Ali Liebegott Obsessed

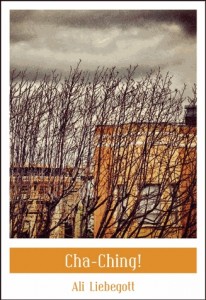

Cha-Ching!

Cha-Ching!

by Ali Liebegott

City Lights / Sister Spit, 2013

252 pages / $15.95 Buy from City Lights or Amazon

I was furious with Ali Liebegott for writing a novel. We’d lost another poet to the tyranny of fiction. But really, we gained Ali’s careful witness to luck, desperation, and desire, now turned to the queer project of making a world.

Gaines and losses are perhaps apt metaphors for Cha-Ching!, Liebegott’s latest work, in which gambling figures as a central theme. But for Theo, its main character, gambling is about more than fortunes. Gambling is a currency of hope.

Fuck reviewers citing “universal” concerns that appeal to “general” audiences. This character is a self-made, self-secure “sirma’amsir,” and an appealing one. Always on the brink. Of going broke, of drinking again, of saying the wrong thing to the right lover.

Cha-Ching! is an addiction story without recourse to self-help and redemption. It’s a romance built not from exchanging vows, but traumas, drugs, and fluids. You had me at the puke on my sheets. The characters are always making something out of nothing—a dime into a jackpot, a shitty apartment into a home, a blank sky into a declaration of love. It’s gruesome. It’s hilarious. It’d make a puppet out of the hardest of hearts.

I caught Liebegott in the middle of her Sister Spit tour to ask her about her many obsessions. When her tourmates weren’t asking her for keys to the van she was driving, this is what happened:

TJR: If you had the choice to make out with Dostoyevsky or Van Gogh, who would you pick?

AL: I think Van Gogh, but that might be ageist, because I think I’ve only ever seen portraits of Dostoyevsky as a balding man. Van Gogh had really bed teeth, right? I think Van Gogh, although they both seem like terrible problematic relationships, so either would do. It’s tough. But probably Van Gogh.

May 10th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Soderbergh on Cinema is Soderbergh on Publishing

Film director Steven Soderbergh recently spoke at the 56th annual San Francisco International Film Festival. Before the speech Soderbergh said he would “drop some grenades.” Rarely does that happen. But what Soderbergh did was special – he pierced holes into an industry that is corporatizing and mainstreaming a once beautiful and individualistic art form.

I’m not a student of film nor would I consider myself knowledgeable on the industry. So after I read the full transcript of Soderbergh’s speech I wondered why I was so captivated. The answer was simple: I was reading a speech about the state of film, but as a writer, I was reading a speech about the state of publishing.

Soderbergh’s main sticking points: a bigger film budget yields bigger results, those in charge at the studios don’t watch cinema, artists need to be supported financially long term, ambiguity is toxic to a mainstream audience, and too much emphasis is placed on testing and pre-sales numbers, may sound like sour grapes to some, but I believe he’s accurate. I believe what he says about the state of cinema is in direct correlation to how I, and many, feel about the state of publishing.

Soderbergh loves strangeness and ambiguity in film. The ambiguity in my second novel, published by Penguin, was questioned by my editor. The push to extend the “reality storyline” in the book became a main focus during revisions. There had to be more of a love story. Things had to make sense. Sentences deemed strange and vague were questioned with “I really like this, but what does it mean?” The push for things to “make sense” has resulted in boring movies and boring books. READ MORE >

Baby Adolf’s Summary of the 5th Annual CUNY Chapbook Festival

A couple of days ago Baby Adolf, the first Bambi Muse baby despot, and I met up at a McDonald’s near a Germanic bakery located somewhere on the Upper East Side.

My outfit featured, among other things, sunnies. As for Baby Adolf, his deck was brown.

Both Baby Adolf and I ordered vanilla ice cream cones. And after we ordered second vanilla ice cream cones, Baby Adolf screamed (unlike PhD’s, &c, no one at Bambi Muse is captivated by “conversation”) about how he wanted to be on HTML Giant quite badly. After all, Baby George III has been and so has Baby Marie-Antoinette. Why should the boy who will one day kill six million you-know-whos and five million other oh-who-cares be denied the chance to appear on the site run by the continually cute-looking Blake Butler?

“Maybe,” I said to Baby Adolf, at the McDonald’s near the Germanic bakery on the Upper East Side, “if you gave me three Baby Ruths, four Jujubes, and a Coca-Cola then I’ll publish your summary of the 5th-annual CUNY chapbook festival on 9 May 2013.”

