Walking with Dog & Sylvia

Nothing is more difficult than lashing a vagrant mind suddenly into long self-imposed stints of concentration.*

See the trees, the sidewalk, the trash can turned over, the Auburn flag, the dirty awning, the abandoned tricycle that will never not suggest something sinister. See the leaves, the dried ones on top and the molted ones beneath. See the neat ranch home, the Spanish colonial, the craftsman. Barking, birds, voices. Don’t think about what anything reminds me of. Don’t think about my childhood. Oh, my God–daffodils. Never not shocking with their yellowness, their alien mouths. Stop thinking about Sylvia Plath. Stop thinking about trying to write about her, the experience of re-reading her, the sex scene in THE BELL JAR that causes Esther to hemorrhage in a historical way, the rarest sex in the universe, the day-off-from-the-mental-hospital sex, the sex that punishes, the sex that touches death. How can the bleeding out not symbolize Plath herself, her genius, the violence she must have believed was embedded in her own ambition, in the very anatomy of female ambition.

So many cracks in the sidewalk, it would be impossible to play that game. Forgetting to remember and remembering to forget yield the same result: forgetting. A bird, another bird, so many birds. Too many birds today. How a certain number of birds signifies spring but one more than that number means something terrible is about to happen.

I want to live each day for itself like a string of colored beads, and not kill the present by cutting it up in cruel little snippets to fit some desperate architectural draft for a taj mahal in the future.

I am not an ‘in the moment’ person. The moment pains me with its borderlessness: how long will this last? When can I call it ‘over’? When can I call it the thing that came right before the real thing? When I was a child I sat in the church pew and was transmogrified by my longing for the service to be over. I mean I felt my blood blacken with disquietude, my limbs actually tingled. Sit still, my mother would say, but I would be sitting absolutely still. She could feel the friction in my mind, in my body, and it broke her concentration. Now, when I need to endure something I don’t want to endure, or when I need to wait for something, which I am still terrible at, and I can’t read or look at my phone, I try to pray, for something to do, and because that childhood pew was a crucible where my early ideas of God and suffering and forbearance and waiting got forged.

I’m newer to breathing as a form of coping. I used to become angry when people would talk about deep breathing. I like my breaths fast and shallow. Stop telling me to breathe, world. Stop telling me to slow down. Now I tell myself to breathe, to slow down. Mailbox, mailbox, crushed can, tire-flattened box of Eggos that must have escaped the recycling bin.

I catch up: each night, now, I must capture one taste, one touch, one vision from the ruck of the day’s garbage. How all this life would vanish, evaporate, if I didn’t clutch at it, cling to it, while I still remember some twinge or glory.

My dog–a phrase I never thought I’d say–sniffs everything. As though every day he sets out with one goal: to sniff every single thing. I pull him along, before remembering that I’m not supposed to be hurrying, I’m supposed to be pretending that time doesn’t exist, that all of these things around me are the miracles they’d be if I were a better person, or an animal. A chimney. A brick. So many bricks. I can’t fathom being tasked with building a house, or even just making a single brick. Trees, plants, grass–so much green and I only have the barest understanding of photosynthesis, of the very air I’m abusing. I have no practical skills, my God. Look at those bricks and meditate on the people who know what to do with them. Look at the litter without judging it. Stop judging the litter. The well-swept porch, the shabby car. This is not a cookie-cutter neighborhood. This is a real neighborhood. There is so much to see, if I could just stay with it, stay in the seeing, in the indexing, and out of the dictionary part, where meaning must be ascribed, or the memory part, where connections must be drawn. My dog eats garbage.

I keep believing that the world is loving because I am. I keep waiting for something to jump out of the bushes and harm me, but nothing harms me like I harm myself.

There is a certain clinical satisfaction in seeing just how bad things can get.

