Most editors really want your shit to be as awesome as you think it is

Ever go back and look at the things you wrote and submitted years ago and thought were great then and felt miffed or mad when they were rejected, and then realize with that time passed between, Hey, holy shit, this sucked, thank god nobody published this, I can’t believe I didn’t realize… ? So, maybe it’s not always the case, and maybe some editors’ tastes are too safe, or behind the curve, but maybe more often you could think of a rejection as a second chance, and say thanks for the protection.

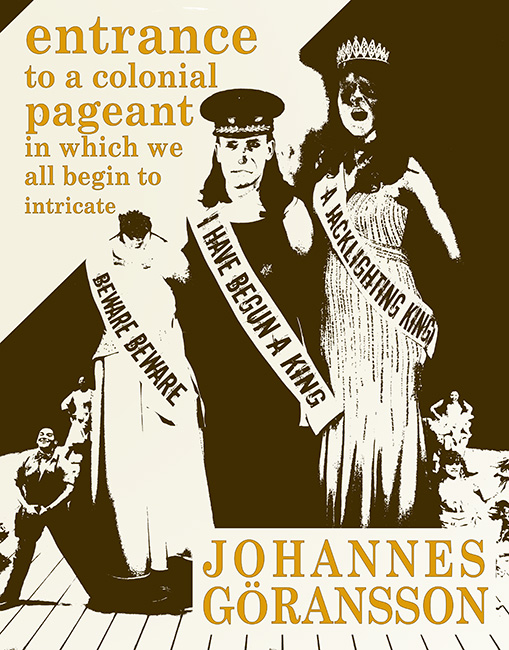

An Excerpt from Johannes Göransson’s Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate

An excerpt from Johannes Göransson’s forthcoming new book Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate is live at Tarpaulin Sky’s Chronic Content feature. I’ve read this book a few times this year already; it is insane sickly gorgeous power. It is a big thing. Preorder here.

Cohen, Julia. Triggermoon, Triggermoon. [2010]

“Julia Cohen’s poems will knock you out with their fresh logics like some moon-governed dream… this collection is half in the world and half in the ‘non-world’ that ‘occasionally rolls over you,’ utterly grounded in the domestic and wildly transformative.” —Elizabeth Willis

“The poetics enacted in Triggermoon Triggermoon is rare in its exuberance and delicate humanity, its wistful acceptance of imperfection as the human condition, imperfection as a kind of pet we grow to love and depend upon. I have grown to love and depend upon this book.”—Bin Ramke

77 interviews and now you people be happy goddamn you etc 14

5. Some MFA fuck will host the Oscars.

77. In other sad news:

14. Flash Fiction interviews Nicolle Elizabeth. I thank them.

My favorite part of it is that it isn’t getting another print run. Can I say that?

111. Kyle Hemmings interview at Dark Sky Magazine.

One of the biggest influences, besides other writers, was the nine or ten years I spent on the streets of New York, when I became addicted to the club scene.

1. Me here. My father brings novels to family reunions, funerals, and weddings. They are secreted in large pockets of his jacket. He brings them out, he reads them during the various proceedings. People have said things. But is this so wrong?

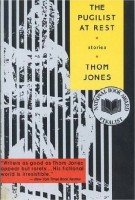

I Like It When Thom Jones’s First Person Narrators Break Into Essay in the Middle of a Short Story

Thirteen pages into “The Pugilist at Rest,” which is a twenty-three page story, which has up till now told a Vietnam War story, the first person narrator goes to white space, then returns with this:

Thirteen pages into “The Pugilist at Rest,” which is a twenty-three page story, which has up till now told a Vietnam War story, the first person narrator goes to white space, then returns with this:

“Theogenes was the greatest of gladiators. He was a boxer who served under the patronage of a cruel nobleman, a prince who took great delight in bloody spectacles. Although this was several hundred years before the times of those most enlightened of men Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, and well after the Minoans of Crete, it still remains a high point in the history of Western civilization and culture. It was the approximate time of Homer, the greatest poet who ever lived. Then, as now, violence, suffering, and the cheapness of life were the rule.” READ MORE >

{LMC}: On Gaythal Dethloff, Mother of Murder by Kellie Wells

Kellie Wells’s “Gaythal Dethloff, Mother of Murder” is a chatty story, in love with its own telling. Every description is exaggerated, dialogue is over-stuffed with podunky turns of phrase, actions are out of place but never really all that absurd. It’s like the costumer and the choreographer went to different schools. It’s a story that, while not always arresting, nonetheless lives and breathes with you if you let it. Like a puppet, it’s dead until you learn to move its strings and make it dance.