Baby Adolf grumbled his assent. What follows is Baby Adolf’s summary:

***

On Saturday Baby Adolf, accompanied by his mommy, Klara Hitler, visited the 5th annual chapbook festival at CUNY. For some time, Baby Adolf believed CUNY was just another way to say NYU. After Saturday, though, Baby Adolf realized that they were two separate entities. NYU is a big ugly college that’s usurping the West Village, while CUNY is a big ugly building in Midtown.

The festival took place in a plain white hallway, and, according to Baby Adolf’s eyes, there wasn’t anything particular festive going on. There weren’t any military marches or bellicose speeches prophesying global war along with the resurrection of the fatherland. Unfortunately, there were too many boys who looked like they’d just blown in from Bedford as well as a fair amount of girls whose clothes suggested that they had just come here from their weekly Park Slope Lesbian Separatist meeting.

But some commendable creatures were present, like Baby Ji Yoon. She spent most of her time at the festival taking mysterious notes, as if she were spying for a certain country that starts with North and ends in Korea.

May 9th, 2013 / 3:02 pm

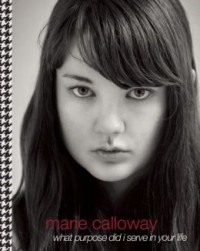

25 Points: what purpose did i serve in your life

what purpose did i serve in your life

what purpose did i serve in your life

by Marie Calloway

Tyrant Books, 2013

200 pages / $19.00 buy from Amazon or SPD

1. The film The Hurt Locker opens with the quote “The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug.”

2. Marie Calloway’s novel what purpose did i serve in your life opens with the quote “We teach children not to go into stranger’s houses, so why do it as an adult?”

3. The film The Hurt Locker is divided into a number of distinct scenes showcasing Sergeant First Class William James’ deactivating various bombs in intense, maverick ways. The viewer is left with the post-suspense of the diffusal, the slowing of blood-pressure lets one reflect on war as the hazmat is removed.

4. Marie Calloway’s what purpose did i serve in your life is divided into a number of distinct reflections each culminating in some kind of sex which she somehow coordinates in an often intense, maverick-y way. When being degraded, she posits that she deserves it. She states she feels relief and confusion in making herself an object.

5. The movie The Hurt Locker portrays James’ fearlessness in the face of danger and ends with his inability to escape the very thing that is destroying him.

6. Marie Calloway’s novel portrays a young woman moving through life after vaguely mentioned past traumas. She is a rape victim and this shapes her sexual actions and reactions. Though often being grossed-out or averse to a range of sexual suggestions (from being eaten-out to force-fed her own vomit) Calloway’s actions are that of a compliant, non-confrontational lover.

7. In 2011, Gawker called Marie ‘just a girl, with a Tumblr’.

8. In the Jeremy Lin chapter of the book, Lin points out:

“If someone says your writing has flaws or is good, that implies they know a concrete goal that your writing has, which can be measured in numbers, and that the number would be higher or lower if you changed your writing in a certain way, I feel, by that seems incredibly hard to measure, even if two different people had agreed upon a purpose for your writing that could be measured, like ‘increases heart rate in reader’ or something. But it can be depressing to never think in terms of ‘good’/’bad’ without defining contexts/goals in each instance.”

9. A staff member of the Paris Review once told William S. Burroughs that sex seems frequently equated with death in his writing. Burroughs responded:

“That is an extension of the idea of sex as a biologic weapon. I feel that sex, like practically every other human manifestation, has been degraded for control purposes, or really for antihuman purposes. This whole Puritanism. How are we ever going to find out anything about sex scientifically, when a priori the subject cannot even be investigated? It can’t even be thought about or written about. That was one of the interesting things about Reich. He was one of the few people who ever tried to investigate sex—sexual phenomena, from a scientific point of view. There’s this prurience and this fear of sex. We know nothing about sex. What is it? Why is it pleasurable? What is pleasure? Relief from tension? Well, possibly.”

10 a. “If you like me, you have to like shyness.”

b. “I’m smart at some things but not with people or at growing up.” READ MORE >

May 9th, 2013 / 12:26 pm

“I get so very tired of having to talk about literature. I didn’t begin writing because I wanted to sit in a room and discuss the subjectivity in Wordsworth and Ashbery; I began writing because I had made friends with the dead: they had written to me, in their books, about life on earth and I wanted to write back and say yes, house, bridge, river, hair, no, maybe, never, forever.” — Mary Ruefle (via Amber Sparks)

OUT OF NOTHING #[0]; Or, blurbing the whole cacophony

[out of nothing] #0: theoretical perspectives on the substance preceding [nothing]

[out of nothing] #0: theoretical perspectives on the substance preceding [nothing]

Ed. [out of nothing], October 2012

144 pages / $12 Buy from Amazon or Createspace

When the opportunity presented itself to review the printed edition of [out of nothing] recently, I jumped on it quicker than anything I’ve jumped on since I was ten. The idea in my mind wasn’t even necessarily to “review” OON but just to be able to hold the thing in my hands, first and foremost. [out of nothing] and Lies/Isle are obsessions of mine of late—the online versions, that is; these strange permutations of art and thought and science and everything intellectually captivating you could imagine organized into endless mazes of online content. If we’re to believe in such a thing as collaborative arts on the internet, this, in my opinion, is the sort of thing heading up the effort.