*All italicized portions are from The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath, ed. Karen V. Kukil

25 Points: Mad Girl’s Love Song

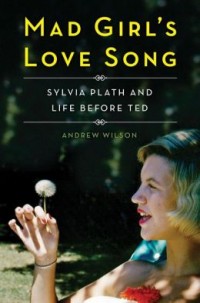

Mad Girl’s Love Song

Mad Girl’s Love Song

by Andrew Wilson

Scribner, 2013

369 pages / $30 buy from Amazon

1. After reading the Bell Jar and the biographical note in the back, the next piece of information about Sylvia Plath that I encountered was the only point of reference I had about her for a very long time. Alice Miller’s For Your Own Good features an essay called “Sylvia Plath: an Example of Forbidden Suffering,” in which Miller illustrates a scene of young Plath presenting to her mother and grandmother a pastel piece on which she has worked hard. The ebullience she demonstrates in showing off her achievement made a searing impression on me—I was not used to seeing female artists proud of their work; I was used to seeing them compromised and unfulfilled. The conclusion of the scene is equally powerful and so devastating, it remains my primary reference point regarding Plath as a depressed person: when her grandmother stood up, she smudged the pastel enough to ruin it. Plath’s flat affect, her inability to situate her disappointment where it belonged, has never not occurred to me when I’ve read about her, even though this scene does not recur with the canonical relish of, like, the St. Botolph’s Review launch party. By virtue of this scene’s inclusion in Andrew Wilson’s Mad Girl’s Love Song, I was swayed at first.

2. Plath’s writing is very important to me, and I love biographies where she is treated as the inexhaustible writer she was. As a subject, though, the way her work is so visceral, so loaded with the feelings that connect her to contemporary readers, that access overwhelming emotion, when she was remote, blank, totally affected: that I find riveting. Death notwithstanding, the more accessible her work, the less accessible she was. One cannot experience the closeness with her as a subject that one feels through her writing.

3. Although I bought and read the book because it’s about Plath, I am reluctant to use the biography as a means to discuss her because her work is more interesting than she is, so there’s that shame: why not talk about the work? In Wilson’s case, I do agree that the events of her young life are unfairly glossed over when she was so productive and disciplined so early, and for that I was excited to read Mad Girl’s Love Song.

4. The people in proximity to Plath aren’t ghosts here, either. Wilson talked to people who remembered her petulantly in some cases and fondly in others, and all vignettes get a greater sense of who they were than who she was, which makes for a livelier telling than what occurs from corralling facts from her archives—how real personalities generally unmoved by her achievements react to the young, raw person who remains animated in their pasts.

5. Her sexual voracity is emphasized as soon as possible, and much dwelled on are the rape fantasies she confessed to correspondent Eddie Cohen. The sole editorialization by the Wilson surrounding these incidents—which occur throughout the book—is: “We have to remember that Sylvia was a young woman overloaded with a huge store of sexual energy that she was not allowed to express…” This is pretty remarkable considering how Wilson handles other events.

6. Besides the unprecedentedly thorough examination of Plath’s childhood and Smith College years, the big news of this biography is how she demonstrated the tendency to self-harm in the immediate aftermath of her father’s death, and that self-harm manifested in the deliberately extreme and suicidal manner of attacks on the throat. This new fact, central to Mad Girl’s Love Song’s purpose, was the point at which I started to feel like I was reading Us Weekly not in terms of content but in terms of how I felt like, why am I reading this, I am so full of shame.

7. An aside: in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Laura Palmer knows she’s about to die. Agent Cooper points out how, while she did not commit suicide, she did consent to and prepare for her murder. In her last days, she warned her best friend, Donna, not to wear her stuff: don’t fetishize me, she was saying, don’t make me into a symbol or a set of aspirations, don’t channel me as a transcendent measure to get free from your boring suburban life; I am a broken person and I am in so much pain. It’s an incredible privilege that the dead girl gets – the audience is not only used to her as a structuring absence, but they’ve also seen Donna access her sexual awakening by wearing Laura’s sunglasses. Mad Girl’s Love Song is the kind of book Donna would have written about Laura Palmer: endowing talismanic power to incidents and items in lieu of presenting the facts of her life and why she is worth discussion.

