Tree of Nowledge

Odd how the leaf in Apple’s logo nicely plugs up the bite, as if it were ashamed of its mark. The empty arc, short of being a design curve, may point to the consumerist endless hunger for Now. The prophetic bible story “Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil” is of course misogynist, as the anonymous authors (talk about a raw deal; imagine the royalty checks) made Eve the dumb broad who fucked humanity over until eternity, and all for a lousy apple. (For a Faustian contract, consider at least a filet mignon.) The serpent, I suppose, is brand marketing — western idol worship without all the hairy rules. Yin and Yang is the Taoist assertion that equal yet contrary forces, while seemingly antagonistic, are not only connected, but mutually dependent on each other. Drop the good and evil and throw in Yin and Yang; without judgment, we’d all be in a better place. May our revised Apple logo be a kind of iYin and iYang of the iChing. iOnce tried to meditate, per the advice of my then therapist, and fell so deep into the Holism that every atom in my buttocks buzzed, as if slipping through the universe’s sieve. It was my phone on vibrate.

Odd how the leaf in Apple’s logo nicely plugs up the bite, as if it were ashamed of its mark. The empty arc, short of being a design curve, may point to the consumerist endless hunger for Now. The prophetic bible story “Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil” is of course misogynist, as the anonymous authors (talk about a raw deal; imagine the royalty checks) made Eve the dumb broad who fucked humanity over until eternity, and all for a lousy apple. (For a Faustian contract, consider at least a filet mignon.) The serpent, I suppose, is brand marketing — western idol worship without all the hairy rules. Yin and Yang is the Taoist assertion that equal yet contrary forces, while seemingly antagonistic, are not only connected, but mutually dependent on each other. Drop the good and evil and throw in Yin and Yang; without judgment, we’d all be in a better place. May our revised Apple logo be a kind of iYin and iYang of the iChing. iOnce tried to meditate, per the advice of my then therapist, and fell so deep into the Holism that every atom in my buttocks buzzed, as if slipping through the universe’s sieve. It was my phone on vibrate.

Miró Killer Joke Peaks Open Low

1. At Burnaway, an Atlanta arts blog, I’m curating a new column of “writers on art,” which today features Heather Christle on Joan Miró: “I wanted secrets, and I wanted to laugh, so I snipped letters from my head and sorted them by shapes: those which slant, those which curve, those which face left or face right.”

2. At Thought Catalog, Christian Lorentzen writes a long screed for the nonexistence of hipsters, with reasoning including that our generation has never had a good serial killer.

3. At The New York Times, Joshua Cohen turns in a take down on the brand new 1,000 page book from McSweeney’s, Adam Levin’s The Instructions, calling it “a very long joke.” Other readers: yay, nay?

4. At Montevidayo, Johannes Göransson writes about the “ambient violence” of Twin Peaks.

5. Submissions to New York Tyrant are now open.

6. I forgot about this great old music video from Low:

A Conversation With Charles Dodd White

Charles Dodd White is author of the novel Lambs of Men and co-editor of the contemporary Appalachian short story anthology Degrees of Elevation. His short fiction has appeared in The Collagist, Fugue, Night Train, North Carolina Literary Review, PANK, Word Riot and several others. He teaches English at South College in Asheville, North Carolina. He has an old rescue mutt that sheds a sweater’s worth of hair each day. His home page is www.charlesdoddwhite.com. We had a fantastic e-mail conversation about Appalachian writing, his novel, and much much more.

Roxane: What are some of the challenges of writing historical fiction? What are some of the pleasures of writing historical fiction? What kind of research did you do for Lambs of Men?

Charles: The funny thing about historical fiction is that I’m not exactly sure what it is. How old does something have to be to meet that definition? Some contemporary novels have a strangely historical feel, something say like Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, while other stories set thousands of years in the past, like Vollmann’s The Ice-Shirt, are eerily contemporary. I didn’t set out to write something that was consciously trying to perform a certain type of literature. I set the story in the past, specifically in the period shortly after the First World War because I wanted to write a story on the edge of time, a situation aware of a kind of eschatology, and for me WWI with its stark, nightmarish images was the most natural choice. I was also interested in writing a book that was essentially a primitive story, a fabular treatment of the real cost of violence, and I needed an earlier century for the verisimilitude. I’ll admit too, I take a comfort in a world without cell phones. It calms me.

Like one of the main characters, I was a Marine, and much of what I wrote about was from previous knowledge of Marine Corps history. I also have spent a hell of a lot of time in the woods with guns, so I guess you could say a lot of the research was pretty much first hand.

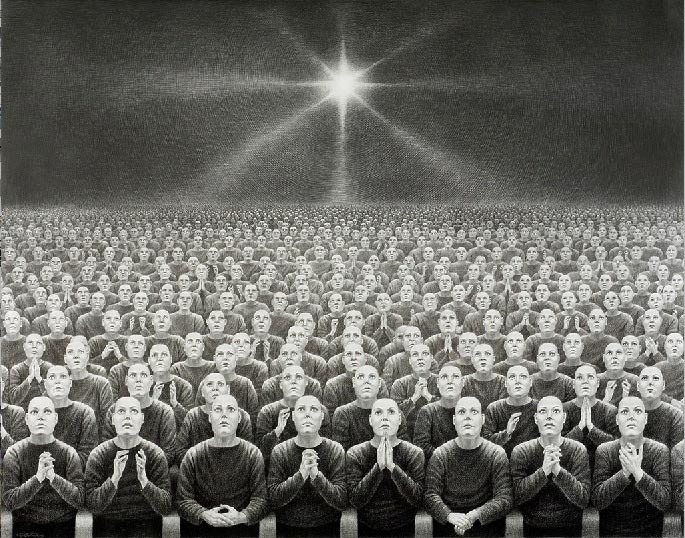

Untitled Sunday Evening

If Plato’s Allegory of the Cave gives us shadows on the wall, the residual simulacra of light as farce of being, then Allegory of the Popcorn may be light’s emanation into the butter-scented theater, the one-sided cube of the silver screen into which we go dumping our dreams. Or, this Allegory of the Retina, light’s retarded power point presentation in the mind, one redundant slide at a time, our wavering arms in front of us grasping at the punctured sack of the outside world, the world we share.

A Socratic question is an arrogant passive-aggressive one; didactic, with presumptive maturity, an ostensible “instructive” question. For example, mother asks me when was the last time I washed the sheets, an answer which in a couple of months can be described in years. “One year Ma, lay off me”; and so her nightmare of bed bugs laying eggs is hatched in her mind. The last Socratic question I asked was this morning: wtf I said to the brand new day. Philosophically, we all live in Greece.

Christian Hawkey’s Ventrakl

New from Ugly Duckling Presse, Christian Hawkey’s Ventrakl is a “work of collaboration” between the author and Georg Trakl, who died in 1914, 55 years before Hawkey was born. The book, then, is collaborative in the sense that Hawkey uses Trakl’s language, presence through language, image, presence through image, legacy, and other ghostly traces to interact with his corpus and his poems to create a new kind of relationship of exploration. What results is a hybrid catalog of poises, pictures, and entrances that entwine the two bodies and the bodies of languages of the two men in powerful and often surprising ways.

November 7th, 2010 / 2:34 pm

Check out “In Room 208” by Stephen Collins, which won the 2010 Observer/Cape graphic short story prize. It’s creepy and lovely. A couple whose honeymoon is cut short by bad weather retreat to a hotel, where a strange inertia takes hold…

Differences, casually.

Maybe the primary makings of and differences between art and entertainment are this: art is more intensive, and entertainment more extensive. That the properties of art that seem powerful are harder to measure, harder to define or classify. That entertainment is more obviously calculated, patterned. And that, if you feel you have to, you can measure both properties and use whichever name you want.

ZSNYRB

Zadie Smith writes with mixed feelings and a note of condescension in the New York Review of Books about The Social Network, a movie I saw four times in the theater. (Enough times to know that she misquotes the dialogue.) From the opening scene it’s clear that this is a movie about 2.0 people made by 1.0 people, she writes, and it does its job so well that it feels more delightful than it probably, objectively, is. Mercifully she ignores the tedious controversy over the film’s alleged misogyny in favor of a nuanced analysis of its generational significance. Remember half a decade ago, when you’d meet someone and one of you would say, “Are you on Facebook?”