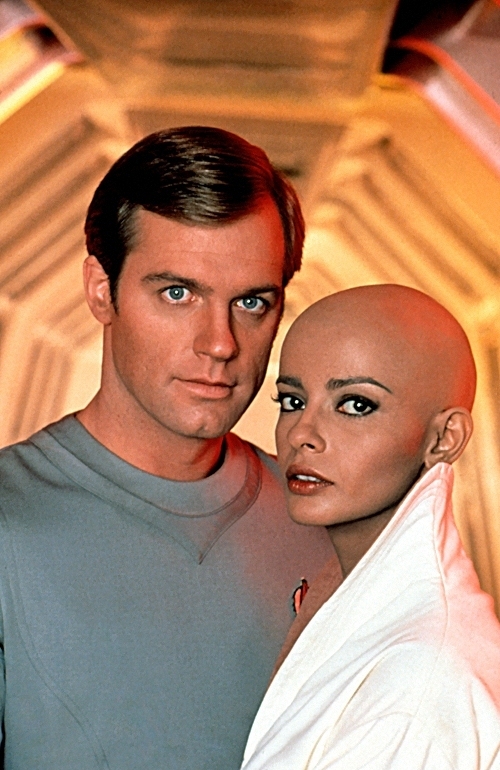

Another way to generate text #5: “synonym clusters”

This one’s easier to do than the dictionary clusters, but similar in principle. First, you look up a word in a thesaurus and collect every synonym for it. Then you write through that cluster of words.

Let’s try it with “bald.” Synonyms include:

bald, baldheaded, bare, bare-bones, bareskinned, barren, bleak, clean, denuded, depilated, disrobed, divested, dour, exposed, glabrous, hairless, head, in one’s birthday suit, naked, nude, peeled, plain, primitive, rustic, severe, shaven, shorn, simple, skin head, smooth, spare, spartan, stark, stripped, subdued, unadorned, unclad, unclothed, uncovered, undressed, unembellished, unrobed, vanilla

(To get this list, I copied the first three entries at Thesaurus.com into Notepad, then deleted all the extra text, then arranged the synonyms alphabetically in Excel, then deleted all the duplicate entries.)

Now let’s write something with that:

I slept with a bald woman once.

Repetition as rule, repetition as defamiliarization,and repetition as deceleration

As promised, back to Shklovsky! In Part 1, we examined his fundamental concepts of device and defamiliarization. In Part 2, we saw how context and history deepen what defamiliarization means. (That’s what led us to take our New Sincerist detour.) Now, in this third part, let’s return to Chapter 2 of Theory of Prose, where Viktor Shklovsky discusses “special rules of plot formation.”

Here it’ll be useful to remember that one of the meanings of rule’s root, regula, is “pattern.” Because Shklovsky is talking less about “rule of law” than he is about the patterns that devices combine to make.

Whenever you write—and it doesn’t matter whether you’re me or Chris Higgs or Mike Kitchell or Kathy Acker or Georges Bataille or whomever—you’re working with conventions. None of us invented these words, nor words, nor their spellings, nor syntax, nor sentences, nor punctuation. We didn’t invent writing. Nor did we invent literary criticism, or essaying, or blogging, or the HTTP protocol that transmitted this post to your computer. We’re all working within overlapping systems that, by virtue of the accident of birth, we find ourselves in. This should cause us no distress because rather than stifle our creativity or inhibit our originality, these systems and their rules provide the very basis for originality and creativity. Without any patterns or conventions we would be left with only noise, in which no innovation whatsoever is perceptible or even possible. It is in fact patterns and conventions that provide the opportunities for disruption and deviation.

In Chapter 2, Shklovsky is trying to understand patterns that authors use when stringing devices together. He isn’t interested in defining every pattern; nor is he interested in critically evaluating them (e.g., “this pattern’s better than that one”). Rather, he wants to examine commonly used ones and demonstrate (the following point is crucial) how even though the patterns are simple and common and predictable, they provide practically infinite opportunity for defamiliarization—and therefore artistry.

In the rest of this post I’ll focus on the simplest of those rules, repetition, with examples taken from Nirvana, Weezer, and Tao Lin.

23 brief replies to Blake Butler & Elisa Gabbert & Johannes Göransson & Chris Higgs re: (dear god, what else?) the fucking New Fucking Sincerity

ToBS R∞: Arguing in blog posts and on Facebook about aesthetics vs. Going out for a pleasant dinner together, then taking a nice walk at sunset in a park

I’ve decided that, from now on, all I’m going to write about at this goddamned site is this goddamned thing.

… No, seriously, I’m delighted that so many have chimed in. Thanks to everyone! I thought one massive reply would be easiest. If you read this whole thing, may your god shower blessings upon you. And if I missed any pertinent responses, kindly direct me to them in the comments. (I was traveling last weekend, and as such had trouble keeping up with all the discussion.)

1.

I’ve claimed (here, here, here) that one thing at stake in the New Sincerity is the discovery of what maneuvers currently count as “feeling sincere.” That such maneuvers exist I consider more an observation than a topic for debate. E.g., Blake, in his recent post about Marie Calloway’s Google doc pieces, wrote that Calloway’s recent work:

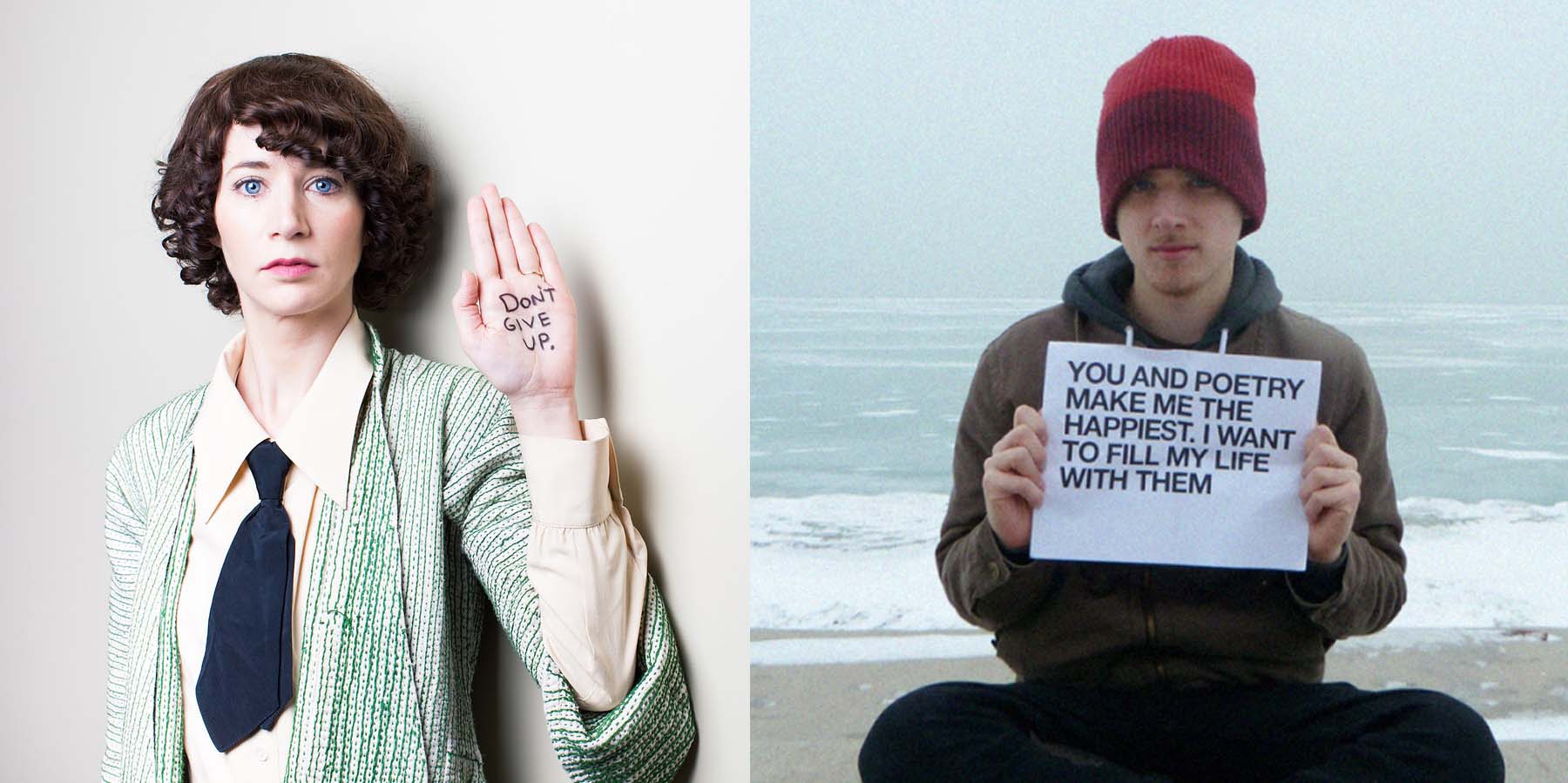

Masha Tupitsyn Do The New Sincerity In Different Voices

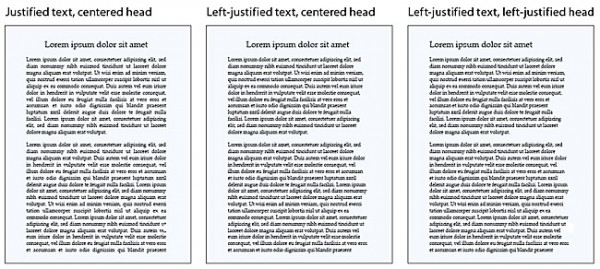

Notes on Design: In Praise of Ragged Edges

I am a largely self-trained book designer. I hope to someday have the time to take formal courses in design, but for now I do my learning by studying the books I read. This means that often I will come across a convention in book design that I simply do not understand. These conventions are not universal, but they are common. Indie and major presses seem to agree, for instance, that text should be blocky. In fact, the text of this website is mostly blocky.

What I am talking about is justification. At some point, nearly all the book designers in the US got together and decided that the proper alignment for prose was left-justified. What does a left-justified paragraph look like? Well you are reading one now. The left edge of the paragraph is aligned with the left margin, and the right edge of the paragraph is aligned with the right margin. The last line of the paragraph breaks this rule, because it would require extreme distortion of the text to ensure it met the right edge (the last line might be, after all, just one word long, and we don’t want to see that stretched all the way from left to right). But here’s the thing: essentially every line has to be distorted at least a little to make the edges match up right, and once you see this, it can be very hard to un-see it. The spaces between words and individual characters swell and shrink according to the needs of the line. You may find yourself struggling to read an especially crowded line; you may find yourself wondering why the spaces between the letters in the word “between” are so big. Words that disrupt the shape of the text too much become hyphenated in order to stop them from causing trouble. Sometimes they even split across two facing pages. Sometimes this is not disruptive. But sometimes it gets very ugly. READ MORE >