8. “Although I thought [Plath] might be awfully good, I was on the cusp a little on how she might fit in. Her behavior was almost a performance, which I found a bit of a problem. You might be there another day and find an entirely different personality.” – Gigi Marion, college department, Mademoiselle

9. Eddie Cohen chastised Plath for her complete inability to be spontaneous, and the roots, extremes, and repercussions of her constant performance are explored fully in Mad Girl’s Love Song. Mademoiselle‘s ambivalence about Plath provides a great launching pad for a vital paragraph on the magazine’s own artificiality. The way the magazine fully constructed the “New York” experience that the co-ed guest editors has for too long gotten off without comment, but it is so much a part of what powers the Bell Jar, to wit, the conclusion may justifiably be drawn, it made a serious impact on Plath. It’s one thing to put on a face and look the sweetest and the most congenial, it’s another to play along with the mass hallucination that high-rise parties with hired dates have any place in reality.

10. “It was a lunch designed for the girls to get to know one another a little better, and we were at that stage where we were watching one another very carefully, all of us groping to see what we should do, how we should behave. Very shortly after we were seated—at this nice table with a white table-cloth—a large bowl of caviar was served. The caviar was supposed to be for everyone on the table, but Sylvia reached out for it, pulled it in front of her, and began eating. She proceeded to eat the whole bowlful of caviar with a spoon. I remember thinking to myself ‘how rude’…” – Ann Burnside Love, guest merchandise coordinator READ MORE >

April 2nd, 2013 / 2:23 pm

House Wife Blues: Plath, The Bell Jar, and Writerly Neuroses

Yesterday, my boyfriend and I were out walking the dog, and I was feeling shitty about work as usual. Rounding the corner where the Bay meets the roadway, sun setting pinkly, I blurted out, “Sometimes I just wish I could be a housewife.” He looked at me and said, “Me too.”

That was the end of it. Which pissed me off even more. I wanted to have a legitimate conversation about what it means to be a housewife (which, by the way, I could never be in the 19050s sense), the fact that it’s not even an option anymore for most women. We’re worker bees now, too. It’s only fair. If I want to stay home, which I kind of do, I have to figure out a way to pull in enough income to pay the mortgage on the house I bought all by myself. I have to be able to pull my weight. Not to mention take care of the dogs, do the laundry, make dinners–all because I’m home, which somehow still means, not doing anything at all. My boyfriend would never say or think these things, by the way, but I would. I struggle with these concepts because I would feel guilty if I had the luxury to write. As if writing isn’t work. Writing poetry isn’t work, it’s what you do in your spare time.

In her essay “The Bell Jar at 40,” Emily Gould writes of Sylvia Plath:

Plath & Hughes

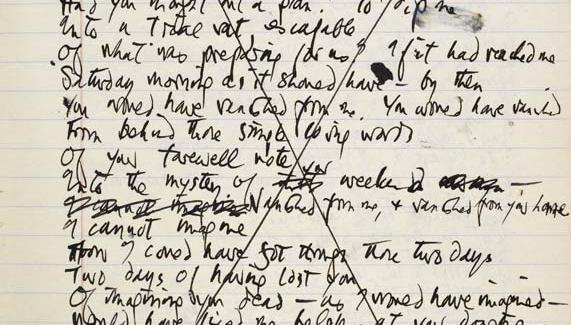

Ted Hughes draft of "Last Letter"

Newly released by the British Library archive, and published in the New Statesman, Ted Hughes’ poem “Last Letter” recounts the three days leading up to his wife Sylvia Plath’s suicide, ending with the moment he is informed of it. Fervent Plath fans, of the kind who vandalized her tombstone to remove his name from its inscription, may or may not receive his anguish well, for he is commonly blamed for her suicide, given that their break-up (initiated by him) immediately preceded it.

