an excerption of an excerption in the breakdown of the bicameral mind

2. Excerption. In consciousness, we are never ‘seeing’ anything in its entirety. This is because such ‘seeing’ is an analog of actual behavior; and in actual behavior we can only see or pay attention to a part of a thing at any one moment. And so in consciousness. We excerpt from the collection of possible attentions to a thing which comprises our knowledge of it. And this is all that it is possible to do since consciousness is a metaphor of our actual behavior.

Thus, if I ask you to think of a circus, for example, you will first have a fleeting moment of slight fuzziness, followed perhaps by a picturing of trapeze artists or possibly a clown in the center ring. Or, if you think of the city which you are now in, you will excerpt some feature, such as a particular building or tower or crossroads. Or if I ask you to think of yourself, you will make some kind of excerpts from your recent past, believing you are then thinking of yourself. In all these instances, we find no difficulty or particular paradox in the fact that these excerpts are not the things themselves, although we talk as if they were. Actually we are never conscious of things in their true nature, only of the excerpts we make of them.

READ MORE >

Interview with the editors of CATCH UP Magazine

The editors of Catch Up were kind enough to answer a few of my questions about their badass journal.

How did Catch Up emerge?

Jeff: In the early 2000’s, William Cardini and I founded the artist collective The Gold County Paper Mill. Together with our pal Chuch, we produced comics, zines, and weirdo DVDs. But in 2008, I moved with my wife from Austin to Louisville, which meant the performance art we were making together would become fairly impossible. Catch Up started as a way to continue the collaborative projects that WIlliam, Chuch and I had grown to love.

Catch Up was intended to be an object-based series of collaborations put out by the GCPM. The “first issue” was a t-shirt. That idea fizzled out quickly. Having enjoyed producing our own books, we decided to try our hand at publishing others. Will is a cartoonist and I’m a poet, so we just mushed those two things together.

Once in Louisville I met poet Adam Day and designer Rob Bozwell, who both quickly joined the team. Will enlisted the help of another frequent collaborator of his, Josh Burggraf. The five of us turned Catch Up into the fucking dope journal it is today.

After a few more shake ups, moves, marriages and babies, Catch Up is now run by myself, Hannah Gamble, Gary Jackson, Peter Jurmu, Pete Toms and PB Kain.

What is your VIDA count?

Give & Take: A Conversation with Exxon Mobile/Mellow Pages

(photo credit: JoAnna DeLuna of Bushwick Daily)

When news broke about the Mellow Pages “hoax,” I wasn’t laughing. Actually, I was downright pissed. After a few days, though, I realized that my anger didn’t lie with Matt and Jacob—or Mellow Pages or Exxon Mobile or Kanye West—but with myself. I reacted in a very solipsistic way: I had contributed to their Indiegogo campaign; I am a member of the library; I’ve donated (and will continue to donate) a copy of a Big Lucks book to the library; I’ve recommended that people check out the library and contribute to their campaign and visit the space and get to know those cool bros. I wanted them to stay open. But why hadn’t I done more? Do I even have a stake in Mellow Pages? Would things have changed if I suggested something besides “take the (fake) money and run?” And why does my opinion matter in the first place?

I mentioned to Matt and Jacob that I planned on writing about my reactions to their project. After a few emails, we decided it might be more valuable to just talk. The conversation is messy, disjointed, long, and probably very rudderless. But I still think it’s important. Because if there’s one thing this project has taught me it’s that there’s no cut-and-dry formula to support our community.

Of course, we’re all contributing something here. I am but one minuscule cog in the refurbished turbine engine that powers this rinky-dink dirt bike. Whether it’s money or time or love or futons, we all give something. But we can’t say that we all expect the same thing in return for our support. Maybe that’s not good. Maybe that’s a problem.

So maybe it is worth keeping this conversation alive.

—

Mark: When did you guys decide to go ahead with “#Mellowghazi?” Was it a spur-of-the-moment decision, or had you been plotting/planning for a while?

