Sunday Service: Sasha Fletcher

WE DON’T HAVE ALL NIGHT

Above us is the moon. It is huge in the sky

and it is bearing down on us

as though

there was no tomorrow

because tomorrow there will be nothing but the moon

up in the sky and looming

all ominous and heavy and bright

and that is just fine with us. Listen.

We could use a sense of menace around here.

We could use a call to action Or a house

Or a barrier. A magical barrier.

like a fence. We could use a fence.

****

Why a fence you ask?

Because of reasons, which are as follows:

demarcations, unwanted elements,

property values, taxes, building codes,

civic duty, creepiness, and bears. Dear bears

we built these fences for a reason. Dear reasons

we do not care. Sincerely, the bears. The bears

have learned to compose letters

and nobody cares. Dear food let us eat you

Dear ocean full of menace let us eat you

Dear terrifying ocean full of menace we mean it

Dear wolves we have already eaten you and now we sit here

by the ocean wearing your torn-off faces like masks

until the ocean full of menace gets the picture. Dear ocean

full of menace

we are right here. Under the moon. We are waiting.

****

The Anxiety of Influenza

“All bad poetry is sincere,” I got that from Harold Bloom, who got that from Oscar Wilde, who got that from his clever self, which hardly means that “all great poetry is insincere,” which again I’m getting from The Anxiety of Influence (1973), not the actual book but from Amazon’s virtual “look inside” feature, its animation, estimation, or interpretation of reading less affectionate than reading itself; that is, with a book, whose every page one holds the corner of, and hears going by, one by one, like shuffling a deck of cards in the slowest way possible. Bloom’s point is evident in his title, that the history of literature is ripping off others in the quest to be original; how this is both logically impossible yet always manifesting, albeit inadvertently through our “misreading” of the original. It is true when I let my subscription to The New Yorker expire, months later, at the magazine rack, I solemnly wonder about what I’m missing. I feel the same way passing bars at night, the brittle tinkering of glasses as a high-hat over the cacophonous rumble of voices. Like the red marker a teacher uses to point out what is wrong, the red squiggle of spellcheck is a kind of incision into the flesh of intention, if you were a half-blind James Joyce typing Finnegans Wake. More ominous is the green one, citing sentence fragments you didn’t know were fragmented. “Ignore all,” one may apply to grammar, dentist appointment reminders, and their social life. After watching The Road (2009), I told myself that a few weeks before the end of the world — faithful that Fox News or a crazy person would alert me — I would simply buy a can opener. As people ate each other, I’d have clam chowder and lychees. I didn’t read the book; that this is still considered blasphemy is redeeming: we still believe in the higher collaboration between sole words and imagination. Jonathan Franzen admits to buying copies of his books to give as presents to friends. At the register, he feels like he’s buying a Penthouse. “No, it’s not for my own use…” he says, or at least says he would say, I mean this is the problem with quoting a quote, to which the double quote shielding a single quote offers itself as a solution, like a large circle containing a smaller one — a bagel around a cup of coffee, inside a gurgling stomach — or a ventriloquist with his hand up someone. Everything that is wireless eventually concedes to a cord. Battery is not a crime. Nor is the stomach flu really influenza; it’s gastroenteritis, which hardly needs you to go viral. A man shot another man in Russia over an argument about Kant (the gun must have been a manual). Exactly how sour is cream cheese supposed to be? A man publishes a blog post in America and quickly walks to the bathroom. He has that not so refresh feeling all day. This was entirely made up.

How many literary institutions spam you weekly, or even many times a week? And which? And for what?

I Am Ready To Die A Violent Death by Heiko Julien

I Am Ready To Die A Violent Death

I Am Ready To Die A Violent Death

by Heiko Julien

Civil Coping Mechanisms, Nov 2013

Book Page at CCM

In I Am Ready To Die A Violent Death, Heiko Julien presents to us a kaleidoscope of images, ranging from the suburban, to pop culture references, memes, and the internet, presented through a meditative narrator questioning everything they see, while at the same time doubting what they are saying. Ironically the writing is both positive and self-deprecating at the same time, mirroring the multi-faceted life we inhabit online through different personas; we are both the nice, tolerant and compassionate person, and we also want to die a violent death, alone, so we can feel something that is real in a physical sense, not just through social networking.

