A Conversation with Philip Graham

Three of Philip Graham’s early books are newly available in Dzanc/Open Road ebook editions. Graham asked me to write the introduction for one of them, The Art of the Knock, and while I was working on it, I asked him a few questions to satisfy my curiosity about his years working with Donald Barthelme and Grace Paley, his time in Africa, and his thoughts on symmetry and design, which are influenced in part by the poetry of Charles Simic and the plays of William Shakespeare.

Three of Philip Graham’s early books are newly available in Dzanc/Open Road ebook editions. Graham asked me to write the introduction for one of them, The Art of the Knock, and while I was working on it, I asked him a few questions to satisfy my curiosity about his years working with Donald Barthelme and Grace Paley, his time in Africa, and his thoughts on symmetry and design, which are influenced in part by the poetry of Charles Simic and the plays of William Shakespeare.

Kyle Minor: I’ve just finished re-reading The Art of the Knock, the book that first brought you to the attention of many readers. I was struck by its symmetries of design, a thing that seems to have been a preoccupation of yours. So many story collections are simply a grab bag, a greatest-hits-lately. But The Art of the Knock is, first and foremost, a book. The parts are in conversation, and they are arranged like a series of Chinese boxes, or Russian matroyshka dolls, on the one hand, and on the other, they are directional. We begin with digging through toward China, and we land in China. We go through three iterations of the “Art of the Knock” series. And the rest of the stories are nested in two in-between sections that seem mirror images one of the other, or at least they are in conversation. How did you find the form of that book? Did you write your way into it, or did the design arrive first?

Philip Graham: Actually, The Art of the Knock grew out of a combination of the two approaches. I’d just published a first book of prose poems, The Vanishings, and my new work was tending toward the short story form. I’d written the first China piece, the first Art of the Knock story (though at the time I didn’t consider them part of a series, they just were what they were), and a few of the family stories—“Silence,” “Shadows,” and “The Distance.” I was simply working my way into a new book, and didn’t have a definite sense of what it might become. READ MORE >

Virtual Book Tour: Bonnie ZoBell

Follow Along With Bonnie’s Virtual Book Tour Using the Link on the Banner!

Bonnie ZoBell rants about sex and the elderly:

Who is it that thinks old people shouldn’t have sex? Miguel in my story “Lucinda’s Song,” that’s who. Miguel—and he’s not alone—thinks his eighty-year-old mother, Lucinda, has no business romancing at her age, especially not with someone who isn’t his father, even if his father has been dead for years. For her part, Lucinda’s having a great time with her new beau, Ramón Fernández. In fact, they’re having such a torrid affair, she can’t get around to watering her lawn and keeps getting citations from her gated community for having brown grass. She’s never had so much fun.

And why shouldn’t she, or any other elderly people? There’s no threat of pregnancy anymore. In older generations, when birth control wasn’t as widely available, extramarital as well as marital lovemaking always came with the risk of pregnancy if women were just looking for a little pleasure. Additionally, their adult lives have been spent working themselves practically to death, at least until they retired. They’ve raised children, paid their taxes, lived in wedded bliss—or not so much bliss—and many are now living alone. Don’t they deserve having as much of the old in and out as they please?

We’re too plugged in to the airbrushed beautiful people advertisers keep throwing at us. The older we get, the more we discover that looks aren’t what it’s all about anyway. Maybe both people in an elderly couple enjoy European history, watching Glee, and naps in the afternoon. For Lucinda and Ramón, weekly bingo really turns them on. He likes her ‘tude. She’s always liked Indian-looking men. Why shouldn’t they get it on?

Miguel isn’t a bad guy. I try to understand him, because I invented him after all, and I care about all my characters. I try to understand that with his dad gone, he might feel a certain protectiveness about his ma, doesn’t like to think of her that way. But come on, guys, her parts are all working and she got along just fine before you came along. Miguel particularly doesn’t appreciate finding a bottle of personal lubricant on his mother’s kitchen counter—or that she’s threw her back out when she and Ramón were going at it against the dishwasher. Get a life, Miguel! If the sex is good enough for her not to mind a small injury, you need to move on!