Matt: First off my man, Mellowghazi, the term, is not our doing. And isn’t in line with what we were thinking. We weren’t doing it to be funny. We took what we did very seriously. People feel quickly. Especially on the internet. Mellowghazi is a reappropriation due to that quickness, a way to divert direct contact with what was happening through a comedic cloud. People need time to think. I mean, I hate to start this way, but reflection eternal, like Talib says. You got to keep slowing down and think about the water, whatever the fuck that means.

Sad & Hyperreal: Tracing Science Fiction Poetry Through Andrew Zawacki’s Videotape

Videotape

Videotape

by Andrew Zawacki

Counterpath Press, 2013

128 pages / $14.00 Buy from Counterpath or Amazon

“Science fiction poetry” is already a confusion of forms, a mash-up of brainy and hoity, nerdy and emotional, clunky and raw. If both science fictional and poetic, must this inter-genre be narrative-oriented, pithy, lyrical, and riddled with lasers? What else can we call it? “Science poetry” doesn’t account for future-speculation per se. “Cyberpoetry” resonates with cyberpunk and prescribes the rubric for an internet made 3D—strung up with tubes every shade of the neon rainbow. William Gibson himself, the supposéd godfather of cyberpunk, rejects the term applied to both his and his contemporaries work because it reduced what could’ve been a revolutionary alteration on the larger science fiction genre to a subgenre and therefore made it separate and disarmed. “Futurist” or “neo-futurist poetry” already has its predecessors in Marinetti, Mayakovski, and the like. “Speculative poetry” becomes overwhelmingly broad and “futurepoem” has already been claimed by a fabulous small press. For now, we’ll stick with science fiction poetry because everyone knows what we’re talking about when we say it, and any discussions based around the term should necessitate we at least acknowledge it as a genre that will be constantly at war with itself, a form containing two disparate worlds, that, most of the time, would probably rather not have anything to do with each other in the first place.

Many have gone to extreme lengths to define both poetry and science fiction separately and they are indelibly linked by a desire to write down what cannot possibly ever actually be written down. Ben Lerner talks about an Allen Grossman essay called The Long Schoolroom in his Believer interview, citing that Grossman calls all poetry “virtual” because it explores “an unbridgeable gap between what the poet wants the poem to do and what it can actually do.” For the world of poets, while our want may be for access to that Platonic ideal hovering above, we are also caught up in an inevitable failure to ever reach that world. So it is for science fiction writers, except they are concerned with the future rather than the divine. Where they may use the vocabulary of science and technology in order to provide insight into how the nuances of that future may one day appear, poets look to music, linguistics, and extreme concision in order to record their pursuit of those sublime, unknowable moments of everyday life. The rest is simple addition. Science fiction plus poetry equals a work that looks to material “progress,” the sonic, semiotics, and the pages white space in it’s pursuit of both spiritual transcendence and a prophecy for that grand tomorrow.

Another way to define a genre, as always, is simply to point the people who practice that genre well. Cathy Park Hong discusses science fiction poetics in one of her Harriet posts, where she outlines Andrew Joron’s Science Fiction, the most committed exploration of science fiction poetry to date. Hong dabbles a bit in the genre herself in Dance Dance Revolution and the “The World Cloud,” the third section of her own Engine Empire, with poems like “Engines Within the Throne” and “A Wreath of Hummingbirds.” There are countless others who’ve taken a crack at science fictionish projects in recent years. From genre-poets like Hong to conceptual writers like Christian Bök, to Pulitzer prize winners like Tracy K. Smith, everyone seems to be getting a piece. Bök isn’t interested in the conceits of science fiction as a genre, but is willing to spend nine years in a lab teaching the genome of a bacterium to store and write a poem that should last long after the human race is extinct. He calls it The Xenotext and however outlandish the project may seem, he has had a surprising amount of success. Other Conceptual poets, like Kenneth Goldsmith and Josef Kaplan, construct poems dependent on their own machines. Goldsmith’s projects succeed or fail based on how they are figuratively programmed to reproduce. The common language in his transcriptions of news anchors and weathermen are interesting because he captures human malfunctions in otherwise robotic speech, while the success of Kaplan’s Kill-list depends on the rage it provokes in the hivemind’s many forums and comment threads on the web.