So anyway, I immediately requested a review copy of [out of nothing] and when it reached my house I felt connected to something likely akin to movements in the art scenes of New York in the 70s and 80s or Berkeley and various Western lands in the 60s. Here was the personification of serious writing and art in the twenty-first century and here was my opportunity to consider it. To be sure, considering it is likely the greatest feat I’ll here be able to accomplish. I’ve tried over the past few months to conceive of items to potentially submit to a publication like OON and I can’t for the life of me make it happen. Perhaps it has something to do with the collaborative nature of the thing, perhaps the three editors and founders of OON are just that-fucking-savvy that they’ve managed to push the intellectual envelope even more, I’m not sure. All I know is, if The New Yorker was once taken (dreadfully) seriously as a hub to receive one’s culture, [out of nothing] (both the print and online version) is its strange twenty-first century cousin doing bizarre rituals/experiments in the city’s basement trying to reanimate the corpse of Soren Kierkegaard.

But I digress:

Considering the structure of this anthology, I’m going to move through and evaluate each piece in order with as calculated a response as I can muster. This being an anthology of the highest order, my efforts as critic of OON will be best if the responding structure of my own writing not attempt the strange collective genius inherent to that which I’m writing about. I featured the subtitle “blurbing the whole cacophony” to draw comparisons with Melissa Broder’s piece “blurbing every story in the new New York Tyrant,” because it’s helpful to have something to riff off of this time of year, when the mind slows down and wants only to recoil into hours of sleep. O sleep.

(Furthermore, given the array of materials that exists within the 144 pages of OON, the length and style of my interpretations will vary, and where my words will surely fail to illustrate the images/texts and their substance, I’ll include scanned images of pages because I’m not beyond that and I love this fucking thing too much to assume to understand it.)

Now, regarding the introduction:

IS THAT ALL THERE IS?

by Jon Wagner

Reading this, I’m reminded of something Rick Roderick says in his lecture regarding the works of thinkers like Foucault, or Habermas—and one could easily expand this to Deleuze, or even Derrida if one was so inclined—whose works can hardly be called “philosophy,” in the traditional sense. He goes on to emphasize that contemporary “thinkers,” must encapsulate more of society than was previously expected of philosophy, and that the greats like Foucault or Nietzsche must be acknowledged as something else to be understood. Not only can Wagner’s introduction not be called an “introduction,” in the strict understanding of the word, but it belongs alongside the works of those aforementioned thinkers as something transcending mere criticism, philosophy, history, geneology, ontology; the list goes on. What’s given here is first a consideration of the idea of [nothing],’ and what the bracketing of the word/idea itself might mean, then an introduction to the proceeding texts is given and it’s briefly explained that commentary will be provided by a handful of “Jabberwocks,” along the way—“Benjamin, Baudrillard, Derrida, and Kierkegaard. This is something I’ve not seen done, like, ever, and in addition to creating this extremely fun intertextual environment while reading, it brings to mind all kinds of questions about the apocryphal, marginalia in general, and ghosts. My own thoughts here channel and mimic Deleuze, Pasolini, and Miss Peggy Lee within a restricted economy of expression that bleeds a general excess in the very effort of constriction.” I.E. OON does not seek to be a mere anthology, nor even a mere physical book, and will go so far as to resurrect the dead in texts to bury its collective mind in the concepts of nothingness as deeply as possible. This is unlike anything dubbing itself an anthology that I’ve yet experienced, and onward we must go.

PRE-WAR

Nicholas Grider

I’ve wondered a great deal lately about the idea of a text somehow avoiding the idea of a start and finish entirely, and bridging the gap towards something more diffuse. One thinks of Joyce in this regard and Finnegan’s Wake, or perhaps something more contemporary like Lost Highway, but even still these things do have a beginning as far as location is concerned (the “first” page, the “opening” of the film). I’d feel safe in positing that Grider’s piece comes close to achieving this rather timeless sensation. Although the writing only runs across three pages, the blend here of Walter Benjamin’s and Jean Baudrillard’s insights with the author’s own do lend an eerie, spectral air to the thing and that tied with the fractured indentation of Grider’s lines tempted me to read the thing out of order, forwards and backwards; as many ways as I could considering its brevity. I won’t begin to argue that we’re a great deal closer to printed texts that could actually be called diffuse in this regard, but this first in the anthology does seem to chip away at this idea. I’ll include here the interplay between Grider and Baudrillard, without question my favorite moment in the piece.

