Interview: Sally Delehant & Emily Pettit

Named after former professional basketball player and humanitarian extraordinaire Dikembe Mutombo, Dikembe Press is a newish micro-press out of Portland, Oregon and Lincoln, Nebraska that publishes things, most recently Matthew Rohrer’s poetry chapbook A Ship Loaded With Sequins Has Gone Down and Emily Pettit’s poetry chapbook Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something. In celebration of the latter title, the poet Sally Delehant—author of the collection A Real Time of It (The Cultural Society, 2012)—recently conducted an interview with Emily P. to discuss Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something and Emily’s notions regarding anxiety, the definition of the word “conundrum,” dollhouse furniture and the artwork of Bianca Stone (which is featured throughout Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something).

Named after former professional basketball player and humanitarian extraordinaire Dikembe Mutombo, Dikembe Press is a newish micro-press out of Portland, Oregon and Lincoln, Nebraska that publishes things, most recently Matthew Rohrer’s poetry chapbook A Ship Loaded With Sequins Has Gone Down and Emily Pettit’s poetry chapbook Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something. In celebration of the latter title, the poet Sally Delehant—author of the collection A Real Time of It (The Cultural Society, 2012)—recently conducted an interview with Emily P. to discuss Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something and Emily’s notions regarding anxiety, the definition of the word “conundrum,” dollhouse furniture and the artwork of Bianca Stone (which is featured throughout Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something).

Word is bond.

***

Sally Delehant: The title of the chapbook begins with the word “because” which positions the reader to assume a “why” question floats in the background of the text. I’m wondering what you think that question might be? Does it have to do with why we curl up to a specific person or part of our world? Or is the title perhaps an answer to the big question hanging above all of us — “Why write a poem?” Someone smarter than I am said in a poetry workshop once that on a basic level a poem works out or goes deeper into some kind of anxiety. Something is either resolved or agitated more. Do you agree? Do these poems work like that?

Emily Pettit: I think there are a number of questions that lead to this “because” and two questions in particular. One is — why are we behaving this way? The other is — why are we feeling this way? Two rather general seeming questions, until they are connected to specific ideas and feelings encountered in the poems. The question — why write a poem? — is a question and is a question that I can see these poems pointing people towards thinking about.

Emily Pettit: I think there are a number of questions that lead to this “because” and two questions in particular. One is — why are we behaving this way? The other is — why are we feeling this way? Two rather general seeming questions, until they are connected to specific ideas and feelings encountered in the poems. The question — why write a poem? — is a question and is a question that I can see these poems pointing people towards thinking about.

In response to your mention of poems being ways that one might work through or with anxiety, I think poems are often working in this way, being asked to work in this way. In regards to my poems, I’m hesitant to use the word “anxiety” because I feel like I use that word all the time in conversations I have with other people and myself and that its meaning is not containing what I want it to communicate. Or various things the word “anxiety” communicates, I worry negate or dim the things in poems that I’m looking for as a reader and looking to make happen as a writer. A friend recently shared with me the following Borges line, “The metaphysicians of Talon are not looking for truth, nor even an approximation of it; they are after a kind of amazement.” In poems I am looking for amazement rather than truth or an approximation of truth. For me amazement might be experienced through encountering two words, the juxtaposition of which make music to my ear or a striking image to my eye. I am looking to be amazed by a feeling that arises when I encounter the ideas, images and music that I encounter in poems. Why I write poems is to find these things that I am also looking for as reader. Anxiety is everywhere, but something I love about poems is that a poem is a place where I do not need to name anxiety, should I not want to. Naming things can give things power or an agency of sorts and the effects of naming things can be good or bad depending on too many factors for me to list here. Poems are a place where I feel I have control over what my brain and heart give agency to. And to a certain extent I have control over the effects this agency has. I have not found many places outside of writing where I get to experience this sort of control. In the poems in this chapbook there are ideas about anxiety and ideas about ideas about anxiety, but they are existing alongside often adamant ideas that anxiety can be controlled and sometimes productively ignored and denied. What it is taking me a long time to say is, I like how my imagination deals with anxiety more than the way other parts of me deal with it.

Sally Delehant

SD: In the first poem in Because You Can Have This Idea About Being Afraid Of Something you write, “I freak out, freak out, freak out, / with a quiet mouth,” and as I trace the freak out through the poem (and chapbook) there seems to be tension between doing/being what one naturally does/is and what one could/should do and be if that makes sense. You can wear a nametag that says Emily or rabbit and in another sense be the “best refrigerator ever” as well as many other things. What I’m clumsily getting around to on this sleepy, Sunday afternoon is that I think part of our humanity tells us we should should should be a certain way and we fear we might be “the most ridiculous person (we) know” as you write later. The most beautiful and comforting thing we can hear is that we are good dogs. The speaker “wants to be a good animal.” She wants to let us know that we “are exactly where we are supposed to be.”