What strikes me first of is that these pieces began as either self-published e-books, Tweets, or Facebook posts. This way of sharing ‘content’ online seems to be central to ‘Alt lit.’ Heiko has already begun a dialogue with his audience before the book has been published; I had read most of these pieces online before coming to read this book. This is quite a unique trend that is happening in the publishing world; there isn’t one way of ‘being a writer.’ And the idea of publishing itself has become quite flexible. I feel that Heiko is aware of this, and the writing in this collection reflects the continued dialogue he has with the Alt Lit community, which he seems to be a major part of.

“Facebook is the void that talks back.” (facebook post)

Heiko is well aware of the power of memes, in a similar way Steve Roggenbuck talks about the memeplex, which he defines as “a grouping of associated memes that are consistent and which support each other.” And that a “meme” is a unit of culture and/or anything that is spread by imitation (stylistic moves included). Heiko also uses the language of memes to project this view; via different forms of online language, be it advertising, tweets, Facebook, or blog posts.

I am afraid of men but I am a smart boy so i intellectualize my fear in the form of Cool Shaming and Tight Blaming. If I’m being honest, I would like to be the Number One Dude. I admire strong guys. I like to watch them play sports. I relate to the idea of a Buff Bro. I like a dude so top heavy I can topple him with a good push. I like to push dudes into pools in the summertime.

For Heiko, as well as others in the online community, memes also constructed through online ‘brands’ or ‘personas’, where ones identity becomes a meme. This feels like one of the central themes to not just Heiko’s writing, but to the ‘genre’ of Alt Lit. What makes Alt Lit a unique genre, however, is that it feeds into the aspects of an online community members and environment which Heiko references a lot in his writing, and the online community all construct different personas, or identities, through different social media outlets. In this way, Heikos writing puts a mirror up not just to himself, but the community he responds to. The writing does not just reflect the community that is Alt Lit, however, it also stems from something else, something more ‘human,’ or ‘natural‘, whatever that may mean in the ‘internet age‘ that we all live in. Social stereotypes become crystalized through online media, which in turn become memes, and a part of the online language that Heiko channels in his pieces.

But I guess what I most want is to be in actual love with a woman who actually loves me back until we die painless, unexpected deaths simultaneously, but someone told me this was already done in a Bad Movie.

There is a strong sense of irony in these pieces, that the only meaningful things that can be said have already been said through media, and that is all the narrator knows. Memes have become our ‘language,’ our way of communicating in our ‘environment,’ and these pieces show the point of where a meme stops and the human being typing them begins. The writing is a projection of the narrator’s own inner dialogue, while at the same time being mixed in with memes and other online jokes. In this way, we are constantly reminded that there is a person behind the writing, a person who has their own desires, goals, and emotions.

and we are dancing

like we know people

Out There

want to take our money

and kill us

and we still think they are beautiful

Notice how “Out There” has been capitalized, this “other” could possibly mean something like a world free from online content, something more ’real’, but the narrator, by calling it the other, has no idea what this could be. In doing so, we are shown a crisis the narrator is having, and one that we are all aware of; all we are becoming aware of is our online presence, then what is our ‘real’ identity?

You can see a lot of Rare Vids of Young Dudes hanging out at home and doing funny voices if you search Just Chillin on YouTube. Go ahead and try this and maybe then you will learn how to love without needing to receive anything in return.

November 8th, 2013 / 11:00 am

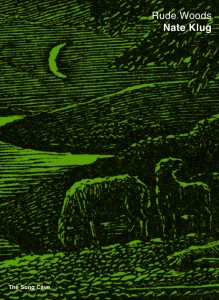

To Overdose on Clover: A Review of Nate Klug’s Rude Woods

Rude Woods

Rude Woods

by Nate Klug

The Song Cave, 2013

76 pages / $17.95 Buy from The Song Cave or SPD

In his Deformation Zone, Johannes Goransson writes of the nature of translation saying in the process of rewriting a text “the ‘meaning’ may have been ‘lost’ but the materiality of the text is brought to life.” Nate Klug, in his latest book Rude Woods (The Song Cave, 2013), embodies this type of translation at its most intriguing and productive. Eschewing the constraints of a strictly “faithful” translation in favor of a more multifaceted dialogue with Virgil’s Eclogues, Klug himself becomes one of the lyrical shepherds he invokes as he responds to the Eclogues which are themselves, he writes, “poems about responding—listening, picking out, and answering back the pleasures of song.” Klug’s brief examination of each of Virgil’s original ten eclogues offers a contemporary take on the pastoral tradition that brings to life both Virgil’s lyric refinement and dynamic content.