The story is essentially a monologue with witnesses. The first five hundred plus words are given over to describing the setting and the size of the characters. Before you’ve had a chance to forget, you’re reminded these are two of the tallest women in the world, and this is one of the fattest. There’s almost a kind of physical comedy in the constant repetition. By the time Gaythal tells how her good son, Nestor, became a serial killer, physical descriptions are largely unnecessary. As you read Gaythal’s monologue, you imagine it coming from the bed-ridden mouth of Jabba the Hutt. It feels like a bold move to front-load a story the way Wells does, to segment it so severely, but really it’s nothing new. Mark Twain’s tales are hinged in a similar fashion.

Nestor, once a great soup-kitchen chef, becomes a great murderer fulfilling his friend Ezekiel’s prophecy. Nestor kills and kills and kills. The murders, of course, come with a twist. Not a typical sicko, Nestor is doing his victims a favor. He kills Ezekiel to ratify him as a true prophet. He kills suicides so they can still get to heaven. Eventually, he ends up in jail.

Having given up her story, Gaythal shrinks in size. This all seems simple and straightfoward. We zoom back out of Gaythal’s monologue, back into our narrator’s thoughts, and, with her, feel a little let down. Gaythal’s had this bed-shaking, gospel-singing possession-like experience, but nothing really feels settled. Into the void of non-resolution comes a fun question: Are we dealing with ghosts? Is all of this more bizarre, more foreign than the initial description prepared us for? Without her brother’s love, the narrator is sure she’ll remain gigantic for eternity, but does she really mean eternity?

She says, “without being able to witness the faith of my one apostle ebb, I fear I am a lifer, Johnny-punchclock to the end of time. Without Obie, I am doomed to endless enormity. Without my brother’s love to engirdle me, I am an over-sized eidolon, hopeful opiate, just another reluctant cosmoplast roaming the backroads of the universe in search of the adoration of a sacrificial boy.”

Now, that’s hardly proof of ghosts, I know, but what does it mean?

Maybe a better question is why can’t I accept that maybe the narrator is just really sad she lost her brother, really alienated by her size, and desperate to find someone willing to worship her once more?

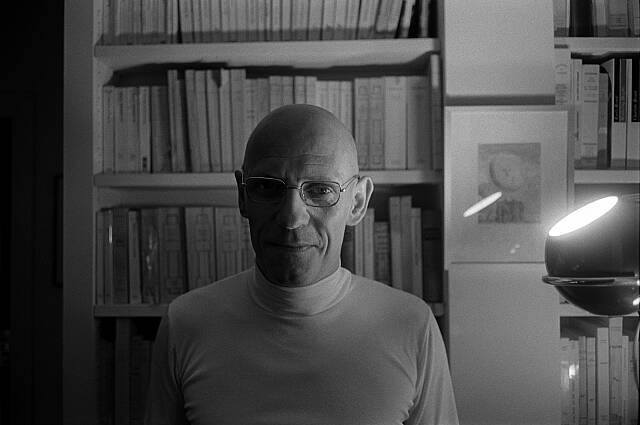

Power Quote: Foucault on Creation

“My desire is that a book, at least for the person who wrote it, should be nothing other than the sentences of which it is made; that it should not be doubled by that first simulacrum of itself which is a preface, whose intention is to lay down the law for all the simulacra which are to be formed in the future on its basis. My desire is that this object-event, almost imperceptible among so many others, should recopy, fragment, repeat, simulate and replicate itself, and finally disappear without the person who happened to produce it ever being able to claim the right to be its master, and impose what he wished to say, or say what he wanted it to be. In short, my desire is that a book should not create of its own accord that status of text to which teaching and criticism will all too probably reduce it, but that it should have the easy confidence to present itself as discourse: as both battle and weapon, strategy and shock, struggle and trophy or wound, conjuncture and vestige, strange meeting and repeatable scene.”

[from the preface to the 1972 edition of History of Madness]