Remember, if our mothers didn’t have at least a small interest in sex, we may never have been born. If you have to say something, tell her you care about her and want to be sure she’s using protection. Did you know that STDs have doubled in 50 to 90 year olds in the last decade? They’re living longer. With so many medical breakthroughs over the last century, bodies are staying healthier longer, or at least healthy enough to enjoy physical pleasure. Retirement communities are like rave parties these days. It’s no longer all about shuffleboard, looking at scrapbooks of grandchildren, or dusting cat figurines.

Lucinda and Ramón have their own particular way of making love, slow and how they like it:

“Come with me, mamacita,” Ramón said when they’d finally said what they needed to say and decided to make love. That night he helped remove her shift, she his trousers. The dim light from the bathroom bathed their wise, desirous bodies. Ramón smoothed the skin on her neck for such a long time it felt like a shiny sea stone. She ran her nails over his back until he drooled.

“Don’t fall asleep yet, papacito,” she murmured.

Love that night wasn’t about getting it over and pushing [her past, abusive husband’s] dead weight aside before he dozed off. This wasn’t to say that Lucinda and Ramón didn’t fall asleep right in the middle of everything. But it was a pleasant sleep. A siesta. And when they awoke early the next morning, they picked up where they’d left off. Ramón actually cared where those folds between her legs led, what they could do, that Lucinda felt something too, that the episode wasn’t over until she had produced a certain song in her chest.

“Mi amor,” Ramón said afterward.

A man of Ramón’s age didn’t have to finish any sooner than his woman wanted him to.

So, give your mom some condoms if you must, but remember: you weren’t found under a cabbage patch!

***

Check out Bonnie’s new collection, What Happened Here, available for purchase!

***

Bonnie ZoBell’s chapbook, The Whack-Job Girls was released by Monkey Puzzle Press in March 2013. She has received an NEA fellowship in fiction, the Capricorn Novel Award, A PEN Syndicated Fiction Award, the Los Angeles Review nominated one of her stories for a Pushcart Award, a place on Wigleaf’s Top 50, and a story published by Storyglossia was named as a notable story in story South’s Million Writers Award. After receiving an MFA from Columbia on fellowship, she has been teaching at San Diego Mesa College where she is a Creative Writing Coordinator.

Brent Armendinger’s SUMMER READS

As part of Summer Reads, Brent Armendinger shares what he’s looking forward to reading this summer.

***

American Canyon by Amarnath Ravva

Panorama as a sentence. Amarnath Ravva is a prose writer, a video artist, a photographer, and a performer. His experimental memoir, composed of text and documentary footage from California to South India, is a time-lapse photograph of ritual, longing and belonging.

Hemming the Water by Yona Harvey

I was entranced when I first heard these poems – Yona Harvey was not so much reading them, as she was singing them, or they were singing [through] her. Music of parable, mourning, protest, the body, and survival – daily life splits across the page and throat by all that is right and still very wrong in this world.

Gephyromania by TC Tolbert

In Territories of Folding, TC Tolbert, a genderqueer, feminist poet, describes “grafting an exegesis of skin,” proposing that the body is a text, a language that can only be understood through a continual process of layering. I love the tender, radical ways that Tolbert repositions parts of speech and inhabits the visual field of the page. I’m so excited to read this full collection, which Tolbert describes as being “written between who I loved and who was leaving, between who I was and who I would become.”

I’m OK, I’m Pig! by Kim Hyesoon, transl. Don Mee Choi

When I heard Don Mee Choi read from this terrific translation at AWP this year, I was blown away. A prominent South Korean feminist poet, Kim Hyesoon sets surrealism on fire, until it becomes as menacing as the various kinds of violence that inform her work.