It is dangerous when fans, readers, and critics meddle in the private lives of writers, for their biographies, poetry, and nonfiction are all a kind of fiction; we can never know them, let alone judge them, the way we can never know ourselves. For anyone who thinks words, of any sort, lead to truth, I say: look outside. It is odd how Ted Hughes can finally be vindicated, as if such a pardon was ever needed. He had a severely depressed wife who killed herself, much like Leonard Woolf, except the former was also famous, so more meaning was attributed, relished, to their drama. Biographies are highbrow soap operas.

Above All, We Believe in Magic: A Week in Review

Monsieur Ponge avec une cigarette

My week, but maybe you’ll relate.

Assigning Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics is really the best thing you can do for anybody.

“Fox and Whale, Priest and Angel,” by Russell Banks is travel writing, but it’s also about vision. So is nearly every travel piece I love. They all find the spark in a landscape and look into it and worship it—especially if the spark has been induced by altitude sickness (Banks) or nostalgia and maybe mushrooms (Jason Wilson, “Whistling at the Northern Lights”).

I learned this week that CK Williams does a better job of translating Francis Ponge than the translations I’m reading in Models of the Universe when a student brought me Francis Ponge: Selected Poems. That Ponge is masterful at conflating disparate objects. That you can make opening a door sexy if you’re Francis Ponge. I learned the definition of peduncle from the not-so-good translation of Ponge’s poem, “The Candle.” I learned that Ponge wasn’t interested in titles so much. And that maybe I’m having a love affair with the prose poem.

I read and discussed poems from Kathleen Ossip’s The Search Engine with a very cool student. I learned that the only thing more depressing than a Plath poem, is a cento of lines by Plath and Sexton. I remembered how much I love Plath. Thanks, Ms. Ossip. And thanks for these lines, among others:

I’m eating bread and water

alone, naked as the day

I was born. Hey, Ma,

I say, though she’s not

around, you won’t believe this.

Physicists say that in

addition to a yes and a

no, the universe contains a maybe.

Off in the distance, under the stars,

she moves like a platypus,

neither here nor there.

I read In The Year of Long Division by Dawn Raffel because Alec Niedenthal told me to. He and I will argue about this book soon enough. I’ll report back. But I learned that I like my dialogue to say something. And I remembered how important titles are.

Other very important things I learned this week: I love copyediting; I want a pet crow; I can’t stop thinking about the first season of Friday Night Lights; and I’m pretty sure I believe in magic.

Variations on Hating: A Miniseries: Dido Merwin on Sylvia Plath

Dido Merwin lived in one of these beautiful houses at some point in her life. In the biography Bitter Fame: A Life Of Sylvia Plath by Anne Stevenson (which is not as good as Janet Malcolm’s book, The Silent Woman, although it is more extensive), there is an appendix that contains a nasty thing written by Dido Merwin called “Vessel of Wrath: A Memoir of Sylvia Plath”:

Dido Merwin lived in one of these beautiful houses at some point in her life. In the biography Bitter Fame: A Life Of Sylvia Plath by Anne Stevenson (which is not as good as Janet Malcolm’s book, The Silent Woman, although it is more extensive), there is an appendix that contains a nasty thing written by Dido Merwin called “Vessel of Wrath: A Memoir of Sylvia Plath”:

Sylvia Plath’s Boogers

I love you, Sylvia. I really do.

Hi. I mentioned this once in the comment section, but I’ll say it again: I dyed my hair red when I was fifteen and recited all of “Lady Lazarus” (click here to read it) in English class, which ends with, “Out of the ash/I rise with my red hair/ and I eat men like air.” I was really popular- dudes were lining up to get some action from me after I did that!(Click here to hear Syliva read it) ! I loved high school. Oh wait, that is a lie. Anyway, Sylvia Plath can also be funny, which I feel like highlighting due to the recent tragedy of her son’s suicide. Here she is, picking her nose: