My Experience Writing for Muumuu House

Wrote about Tao Lin for Hobart.

Exchanged emails with Tao about what I wrote.

Tao cut and pasted part I’d written about Zac Zellers and Marie Calloway and wrote beneath it “this seems funny to me.”

Replied with a paragraph in which I described Zac Zellers as the “Where’s Waldo” of Ann Arbor.

19 mins later got email from Tao saying “you should write something about this and send it to me.”

Flags and Fists

On December 19 1984, Daniel Larusso defeated Cobra Kai α-male John “Johnny” Lawrence in the final match of the All Valley Karate Championships using the “Crane,” a kick derived from a Zen-like balance within, best practiced on a stump. One wonders if sweeping Daniel’s leg didn’t simply clear the floors to his enlightenment. The tournament’s logo, likely a creation of the film’s set designer, is a fist from the POV of an imminent victim. Turn it 90° on its side, and you have a quick allusion to a fist-pumping “wax on/wax off” Daniel likely practiced in his bed every night with quixotic visions of Ali (Elizabeth Shue). The film’s real muse, however, is transcendental absorption — to catch a fly in chopsticks not with one’s eyes, but knowing. All this faux-Buddhism, despite the slightly racist exoticism, is a wonderful thing. Daniel’s shower curtain costume on that fateful night may be a metaphor for evasion, conceived by Mr. Miyagi who himself had been hiding from troubles back in Okinawa. The red dot in the flag of Japan represents the sun, though its derivative in the flag of Bangladesh symbolizes the blood shed in gaining independence from Pakistan. “If a white flag means surrender, a black flag represents anarchy,” says Raymond Pettibon, co-founder and designer of Black Flag’s logo, which I always considered a fist with a tucked-in thumb. Unlike Karate, which employs offensive strikes, Jujutsu (literally, “the art of yielding”) is a grappling martial art in which an opponent’s force — both as vector and psychological intent — is used against himself. Daniel would have simply gotten out of the way, a John Cagean absence splattered by boos. As a flying fist gives you something to run from, anarchy may give a kid something to run to. I turn up “Rise Above” at work, but am only able to relate to …it’s no use, never mind the preceding try to stop us, but… A true cynic will not believe in punk (only what his hypochondria tells him). Henry Rollins staunchly stands on stage with taut legs hunched in some martial stance, as if bracing himself for the unknown. There is a moment of dread when a mosh pit begins to form around you. Someone hit my face and my glasses flew off. I got on my hands and knees, desperately grasping for re-vision, a halo of flailing arms above me and boots so near my fingers but never quite touching. It’s like I disappeared.

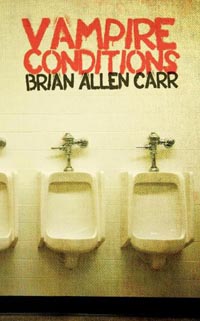

Vampire Conditions

Vampire Conditions

Vampire Conditions

by Brian Allen Carr

Holler Presents, 2012

114 Pages / $9.99 Buy from Amazon or Powells

When given the choice, I mostly choose not to read literary realist fiction. I’ve been out of school for more than a year now, so I’m accustomed to having the choice. I read Brian Allen Carr’s collection Vampire Conditions anyway, and I loved it. I knew that I wanted to review the book, too, which meant that I would have to find a way to articulate why I loved it. There are two keys. First, Carr takes nothing for granted. Second, he never justifies his stories.

Carr’s refusal to take anything for granted makes him different from most writers of literary realist fiction because most of these other writers — the ones I now choose not to read — will resort to writing what they think “it’s really like” when they aren’t sure what to do next. That is to say that they often make boring events and characters (affairs and the middle-aged people who have them, unconsummated affairs and the middle-aged people who don’t have them, cancer deaths and the survivors who mourn them, suicides and the people who commit them, drugs and the people who use them) and congratulate themselves for writing the world the way it is. This takes the reader for granted because it assumes his or her interest will sustain itself without the writer’s help. This takes the world for granted because it suggests that the way we expect things to be is the way they are. Such writing fails as an imitation of reality; nothing in this life is ever much like what it’s “really like.”