Most refreshingly, these are not your mamma’s frilly little nature poems. The pastoral as an idyllic scene is revealed as artifice; in its place the earth as complex, fraught, psychic landscape is shaped. Here, Virgil-via-Klug becomes a sensual experience in the most dynamic way as it invites readers into physical observation of and participation in the environment while invoking, as W.R. Johnson states in the forward, a “severe concentration on emotion [that] determines these poems’ unique form.” Take a moment to experience the following lines:

from “A Hymn to Prophecy” (from Eclogue IV):

“wool will never have to dye: for the rams / will trick their fleeces, from boiled-saffron-yellow / to the deep purple produced by shellfish juice.”

or from “Against Epic” (from Eclogue VI):

“even this young orb called earth, / spinning dry, hardening, until things slowly / owned their own forms.”

or, lastly, from “Two Longer Love-Songs” (from Eclogue VIII):

“I saw you once and was lost. / Something wrong and warm carried me off.”

What we get here are emotion-driven images, but they are not grounded in the typical poetic gesture “I emote therefore my poems have gravity.” Instead, they are vivified by the transformative power of sensual detail. Not only are “wool” and the “earth” and the “you” brought to life for us as readers through the uniqueness of their portrayal, but the portrayal itself is metamorphosing—”Right there in the field, grazing lambs will go red” (from “A Hymn to Prophecy”).

But I must admit initial skepticism. A moment of strong lyricism will get my attention but often for the wrong reasons. The lyric, as many writers and readers know, has a tendency to overindulge. An emotive, senses-based series of poems about love and loss and shepherds singing in a flowery pasture could be a hotbed of disastrous pitfalls. But what Klug does well is interrogate these tropes and traditions even as his words participate in them. He creates tension by restraint—not through expected thematic or plot-drive narratives but through the imagistic and sonic qualities of the language itself.

In his translator’s note, Klug refers to this quality as “the rough music I sought”; it is “rough”—and “rude” and bitter and bruised. It is also imbued with a “sweetness” and beauty that, in moments, startles with its clarity of vision. It is this complex “song” that ushers forth the unexpected, “unnatural” environment of the new pastoral, a landscape that becomes less of a tangible place of sheep and shepherds, and more of a conceptual space in which sensual experience serves as the landscape itself.

Rude Woods does at times feel burdened by these heavy underpinnings. The overarching structure of emotional registers spoken through sensual detail may feel exhausted by the end of the text. Yet Klug makes brilliant self-referential moves to address the process of finding balance in these lines. On the whole, he takes his own advice (via Virgil) to maintain a fascinating lightness, an ethereal quality, that he writes of in “Against Epic”:

“A shepherd should keep the flock fat but his lines refined, like exquisite thread.“

There is indeed a threadlike fragility to these poems; there is also, to continue this metaphor, a strength in how tightly woven the poems are through their imagistic and sonic complexity. Though there are moments when the translation may feel too heavy handed, Johnson is right when he notes, “most translations of the Eclogues attempt to reflect the original’s intricate language with some variety of high style. . . Klug has devised a conversational idiom that relies on spare diction and spare syntax, on a pure clarity of sight and sound to give us superb poems that give Virgil’s pure lyricism a genuine ‘answering form.'”

By the close of the text, we have been privy to a complex and dynamic series of contemporary translations that pay homage to Virgil’s intentions while reaching interestingly beyond the bounds of the tradition from which they arise. As the prophet-poet rightly tells us in “A Hymn of Prophecy”:

“It’s here, the beginning, or the end of everything, / as the Sibyll has sung; time for the great order / to start over . . . the insurgence of a new kind of human being.”

***

Jessica Comola is an MFA candidate at the University of Mississippi where she serves as poetry editor for the Yalobusha Review. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Anti-, Redivider, and Everyday Genius, among others.