Are there things that make you think you aren’t where you are supposed to be? Without being intrusive I want to ask you one thing that scares you, and then I promise we can talk about the beautiful drawings in the book which I am curious about too. What is a thing you are afraid of, Emily?

EP: I’m afraid me talking about fear outside of poems is like encountering a black hole. A hall of mirrors. My brain is exhausting in this way. I’m afraid that outside of my poems I fail to be funny about fear in the way that I want to be. I like that in poems I can feel funny about fear. I think anxiety and fear are absolutely linked. I have never encountered a definition of anxiety that does not use the word fear as a part of that definition. I like that when I’m dealing with fear in my poems, while writing poems, I do not feel anxious. Or if I am feeling something that could be defined as anxiety or fear, I’m not aware of it, or not naming it.

I think the thing that both my poems and my answer to your first question point to is a fear of both the presence and absence of control. It’s a conundrum. And I say conundrum, because I don’t think of a conundrum as hopeless. I like how in language with one word, conundrum, you can communicate a subject and a tone. For example, if you had asked me “What is a thing you are afraid of?” versus “What is a thing you are afraid of, Emily?”, to me the first question feels much less scary than the second question. Naming me has given me a louder agency, more loudly bonding me to whatever answer I answer. One word. A word. A name. For me to explore fear or ideas of fear in a poem is a place that I am not as afraid of exploration. Exploration feels not just possible but exciting. In conversation and in prose (like writing this now) I have trouble with this exploration; I feel accountable to ideas leading to resolutions of sorts, resolutions that very possibly do not exist. Resolutions of logic that are not expected in poems. Or are not expected by me in relationship to what I think of as a poem. I’m afraid of many things. I’m very appreciative of a poem being a place where I can have some control over my fears and how they feel to my brain and my heart and my body. I’m very appreciative for getting to write poems and read the poems of others for the ways in which this engagement allows me to escape my fears.

THE PERENNIAL AMBIGUITY OF CHRISTOPHER WOOL

I like Christopher Wool’s artwork. Wool became famous for his paintings of strong, provocative phrases in black letters, primarily ALL CAPS. Wool’s works are of an abstract nature, sometimes intricate in presenting an idea, other times arcanely elusive. In October’s Vogue Dodie Kazanjian scored a rare interview with the media-reclusive artist. The format and presentation of the arguments the writer provides to the text more closely resembles that of an essay, but many intriguing themes come up.

By introducing Willem de Kooning’s approach to artistic work–who worked “out of doubt”–as a starting point, the writer reveals the artistic intentions of Wool to be consistent in their omnipresent questioning and doubting. They are works defined by what Kazanjian calls a “perennial ambiguity.” This ambiguity may also be viewed as the proclamation of the honest confusion of an artist. Thus, the refusal of adopting an authoritative style should not be considered the result of limited intellectual rigor, but rather should be respected for its humility.

Discussing his artistic aspirations and how he managed to become a significant part of the modern art world, Wool asserts that his path was somewhat coincidental. “It just kind of happened,” he states. A key to his success was possibly that his early years in New York coincided with a legendary era of NY nightlife and culture: CBGB and Max’s Kansas City. The intersection of nightlife and the art-reality that was being created was evident in the 1980s, and shaped the public’s perception of artists’ role.

Upon revisiting his old work, the artist himself confesses: “They were offensive, funny, and indelible–you had to pay attention.” Consequently, it is not surprising that the critical response to his work varied. Some thought it populist in its negativity, while others observed in it a radical stance: a cacophonous harmony, or a refreshing pathos. What is predictable in his work is Wool’s lack of “conclusiveness” or the absence of artistic closure.

“I firmly believe it’s not the medium that’s important, it’s what you do with it,” the artist clarifies.

……No More Sentence(s)……

***

The forthcoming, and 10th, issue of “Sentence: A Journal of Prose Poetics” will be the last. Yes, of course, just like people are born and die, journals come and go:

And yet— And yet—

Sentence is where I discovered poems and poets that changed the way I wrote: poems and poets (dead and alive, American and otherwise) that changed the way I thought about Poetry and its possibilities. Furthermore, Brian Clements, one of the founders and long-time editor of Sentence, was my first and best mentor when I began writing again (and for real) in Dallas in the late 1990’s.

