Pina (Bausch) The Movie — Cults and Transcendence (??) — Selling Out (??)

*******

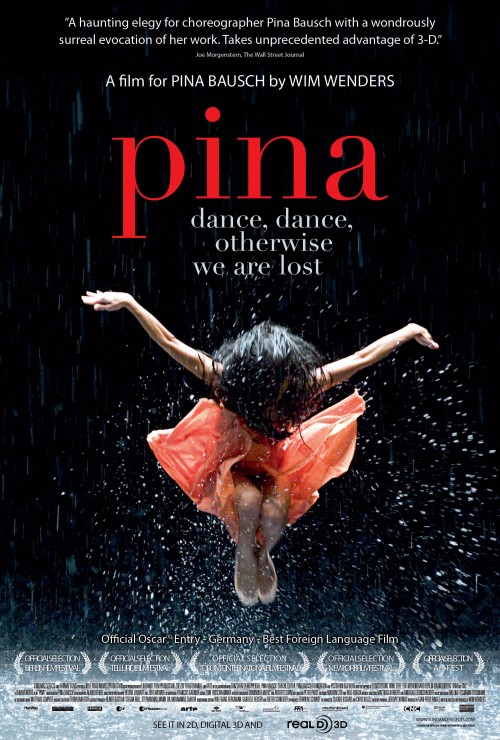

Pina, the movie, Wim Wenders’ movie, about Pina Bausch, the German dancer and choreographer, is a beautiful and strange thing about which much has been said– and I’m going, here, to put my 2 cents into the conversation regarding the inhumanity of the “characters” in the performances; the heavily-emphasized “cult” aspect of Pina and her dancer/followers; and, lastly, the fact that the movie, for all its strangeness, all its ability to jar, alienate and electrify seems to be a tamer and lesser version of what it could have been.

(It’s worth noting, also, that Pina died, unexpectedly, two days before production was set to have begun). READ MORE >

“HIS LAST DAYS AS AN ARTIST”

“HIS LAST DAYS

AS AN ARTIST”

Slash Lovering

60 min

[2011, partial, unpublished bootleg – Erik Stinson, 2013]

Characters

CARL – male, 29

LINDA – female, 24

ROMAN – male, 29, work friend of Carl

SOPHIE – female, 22, a reveler

1 EXT Bushwick, Monday night, in the quiet of the early

work week, walking from the train, then INT at CARL’s

apartment.

THE ACT OF MEMORY, “LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD” & THE THING OF INTENTION

SUBJECTIVITY OF MEMORY

Suzanne Corkin’s book Permanent Present Tense: The Man with No Memory, and What He Taught the World chronicles the fascinating case of Henry Molaison. Upon receiving a catastrophic lobotomy at the age of 27, Molaison continued his life as an individual incapable of forming new memories. For the remaining 55 years of his life, Molaison was closely studied by Corkin: his unique tragic circumstances constituted him as a one of a kind empirical specimen of anterograde amnesia, the medical term for his inability of forming new memories. Corkin found in him the ideal means to gain a deeper scientific understanding in the field of neuroscience[1].

Unlike the Drew Barrymore character in 50 First Dates, Molaison spent his amnesic reality in the company of a meticulous observer and not the romantic goofiness of Adam Sandler. The focus of Corkin’s book is the scientific exploration of how new memories are cerebrally processed. Corkin observed the short-span consciousness of Molaison’s new memories along with the variation of the feelings and thoughts he exhibited, as everyday provided a new opportunity to reassess her specimen all over, evaluate and reevaluate the pertinent data. Despite the repetitive occurrence of the same questions within his short-span of memory, Molaison’s responses were sometimes indicative of the formation of new memories. This analysis served as a catalyst for a new neuroscientific theory: contrary to previous popular belief that memories “were indelible snapshots of sense experience, stored in chronological sequence like the frames of a celluloid film,” memories are actually located in more than one location in our brains.

Mike Jay’s exceptional review of Corkin’s book[2], aptly entitled “Argument with Myself,” starts with a powerful definition of memory. Jay concedes that memory shapes one’s identity, but he argues that in addition it simultaneously functions as the (mis)apprehension of a well-founded, whole self: “memory is not a thing but an act that alters and rearranges even as it retrieves.” In this framework, it is evident that the way we conceive our individual realities, as they are constructed by all the memories we hold, are suspect. The manner in which all of us accentuate the details of what happens, both to us and in the world surrounding us is marked by subjectivity. While the degrees of each person’s paranoia and tendency for narrative exaggeration vary, there is no doubt that in most “realities” much is not real.

In an endeavor to make her students grasp this very fact, Mary Karr once began teaching a creative writing course by performing getting in a huge spat with the educational institution’s program director[3]. Once the program director exited, Karr revealed to her students the argument they had witnessed was a simulation. She then asked them to write down their observations and perception of the incident. The students had an arduous time reaching consensus on a collectively agreed objective account of what had just happened in their classroom. This exercise swiftly presents the validity of the very ambivalent nature of objective memories.

The Family Project by Julie Sokolow

– – –

Julie Sokolow is a musician, filmmaker, and writer whose work has been acclaimed by Pitchfork, The Washington Post, and Wire, among others. She’s a 2012 recipient of a Creative Development Grant from The Pittsburgh Foundation towards her first feature-length documentary, Aspie Seeks Love, about an Aspergerian writer looking for love on the internet. The teaser was recently featured by Boing Boing.

Gimme Gimme “Kure Kure Takora”

My last two posts here have been about recent deaths so here’s something lighter (?). Today a friend of mine turned me on to this crazy 1970s Japanese children’s TV show, Kure Kure Takora (commonly translated as “Gimme Gimme Octopus”). The main character is a giant red anthropomorphic octopus who covets everything he sees (and who might be based on minstrel show imagery? I can’t quite tell). He’s in love with a pink walrus and his best friend is an oversized gourd that periodically vomits coins. Other characters include a vinegar-spraying jellyfish, a cigar-smoking badger, a lazy iguana, and a trio of singing sea cucumbers. Wackiness, obviously, ensues. According to the Wikipedia there are 260 episodes, each one exactly 2 minutes and 41 seconds long.

You can watch one of them here and another one here. A DVD collection is also available for purchase or theft. And presumably it won’t be long before someone sets one of the episodes to a certain song by the Ramones.

Enjoy / forget for a while we’re all gonna die.

Tunnel vision

Hairband videos of the late-’80s seemed meta in how they “set up” the song by showing the band, usually conceitedly, approach the stage during the opening riff or drum beat, to kind of glorify, or prolong, the imminent explosion of the song (rap songs, similarly, often begin with vignettes of rappers speaking into the mic about how they are about to start rapping). Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer” (1986), whose titular contraction of “living” serves the lingo of our times, was in many ways the ultimate rock anthem video, with its talkbox riff, rigged flying theatrics, and artsy black & white lavender tint. I would “air band” it (an intricately spliced combination of air-guitar, -drums, -bass, and -vocals), running into furniture, discovering bruises the next day which unfairly implicated my parents. The song tells the story of Tommy and Gina, a young working-class couple whose love for each other compensates for their stout lives — while real life Ginas preferred displaying their mammalian buoyancies at the composer of the song, whose slo-mo moments right before the nipple highlighted videos of this nature. Of milk’s offering, newly satiated from Korova bar, we come across dystopian bros entering a tunnel in which they are to beat a homeless man to death. Anthony Burgess’s prophecy can now be seen on homeless beating videos, snuff meets Punk’d, in which teenage boys competitively break faces with cinder blocks and bats, the retina display of life perhaps more convincing than a video game. Misandry just happens. One may wonder if all videos are essentially games, life’s diorama inside a cartridge, the control pad’s rubber buttons as numb nipples whose virtual and distant volition is an actual child, silhouetted with his co-conspirators, in infamous anonymity.

Why Frances Ha Is a Cowardly Movie

Instead of attending an opening for a collective of internet/new media artists in Red Hook, probably cutting edge, funny, with free alcohol—perhaps some level of thought-provoking, also maybe I would’ve known some people there—I decided to go see Francis Ha. Something said it was like Baumbach meets Girls, and since Lena Dunham and the aforementioned filmmaker (whose notoriety is mainly based on a 2005 family drama and his friendship with the more marketable and visually stylistic Wes Anderson) both, in the shallow arc of their careers, mark an acme of New York indie-cum-commercial, I figured I’d get more pleasure and cultural experience out of going to the movies. I’ve always been attracted to the medium’s commercial roots: the amount of money it takes for a 90-minute feature to be made: the amount of money it costs to finance advertising: the amount it costs to see it once in theaters. Counteracted against the mutable possibilities for distribution and audience now made possible by the internet. It’s a weird time to consider one’s self an artist making movies, probably. Weirder than posting photos of a MacBook in a bathtub to a Tumblr.

Even weirder to film your movie in black and white. A bold choice, it actually succeeds, raw and captivating rather than kitschy and meaningless. Baumbach creates a Manhattan-like air to parts of the city heretofore unexplored in traditional analogue (i.e., Brooklyn). Its passé, but really more pastiche, approach to the cinematography feels enhanced by the literal quality of the film print. I don’t really know how that works, but certain moments feel faster, like World War II footage or old home movies. Frances (Greta Gerwig) runs down the crosswalks of lower Manhattan to “Modern Love” dancing and sort of fluttering. It’s not dramatic; it’s comic and natural and sort of frantic.