The Albertine Workout by Anne Carson

Before she visited my class, Anne Carson asked us to come up with an exercise routine for someone who is always asleep. Then she read this brilliant series of 59 paragraphs on/for Albertine, the principal love interest in Á la recherche du temps perdu, who begins – through Carson as medium – to stare back from the dream in which Proust confined her.

***

Brent Armendinger is the author of The Ghost in Us Was Multiplying, a book of poems forthcoming from Noemi Press. He has also published two chapbooks, Archipelago and Undetectable, and his work has appeared in many journals, including Aufgabe, Bateau, Bloom, Bombay Gin, Colorado Review, Denver Quarterly, Hayden’s Ferry Review, LIT, Puerto del Sol, RECAPS Magazine, Volt, and Web Conjunctions. In 2013, Armendinger was a resident at the Headlands Center for the Arts. He teaches creative writing at Pitzer College and lives in Los Angeles.

June 4th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Catalog of ri¢h poets: Manuel Arturo Abreu

I usually write the introductions on my own posts around here, but Manuel Arturo Abreu’s intro is hella cute. And their post is hella cool and good and important. Sooooo /Tsaritsa out.

Poets stack that immaterial paper by living in the danger zone. Making written or typed marks is a way of briefly reminding ourselves we exist. It’s easy to forget when you’re rolling in the dough. The world is confusing when the spirit is so rich. This is why I say “you feel me?” Alexandra the based goth (aka Tsaritsa aka Billy Corgan’s Whore aka the version you were afraid to ask for) asked me for a poem for her Catalog of ri¢h poets and I sent her this one about changing the game.

VIRTUOSO

Mr. A and Mr. B had just graduated from the same college. Mr. A was a biology major and Mr. B was a physics major.

º

Mr. A felt the need to “change the game.” He vaguely knew about biometrics, and wanted to learn how to code, but felt like his “instincts had failed him,” that he’d discovered about Silicon Valley too late, or something, and should’ve started coding when he was ten, maybe. He would have been a virtuoso by now.

º

Mr. B wanted to become part of a startup. He was a quiet beast at coding. He remembered once when a white guy wrote in a notebook, after a conversation with him, “QUANTUM COMPUTING → $$$” and then said he had to go do something. He was carrying a purple yoga mat. He had said he had just finished rehab for “a bunch of dumb shit.”

º

Mr. B’s parents had visited recently from India. He felt “drastically changed” from the experience, and stopped smoking cannabis. He had not been back home to Tamil Nadu in two years. He felt aversion to the idea of returning, but only had three months to remain in the US after graduation before needing to find employment, before his “grace period” ran out. He tells Mr. A, “I’m an alien. That’s what they consider me, like the government you know.”

º

Mr. A remembers when one of his friends told him a story about “how I believed for way too long that ‘illegal alien’ meant actual aliens, like from outer space, and I was hateful and afraid, until when I was like nine I learned it just meant real people, who like, the government or other random people had decided weren’t allowed in this country, and I was like oh, that’s so evil.”

ABOUT THIS POEM

VIRTUOSO is a poem about being the best there ever was. Changing the game is a pressing concern to most people. Thus my poem is an example of Search Engine Optimization (SEO). The key is that both characters are my real-life friends. One is American, one is not. Therefore, because quantum computing, yoga, cannabis, and immigration issues are trending, I firmly believe this poem will soon become the first google search result for “i don’t understand why people have to work to stay alive why can’t we just walk around and talk and heal from history and stuff.” I worked as a personal assistant for a self-described ‘SEO wizard,’ I know what I’m doing. He also had two poodles. VIRTUOSO is from a chapbook called List of Consonants, forthcoming from Dig That Books.

manuel arturo abreu is a poet and forgone soul based in portland. They are from the Bronx so the epithet ‘boogie-down’ applies here if you need a reason to google ‘manuel arturo abreu.’ manuel likes emo sexts, jazzercising, and sketchy ecoqueer fantasias. Their ideal date is a group of people sharing a laptop to show each other music online. manuel is hard at work tweeting, editing at greybook , and sleeping things off. Hire them, email for more info hearingdeafone@gmail.com.