November 8th, 2013 / 11:00 am

POEM-A-DAY from THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN LUNATICS (#3)

The Penis List

Jim Behrle was recently featured in “Kill List” as a comfortable poet. It’s possible that he is the least famous poet to earn such a distinction. He lives in Jersey City, NJ. By day he wears a green t-shirt and a nametag at a university bookstore, fetching textbooks for people with bright futures. He lives his broken dreams, a famous internet poetry troll, he’s probably better known for crap like “Best American Poetry: The Cartoon”, “Stone Cold Poetry Bitches” and “What the Hell is Up With Your Author Photo?” Behrle really has to get more of that Ruth Lilly money somehow.

by Jim Behrle

Jim Behrle has a half inch penis

The Kill List Kid has a three inch penis

Vanessa Place has a six inch penis

Billy Collins has a four inch penis

The Poetry Foundation has a $100 million penis

But Poetry Magazine has a two inch penis

Your iphone is a mile long penis that’s

Always secretly fucking you

When you look at your iphone think “penis”

Google is a huge penis sticking out of

Everything everywhere

And where ever you go you bump into them all

Poetry is a huge warm wonderful vagina

But everyone treats it like a narrow

Tight, unbreakable asshole that only

One penis at a time can fit in so

You’ve got to out-penis everyone else

Manhattan and Brooklyn take an inch off

America’s penis is old and gross

But we’re working on it now

The internet takes a half

Inch off your penis, snip, snip

Let’s just cut off all penises

Or yank them all out by the root

What will survive is love

And penises usually fuck that up, too

Kafka once wrote “We are incapable of loving, only fear excites us.” Behrle quotes this all the time, it is the only thing he’s ever read from Kafka. And he wants to sound smart. This poem began as a long list of poets and their perceived penis lengths but once he got to the line about Billy Collins penis he lost his stomach and turned it into something else. Vanessa Place’s penis on the other hand kills poetry every night, aw yeah. Behrle. . .

Kafka once wrote “We are incapable of loving, only fear excites us.” Behrle quotes this all the time, it is the only thing he’s ever read from Kafka. And he wants to sound smart. This poem began as a long list of poets and their perceived penis lengths but once he got to the line about Billy Collins penis he lost his stomach and turned it into something else. Vanessa Place’s penis on the other hand kills poetry every night, aw yeah. Behrle. . .

note: I’ve started this feature up as a kind of homage and alternative (a companion series, if you will) to the incredible work Alex Dimitrov and the rest of the team at the The Academy of American Poets are doing. I mean it’s astonishing how they are able to get masterpieces of such stature out to the masses on an almost daily basis. But, some poems, though formidable in their own right, aren’t quite right for that pantheon. And, so I’m planning on bridging the gap. A kind of complementary series. Enjoy!

November 8th, 2013 / 9:24 am

Where I Learned To Escape

From ages 19 to 22 I was a lifeguard at the same tiny motel pool each summer in upstate New York. When the owner asked if I wanted to work full-time (this was at the start of the second year) I tried to suppress my enthusiasm because it was the easiest and most relaxing job ever. I said not to hire anyone else, I would run the pool full-time. I worked from sunrise to sunset seven days a week sitting under a blue umbrella at a plastic table with a tower of books. Occasionally, I interacted with the motel guests who viewed me the way inhabitants of Florida view snow.

25 Points: This Is Between Us

This Is Between Us

This Is Between Us

by Kevin Sampsell

Tin House Books, 2013

240 pages / $15.95 buy from Powell’s or Amazon

1. This book reminded me of this remix which was incredibly moving and pained me this spring and still pains me now http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KbdOBE1ORw

2. The thing about Kevin Sampsell is that he feels like the kind of guy who has been through everything. He’s just one of those people. He doesn’t have that used up feeling or look at all but he does have that vibe of being the kind of guy who has lived through basically everything there is as a human to experience but not in a hardened way.

3. I’m not explaining this right but he’s just one of those people who seems complicated and well adjusted and like if you talk to him he just has been there, whatever it is but he doesn’t come outright and say that instead he just comes from this I know what you mean mode which isn’t even patronizing the point here is that all of that also comes through in his writing and this book This Is Between Us from Tin House coming out is five years of a life.

