Interview with Angela Leroux-Lindsey of The Adirondack Review

I’ve always been curious about the darkroom where literary magazines come together. This is a series of interviews engaging, talking, and sometimes annoying editors about their magazines. How did they come about, what do they hate about editing, and what do they love most about it? This is the first in the series and I talked with Angela Leroux-Lindsey of The Adirondack Review. The visual imagery is simply stunning. The Adirondack Review is like an art gallery curated online, constantly evolving, fused together with great stories, poetry, and essays. In preparation for the interview, I pretty much went through the entire archives and got a brain dump, Matrix-style, in art and photography. A jolt to the system is what I like feeling with my lit magazines and reading directly from their about page: “The Adirondack Review is an independent online quarterly magazine of literature and the arts dedicated to publishing poetry, fiction, artwork, and photography, as well as interviews, articles, book reviews, and translations. Recently named a ‘great online literary magazine’ by Esquire and a ‘top online journal’ by The Huffington Post, TAR was established in the spring of 2000, with its first issue appearing that summer.”

As a brief bio and introduction to Angela Leroux-Lindsey:

Angela Leroux-Lindsey is editor of The Adirondack Review and senior editor with Black Lawrence Press. She writes for Kirkus Reviews and A&U Magazine, and has contributed essays and stories to phys.org, Animal Farm, Innovation Magazine, NY Metro, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and others. She lives in Brooklyn.

***

PTL: Can you tell us about the review, how did The Adirondack Review first get its inception and how did you first get involved?

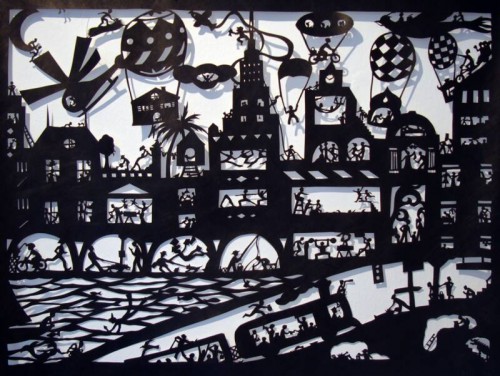

Angela Leroux-Lindsey: The magazine has actually been around since the summer of 2000—the founder editor, Colleen Ryor, was sort of a pioneer in never going to print, which is something I’ve always admired. But I didn’t start contributing until 2006 or 2007. At that point Diane Goettel was editing, and when she left to run Black Lawrence Press full-time, I took over. So my first issue was in the winter of 2009. A big part of the appeal was their early commitment to publishing art. I especially love how being online gives us the freedom to publish as much full-color art as we want; in the fall issue, I featured almost 30 images by five different artists and photographers. This is something we could never afford if we had to pay for ink and paper. We also publish poetry, fiction, and works in translation in every issue, a mix of mediums that I think is really lovely. Every time we close I’m sort of delighted to see unexpected threads emerge that tie completely different submissions together: a drawing that evokes the tension of post-apocalyptic familial relationships next to a story that takes place on a placid lake over the course of an afternoon but is really about survival. Discovering these entanglements and bringing so many different people together is so much fun. It’s the best job.

PTL: Each issue is packed with fiction, poetry, and some of the most incredible photography and art I’ve seen. What goes into the curating and selection process?

ALL: Well, like every small lit mag out there, I rely so much on my staff. We all volunteer, which makes it even more amazing that I’ve found a group of people willing to be so thoughtful and imaginative about how we compose issues. Nick Samaras, our poetry editor, came on board when I did and he’s brilliant. Google him, read his poetry, you’ll just swoon over it.

Regarding art, some of it comes in through the submission process, but a lot of it I solicit. Sometimes I’m just scrolling through tumblr and come across a piece that floors me. And I’m always completely thrilled when a big name that I’ve solicited says yes: I mean, Manfred Mohr was on the cover of the summer issue. I was watching some of his animated videos from the 70s on YouTube, and figured I’d send him an email to ask if he’d be interested in featuring some of his new stuff. And he emailed me back within a week and said yes. I’m still excited every time this happens. It’s magical. Richard Mosse is another example. I’m in love with his INFRA series, which is online now.

Really, getting to work with all of these artists and writers is absolutely the best part of having this role. Not just meeting new people and developing friendships—like with you, Peter—which I really value. But living in Brooklyn and getting to hang out with so many writers I admire is killer. You wouldn’t believe the people I’ve met and fallen completely to pieces in front of. I hosted a reading once with Paul Muldoon and could hardly pronounce my own name when I introduced myself. And then to watch emerging writers and artists who have published work with us go on to publish books or exhibit work at major galleries or museums is really awesome. My friend Kit Frick has a completely gorgeous chapbook coming out called Echo, Echo, Light from Slope Editions. We published early versions of a few of these poems in 2011 and I can’t wait to see how they’re incorporated into a collection. And Luba Lukova, a political artist whose work I sought out for the cover of the first issue I edited, will show at MoMA next month. Revisiting these issues and experiencing that kind of folding of time is a cool thing. It makes me think of the larger view of independent publishing as a sort of performance art space in itself.