I don’t believe that Brian Allen Carr writes his literary realist stories by asking himself what is likely or real. If he were doing it that way, he wouldn’t have made up Thick Bob, a grotesque who one day gave a bartender so much shit she actually tased him — and who, when he saw how much pleasure it brought the bar’s other patrons to see him tased and collapsed on the floor, proceeded not only to continue antagonizing the bartender, so that she would regularly repeat that performance, but to mount brief shows on a small stage inside the bar, wherein said bartender hits him with a bat, explodes fireworks in his clothes, throws darts at his person, and etc. If Brian Allen Carr wrote stories by asking himself what is likely, he wouldn’t have invented the protagonist of “Lucy Standing Naked,” a young boy of Asian descent, adopted by white Texans, who is named Nelson, and who is learning to play the guitar, and who sings country music better than most white boys, and who is in any case a novelty because there’s never been a famous country singer who looked like him. He wrote Nelson because Nelson was interesting. He wrote Nelson because Nelson makes a good yarn.

January 4th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

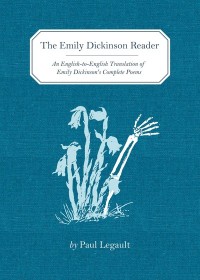

25 Points: The Emily Dickinson Reader

The Emily Dickinson Reader: An English-to-English Translation of Emily Dickinson’s Complete Poems

The Emily Dickinson Reader: An English-to-English Translation of Emily Dickinson’s Complete Poems

by Paul Legault

McSweeney’s, 2012

247 pages / $17.00 buy from McSweeney’s

[Note: In the text that follows, the leading number refers to the catalog number assigned to each Dickinson poem and its accompanying translation. These numbers are derived from the Franklin (1999) edition of Dickinson’s oeuvre. The trailing trailing number appearing in square brackets references the actual “point number”, and thus the in order in which the reviewer would prefer, although would not require, that these 25 points be read. JM]

12. Concurrent with my reading of Legualt, I’ve been following Brandon Brown @ Harriet (the blog) on translation. How he says, “There is no master.” I feels it applies here, too. But maybe Brown and Legault are colleagues, correspondents, even. (One of them, surely, is wren-like and sherry-eyed.) Or the inventions are independent identicals, like Darwin and that other guy*. I imagine Brown and Legault meeting in some profile coastal city with a very specifically desirably demographic profile, dotted with saloons and taverns, meeting over craft beers intensely hoppy and a shared literary ambivalence which tastes of salt without being salty per se. But this meeting, which is like a prelude to a deeper or longer encounter, this meeting wordless, sudsy… these beers, these refreshments bitter and compulsory… the possibility of Brown and Legault merely overlapping at the bar is as far as my imagination goes. And is this stopping heartful, braked by the anxiety of influence? “Emily Dickinson wrote in a language all her own, thus the need for this English version of what she meant.” (7) Wait, so does the agony of influence deny the mortification of the flesh? [3]

29. Handed over to the hand that writes, “simple” and “direct” are always driven forward. I mean, forward as out or away, into that exile that enable observation, not into the completed future of conveyance. (That, and I just don’t trust McSweeney’s.) [4]

98. Biography bugs me most of all. I wish we had no daguerrotypes of Dickinson to caption. I wish reading really pressed some sort of pause button on life itself. I wish I didn’t feel like I, too, know how caretaking will warp you. [16]

167. But with such rueful wishing, if not in it, a realization disappoints me with surprise and surprises me with disappointment: I have this idea all the time. [25]

