointed to the point of sickness, although one could hardly call it a visceral story. The language is plain, inviting even, but weighted with sadness.

Part Two consists of a series of interviews with a series of cultural tastemakers/gurus who believe they hold the key to a happier life by way of shunning the adult world. One, in a not-so-subtle allusion, believes that perhaps we’d all be better off in a cave, though this one has no light by which to project any shadows at all.

Parents — and more specifically, the child’s Stockholm-syndrome-like sense of duty towards them — dominate Part Three, which is comprised of two stories. The first is a meditative essay by a man who wonders for the length of the story how his actions or inactions might hasten or delay the death of his mother. The story is rife with a sort of realistic morbidity, particularly in the passages that describe different scenarios in which the mother’s body might be found, and after how long. The second story of Part Three, “The Loyalty Protocol”, takes place in another of Marcus’s miasmatic hinterlands between our world and a bleak alternate reality. During a series of drills for an unspecified threat, Eddie must choose whether or not to break rank and bring his senescent parents along, who have not been called to the rendezvous point.

Part Four is comprised of a single story, “The Father Costume”, which is particularly unsettling in not only its bizarre, arcane imagery, but in its ever-shifting set of linguistic paradigms, with characters all seeming to speak a different language and there being no real common phrasing to latch on to, ensuring the reader never has a complete grasp on the world Marcus has created. (The story, it should be noted, would appear to be a reworking of a 2002 book of the same title by Marcus and fellow author Matthew Ritchie.)

It’s often hard for a reader to determine whether a writer is challenging them, or just fucking with them, and the queasy feeling one gets through this story makes it either one to deep read or skip altogether, depending on your predilections as a reader. All the same, it seems like just the sort of story Marcus had in mind when he said, in the same interview:

“In the end I want to write things that I don’t know how to write, because this seems to command the most energy and desire and attention from me. It makes me sort of sick with anxiety. When I’m uncomfortable and confused and curious I tend to try much harder to figure things out.”

The language games continue in Part Five with a set of stories that seem aimed at putting the mundane into new dialectical contexts. “First Love” is a stumbling attempt by a nameless narrator to frame his amorous attempts in a language we might understand, even taking the time to tell us, “The word body used to refer to the evidence left behind that someone has died.” As with many of his stories, Marcus refuses to tell us whether the “used to” here implies a futuristic world, or merely the shattering of an individuals that renders language, at least in the objective sense, largely moot, a la Kate in Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress. Each story of this section poses that same question, as family life and relationships and lovemaking are all forced through the cracked lens of Marcus’s devising.

February 24th, 2014 / 11:00 am

On David Markson and Ben Marcus: An Interview with Ben Marcus

[Note: In 2000, Albert Mobilio of Bookforum asked Ben Marcus to interview David Markson. Though questions were sent, the interview was never completed. In 2012, after reading the questions on benmarcus.com, I decided to redirect them (with modifications) to Marcus himself. The interview took place via email.]

David Markson (1927-2010) was born in Albany, New York, and spent most of his adult life in New York City. His novels include Springer’s Progress, Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Reader’s Block, This Is Not a Novel, Vanishing Point, and The Ballad of Dingus Magee.

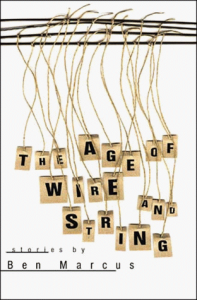

Ben Marcus is the author of The Age of Wire and String, among other books. His new book, a collection of stories, will be published in January of 2014.

Interviewer: Do you consider exposition to be deadly, inert territory?

Ben Marcus: There’s the infamous rule fed to beginning writers that you should show and not tell, but telling is one of the great and natural features of language—it’s part of what language was invented to do. It’s just that when telling is done badly—”she felt sad”—it’s conspicuous and embarrassing, it works only to remind us of the insufficiency of the mode. I always dislike hearing this rule, even if I understand why it’s given, but Robbe-Grillet is a perfect refutation of it. Sebald, Bernhard, Kluge, Sheila Heti. And of course Markson himself. Even the great narrative writers use exposition in masterly ways: Coetzee, Ishiguro, Eisenberg. READ MORE >

February 18th, 2013 / 3:19 pm

An interview with Colin Winnette regarding his new short story collection concerning animals, “Animal Collection”

ADJ: Hi, Colin.

CW: Hi, Adam.

ADJ: Let’s talk about your new book, Animal Collection.

CW: OK, but I think Adam Robinson has already posted something. Does HG have a policy against there being two posts on the same topic?

ADJ: No, it’s OK so long as both guys are named Adam.

… But let’s you and I make small talk, instead. You moved to San Francisco recently. How’s that been working out?

CW: I went to Target today for bookshelves—

ADJ: They have Targets in San Francisco?

CW: They do! The San Franciscan Targets.

ADJ: Have you heard what James Howard Kunstler said about Target?

CW: No, what?

December 10th, 2012 / 8:01 am

The 2012 Realist Sex Novel Kerfuffle (a response to Blake and Stephen, involving also cowboys, Atlas Shrugged, and the Franzen/Marcus debate)

“Ho hum, I profess an interest in these cavorting sea nymphs only inasmuch as I can use them to allegorically comment on the Human Condition.”