Cosplayers

Cosplayers

Cosplayers

by Dash Shaw

Fantagraphics, 2014

32 pages / $5 buy from Fantagraphics Books

Rating: 7.8

Dash Shaw’s other comics, especially 2010’s BodyWorld, push the boundaries of the comics medium in exciting ways, but they can also be daunting, especially to readers who are not comfortable knowing which panel to read when in a comic book—let alone be ready to turn the pages on their axis. However, Cosplayers is a much more accessible starting point in Shaw’s oeuvre. The one-shot does not play with form as much as Shaw’s other work, but it still showcases his lush color palette and his adventurous concepts.

June 3rd, 2014 / 12:00 pm

……Kevin Sampsell’s Paper Trumpets…..

***

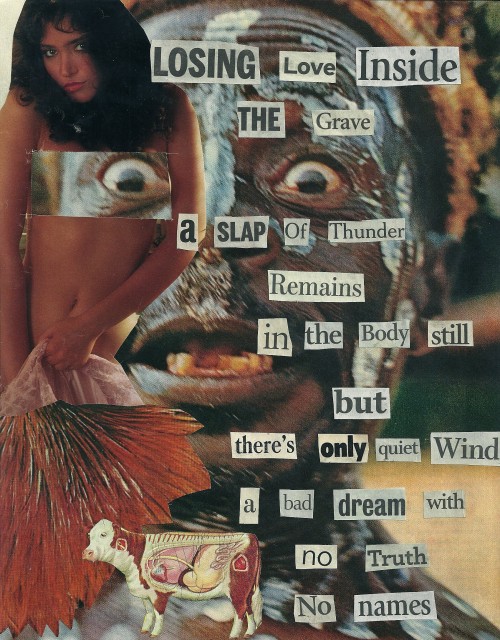

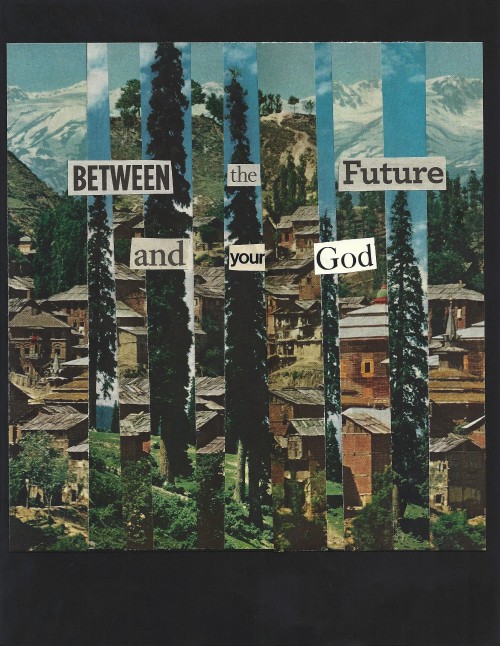

In late April I read with Kevin Sampsell and Jay Ponteri in Nathan Curtis Warner’s LYE:WORDS at Pond Gallery.

***

Kevin had a projector set up and interrupted reading from his book to show his Collages. Sometimes they contained text, and sometimes they didn’t. Sometimes Kevin read the Collage text. . .Regardless, I was quite taken by them. . .And so I asked Kevin if I could feature some of them here on htmlgiant.

***

What follows, then is a Q & A we did with Kevin’s Collages interspersed.