***

So, to follow is a little Q & A that I just did with Brian which, among other things, looks back a bit over Sentence’s excellent 10 year run :

(note: back issues, except 1 and 2, are still available)

And yet— And yet—

***

Rauan: The Prose Poem seems to be in a much better place than it was when you started Sentence in 2003? I mean that now it seems Prose Poems are welcome and present just about anywhere. Is this part of the reason you’ve decided to stop?

Brian: I don’t know if the prose poem is in a better place; it’s in a different place READ MORE >

Interview with Angela Leroux-Lindsey of The Adirondack Review

I’ve always been curious about the darkroom where literary magazines come together. This is a series of interviews engaging, talking, and sometimes annoying editors about their magazines. How did they come about, what do they hate about editing, and what do they love most about it? This is the first in the series and I talked with Angela Leroux-Lindsey of The Adirondack Review. The visual imagery is simply stunning. The Adirondack Review is like an art gallery curated online, constantly evolving, fused together with great stories, poetry, and essays. In preparation for the interview, I pretty much went through the entire archives and got a brain dump, Matrix-style, in art and photography. A jolt to the system is what I like feeling with my lit magazines and reading directly from their about page: “The Adirondack Review is an independent online quarterly magazine of literature and the arts dedicated to publishing poetry, fiction, artwork, and photography, as well as interviews, articles, book reviews, and translations. Recently named a ‘great online literary magazine’ by Esquire and a ‘top online journal’ by The Huffington Post, TAR was established in the spring of 2000, with its first issue appearing that summer.”

As a brief bio and introduction to Angela Leroux-Lindsey:

Angela Leroux-Lindsey is editor of The Adirondack Review and senior editor with Black Lawrence Press. She writes for Kirkus Reviews and A&U Magazine, and has contributed essays and stories to phys.org, Animal Farm, Innovation Magazine, NY Metro, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and others. She lives in Brooklyn.

***

PTL: Can you tell us about the review, how did The Adirondack Review first get its inception and how did you first get involved?

Angela Leroux-Lindsey: The magazine has actually been around since the summer of 2000—the founder editor, Colleen Ryor, was sort of a pioneer in never going to print, which is something I’ve always admired. But I didn’t start contributing until 2006 or 2007. At that point Diane Goettel was editing, and when she left to run Black Lawrence Press full-time, I took over. So my first issue was in the winter of 2009. A big part of the appeal was their early commitment to publishing art. I especially love how being online gives us the freedom to publish as much full-color art as we want; in the fall issue, I featured almost 30 images by five different artists and photographers. This is something we could never afford if we had to pay for ink and paper. We also publish poetry, fiction, and works in translation in every issue, a mix of mediums that I think is really lovely. Every time we close I’m sort of delighted to see unexpected threads emerge that tie completely different submissions together: a drawing that evokes the tension of post-apocalyptic familial relationships next to a story that takes place on a placid lake over the course of an afternoon but is really about survival. Discovering these entanglements and bringing so many different people together is so much fun. It’s the best job.

PTL: Each issue is packed with fiction, poetry, and some of the most incredible photography and art I’ve seen. What goes into the curating and selection process?

ALL: Well, like every small lit mag out there, I rely so much on my staff. We all volunteer, which makes it even more amazing that I’ve found a group of people willing to be so thoughtful and imaginative about how we compose issues. Nick Samaras, our poetry editor, came on board when I did and he’s brilliant. Google him, read his poetry, you’ll just swoon over it.

Regarding art, some of it comes in through the submission process, but a lot of it I solicit. Sometimes I’m just scrolling through tumblr and come across a piece that floors me. And I’m always completely thrilled when a big name that I’ve solicited says yes: I mean, Manfred Mohr was on the cover of the summer issue. I was watching some of his animated videos from the 70s on YouTube, and figured I’d send him an email to ask if he’d be interested in featuring some of his new stuff. And he emailed me back within a week and said yes. I’m still excited every time this happens. It’s magical. Richard Mosse is another example. I’m in love with his INFRA series, which is online now.

Really, getting to work with all of these artists and writers is absolutely the best part of having this role. Not just meeting new people and developing friendships—like with you, Peter—which I really value. But living in Brooklyn and getting to hang out with so many writers I admire is killer. You wouldn’t believe the people I’ve met and fallen completely to pieces in front of. I hosted a reading once with Paul Muldoon and could hardly pronounce my own name when I introduced myself. And then to watch emerging writers and artists who have published work with us go on to publish books or exhibit work at major galleries or museums is really awesome. My friend Kit Frick has a completely gorgeous chapbook coming out called Echo, Echo, Light from Slope Editions. We published early versions of a few of these poems in 2011 and I can’t wait to see how they’re incorporated into a collection. And Luba Lukova, a political artist whose work I sought out for the cover of the first issue I edited, will show at MoMA next month. Revisiting these issues and experiencing that kind of folding of time is a cool thing. It makes me think of the larger view of independent publishing as a sort of performance art space in itself.