Blake has stated, over at Vice, that he doesn’t want to read any more books about straight white people having sex. Stephen has stated, right here, that he is prepared to read many more novels about people fucking. There are substantial differences in these claims that we could pause to examine (“don’t want to read” vs. “am prepared to read”; “straight white people” vs. “people”; “sex” vs. “fucking”), but forgive me if I let those subtleties drop. Because I would rather observe that, if this is the scope of the debate, then it’s akin to one person saying, “I am tired of books about dogs, and no longer want to read more novels about them,” to which someone else replies, “I’m still willing to read some canine fiction.”

Recast in that light, it’s easy to see that neither person is right or wrong. How could they be? It is simply a matter of taste. One man has gotten tired of all those dog books. The other man is not yet so tired. The literary market, no doubt, will cater to them both. And perhaps, over time, demand for dog-free writing will grow, and drown out the pro-dog side, and the market will shift and, for some time, it will be hard to come by a copy of Marley and Me. (Here it might be helpful to replace “dogs” with some other thing, like vampires, or zombies, or alt-lit.) But through it all, one’s preference is perfectly free to steadfastly remain one’s preference. What’s not at stake, in other words, is the right to like whatever you like. The books you read say something about the person you are, and you should be proud of whoever you are! Display your chosen book(s) on the train to signal your affiliation with one of this nation’s many vibrant subcultures. Who knows? Another member of that subculture may spot you, in which case you can exchange nods, smiles, kisses! What’s more, today, thanks to the Internet, you can even make a list of the books that you like, then talk with fellow fans! (There are even web-sites devoted to this!)

Let’s try thinking instead about this argument in terms of genre. A new cowboy movie has comes out, and you and all of your friends go see it. Afterward, you’re wondering whether it’s any good or not …

Fan Mail #4: Ben Marcus

Dear Ben Marcus,

I just finished The Flame Alphabet. I woke up early on a Sunday morning to finish reading. And it was magnificent. I have read your books, or several of them at least. I read Age of Wire & String and Notable American Women the summer before starting grad school. They are audacious books, the syntax unlike anything I’d read before – call me a limited reader, of course, I’ve since read a lot more and come to understand its lineage – I wanted to emulate your style, your language, the way you created complex narrative by parataxis. I thought you were a fearless writer, and back then, I was young and afraid, although I didn’t show it in workshop, I wanted to be liked, as we all do when we’re young and insecure, but you, you were brazen, your writing was full of effrontery, and that’s what I wanted most in my writing. In short, you were an inspiration, maybe the biggest and most influential to me as a student.

“When he was nineteen, writing La Doublure . . . Roussel felt a literal brilliance running all throughout his person, his writing implements, and his room. The light was so dazzling he had to draw the curtains, afraid that anyone who saw him would be blinded by the rays streaming out of his face.” — Ben Marcus

A ham is proud of cocoanut.

A CLOTH.

Enough cloth is plenty and more, more is almost enough for that and besides if there is no more spreading is there plenty of room for it. Any occasion shows the best way.

….

A TIME TO EAT.

A pleasant simple habitual and tyrannical and authorised and educated and resumed and articulate separation. This is not tardy.

….

APPLE.

Apple plum, carpet steak, seed clam, colored wine, calm seen, cold cream, best shake, potato, potato and no no gold work with pet, a green seen is called bake and change sweet is bready, a little piece a little piece please.

A little piece please. Cane again to the presupposed and ready eucalyptus tree, count out sherry and ripe plates and little corners of a kind of ham. This is use.

[from Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein]

Fantasies of Trauma and the Experiment of Coherency

The Flame Alphabet

The Flame Alphabet

by Ben Marcus

Knopf, Jan 2012

304 pages / $26 Buy from Amazon

Ben Marcus wrote this book, which is to say he either typed it into a computer or used a stylus, pen or pencil to scratch pigment into a page or roll of paper—the tools available to us humans at our particular anchor in time.* He did this in roughly a year, after developing the concept: a man—through his own somewhat distorted lens on reality—relates his recent experiences in a world wherein language, spoken and written, is discovered to harm its producers and recipients. I will try not to ruin it for you, but the inhabitants of this world eventually determine that the formation of meaning itself—the moment of insight, in which the gestalt of the lexeme coalesces in the mind of the listener/reader—is the problem; i.e. when you understand a word, you become sick: and more words, more understanding makes you sicker.

August 29th, 2011 / 12:00 pm

“Intercourse with Resuscitated Wife” by Ben Marcus

I read Notable American Women before I read The Age of Wire and String, so despite my being somewhat familiar with Marcus and his interviews and his writing, I still wasn’t quite prepared for the kind of ‘language monsters’ he had packed into those 140 pages when I opened the book for the first time in the summer of 2006.

I read Notable American Women before I read The Age of Wire and String, so despite my being somewhat familiar with Marcus and his interviews and his writing, I still wasn’t quite prepared for the kind of ‘language monsters’ he had packed into those 140 pages when I opened the book for the first time in the summer of 2006.

And although the book begins with a sort of prologue, or ‘argument,’ which describes the book as a ‘life project’ meant to catalogue the age of wire and string, I will always think of the opening sentence of “Intercourse with Resuscitated Wife” as the warning shot, a language bunch that reoriented my understanding of how a parcel of words might be arranged in unusual ways.

The dropped articles, the potential comma splice, the archaic tone, the oddity described by the text, all of these I might have seen before, but never in such a sustained and tightly controlled way as this, and not in a contemporary landscape. And furthermore, I hadn’t yet become aware of many of the precursors who made such a collection possible. So to read this first sentence was a bit shocking for me, but in a good way, and helped me take greater care in my reading and writing from then on.

Intercourse with resuscitated wife for particular number of days, superstitious act designed to insure a safe operation of household machinery.