***

****

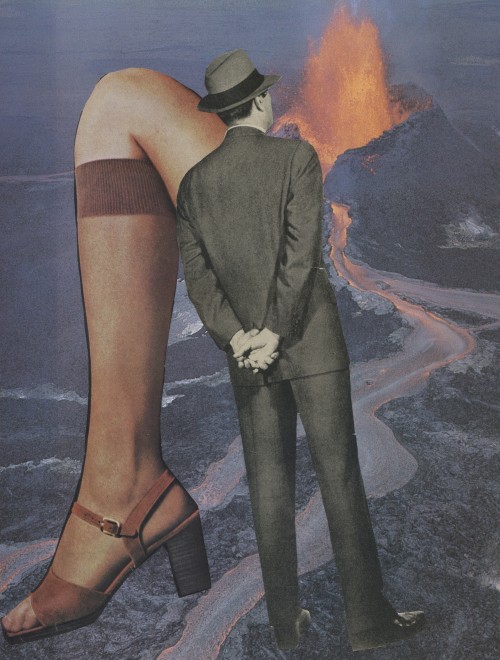

Rauan: How did you get started doing Collages ??

Kevin: I was inspired by the cut-up experiments of William S. Burroughs and actually started doing word collages, mostly from newspaper headlines, about twenty years ago. I put out a weird little chapbook called Children’s Book in 1996 and I’ve always wanted to make a follow-up book. I’ve kept this big manila envelope of words ever since then, occasionally pulling it out and making funny cards and pictures with them and giving them to friends. But those were more about wordplay and odd language. At the beginning of this year, I decided I’d pull out that envelope and start making more collages, kind of as a break from writing. I started to look around at other collage stuff on-line and discovered this whole big vibrant world of collage artists and, more importantly, I started to seriously consider the use of altered images to play off the words. I discovered this book called The Age of Collage and it included profiles and work by a bunch of great artists doing amazing work with collage. This page on the publisher’s web site included videos of John Stezaker and Linder Sterling and I became hooked. Stezaker’s video was especially influential. I started to look at collage every moment that I could and I joined a bunch of collage groups on Facebook too. I started to put more importance on how the images in the collage were presented. Words are still important, but the images are equally so now. Something clicked in my brain and I’m starting to figure out things with images. How to play with them and make them do strange things. Making collages is like creating optical illusions sometimes. Like with writing fiction or poems, pretty much anything can happen.

But those were more about wordplay and odd language. At the beginning of this year, I decided I’d pull out that envelope and start making more collages, kind of as a break from writing. I started to look around at other collage stuff on-line and discovered this whole big vibrant world of collage artists and, more importantly, I started to seriously consider the use of altered images to play off the words. I discovered this book called The Age of Collage and it included profiles and work by a bunch of great artists doing amazing work with collage. This page on the publisher’s web site included videos of John Stezaker and Linder Sterling and I became hooked. Stezaker’s video was especially influential. I started to look at collage every moment that I could and I joined a bunch of collage groups on Facebook too. I started to put more importance on how the images in the collage were presented. Words are still important, but the images are equally so now. Something clicked in my brain and I’m starting to figure out things with images. How to play with them and make them do strange things. Making collages is like creating optical illusions sometimes. Like with writing fiction or poems, pretty much anything can happen.

RK: Can you tell us a bit about yr Collage process??

For me, collage is all about seeing, as opposed to writing READ MORE >

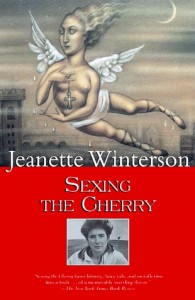

#jeanettewintersonlivetweet: Sexing the Cherry by Jeanette Winterson

Sexing the Cherry

Sexing the Cherry

by Jeanette Winterson

First Edition Bloomsbury, 1989. Grove Press Reissue, 1998.