Here’s this interesting thing about some people who sent letters to the editors of Vanity Fair and People. (I remember reading one of them very clearly: the Michelle Price one on VF.)

DO YOU USUALLY READ ‘LETTERS TO THE EDITOR?’ DO YOU EVER WRITE THEM?

…….I am Paulina……

Lying in bed the other day and listening to Paulina Rubio’s sultry and filthy voice I felt suddenly (no, I knew!) that I could have written her songs and that she could have written my poems.

——Encrusted W/ Emeralds——Stinking Ditched——Boiling——

——I’m On The Back——Of An Elephant READ MORE >

September 24th, 2013 / 10:36 pm

“It’s time to kill the idea that Amazon is killing independent bookstores.”

This post is rather thin on evidence to claim it’s killing anything, but — while I am mostly agnostic on Amazon’s effects — it is undeniable that Amazon has made reading a much easier habit for many people, and I suspect this leads to more reading in general, not only more reading through Amazon.

A Close Reading of a Poem By a Girl

While being educated upon literature, one of the most marvelous assignments I received was to conduct a close reading of a poem of my choosing. Though 99 percent of the people who associate themselves with literature nowadays probably perceive poems as mere documents that they’re coerced to comment upon in workshop, I am mesmerized by beatific poems, and I believe each one necessitates thoughtful evaluation. After all, when you see a beautiful look by, say, Calvin Klein, you shouldn’t just mumble “Nice job, Calvin” and then zip right along to the next one — that’s inconsideration. What everyone should do is concentrate on the look exclusively in order to notice the particular shade of grey and the way in which the squiggly white stripes contrast those of the grey ones.

The same should be so for a poem.

The poem I selected to do my close reading with was Charles Churchill’s night. An 18-century poet who didn’t like gay people, Charles is often ignored, while poets like putrid pragmatist Alexander Pope are emphasized. But, really, Charles needs ten times the heed of Alexander, as Charles is ten times as terrific as Alexander.

For Charles, the greater public views the daytime as the place of hardworking humans and the nighttime as the space of a sordid species. But in his poem, Night, Charles says that daytime is much more foul than nighttime. Using heroic couplets, Charles explains why the daytime is contemptuous, calling its denizens “slaves to business, bodies without soul.” In contrast to the spiritless stupids, those who wander in the night have an “active mind” and enjoy “a humble, happier state.” Near the end Charles states, “What calls us guilty, cannot make us so.” While I concur with Charles that just because the 99 percent say it’s true doesn’t make it true, I don’t agree that the nighttime is so wonderful, as gay people go out at night a ton, and gay people aren’t a thinking bunch.

But Charles’s poem is still bold, bellicose, and abrasive, and all of those traits are laudatory, and, through my close reading, I became much better acquainted with them.

Also disseminating a decided amount of close reading are the baby despots of Bambi Muse. Baby Adolf did one on Emily’s “Presentiment,” Baby Marie-Antoinette did one about Edna’s “Second Fig,” and Baby Joseph did one concerning William’s [“so much depends”].

Close readings appear to be very vogue. So, having already summed up a close reading of a boy poet, I will presently present a close reading of a girl poet.

September 24th, 2013 / 1:29 pm

An Open Letter to Readers and Writers on the Internet Regarding the Founding of El Aleph Press

Dear Internet Readers,

You know that boringly recurrent conversation in which someone laments the end of print and someone else talks about how craftsmanship, design, and embracing new media can actually make small presses more viable and exciting than ever? In that conversation you are the second (more optimistic) person. Or at least you like to hold out hope that that person’s correct. And because of that you really should know about El Aleph Press.

In the interest full disclosure and as proof that I know what I’m talking about, I should say that I’ve known and been friends with El Aleph’s founder/editor, Michael Bagwell, for several years. I like him, I trust his aesthetic. So naturally I was excited to hear that he’d started a press. Then I actually got my hands on the things he was doing and got even more excited. El Aleph makes books, broadsides, t-shirts, and now an anthology. Their website features writing, of course, but also short films and, soon, a whole host of other multimedia work. They’re getting involved in a lot of projects across a range of media, and everything they touch is beautiful and careful and medium-specific.