“or you have better things to do, you are a background character who laughs a little too long at the funeral parlor with 2.5 walls, you can do a lot of things with flashcuts these days, jackknifing, binge drinking, shoplifting, heavy breathing. {}

{Indeed, you can, when the reified even it so much so that a single marker can indicate an

entire conceptual package: an action, a life, an historical trajectory. JB}”

READ MORE >

May 8th, 2013 / 11:00 am

25 Points: Solip

Solip

Solip

by Ken Baumann

Tyrant Books, 2013

200 pages / $14.95 buy from Amazon or SPD

1. Solip isn’t a novel.

2. If you’re looking for plot, look elsewhere.

3. This might be the single most difficult book to write jacket copy for.

4. This isn’t experimental literature for the sake of experimenting.

5. The book is physically tiny and the front cover is minimalist.

6. There is nothing on the back cover. A wall of black staring at you. No pull quotes or blurbs, and by the second page you realize why: because the book speaks for itself.

7. I read this tiny book in one sitting in a coffee shop amazed by its power and had to go indoors to drown out the outside world to reread it and devour it properly.

8. Baumann’s writing demands your attention. It’s as if he’s bottled up the intensity present in much of online fiction and spread it out over a longer narrative, not losing a beat in the process.

9. The sentences are divine. The language will cast shadows. They will hum to you. Listen closely.

10. The book has a pulse to it, a pulse that beats louder and more pervasively as the text unfolds. READ MORE >

May 7th, 2013 / 3:01 pm

The End of San Francisco

The End of San Francisco

The End of San Francisco

By Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore

City Lights, March 2013

192 pages / $15.95 Buy from City Lights or Amazon

When I left Seattle and went to grad school in Los Angeles at the end of the 1990’s, I read Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities and it changed my life. It gave me a framework to understand the searing misunderstandings going on in the feminist self-defense collective I had been pouring my heart and soul into since we came together in response to the rape and murder of our friend Mia Zapata. Some of us in the collective became best friends while others of us could barely speak to each other without spitting. Sisterhood was powerful but it was also alienating. Any unified identity as a community, the word we used to describe who we were and who we felt accountable to, was absolutely imagined.

Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities is kind of an odd place to start a review of Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s new book, The End of San Francisco, since she is an antidote to rather than perpetrator of sterile inaccessible academic writing. But The End of San Francisco is as much social critique about the impossibility of collective dreams as it is a memoir looking back at queer and feminist community building in the ‘90’s. And it feels life changing reading this book in the midst of the marriage debates.

The book moves in and out of time and geography, traveling in a non-linear journey across several U.S. cities including Seattle and, of course, San Francisco. This journey is a timely reminder that creating a queer family once meant we were running away from the families that rejected us, that broke our hearts, sometime our bones, and often our will to live. It’s a story for all of us who ran as far as we could to find the other freaks searching for new ways of being family and being in relationships that were more than our parents’ misery. This is a story about those of us who gave a shit about health care, survival and telling our stories, not getting married or getting tax breaks.

There is no distance between memory and remembering in the writing. It’s all happening at once. As a reader I felt like I was inside my own memories while I was given access to the formative moments of someone else’s life. I kept wanting Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore to be sitting next to me so I could say, “Right, me too.”

Right, me too.

Right, becoming aware of not being phased by the violence as a form of self-protection. I know that one well.

May 6th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Animated Gifs as Cinema

I was planning to put up the next installment in my experimental fiction series today (part 1, part 2), but school has interfered. (I’m writing a paper on Dickens’s use of the narrative present in Great Expectations, plus grading 40-something research papers written in response to Hanna Rosin’s The End of Men: And the Rise of Women.)

In the off chance that you’d like to read something new by me, I recently published an article at the film site Press Play, “Are Animated Gifs a Type of Cinema?” Since then, Landon Palmer has responded with an article at Film School Rejects (“Animated Gifs are Cinematic, But They’re Much More Than Cinema“), as has Wm. Ferguson at the 6th Floor, the New York Times Magazine‘s blog (“On the Aesthetics of the Animated GIF“). I’m planning a follow-up post as well as an interview with Eric Fleischauer and Jason Lazarus, the directors of the gif anthology film twohundredfiftysixcolors, whose premiere I managed to catch a few weeks back. And the Press Play article is itself a follow-up to two articles I posted at Big Other in early 2011: “How Many Cinemas Are There?” and “Why Do You Need So Many Cinemas?”

I’m only just beginning my studies on the gif, so I appreciate any and all feedback.