192 pages / $14.95 Buy from Amazon

I just read a review of Sexing the Cherry online, through JSTOR. The article is written by Rosellen Brown, and is published in The Women’s Review of Books. It is called “Fertile Imagination.” Considering the content of the book, that title is funny to me. I’m honestly not sure if the review is favorable or not. She keeps praising the ‘inventive arbitrariness’ of the novel at the end of it, seemingly out of nowhere, somewhat condemns the thin veil over what she refers to as Jeanette Winterson’s ‘wish-fulfillment fantasies.’ That got me thinking about this sandwich I bought from Wawa earlier, and how when I was walking back to my house after buying it, I thought about how Jordan is very much like the titular character of Henry Fielding’s The History of Tom Jones. They are both foundlings, both of them are charismatic and somewhat sensitive; somehow my train of thought disappeared though, and my mind drifted from the process of it, like a moving vehicle. In this review I learned that Jeanette Winterson is herself a foundling, and much of her character is apparent in Jordan. Does this mean Jeanette Winterson is also like Tom Jones? By the transitive property, it would seem so. But does the transitive property define reality? I’m not sure, but if it were so, this would lead to a comparison of Tom Jones’s Squire Allworthy and Sexing’s Dog Woman, who, I feel, are not compatible characters at all. I am wondering what would happen if Allworthy and Dog Woman were in the same room. She is so used to men literally ‘pointing dicks’ at her, forcing/inciting her to violence against them. Allworthy is not that way at all, though. He is, I feel, one of the most benevolent of Fielding’s creation. Maybe he just lives in a more humanistic era than Dog Woman. The next paragraph is imminent; in it I will discuss what happened when I first read Sexing the Cherry.

I was on the third floor of a college library with Sexing the Cherry on my lap. I was tired. I wasn’t thrilled to be in the library, even though generally I like it there. I decided it would help me stay attentive if I ‘livetweeted’—that is, ‘to tweet in real time’ my process of reading it, by means of phrases that I found interesting maybe. I did this for around two hours. A list of things I found tweetable:

So, there is that. Looking at it now, it’s kind of like a poem. Some of the phrases are taken out of the contexts of the sentences they appear in, for my linguistic pleasure, and, I think, yours as well because you’re reading this. I mean, what is context really, especially considering the text of Sexing the Cherry, wherein there is no context given to the reader; through one’s own constructions/deconstructions/discursive formations/ideologies/psychoanalyses/feminist reconstructions only can meaning be derived from this book. The crux of this review, really, is being set up currently. I want to define something about this book—not make a guess as to what gender some fruit represents, or what is represented by the splitting of said fruit. Truly make a claim about what something in this novel ‘means.’ Here is my theory about Sexing the Cherry.

It is clear, from the outset, at least, if one reads the inscriptions before the text begins; those two things—the one about the Hopi tribe’s language lacking tenses for time and the other about matter being mostly empty space—that the universe is not as it seems. The one in the book, I mean. There is deliberate anachronism not only in the physical setting of the novel (I’m not usually one to judge, but Dog Woman and Jordan live in a pretty ‘temporally fucked’ part of 17th Century England) but in the way time is presented through language and the novel’s linguistic structures. Sexing the Cherry presents a universe in which time and space are not interwoven into our coveted, Einsteinian fabric; indeed, they are separate, and ever-colliding. These collisions are marked by pictures of fruits and, in the middle of the novel, fairy-like relics. As a result of the lack of connection between time and space, perspective is fluid; not how our universe’s perspective is fluid, in that a worldview can change through a human’s own will, but that dominance of perspective is constantly shifting. The rift between special coordination and the motion of things causes all consciousness to warp together, and the dominant perspective is in omnipresent shift. That is why every time there is a fruit somewhere, the narration seems to change and, towards the end the fruits are all split—this is an indicator of the unstable temporality becoming even more and more so. That’s pretty much my theory about why Sexing the Cherry is so weird, temporally and spatially speaking. On to another topic, I guess—

