There’s a new addition to my recent roundup of discussions about MFAs. Anis Shivani hates MFA programs. Or something. Sadly, the article reads more like the author is trying too hard to be… something. I found it difficult to take the writing seriously because it was so over the top. I love this response from Jason at The Barking. It’s something too. Who pissed in the Wheaties of everyone who loves to rail against MFA programs?

Mean Week is This Week What Does that Mean

Lynne Tillman Story

[The following is a story originally published in Bald Ego magazine, and will appear in Lynne Tillman’s forthcoming new story collection from Cursor in April 2011, titled Someday This Will Be Funny. The piece’s title comes from Clarence Thomas’s words in his testimony during the hearings, October 1991. Recently, Mr. Thomas’s wife allegedly left Anita Hill a voicemail asking for her apology. The story makes interesting use of popular media snafu as subject matter, which made me wonder more about what other great books and stories are able to incorporate such into their bodies in a fictional sense fluidly. Thoughts? – ed.]

Give Us Some Dirt

On long, summer nights in Pin Point, the Georgia air hung still as a corpse, and they’d wait for a breeze to save them. The heat felt like another skin on Clarence. His Mother would say, Clarence, what have you been up to? Playing by the river again? Oh Lord, we’ve got to clean you up for church, but aren’t you something to behold? And his mother would clap her palms together or spread her arms wide, like their preacher. Oh, Lord, she’d exclaim. Sometimes she’d point to sister and lovingly scold, “She doesn’t get up to trouble like you, son.” Clarence scrubbed the mud off until his knuckles nearly bled, while his sister giggled.

These days she wasn’t laughing so much.

The dirt couldn’t be washed away, not after Clarence kneeled in their white church, and they slimed him with derision. They couldn’t see who he was, how hard he’d worked, what he’d had to do, but he knew how to act. Behave yourself, boy, Daddy would say. Clarence’s grandfather, Clarence called him Daddy, was a strict, righteous man, who never complained, not even during segregation times, didn’t say a word, so Clarence wouldn’t, either. Those days were over, and they had their freedom now. He set Daddy’s bust on a shelf near his desk in his new office.

The D.C. nights mortified him, the air as suffocating as Pin Point’s. Clarence couldn’t free himself of history’s stench. On some interminable evenings, he nearly sent that woman a message, made the call, because she’d dragged him down for their delectation. He would pick up the receiver and put it down.

The noise of the ceiling fan assaulted him like a swarm of bugs. Clarence’s jaw locked, and his strong hands balled into fists. Every pornographic day of his trial, Clarence’s wife, Virginia, sat quietly behind him. She barely moved for hours on end, didn’t betray anything, and he worried that, if she had, the calumnies would have spread even further. The sniggers and whispers would have ripped her and him to pieces. He rubbed his face, recalling her startling composure. Rigid, at attention, a soldier in his beleaguered army.

He didn’t tell Virginia what the senators whispered — if he’d tried to marry her, if they’d had sex before the Court decided Loving v. Virginia, they’d have been arrested, and wasn’t it ironic — the Court made Clarence’s dick legal in Virginia, in Virginia? The Capitol’s dirty joke. Their dry Yankee lips cracked into bloodless grins.

The room’s high ceilings dwarfed him. Clarence glanced at a stack of legal papers. His wife was unassailable and white, but under their vicious spotlight her skin looked pasty and sick. She clung to him through his humiliation, even when disgrace lingered like the smell of shit. And now she bore the tainted mark with him.

Clarence wouldn’t say anything. He’d absorbed Daddy’s lessons, he could keep everything inside, all of it. He watched his grandfather’s bust, half expecting it to move, but it only stared down at him from the shelf. Clarence picked the receiver up again and put it down again. He was in that weird trance, and breathed in slowly, to calm himself, and breathed out slowly, to stay calm, and then closed his eyes. Clarence would leave that woman alone, leave her be, and, anyway, what was the sense, what was there to say years later, and there’d be consequences.

He was weary of scrubbing.