…….I am Paulina……

Lying in bed the other day and listening to Paulina Rubio’s sultry and filthy voice I felt suddenly (no, I knew!) that I could have written her songs and that she could have written my poems.

——Encrusted W/ Emeralds——Stinking Ditched——Boiling——

——I’m On The Back——Of An Elephant READ MORE >

September 24th, 2013 / 10:36 pm

An Open Letter to Readers and Writers on the Internet Regarding the Founding of El Aleph Press

Dear Internet Readers,

You know that boringly recurrent conversation in which someone laments the end of print and someone else talks about how craftsmanship, design, and embracing new media can actually make small presses more viable and exciting than ever? In that conversation you are the second (more optimistic) person. Or at least you like to hold out hope that that person’s correct. And because of that you really should know about El Aleph Press.

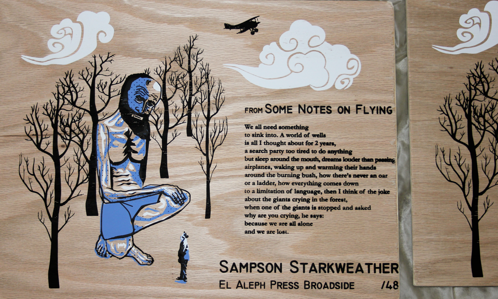

In the interest full disclosure and as proof that I know what I’m talking about, I should say that I’ve known and been friends with El Aleph’s founder/editor, Michael Bagwell, for several years. I like him, I trust his aesthetic. So naturally I was excited to hear that he’d started a press. Then I actually got my hands on the things he was doing and got even more excited. El Aleph makes books, broadsides, t-shirts, and now an anthology. Their website features writing, of course, but also short films and, soon, a whole host of other multimedia work. They’re getting involved in a lot of projects across a range of media, and everything they touch is beautiful and careful and medium-specific.

Let me give two examples of the work El Aleph is putting out. Their first broadside features a short Sampson Starkweather poem with a color illustration printed gorgeously onto solid wood. Their first book, Or Else They are Trees, is a collaboration between Bagwell and the artist Rebecca Miller. It’s similarly gorgeous, a mix of poems and full-color artwork. If there’s an early hallmark of El Aleph’s work it’s that language and design are equally meticulous.

I should also mention that El Aleph is currently looking for submissions for their forthcoming anthology. From what they’ve published and what I know of Bagwell’s aesthetic, you’d be well served to send in formally adventurous works, lyrical weirdness, and texts that are equally surreal and sincere. You should also send reviews, comics and more traditional stories/poems.

All of the information on El Aleph, their projects, and submissions guidelines are available at their website. So check out/submit/support, etc.

Very Best,

Ben

September 24th, 2013 / 11:00 am

….even if you don’t help them give birth to Lenses (“a messy, caustic bunch. Inherently unclean, fibrillating, picking, shifting in and out of dark rooms”) you should definitely check out Jake and Barrett’s creepy, unnerving video

(click here)

Stories Keep Us Warm: How an innovative reading series is firing up the Seattle literary scene

I was recently chosen to perform my story “Trigger” for The Furnace, a Seattle series where one prose writer is invited to read a single piece to completion. The writer performs their piece in front of a live audience, which is simultaneously broadcast over Hollow Earth Radio. By focusing on one writer (rather than several brief readings by multiple people), the series takes a risk in that it really relies on that single person to create a compelling performance and single-handedly drive attendance. What results from that risk is an always interesting, kinda weird, and truly unique listening experience. It also provides a beautiful showcase for the writer and their work, giving them a chance to explore alternative presentation styles—using actors, live musicians, sound effects and other elements to enrich the reading. With its radio broadcast, the series taps into older forms of storytelling by bringing people together to listen, either online or in person (herding us literary cats, in a way). From The Furnace mission statement: “Stories were told around a fire. They kept us warm and created a sense of connection and community.”

It’s really a kind of magical experience to both listen and perform at The Furnace. The Hollow Earth Space is small, but reads as warm and intimate, rather than cramped. And, as a reader, it was cool to know people were listening over the airwaves—friends of mine texted after the reading was done, congratulating me. There have only been five performances so far (which you can listen to on Soundcloud and The Furnace website), but the series has already gained a big following, and been a featured event in the local alternative weekly The Stranger many times. It’s been cool to see a relatively small, but pretty original idea build its audience and reputation in such a short amount of time.

To learn more about how the series got started, and what goes into putting it together, I had a little Q&A with the founder, Corinne Manning. Here’s our conversation:

***

LJH: So can you tell me more about what inspired you to start the series?

CM: As a prose writer it’s often tricky to participate in readings because I’ll have about ten minutes and that means usually cutting a story down, or just reading the first bit–where as ten minutes for a poet means something very different. I wanted to create a series that gave a prose writer the opportunity to read a piece all of the way through, and even get to explore presenting it in innovative ways. The chapbook that’s made for each event and the fact that its broadcast on Hollow Earth Radio is all part of trying to make a disparate literary community feel more cohesive, create a holistic listening experience for the audience member, and also give a writer a real chance to be showcased beyond the ephemeral reading.

LJH: How happy have you been with it so far? Have there been any challenges?

CM: I ran a series with multiple readers before (Other Means in Brooklyn, NY), and though I loved the format of that series and the intention, I’m much happier with the Furnace. There are some really obvious ways in which it’s easier than what I was doing before: it’s quarterly, there’s only one writer to schedule, and because that writer gets showcased in a really special way they take it seriously in a way that I hadn’t witnessed before. My co-coordinator Anca Szilagyi and I have always been lucky to get a really good crowd, which is really exciting because we purposefully try to showcase people who are emerging or who aren’t one of the same eight or so people featuring again and again.

LJH: Thinking more about readings, I’m wondering if you could describe the qualities that you think makes for a great listener experience. Like what makes you go: “Wow, I’m really glad I went to that.”

CM: This is like defining the mystery of the universe! There’s an essay by Frank Conroy where he talks about the relationship between the writer and the reader in a piece of fiction as this collaboration, where both the writer and the reader are putting a certain kind of energy in to make the story happen. The writer, he says, has to put in a little extra work to create space for the reader’s energy to fill the story. Esoteric, I know but I think the same thing happens at a reading. The writer who is performing is engaged in the act of telling the story—and is in a sense performing it. The listeners then too, should want to be there, are more engaged in receiving than just waiting for their friend to be the one who comes up on stage.

September 20th, 2013 / 11:00 am

First Study for a Long Walk: Castle to Castle

Lynn Xu and I are married, and we’re also poets. For the past year we’ve lived in an interdisciplinary residency in Germany, in a community of artists and all sorts of people we don’t usually get to hang out with: architects, new music composers, choreographers, filmmakers, even a chess Grand Master and a video game sociologist. Soon we will return to the States and to the small vacant lot in West Texas that we call our home. In order to continue conversations we’re having, and to drag art further into our life together, we’ve come up with a project called Architecture for Travelers. At its center is a collaboration with our friend Alan Worn, with whom we’re designing a house and a cottage where we can host residencies for creative people. There will also be poetry, photography, and a long journey involved. We’re not crowd-funding, but we are taking pre-orders for limited-edition photographs and books to help out with expenses. ( For more detailed info, visit our website.)

Beginning in November, I’ll spend a month or so walking 700 miles from my birthplace on Galveston Island to our property on Galveston Street in Marfa, sometimes accompanied by family and friends. Today Lynn and I went on a practice walk, and for the first time incorporated another aspect of the planned trip across Texas: taking photographs each hour on the hour (5 today, about 240 in Texas). We set out from our studio at the Akademie Schloss Solitude and four hours later arrived at Schloss Ludwigsburg. This is the second time I’ve traveled between these two castles on foot, the first was this past winter with friend, collaborator, and artist Charlotte Moth. Robert Walser wrote “A walk is always filled with significant phenomena, which are valuable to see and feel,” and both trips from Schloss to Schloss have lived up to this proclamation. During the first some of our ideas were dreamed up, and this time some details became clearer. Here are the five photographs from today’s walk, along with written sketches about our time on the road.

***

1.

We left at eleven this morning. Heading down the big hill Schloss Solitude sits atop, we could see the straight-as-an-arrow path we’d be following stretched out for six or seven miles, after which it disappears over a wooded hill. I turned around and photographed our starting point. It made me think of Wallace Stevens’s “Anecdote of the Jar”: “It made the slovenly wilderness / Surround that hill.” Despite a forecast of showers, the weather was perfect and the skies were blue and clear all day long.

2.

At the one-hour mark we were crossing through the outskirts of Stuttgart. There was some interesting architecture to be seen, but as the clock tolled the best thing around was a tree that Lynn spotted in a front yard behind a white picket fence. It was terrifying. It looked both totally out of place and too perfect for the suburban landscape. As we walked on, we talked about the best way to display the 240 photographs that we’ll have at the end of the Texas journey.