And that’s how the majority of the film is. People in their mid-20s banter and talk around ideas (and the dialogue is good, not parodic, not pandering or striving to capture some extant zenith of hipster inflection). Everyone wants to be an artist, but nobody really cares or knows how. Frances, an aspiring modern dancer and graduate of Vassar, traverses six shared, and unsuitable, residences, not including a 48-hour stint at a friend of an acquaintance’s apartment in Paris, over the course of maybe eighteen months. She fails at relationships, she sulks and hopes and talks like an intelligent person who doesn’t care about being intelligent. Someone at a dinner party says something like, “Sophie—she’s really smart,” to which Frances replies something like, “Well, yeah, we’re all smart.” She claims her friend doesn’t read enough, but we only see the protagonist flipping through the center of some thick book, ostensibly Proust, on one of her countless wasted days.

Frances is wildly unmotivated and expects a natural progression of success in the art world from minimal, obligatory efforts. She has basal talent, illusory goals and lots of beer. And she gets drunk a lot, fractiously speaking down paths of unrelatable and undetectable revelation amongst people either too mature for her company or just as immature and wanton, but rich. Frances isn’t rich. By economic and social terms, she is absolutely poor, but addressing the harrowing nature and implications of this situation becomes increasingly difficult, as she admits, when confronted by her vague love interest and roommate, that she cannot be poor, essentially because she is educated, art-minded and white. The story really does seem beautiful. It is more honest and intense than Girls, more willing to quietly face the complications of inheriting a broken economy, a feeling and system of entitlement, privilege and unwarranted desire. Nothing could really be more current, topical, desperately vital to address.

Oh god, I’m so sad. Frances Ha comes so close.

Animated Gifs as Cinema

I was planning to put up the next installment in my experimental fiction series today (part 1, part 2), but school has interfered. (I’m writing a paper on Dickens’s use of the narrative present in Great Expectations, plus grading 40-something research papers written in response to Hanna Rosin’s The End of Men: And the Rise of Women.)

In the off chance that you’d like to read something new by me, I recently published an article at the film site Press Play, “Are Animated Gifs a Type of Cinema?” Since then, Landon Palmer has responded with an article at Film School Rejects (“Animated Gifs are Cinematic, But They’re Much More Than Cinema“), as has Wm. Ferguson at the 6th Floor, the New York Times Magazine‘s blog (“On the Aesthetics of the Animated GIF“). I’m planning a follow-up post as well as an interview with Eric Fleischauer and Jason Lazarus, the directors of the gif anthology film twohundredfiftysixcolors, whose premiere I managed to catch a few weeks back. And the Press Play article is itself a follow-up to two articles I posted at Big Other in early 2011: “How Many Cinemas Are There?” and “Why Do You Need So Many Cinemas?”

I’m only just beginning my studies on the gif, so I appreciate any and all feedback.

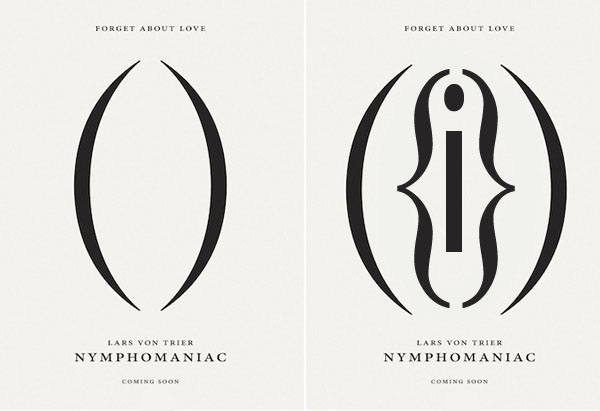

Nymphomaniac

As we await Lars Von Trier’s Nymphomaniac, which seems like a sexual extension of Charlotte Gainsbourg’s character in Antichrist (2009), we are given — in the teaser poster — suggestive syntactical vulva by way of parentheses, which may bring to mind Seymour’s “bouquet of very early-blooming parentheses” in J.D. Salinger’s Seymour: An Introduction (1959). The impulse to render images using syntax turns <3 into a ♥, distilling language back into the Lascaux cave drawings, cuneiform, hieroglyphics, and early Chinese characters. Perhaps we want to move backwards, scratching images into dirt. A more meta interpretation of () might be the excised (implied) parenthetical note, though that is unlikely. This contributor, whose brief up-close encounters with female genitalia have been mostly with eyes closed, offers a more explicit rendering — the “i” perhaps hopeful first person, as in the first person to third base. If there is a douche in this enterprise, please apply your gaze at Lars himself, who seems obsessed with destroying the women in his films. Martyr is just a fancy way of saying mommy. His films are slow and gorgeous, into whose pretentiousness one simply caves. A common still shows Gainsbourg sandwiched between two black men as Oreo coitus. Shia LaBeouf’s in it, and you get to see his dong. The spectacle just wants eyes, not approval. I’ll see you in line.