When he won, when the seat was his, he watched his friends’ joy, black and white, and they embraced him, slapped him on the back — remember what’s important, what it’s for, our principles, it’s all worth it. Clarence was the blackest supreme court justice in the land, the blackest this country would ever see. He knew that and held that inside him, too. Nothing and no one could whitewash that.

Clarence patted his round belly. He liked to joke about his heft, his gravitas, with his friends and the other Justices. When he delivered his rare speeches, he occasionally mentioned his girth, which drew a laugh, since his body was a source of mirth. Sometimes his hands rested on his stomach during sessions, when he was courtly if mute. The court watchers noted that he never asked questions, they remarked on it until they finally stopped. Clarence felt he didn’t have to say a word. He’d talk if he wanted, and he preferred not to.

When his hair turned white, like Clinton’s, that other fallen brother, Virginia said he looked distinguished, not old. Still, she worried about his weight, she didn’t want to lose him. He hushed her. He intended to be on the bench as long as he could, at least as long as Thurgood Marshall. He looked at Daddy again, eternally silenced, and sometimes talked to him, telling him almost everything. Clarence could hear Daddy, he could hear his voice always. He knew what he’d say.

Clarence’s trial bulged fat inside him. He’d never forget his ordeal, not a moment of it. He closed his briefcase and felt the urge to push Daddy from his perch. He would never let anyone forget his trial. Clarence chuckled suddenly, and a harsh, guttural noise escaped from him like a runaway slave. He’d have the last laugh, he was color blind, and they’d all pay in the end.

Lynne Tillman has published novels, story collections, and works of nonfiction. Her novel No Lease on Life was a New York Times Notable Book and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and she received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006. Her most recent novel is American Genius: A Comedy.

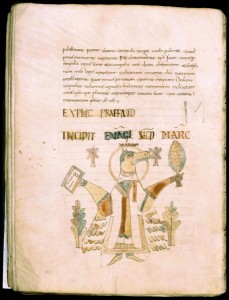

Harkness Gospels, Xanten Tanakh, Turkish Qur’an

The online portion of the New York Public Library’s Three Faiths exhibition includes images of the Harkness Gospels of Landevennec, Brittany, in Latin; the Xanten Tanakh of the Lower Rhineland, scribed by Joseph ben Kalonymus; and a fourteenth century Turkish Qur’an signed by Husam al-Faqir al-Mawlavi, disciple of Jalal al-Din Rumi. (Did I mention they’re all beautiful in a way books aren’t anymore?) Check out the photographic reproductions here.

The online portion of the New York Public Library’s Three Faiths exhibition includes images of the Harkness Gospels of Landevennec, Brittany, in Latin; the Xanten Tanakh of the Lower Rhineland, scribed by Joseph ben Kalonymus; and a fourteenth century Turkish Qur’an signed by Husam al-Faqir al-Mawlavi, disciple of Jalal al-Din Rumi. (Did I mention they’re all beautiful in a way books aren’t anymore?) Check out the photographic reproductions here.

What are the books you need to read between ages 17-22; if not then, never read them at all.

3 things I like a lot

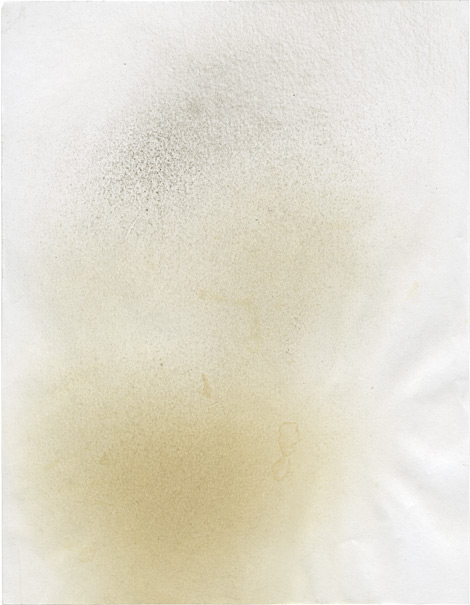

I.

"Echo #6," 8.5"×11", oil & dirt on paper, by JK Keller

Artist JK Keller does a “chronic drawing” of sorts, by replacing a mouse pad with a standard piece of office paper, the result of which is an apparition of presence and self. The dirty ghost of grime is our one untrained vocation, hands down.

I Like What The Hell Is Going On Over Here And Send Me Some Stuff

Open letter from Kenneth Goldsmith on UbuWeb about UbuWeb and why the wrong way is the right way to run a file archive of unprofitable products.

Fall is because Spring is colder than winter.

Forgot to say something about Thirty days as a Cuban in Harper’s. In to it. If you’re not a subscriber, go to the library or steal it from your doctor’s office. If they ask you why you’re hanging around the lobby, tell them you’re just making sure they’re here for you.

Taking submissions for hahaclever, including and especially ebooks ~10,000 words (like the highlander, there can be only one, what I’m saying is please try to be the highlander). Rebuilding the website, new comics editor coming on board, maybe a text editor, might have a board to come on, shit like that going on. If you’ve sent something in the past and haven’t heard from me, we’re sorry. They will get back to you soon.

At Titular, we could use a Halloween piece because I like when people send holiday pieces like Christmas’s Cocoon by Amber Sparks.

The Cardini Brothers’ Catch-Up has a new website for to look at with your eyes and a new print issue for to buy with your fingertips. The print issue is slick. It’s all comics and poems done in fun and done in love with making and thinking on the future and being ready for it to be happening or to be made to happen. This is a thing they did to promote the last, first issue. READ MORE >

The Muse of Impotence, The Muse of Impossibility

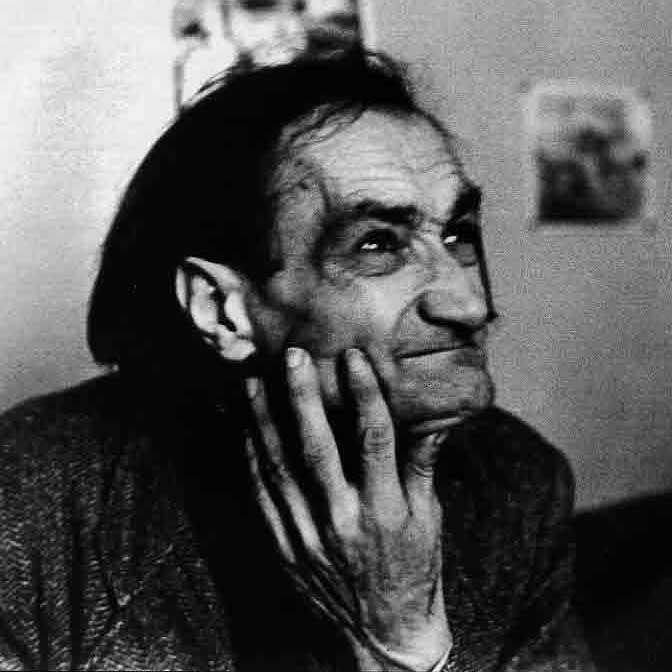

Alberto Manguel, badass

Read Alberto Manguel’s killer essay “The Muse of Impossibility” at Threepenny Review. An excerpt:

One day in December 1919, the twenty-year-old Jorge Luis Borges, during a short stay in Seville, wrote a letter, in French, to his friend Maurice Abramowicz in Geneva, in which, almost in passing, he confessed to Abramowicz contradictory feelings about his literary vocation: “Sometimes I think that it’s idiotic to have the ambition of being a more or less mediocre maker of phrases. But that is my destiny.”

As Borges was well aware even then, the history of literature is the history of this paradox. On the one hand, the deeply rooted intuition writers have that the world exists, in Mallarmé’s much-abused phrase, to result in a beautiful book (or, as Borges would have it, even a mediocre book), and, on the other hand, to know that the muse governing the enterprise is, as Mallarmé called her, the Muse of Impotence (or, to use a freer translation, the Muse of Impossibility). Mallarmé added later that all who have ever written anything, even those we call geniuses, have attempted this ultimate Book, the Book with a capital B. And all have failed. (Read more)