“It’s all science fiction now,” is the oft-quoted phrase in these sorts of discussions, which Hong transmits from Joron and which Joron beams-up from Allen Ginsberg and Arthur C. Clarke. We’re turning to the futures of the past in order to interpret a society more and more affected by accelerated progress. Indeed, the list of poets goes on—Heather Christle has poems that unabashedly employ zeros and ones, cybernetic trees, holograms, and sublime computer programs in What is Amazing and elsewhere. Modern Life by Matthea Harvey contains a series of poems about a robotic boy and his half-human perceptions. Ben Mirov tracks the clicks of our increasingly cybernetic brains in Ghost Machine; Mathias Svalina obsesses over the beginnings and ends of all things in Destruction Myth; Timothy Donnelly offers the sky for purchase in Cloud Corporation; and Jasper Bernes enacts a dystopic LA in Starsdown. Even Pulitzer Prize-winner Tracy K. Smith toys with future-speculation in Life On Mars. Johannes Göransson and Joyelle McSweeney proclaim themselves Futurist in their Action Books manifesto, and McSweeney revels in a future plague ground, a poetics of doom, in much of her own writing and criticism. After all, Tao Lin is basically Neo, who opted out of The Real and instead chose to remain dangling in his giant pink egg sac, so long as he had access to a Macbook Pro.

January 17th, 2014 / 11:00 am

The Best American Comics 2013

The Best American Comics 2013

The Best American Comics 2013

Edited by Jeff Smith

Series Edited by Jessical Abel & Matt Madden

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Oct 2013

400 pages / $25 Buy from Amazon or Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

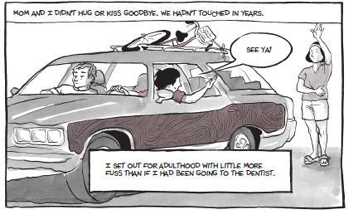

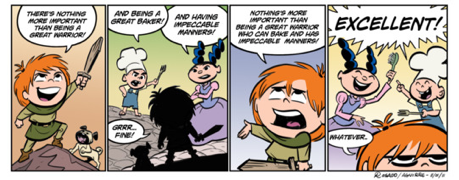

The Best American Comics series is an anthology of comics, published annually with numerous guest editors, showcase what the editors feel are the best comics of the year. This edition contains thirty comics; some of them being complete, and others excerpts from larger comics. What is also nice to see is the vast majority of webcomics that are included in this edition, such as Kate Beaton’s tumblr famous ‘Hark A Vagrant!’ series. And although different, these comics all seem to share something in common, something ethereal that seems to connect these pieces all together that I can’t quite put my finger on, and I am glad that I have trouble doing this.

One of the things that I think brings the comics together is the feelings of anxiety that the characters seem to have. As I was reading the collection, I couldn’t help but think that they all seemed to be looking for something; in Alison Bechdel’s Mirror, the protagonist is searching for not just her own identity, but also seems to be searching not just for her mothers approval and love, but for her mothers identity, as well as trying to find her own place in the world. I think that the search for purpose and identity, although not just central now, as It has been a common problem for centuries, speaks to a generation raised in the internet age, one that has tried to find a personal identity through the lives of millions online.

In You Lied To Us!, by Jorge Aquirre and Rafael Rosado, the protagonist, a little girl, lies to her friends in order to look for, and slay, a local giant. Here, the protagonist is trying to create her identity through tackling the giant on her own, but in confidence is scared and alone. I think that this narrative, the David and Goliath story, echoes throughout a lot of us in our modern day lives; we want to tackle giants on our own, but we are too afraid and lack the skills to do it, and asking for help can make one appear weak. Although, like the previous comic, this is not a new narrative, I do feel that this story seems to hit at the centre of our shared anxieties. We live in a world of self made millionaires, twenty somethings who changed the world, who appeared to do it on their own, indadvertedly causing an entire generation to feel like they have to go it alone as well

Faith Erin Hicks Raiders also talks about individualism, but does so in a different way. The protagonist retrieves what appears to be an artifact of some kind, to return to a ghost seeking some sort of atonement. She does this with the help of her friends at first, but decides to sneak of an seek out the ghost alone, thinking that her friends will think less of her. It appears, despite not finding atonement through the ghost, that her friends also see the ghost, which gives to her a different kind of atonement, causing the ghost to leave. I feel that this seeks to tell us that going it alone is intact damaging, showing one that we all have hidden doubts and fears, here symbolized by the ghost, and sharing these fears and doubts is healthy, and one can overcome the giant, or the ghost, by reaching out to those around you.

What is also interesting to note is how different each piece is from another aesthetically. Each comic in this anthology is distinctly unique in its artwork, ranging from the almost life like, which can be seen in Mirror, to the surreal and weird. Some comics are full of texts, others nothing but a series of images. What is fascinating to note is that they are all able to tell a story, regardless of the way they do so, full of as much power, emotion, and expertise as one would find in a more ‘traditional‘ piece of fiction, such as a novel.

In editing the anthology, the editors seem to be aware of the problems the artists are trinyg to tackle, subconsciously or actively, and are seeking to address these problems through the anthology. What is clever about the addition of the webcomics is that a lot of these problems, of identity and feeling isolated, are ironically magnified by our existence in an online world, but can also be cured by our participation in the same world. One can construct our identities through others; our mothers, stories of great people, our friends, but we aren’t really able to overcome these anxieties and self doubt until we try to identify with ourselves, by confronting our doubts, opening up to our community, and just being ourselves. I feel that this is one of the central messages of this anthology; a reflection on the way we interact and inhabit the world has so drastically changed that we haven’t had the time to catch up to it yet.

***

Rhys Nixon is a writer who lives in Australia. He has been published in electric cereal, Gesture magazine, and posts occasionally on his blog, rhysrhys.tumblr.com.

January 17th, 2014 / 10:00 am

25 Points: The Circle

The Circle

The Circle

by Dave Eggers

Knopf, 2013

504 pages / $27.95 buy from Powell’s or Amazon

1. Nothing about The Circle is very surprising or new. Big Brother is a clichéd, outdated reality show. The privacy vs. transparency debate is as ubiquitous as the scope it describes. It’s obvious from page one which side the novel will end up on.

2. I don’t care about any of this. The transparency-obsessed campus of The Circle (a proxy for Google) is not an unappealing environment to me. Most of the time, it’s ridiculously attractive.

3. The relentless lists of online activities that the protagonist, Mae, conducts daily are not the downward spirals of doom they should be. Instead, the repetitive passages feel hypnotic and pleasurable and I live vicariously through Mae’s Internet high. I should read her decline into web addiction and over-sharing critically, but instead I feel the same breathless, click-through-again compulsiveness that I do staying up too late online, browsing websites and managing my own social media accounts.

4. I can’t figure out if I’m the exact target audience for The Circle, or the exact opposite of it. Are its warnings meant for those younger than me who’ve never known a world without Google? Or those older, who take a certain pride in refusing to get an Internet connection or email account?

5. The novel circles around the same few themes, visits the same few locations, and its protagonist, Mae, repeats the same tasks over and over again. This repetition gives me an intense, almost physical pleasure: a caffeine-like tightness in my brain, behind my ears; a lifting in my chest; the impulse the read as quickly as possible.

6. It’s more engaging to read about what Mae does on her computer than about her interactions with human characters, who are consistently flat—placeholders for perspectives.

7. Internet Rorschach: is this passage a dark chute of terror or an energizing, endorphin-generating endurance run? “[Mae] embarked on a flurry of activity, sending 4 zings and 32 comments and 88 smiles. In an hour, her PartiRank rose to 7,288. Breaking 7,000 was more difficult, but by 8, after joining and posting in 11 discussion groups, sending another 12 zings, one of them rated in the top 5,000 globally for that hour, and signing up for 67 more feeds, she’d done it. She was at 6,872, and she turned to her InnerCircle social feed. She was a few hundred posts behind, and she made her way through, replying to 70 or so messages, RSVPing to 11 events on campus, signing nine petitions and providing comments and constructive criticism on four products currently in beta. By 10:16, her rank was 5,342, and again, the plateau — this time at 5,000 — was hard to overcome. She wrote a series of zings about a new Circle service, allowing account holders to know whenever their name was mentioned in any messages sent from anyone else, and one of the zings, her seventh on the subject, caught fire and was rezinged 2,904 times, and this brought her PartiRank up to 3,887.” The passage continues for several more pages.