Now I am reading another JSTOR article about Sexing the Cherry, called “Innovation without Tears,” this one written by a man named Gary Krist. I think it’s a man. Regardless, it begins with the usual jab at postmodernism; I find that most reviews of apparently ‘postmodern’ texts begin with a jab at postmodernism. Everybody loves to hate postmodernism, it seems—so postmodern. After that, he writes about a book by someone who I always confuse with ‘Conan O’Brien,’ even though his name is ‘Tim O’Brien.’ Nevertheless, I find it interesting because I remember some friends from high school who, being in a more advanced English class than I was, were assigned to read a book called The Things They Carried. It’s about war and I was always glad I didn’t have to read it, but reading about it right now makes me want to read it because it sounds interesting. Eventually, the article somehow ends up at Sexing the Cherry, after talking about the ‘fluidity of time’ or something. Similarly to the review I read before I started to write this, it began by praising the exciting, ‘fantastic meaninglessness’ of the novel, though arguably, in this article, making more of a case for its psychological, sociological, and philosophical implications; but after that, just like before, the flaws of it are presented—humorously, I feel, in this article, with the essayist stating his reluctance to dig at the novel due to admiration, but still does so immediately—one by one, from the seeming fusion of narration towards the end to the novel-wide abuse and unfairness towards men (the first article I read actually contained a sly joke about genital mutilation). Although, at the conclusion of the section devoted to Sexing the Cherry, a statement about its essentiality to the realm of ‘unconventional fiction’ clears up any question about whether the review is positive or not.

Does any of this make sense so far? If so, does it make more sense than Sexing the Cherry? If not, does it make more sense than Sexing the Cherry? Everyone acts as though Sexing the Cherry is such a strange book, but nobody says so about Beloved, and I actually think they are narratively very similar. Many of Toni Morrison’s novels are incredibly unconventional, but are generally praised simply as masterworks of fiction—rarely does someone tell me they read a Toni Morrison book and thought it was ‘weird’ or that it ‘didn’t make sense.’ I would normally say, I think, this happens because Toni Morrison has a clear agenda on her hands; this becomes problematic though, considering the parallels between Jordan and Winterson herself, and her obvious schema as a post-gendered woman. This is all so confusing. I think that might have just been a gender pun. I couldn’t read Sexing the Cherry without wanting to draw little fruits everywhere and write an epic poem. It even made me want to write a book of ‘unconventional fiction.’ I have done none of these things in the recent past.

***

Ben Morgan is person who writes, runs an online press thing called ‘Thought Process‘ and takes pictures of trees. Currently, he has two collections of poetry published online, as well as pieces forthcoming in SMASHEDCAT and TheNewerYork. (Follow him on twitter @ben____morgan)

June 2nd, 2014 / 10:00 am

Amanda Ackerman’s SUMMER READS

As part of Summer Reads, Amanda Ackerman shares what she’s looking forward to reading this summer.

***

Taste

2 a person’s liking for particular flavors : this pudding is too sweet for my taste.

- a person’s tendency to like and dislike certain things : he found the aggressive competitiveness of the profession was not to his taste.

- ( taste for) a liking for or interest in (something) : have you lost your taste for fancy restaurants?

- the ability to discern what is of good quality or of a high aesthetic standard : she has awful taste in literature.

- conformity or failure to conform with generally held views concerning what is offensive or acceptable : that’s a joke in very bad taste.

These particular books were selected because I could get them from the Los Angeles Public Library. The city of Los Angeles experienced record-high temperatures this month and we will probably have a brutally hot summer The heat makes it very hard to think. These books are all short. I found them excellent and feel better for having read them (or being in the process of reading them).

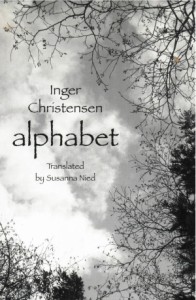

Inger Christensen’s alphabet, translated by Susanna Nied

This might be one of the best books I’ve ever read. Everything is in the world. The book is also written in a Fibonacci sequence, something I’ve wanted to try for awhile.