What we talk about when we talk about the New Sincerity, part 2

"Hi, How Are You?" cover art by Daniel Johnston (1983); "financially desperate tree doing a 'quadruple kickflip' off a cliff into a 5000+ foot gorge to retain its nike, fritos, and redbull sponsorships " by Tao Lin (2010)

It made me very happy to read the various responses to Part 1, posted last Monday. Today I want to continue this brief digression into asking what, if anything, the New Sincerity was, as well as what, if anything, it currently is. (Next Monday I’ll return to reading Viktor Shklovsky’s Theory of Prose and applying it to contemporary writing.)

Last time I talked about 2005–8, but what was the New Sincerity before Massey/Robinson/Mister? (And does that matter?) Others have pointed out that something much like the movement can be traced back to David Foster Wallace’s 1993 Review of Contemporary Fiction essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” (here’s a PDF copy). I can recall conversations, 2000–3, with classmates at ISU (where DFW taught and a number of us worked for RCF/Dalkey) about “the death of irony” and “the death of Postmodernism” and a possible “return to sincerity.” Today, even the Wikipedia article on the NS also makes that connection:

Another way to generate text #4: “dictionary clusters”

First, we pick a random word from the dictionary. Let’s go with “narwhal.”

First, we pick a random word from the dictionary. Let’s go with “narwhal.”

NAR·WHAL: noun. a small arctic whale, Monodon monoceros, the male of which has a long, spirally twisted tusk extending forward from the upper jaw. Also, nar·wal, nar·whale. Origin: 1650–60; < Scandinavian; compare Norwegian, Swedish, Danish nar (h) val, reshaped from Old Norse nāhvalr, equivalent to nār corpse + hvalr whale1 ; allegedly so called because its skin resembles that of a human corpse

We now list all the unique words:

arctic, corpse, Danish, extending, forward, corpse, jaw, long, male, Monodon monoceros, Norwegian, resembles, Scandinavian, skin, small, spirally, Swedish, tusk, twisted, upper whale

… then look up each one. This does take some time, and generates a lot of text, but it’s also educational and (I think) fun: