Mike Young’s All Good for Free

Dennis Cooper said (our own) Mike Young’s collection of poetry, We Are All Good if They Try Hard Enough, is an absolute stunner, and that even though they’re just great poems, he “can’t think of a paragraph anywhere that can match them for style or cover their emotional distance.”

Dennis Cooper said (our own) Mike Young’s collection of poetry, We Are All Good if They Try Hard Enough, is an absolute stunner, and that even though they’re just great poems, he “can’t think of a paragraph anywhere that can match them for style or cover their emotional distance.”

One element of the emotionality of Mike’s poems, which is evident from the funny but sincere video I’ve posted below the fold, is his interest in the way humans communicate and miscommunicate. The book’s epigraph is from Martin Buber, after all, and says, “When they sang of what they had thus named, they still meant You.”

I’ll be giving away three copies of Mike’s book. To win one, leave a comment below describing a miscommunication that was funny or ended up with a positive outcome, or just anything about a miscommunication. Mike and I will select three winners based on a complicated set of guidelines this Friday, so please make sure to leave a way I can get in touch with you.

“Please, sir, I want Pessoa.”

I was sick with flu and fever for a few days. In my state I hallucinated a tiny antique piano being fixed by a giant; his fingers were enormous pillows and he used them very delicately. The piano could be mine for fifty bucks. There was also a cartoon faucet that wouldn’t turn off. I wasn’t able to read or watch TV. When the grueling thing left my body, I sipped some mothermade gruel and convalesced not for the first time in The Book of Disquiet: READ MORE >

I was sick with flu and fever for a few days. In my state I hallucinated a tiny antique piano being fixed by a giant; his fingers were enormous pillows and he used them very delicately. The piano could be mine for fifty bucks. There was also a cartoon faucet that wouldn’t turn off. I wasn’t able to read or watch TV. When the grueling thing left my body, I sipped some mothermade gruel and convalesced not for the first time in The Book of Disquiet: READ MORE >

Tim Jones-Yelvington Short

Clean Babies

While we fucked, I’d hold his baby. To keep the baby off the dirt. Clean babies are happy. I’d hold the baby out in front, and he’d fuck me from behind. The baby never cried. The baby wandered. I mean its eyes. The baby appeared unfazed. I mean by the fucking.

We fucked in the park, in the tall grass. When my arms that held the baby bounced, the baby laughed and laughed. And while I got fucked, while I was holding the baby, I’d wonder about the baby’s other daddy. This was what I assumed, that the baby had another daddy, because unlike his first daddy, the daddy who fucked me, this baby was brown. I figured the baby was adopted. Something about the daddy, I could just tell, he seemed like the kind of man with a man at home. Even though he never talked about himself, he didn’t seem like he kept any secrets.

I wanted to ask him, Bring the other daddy to the park! One daddy to kneel on the ground and take me in his mouth. The other daddy to fuck me. And me to hold the baby. To keep the baby clean. But I never had the guts to ask.

That was a few years ago. That daddy disappeared. Now that park has fewer babies. Now those babies toddle. Oh man, those babies are getting big.

Tim Jones-Yelvington lives and writes in Chicago. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Another Chicago Magazine, Sleepingfish, Annalemma and others. His short fiction chapbook, “Evan’s House and the Other Boys who Live There,” is forthcoming in Spring 2011 in “They Could no Longer Contain Themselves,” a multi-author volume from Rose Metal Press. He is editing the October issue of Pank Magazine to feature Queer poetry and prose. He contributes to the group blog Big Other.

The title poem in Natalie Lyalin’s UDP chapbook, Try a Little Time Travel, is funny. It begins:

The title poem in Natalie Lyalin’s UDP chapbook, Try a Little Time Travel, is funny. It begins:

Try it a bit, instead of sexing

One night. Close your eyes,And think, Grandmother,

I’m coming to you, live!… (link to purchase)

I like capitalizing the first word in every line in poetry. Some people think it’s old fashioned. It doesn’t mean anything really, I just like it.

All the poems are good. Here’s a bit from another one, where the title is the same as the first line of the poem (a convention I also like, though not as much):

Jesus shows inside his flesh.

He is airy marbles and we are

All looking at his un-pain

Write a Book, Then Take a Picture of Yourself Looking Like a Douche and Put It Inside

Flavorwire has spoken out against the five major offenses frequently made in author photos. For my next book I want to take an author photo that breaks all five where I’m smoking while putting my hands to my face while twisting my torso to rest my arm on the couch in my office and supporting my head upon my fist.

My New Research Interest is Popular Literature

Contrary to what the critics tell us, popular fiction is not a swamp of barely literate escapism; popular fiction is composed of ancient myths newly reborn, telling and retelling a simple truth: ordinary people can do extraordinary things. Jack can plant a beanstalk that will provide endless food; a Tom Clancy character can successfully unravel a conspiracy that threatens the lives of millions. A knight can slay a dragon; a Stephen King character can defeat the massed forces of evil. Cinderella can attract the prince through her own innate decency rather than through family connections; a Nora Roberts heroine can, through her own strength, rise above a savagely unhappy past and bring happiness to herself and others.

—“Popular Fiction: Why We Read It, Why We Write It” by Ann Maxwell/Elizabeth Lowell

Zealot vs. Rattail

Apparently this is//all over//everywhere,

but I don’t have TV so I dunno nothing much.

The Ordinary Extraordinary: Three Gorgeous Books

I have enjoyed three really gorgeous books recently–Baby by Paula Bomer, The Physics of Imaginary Objects by Tina May Hall and Bad Marie by Marcy Dermansky. These are books you’re very much going to want to read because they are, simply, exceptional.

I love domestic stories. There is an intimacy to them that I find very pleasing because we’re allowed to see moments that are terribly personal. Everyday life is always the most interesting to the person living it but there are writers who can take everyday life and make it interesting for anyone. I have discussed, at length, my love for The Little House on the Prairie books and one of the things I loved most about each of those books was how everyday life was made interesting in ways that were always hypnotic. I loved the precise details about home and hearth, the food the Ingalls ate, the bitterness of the cold winters. In the hands of the right writer, a domestic story is more than just a domestic story. Another one of my favorite books is The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton, another story where the details of domestic life, elegant and refined, are conveyed meticulously. The ordinary becomes extraordinary as we read about the social and domestic mores of a different people in a different time.

September 17th, 2010 / 3:40 pm

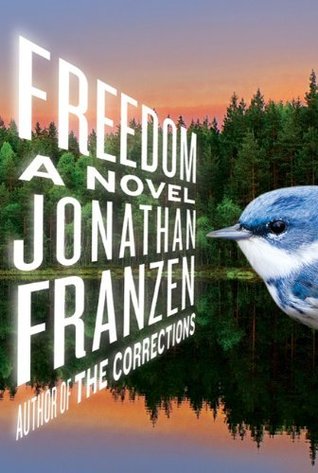

On Freedom

I have qualms about contributing to the current hype around Franzen’s Freedom, the endless pop-noise which ironically is confronted in the book’s lakeside allegory; but I feel compelled to, having been so moved by the book, and apologize for attaching my name to this review.

I have qualms about contributing to the current hype around Franzen’s Freedom, the endless pop-noise which ironically is confronted in the book’s lakeside allegory; but I feel compelled to, having been so moved by the book, and apologize for attaching my name to this review.

Soon after a quick intro written in omniscient third person, the reader encounters a longish part (broken into 3 chapters, labeled as such) written by one of its characters Patty — and yet, this doesn’t feel like “meta-fiction,” or even the show off flourishes of an adroit author; it seems, while not essential, strangely relevant. The reader’s context, for those who know Franzen, is that he is weary of “difficult” fiction for its preoccupation with language and fragmented narrative/consciousness (he wrote a Harper’s article critical of William Gaddis’ infuriating/challenging techniques, yet strangely aligns himself with D.F. Wallace, also an instigator). So one asks, why the difficult-ish structure?

September 17th, 2010 / 2:34 pm