8. Fiction Writing 101: A complex character should always want something. For effective character development, ask: what does the character want? Mae wants a job at The Circle, and she gets it on page one. Her character is empty, simplistic, a shell.

9. Perhaps stripping Mae of any real wanting is the novel’s innovation: what happens when we want for nothing? Are we human anymore, or just shells of ourselves?

10. Something Mae sort of wants is a good rating of her work at The Circle (99% or higher for every inquiry she answers, which number in the hundreds each day). But this obsession with approval and high ratings doesn’t quite ring true to me: with quantity comes ambivalence, not a desire for quality. When reviews are always perfect, they have no meaning. READ MORE >

January 16th, 2014 / 4:38 pm

Pretty Owl Poetry is a new online journal and they’re looking for submissions. Send them something shameful, they say, or surreal, or a tooth.

POEM-A-DAY from THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN LUNATICS (#11)

Penny Goring lives in London. She makes things, and collaborates with Hella Trol Buzy to make other things.

please make me love you

by Penny Goring

![]()

i wrote it on new years day. i used that can be my next tweet, getting computer generated mashups of my recent tweets, then reshuffling, discarding, and adding words. when a line is done i tweet it. because: it’s faster than opening another tab, it makes writing less lonely, it’s interesting to see what lines get favd/retweeted/ignored, and seeing my lines in the twit stream helps me get distance. when i felt like i’d made enough, i copy/pasted each tweet into openoffice and did edits. i like repetition, variations. i feel self-indulgent when i write lists – it is a falling. on new years day i wanted to fall in love.

when a line is done i tweet it. because: it’s faster than opening another tab, it makes writing less lonely, it’s interesting to see what lines get favd/retweeted/ignored, and seeing my lines in the twit stream helps me get distance. when i felt like i’d made enough, i copy/pasted each tweet into openoffice and did edits. i like repetition, variations. i feel self-indulgent when i write lists – it is a falling. on new years day i wanted to fall in love.

![]()

note: I’ve started this feature up as a kind of homage and alternative (a companion series, if you will) to the incredible work Alex Dimitrov and the rest of the team at the The Academy of American Poets are doing. I mean it’s astonishing how they are able to get masterpieces of such stature out to the masses on an almost daily basis. But, some poems, though formidable in their own right, aren’t quite right for that pantheon. And, so I’m planning on bridging the gap. A kind of complementary series. Enjoy!

January 15th, 2014 / 8:39 pm

Interview With Luis Panini

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Luis Panini is one of the most talented writers you’ve never heard of. With writing that recalls the best of Franz Kafka, Lydia Davis, David Foster Wallace, and Julio Cortázar, it is a regret that his writing can not be read in English (until now! see below). I recently sat in on a class at CalArts where he was a special guest in my friend Laura Vena’s class on Latin American literature, and it was a huge pleasure to hear him talk about his writing and thought processes. Laura Vena translated a few of his short stories (or fragments) into English, the results of which can be found below, and so I’m hugely happy and excited to share this interview here and debut these new translations of his work into English.

Janice Lee: In your other life, you’re an architect and furniture designer. I’m interested in how this work and mode of thinking influences your stories. For example, the preciseness of your language, the constructedness of your stories as rigid and stable structures, your attention to spatial details and spatial relationships, and the existence of people and objects in physical environments rather than in relation to each other.