4. Anything you have ever experienced in your life is in this book.

5. This book is comforting.

6. Sometimes this book is upsetting.

7. This book is comforting.

8. Some people said this book was disturbing and I was like have you ever lived your life at all or ever really loved someone or had a partner and if you haven’t maybe your life is easier and even if your life has been really nice you’ll still be like “yup” while reading parts of this book because it’s just so real in how it’s rendered because it’s just written so elegantly and simply stated and maybe that’s the thing with Kevin Sampsell’s writing.

9. We’re working with the rhetorical you in this entire book.

10. It’s written like a confessional ode-ish poem. READ MORE >

November 7th, 2013 / 1:06 pm

Video Review of The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting Improvised Men by Gabriel Blackwell

Trays of live worms for consumption, a nightly stroll with the shells of dead animals, and an arm covered in yogurt and soy sauce that smelled like strawberry grease for a whole afternoon; these are the ingredients for this new video book review of Gabriel Blackwell’s book by Gabriel Blackwell and meta-Gabriel Blackwell from CCM. I don’t know which of them is real. I think I’ve been hypnotized by Joseph Michael Owens’ music tracks. But I didn’t make this video. My wife did. She says she’s never seen any of the footage included and doesn’t understand why I’m crediting her. I don’t like strawberry soy sauce covering my arm so that my hands are unctuously melting into my chest. I’ve never eaten living worms before. I need to go back to America and have cheeseburgers made of artificial cheese and meat so I can have a culinary epiphany and shit out truths inspired by film cuts of scatological epics. You should read The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men from CCM by Gabriel Blackwell reviewed by Peter Tieryas Liu and Angela Xu with music from Joseph Michael Owens and edited by Janice Lee.

(Read the previous review on HTMLGIANT here)

November 7th, 2013 / 11:49 am

An Interview with Sophia Le Fraga

Sophia Le Fraga’s I RL, U RL has just been released from Minutes Books.

Andrew Worthington:

Where are you right now?

Sophia Le Fraga :

I am…FUCK…I am at work, at the Hearst Tower.

AW:

What’s your job?

SLF:

I’m a copywriter and editor at this digital ad agency.

AW:

How’d you get that job? What sorts of ads do you do?

SLF:

Well so, I studied Linguistics at NYU and when I graduated, I was just all over the place, traveling up and down the California coast kind of like aimlessly, and one day this guy called me and was like, “oh NYU said that you could tutor me in Syntax and Semantics”, and I was like, “Yeah sure” and he was like, “ok be in touch when you’re back.” And when I got back, I hit him up to tutor him a couple of times a week, and when we met he was like, “I’m the SVP of this ad agency, do you want to just like… work for me?” And I was like, “Well it’s not like I’m doing much of anything else…” So that’s how I ended up here. I do all kinds of ads, from skin care stuff to like cable and internet stuff to banks and cancer treatment centers…it tends to be…an eclectic bunch.

AW:

Did you take writing classes when you were in college? Or was writing something you did on the side sort of?

SLF:

Yeah totally. NYU didn’t offer a Creative Writing major but I pretty much took enough credits to double up. I took a lot of poetry, some fiction, and for two years, did an independent study with Rob Fitterman on “Poetry of the Avant-Garde”. I feel like writing was always what I wanted to do, but I wanted to have the background in Formal Linguistic to kind of… better understand what I was doing.

*Linguistics

AW:

Can you describe some of the ways you may go about writing poetry? How did you compose I DONT WANT ANYTHING TO DO WITH THE INTERNET?

SLF:

Well, so, I DON’T WANT ANYTHING happened after I submitted a sort of “open call,” asking everyone I knew on Facebook, Twitter and e-mail if they wanted a “poem”… and depending on what medium they responded in, I took from their feed, or their wall, or their e-mail and gave them each a poem of sorts, using only their language. People love to hear themselves talk.

AW:

So I guess no one was upset with the poem you made for them, then?

SLF:

No, of course not! All I gave them was a word salad of whatever they’d already shared on the web.

But that’s not to say that people haven’t been upset with me. That’s all pretty extensively catalogued in “H8M8” [a section in I RL, U RL].