221. Translation isn’t telling, much less re-telling. But it snags in the same temporal flow as does narrative. [7]

319. What was Dickinson herself translating? Emerson? Swedenborg? Whiteness: “racial,” temperamental, existential (not a word she would have recognized, not for all the tenements in Amherst)? The Puritanism that idles with such delightful perversity in Frost’s “The Generations of Men”? The erotics of a universal chlorosis? Proverbs she found when she dreamed of communion in the hills so misty from her gnomic lookout? Hell, that’s it. Dickinson, even her doubts are too bold. For all Legault’s contemporary light shines, it can’t cast her shadows. [8]

333. Not that I think Dickinson’s—or any poet’s poetry, for that matter—is inviolable. Reading it will always rough it up anyway. But what about introversion? [2]

392. Consider Paul Legault’s project a sort-of ekphrasis on Dickinson’s unwritten autobiography. Consider that Dickinson’s medium isn’t poetry, that Legault’s isn’t comedy (though more than a few of these read as if they could have been spouted by a vintage, arrow-through-the-head Steve Martin), that there is no translation evident here, only notation, only commentary, only adumbration, thoughts broken in the process of their own manufacture by the machine that is, quite literally is, addiction to the author’s held-out promise of exegesis. Consider your prurient self covertly mocked. [21]

421. Emily Dickinson isn’t your friend, and never was. Anyway, friendship thrives on novels (its parasitic), not poems. And Emily Dickinson does care, in the sense that she wants to know something true of her own being. That she would exemplar herself, if only privately. [20]

438. The apostrophe of the second-guess. The syntax of the spit-take. After all, the literal is the absurd. [13] READ MORE >

January 3rd, 2013 / 12:09 pm

Mark Baumer tried to get funds on Kickstarter to write 50 books in one year. It didn’t get funded. He’s writing them anyway and releasing them one at a time. You can read them online and you can buy them. I love Mark Baumer.

George Anderson: Notes for a Love Song in Imperial Time by Peter Dimock

George Anderson: Notes for a Love Song in Imperial Time

George Anderson: Notes for a Love Song in Imperial Time

by Peter Dimock

Dalkey Archive Press, Forthcoming February 5, 2013

158 pages / $11.20 Preorder from Dalkey Archive

In 1998 Dalkey Archive Press published a slender volume with the title A Short Rhetoric for Leaving the Family. This novel joined the list of new fiction at Dalkey that has quietly developed a reputation for publishing works of significant literary value rather than commercial prospects. Indeed, when the late John Leonard reviewed the novel in The Nation, he commented that it had been brought out “almost secretly,” words that surely disconcerted Dalkey’s publisher John O’Brien whose promotional budget must be infinitesimal when compared to that of Random House or HarperCollins.

A Short Rhetoric for Leaving the Family was the first novel by Peter Dimock, a highly respected editor in New York who was at the time working as editor and director of academic marketing for Random House. Dimock is a veteran of Sonny Mehta’s regime at Random and a long-time friend and associate of Toni Morrison, whom he accompanied to Stockholm in 1993, but Dimock is still otherwise unknown beyond a small circle within New York’s literary establishment.

These days Dimock is working as a freelance developmental book editor and as editor of an online journal on the social implications of contemporary finance titled Rethinking Capitalism. (The journal attempts to foster communication between academics and financial professionals on the social creation of value and the market culture of global finance.) This is a far cry from Dimock’s origins as a student of American History and his own literary inheritance as the son of the classical scholar George Dimock, Jr. who, in the 1950’s, published an article in The Hudson Review titled “The Name of Odysseus” that had a wide impact upon Homeric and literary scholars.

Looking back after a dozen years at Dimock’s first work of fiction, those who read it can still marvel at the uniqueness of the book. The novel purports to be a letter from the disgraced son of a powerful American family (a son whose sanity and capacity to live without supervision have been questioned) to two nephews during their childhood and promising the distribution of substantial monies when each reaches his majority. The narrator’s father has been a principal architect of the Vietnam War, and the narrator, Jarlath Lanham, resisted that war by the means his class and privileged upbringing afforded him. Jarlath’s older brother, out of loyalty to his father, served in combat in Vietnam and has returned with unaddressed psychological trauma.

January 2nd, 2013 / 12:00 pm