Luis Panini: My academic background has not only influenced the way in which I think about stories before I actually write them but also it has made me think about overall structures when I am constructing (not writing) a book, whether is a collection of short fiction, a novel, a book of poems or some piece of writing that does not necessarily falls into these ankylosing categories. Spatial awareness is very important for me since it is ultimately where the “game is played” and this is why I frequently try to inject some sort of symbolic meaning to both, the spaces my characters inhabit and the objects they come in contact with. In a way, what I am trying to accomplish is to integrate these “architectural objects” into the narrative in such a way that these become as important as the characters or the story itself. It is about translating the mere functionality of a space or an object into an emotional component in the writing process or how this space or object is acknowledged and assimilated by the reader. Duchamp’s “Fountain” comes to mind. He managed to transform a simple urinal into an object charged with many layers of meaning by placing it within the confines of a “sacred space.” Outside the museum, Duchamp’s piece is nothing but a urinal. Inside the museum is everything but a urinal because the reading conditions of this object have been transgressed. This is the sort of relationships I like to establish between my characters and the space they move about.

JL: You’ve described your stories as vignettes or fragments, and I think they operate in this way, but too, at the same time, they seem like such self-contained and intentionally built structures that do have set boundaries. Can you talk a bit more about the general shape of your individual stories?

LP: I did refer to those texts (the ones collected in my second book) as vignettes or fragments because that is truly what these are. They are absolutely self-contained pieces of writing. I like to think that the most interesting building block in writing is not the sentence, the paragraph, the chapter, etc. but the fragment, because a fragment does not require a beginning or an end, it does not need to tell a whole story to work, it does not have to acknowledge the fragment that precedes it or follows it and I find this to be truly liberating, a sense that I do not get when I take a different approach. About a year or two ago I finished writing a book that deals with memory and it is comprised of more than one hundred fragments. There are two versions of that book. In one version the fragments follow a chronological order of events and in the other version the fragments appear in the order in which they were written, the order in which I remembered a loved one who died recently. I chose to write about that story through fragments because in a way I wanted to emulate the mechanisms of memory and a fragmentary approach made perfect sense since I could experiment with the elasticity of the overall structure (or lack of one) by allowing a virtually infinite number of permutations. This also allowed me to set very strict boundaries on a fragment bases that I had to respect as I was writing each line. Every time I deviated in any way from those boundaries, the fragment did not work. It felt like an ill-conceived part of a whole. Through this method of writing I learned about the shape of not just individual stories but also how these can be connected in a book and how they interact among themselves by borrowing, cannibalizing from each other, etc. A book composed of fragments can be dozens of different books, only limited by the sequence you end up choosing.

JL: I know you are a Béla Tarr fan too, and I find that there are some resonances in your work with Tarr’s fans. For example, the focus in your stories is often on a person’s existence in a space or situation, and the story settles in on the details of the environment, constructing a scene that becomes a sort of story, rather than a story that is based on action and resolution. This reminds me of the indifference of the camera in Tarr’s films too, where often the setting is there before a character enters, and remains there after the character is gone. What are your thoughts on this observation?

LP: Sometimes I think that filmmakers are the ones who truly influence my creative process and writing methods, much more than literature in general or specific writers and books, and this has nothing to do with the fact that I live in Los Angeles, a city in which if you mention that you are a writer most people immediately ask you what screenplays have you written. Béla Tarr is one of these auteurs (I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed seeing that old man peeling potatoes in “The Turin Horse”), but also I am fascinated with the way other directors choose to tell stories, like Michael Haneke, Yorgos Lanthimos, and my personal favorite Ruben Östlund. I am not trying to say that my literary work has a cinematic quality or that it could easily be translated onto the screen, but this element becomes quite obvious since I tend to favor heterodiegetic narrators in most of my texts. I like to take it to the extreme, turning them into machine-like narrators which can be perceived as actual cameras panning through multiple rooms in a residence to create some sort of long shot composed by zoom-ins, abrupt cuts, blurs, etc. My vignette titled “The Event” is an example of this. After the character has “disappeared” in a very tragic way the camera goes back into the apartment where it all began and stays in recording mode to capture the solitude of the space, which to me is far more important than the demise of the actual character. In another vignette the narrator also acts as a camera that moves inside of a mansion to capture many of the possessions of a lonely man dying of complications related to an immunological disease. I was not interested in that man’s story specifically, but in how I could construct one by describing the pieces of furniture and ornaments he owns, the art hanging on his walls, and the materials and finishes of his home. I guess by doing this I am trying to illustrate some sort of terror that sometimes keeps me awake at night, the fact that after one dies everything else remains in its place, unaltered, because we are that insignificant. And it is this sense of pervasive malaise what informs most of my writing.