Excerpt:

“apricot trees exist, apricot trees exist”

Tan Lin’s insomnia and the aunt

This is the only Tan Lin book LAPL has. I have lived a good portion of my life watching television. Television is in and of the world and Tan Lin’s language becomes atmosphere, like a room enveloped in color and scent – living in and of the words becomes more important than their meaning as.

Excerpt:

“Any mathematician can tell you, lovers like drapes are feeble signs of a light that can’t come in, for the minute a TV show or a person becomes memorized (the worst form of recognition), it or she ceases to exist in any meaningful way. A dumb TV show is the most beautiful TV show. My aunt knew my love for her very well. She was clairvoyant and an insomniac.”

Alain Badiou’s In Praise of Love, with Nicolas Truong

The library doesn’t have this book. I like books that attempt theorizations of love and argue why we should radically love each other (two other good ones: bell hooks’s All About Love: New Visions and Erich Fromm’s The Art of Loving). Also, Badiou gives one of the first definitions of art that I find myself agreeing with.

Excerpt:

“One has to understand that love invents a different way of lasting in life That everyone’s existence, when tested by love, confronts a new way of experiencing time.”

Ann Quin’s Three

I’m only on page 22. It’s stunning. The dialogue is vulnerable, the poetry and prose cohabitate the story, and the vulnerable dialogue neither collapses nor widens the distance between its characters. Why it is we talk so much?

Excerpt:

“Hands motionless she gazed past the cockerel, marked a point between the trees, statues. The shadows of statues on the lawns stretched to cliff’s edge. What shall we do Ruth it is our last day fancy going out for a while? You’re so restless.”

Latasha N. Nevada Diggs’s TwERK

This book is brilliant. I’m only on page 15. I find myself sounding each word out loud. I like one of the blurbs: “an endlessly spinning polyglot wheel.”

Excerpt:

“It is said that eels can come back to life. Chopped into tidbits, left alone, the pieces may regenerate, wiggle; grow new heads, eyes. Teeth. The girl thinks of this every time she eats sushi. She never eats eel two days old. What if it came back to life and paid her a visit one shifty night?”

***

Amanda Ackerman is the author of the chapbooks The Seasons Cemented (Hex Presse), I Fell in Love with a Monster Truck (Insert Press Parrot #8), and Short Stones (Dancing Girl Press). She has co-authored Sin is to Celebration (House Press), the Gauss PDF UNFO Burns a Million Dollars, and the forthcoming novel Man’s Wars And Wickedness (Bon Aire Projects). She is co-publisher and co-editor of the press eohippus labs. She also writes collaboratively as part of the projects SAM OR SAMANTHA YAMS and UNFO. Her book The Book of Feral Flora is forthcoming from Les Figues press.

June 2nd, 2014 / 10:00 am

Laura Romeyn

What We Make of Her

Happy Meal Barbie wears two-inch heels.

Hair pulled up in a yellow pile and hands

on her hips in a swaggering way, I’m lighting

the match to her plastic narrows and then,

I’m lighting it again. Eyes grow wide as she begins

to flux, to soften, and blue is a sink in a pool

then it pours. Rereleasing my strike, I illumine

her pucker, replace kiss for a smear. In my mind

mopping away stains, blood lips from her face

like a plaster wall set to come down two weeks,

one week, now, followed by a bandaged attempt

at smoothing over. Features come back or don’t,

the way a house turned salon is still a house,

Nesquick and Fun Dip are still a diet, but not.

Barrettes, pinkpants and a big blonde bag puddle

to the side in their own shock and I let them,

body a fizz. Face cools, face hardens, and I take out

my Sharpie and I fix her myself.

Bio: Laura Romeyn is pursuing her MFA in poetry at Columbia University. A poem of hers most recently appeared in Leveler. She lives in Brooklyn and can be followed on twitter @LaRomage