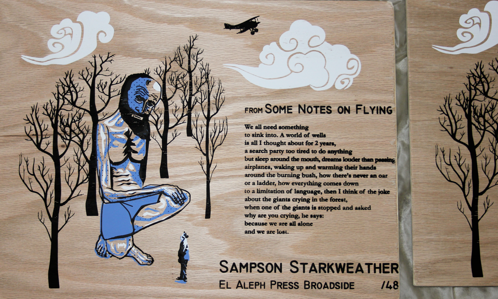

Let me give two examples of the work El Aleph is putting out. Their first broadside features a short Sampson Starkweather poem with a color illustration printed gorgeously onto solid wood. Their first book, Or Else They are Trees, is a collaboration between Bagwell and the artist Rebecca Miller. It’s similarly gorgeous, a mix of poems and full-color artwork. If there’s an early hallmark of El Aleph’s work it’s that language and design are equally meticulous.

I should also mention that El Aleph is currently looking for submissions for their forthcoming anthology. From what they’ve published and what I know of Bagwell’s aesthetic, you’d be well served to send in formally adventurous works, lyrical weirdness, and texts that are equally surreal and sincere. You should also send reviews, comics and more traditional stories/poems.

All of the information on El Aleph, their projects, and submissions guidelines are available at their website. So check out/submit/support, etc.

Very Best,

Ben

September 24th, 2013 / 11:00 am

2013 NATIONAL BOOK AWARD LONGLIST (REVISED EDITION)

You heard the 2013 National Book Award longlists came out last week, I presume.

Perhaps you noticed the dearth of small press titles, and the ubiquity of familiar names and themes?

For what it’s worth, I begrudge none of the recipients their nomination. In all sincerity, I’m sure they’re fine books. But honestly I wouldn’t know. I’ve read zero of them. Not a single book in any of the categories. And excluding the YA category, since I know little to nothing about that genre, I’m really only interested in reading six of the thirty selected. For the most part, the official selections just don’t represent the type of material I would choose to spend my limited time reading.

That said, I see no reason to denigrate the official list. I do, however, see plenty of reasons to offer a different list of praiseworthy books that deserve more attention. So, I offer this revision in the spirit of the mission statement of the N.B.A.: “to celebrate the best of American literature, to expand its audience, and to enhance the cultural value of great writing in America.” Hopefully this might encourage others to expand the scope even farther by creating their own revised longlists.

To compose my revised longlist of National Book Award nominations I first need to deterritorialize the genre categories, because many of the works I think deserve this recognition resist easy categorization as “fiction,” “poetry,” or “nonfiction.”

Next, I will constrain myself to those books written by non-HTMLGIANT contributors, because it would probably seem too nepotistic to include them.

As well, I’ll constrain myself to books that privilege text over image, which means I’ll exclude a bunch of rad comics that could easily make my list. And I’ll exclude “scholarly” texts, despite there being a fuckload of good ones this year.

And finally, I’ll select thirteen books, because the official judges selected ten in each of the three categories and I’d rather there only be one category and I’d rather it be odd rather than even in number.

Now then, in alphabetical order of author’s last names, my selections for the 2013 National Books Award Longlist:

“We met at AWP. Can I email you my short stories?” 30 Awkward Moments From Your Creative Writing MFA. Yep.

“Narrative Gold” — (In the Memoir Swamp) — Talking to Seattle’s Elissa Washuta

*****

*****

Rauan: why is most Memoir so bad, so boring (and in so many instances just a kind of “grief porn”)??

Elissa: Memoir is the genre most often entered by celebrities. It’s also full of books by people whose lives have been stricken by remarkable tragedies or circumstances that are marketable to readers hungry to know about other people’s lives. If we want to know about that secret wig that Andre Agassi wore for years during his tennis career, he’ll gladly sell us a copy of his memoir, Open. If we want to know how Dustin Diamond felt about playing Screech, he’ll give us an earful in Behind the Bell. Politicians use memoir to push their agendas; the infamous use it to set the record straight. Many celebrity memoirs are ghostwritten, and I get the feeling that the people on the covers don’t think much about craft.

Memoir isn’t working, I think, when the author has no ear for language, no eye for image, a limp voice, and an insistence upon a narrative arc that delivers an easy revelatory triumph at the end. In mediocre-at-best memoirs, the narrators balk when faced with the opportunity to tease out the most complicated tangles of their experience–sometimes, the revelation of their own complicity in what’s gnawing at them. That’s narrative gold in memoir: reading about a character with agency is much more compelling than reading about a helpless victim. I certainly do not wish to judge or take away from the lived experiences of the people who wrote the memoirs that I’ve found the most to critique in (including Prozac Nation by Elizabeth Wurtzel and Lucky by Alice Sebold), but in memoir, there’s a problematic tendency to close the gap between art and life that allows the most exciting work to take place.

I read and listen to (audiobooks of) lots of memoirs. I’ll listen to any memoir that Seattle Public Library has available. While I do think the memoir genre is full of duds, I’ve read so many thrilling, vibrant, well-written memoirs in the past few years, including Rat Girl by Kristen Hersh, The Guardians by Sarah Manguso, Confessions of a Latter-Day Virgin by Nicole Hardy, READ MORE >