JL: I’m affected deeply by level of compassion and human dignity present in Tarr’s fans. On this subject, Andras Balint Kovacs writes:

“The man, whose philosophy despises ‘humanist’ feelings like compassion and pity, suddenly and certainly unwillingly, manifests the deepest compassion for a helpless living being, a beaten horse. This event, says Krasznahorkai, is ‘the flashing recognition of a tragic error: after such a long and painful combat, this time it was Nietzsche’s persona who said no to Nietzsche’s thoughts that are particularly infernal in their consequences.’ This is the example which leads to a conclusion about the universality of this feeling: ‘if not today, then tomorrow… or ten, or thirty years from now. At the latest, in Turin.’ … an attitude or an approach to human conditions, which Tarr fundamentally shares with Krasznahorkai… Both authors have a fundamentally compassionate attitude toward human helplessness and suffering in whatever situation it may manifest itself, and of whatever antecedent it may be the result.”

In Tarr films, compassion can exist without moral judgment, or, in other words, “In the Tarr films human dignity is not based on morality. It is based on the fact that in spite of their absolutely hopeless and desperate situations the characters remain what they are, however low what they are brings them.”

This simultaneous closeness and distancing, this empathy is ever-present in your stories for me too. For example, in “Mathematical Certainty,” there is a deep care in the description of the hat, but also in the generous curiosity afforded to the man with the brain tumor. I also recently heard Lydia Davis talk about description, and said something like, “In order to describe something, you have to love it. Even if it’s ugly, like an old shoe, you have to love it in a way to really describe it.” The preciseness of your language and the kind of curiosity afforded by such a detail as the length between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, seems like a generous gesture in a way. What are your thoughts?

LP: I believe empathy and compassion is what drove me to write the vignettes included in my second book, as strange as that may sound given the dark nature of the overall subject matter of those texts, which is ill will. In fact, I can pinpoint the exact moment that acted as the catalyst. Back in 2006 there was a terrible brush fire, which consumed an enormous area near Los Angeles. For some reason that I yet have to comprehend a news show chose to broadcast a recording with no “viewer discretion advised” warning beforehand. I saw the body of a fallen hare partly carbonized. It was still moving, shaking the rear legs, convulsing, agonizing. And it affected me so much because animal suffering is something I simply cannot deal with. So this visceral reaction prompted me to explore this feeling in different ways, in fact so many that soon became a book about ill will. Ill will towards animals, patients with terminal diseases, sexual partners, art, even towards the reader. The main character in “Mathematical Certainty” is a man who soon will die of a brain tumor he has chosen not to have surgically removed. Instead, he decides to buy a white hat to conceal, maybe in an unconscious way, this organic tissue developing inside of him. Growing up in a predominantly catholic environment I heard many people say that the real reason why a man or a woman got cancer was the result of divine punishment, as if sinful behavior (whatever that means) could trigger it. So, in a way, that particular vignette is about religious ill will, the supposed shame caused by the disease, thus the comparison between the hat and a crown of thorns. Again, I was not too interested in the life of this character, but in presenting a juxtaposition of elements, such as a man fully dressed in white with something truly dark growing inside of his skull, and more so in determining the distance between the interior wall of the hat and the tumor, because those particularities or insignificances are what fuel my desire to write. I don’t want to write about the victims of a serial killer or the reasoning behind his actions, instead I want to write about the way in which this terrible person peels potatoes.

January 15th, 2014 / 10:00 am

……All Day I Will Fuck Poetry like Hiromi’s Tongue– Ito, Ito, Ito, Ito, Ito……

***

today is National Dress up Your Pet Day (ok, sure, come here, doggie)

today is also National Hot Pastrami Sandwich Day (yeah, I’m hungry. sure, why not)

and (sigh) today is National Poetry at Work Day (knife in stomach)

***

January 14th, 2014 / 5:45 pm