You Private Person: An Interview with Richard Chiem

I interviewed Richard Chiem on the occasion of his first book, You Private Person, published by Scrambler Books. Photos via Frances Dinger and (the above) Matthew Simmons.

What was your favorite book when you were younger? What books have made you lol or cry or feel excited?

I think I read a lot of Goosebumps books and Animorphs books, and I was trying to collect the whole series for each. If I think about 1995, there were many times of me just waiting by myself inside a Safeway, because you could find them in the book aisle. I could read one of those books in about two and a half hours, so it became an easy addiction, since I wanted to know everything, to know the whole story. I would stack up my stacks of books next to my video games and my comic books in towers. They were each numbered like episodes, and in different colors. It seemed perfect to me at the time to have them all. I would save up six or seven dollars, everything other week or so in 1995, waiting in line at a Safeway. I recognized a particular need to read. But they never made me cry or laugh. I don’t really remember what exactly I was feeling when I was eight years old, in third grade, but I remember those simple horror and adventure stories, and I can still talk about them.

I turn on subtitles when I watch movies now. Some of my friends hate it and some really like it. It was adding another dimension to every movie and it quickened the pace of the viewing experience for me. And I watch a lot of movies. I always write after watching

a movie when everything still feels really alive about the story.

In defense of romance novels

Piggybacking on Mike’s earlier post, I have long found it curious that the romance novel is the one genre no one wants to defend. (See, for instance, this comment.) But time was, romance was the genre.

Piggybacking on Mike’s earlier post, I have long found it curious that the romance novel is the one genre no one wants to defend. (See, for instance, this comment.) But time was, romance was the genre.

It seems to me that the contemporary romance novel—of the paperback bodice ripper variety (see right)—arrived on our shores of our literary imagination in no small part due to writers like D. H. Lawrence. And what could be more literary than Lawrence? I myself can conceive of no formal reason why a romance novel can’t be art. Indeed, I suspect that someone out there is already writing great ones. (Hell, isn’t Lolita a romance novel?)

Part of what I love about this Chicago Reader review of The Twilight Saga: Eclipse is its understanding of how Stephanie Meyers’s books and the resulting films—regardless of their quality (I haven’t read or seen them yet, though I intend to)—do partake of a larger literary tradition:

On the inevitability of more Star Wars films

| film | year | production budget | worldwide gross |

| Star Wars | 1977 | $11 million | $775,398,007 |

| The Empire Strikes Back | 1980 | $18 million | $538,375,067 |

| Return of the Jedi | 1983 | $32.5 million | $475,106,177 |

| The Phantom Menace | 1999 | $115 million | $1,027,044,677 |

| Attack of the Clones | 2002 | $115 million | $649,398,328 |

| Revenge of the Sith | 2005 | #113 million | $848,754,768 |

| $404.5 million | $4,314,077,024 |

Net profit: 3.9 billion dollars.

And that’s just ticket sales.

Stanley Kubrick’s first feature film, “Fear and Desire” (1953), comes out today on Blu-Ray

What the title says. This is the first time Fear and Desire has been available on DVD.

The film was written by Howard Sackler, who later won the Tony and Pulitzer (in 1969) for his play The Great White Hope. And it stars Paul Mazursky, whom of course we all know from inventing hipster culture.

I saw it once on VHS (a terrible bootlegged copy) back in the late 1990s. I’ll be curious to revisit it. What I remember most of all is the strength of Kubrick’s cinematography (unsurprising, given his background as a photographer).

(It should be noted that Kubrick disowned the film, going so far as to block its release during his lifetime.)

Holy shit, Kōji Wakamatsu died

He got hit by a taxi three days ago. Cripes.

Wakamatsu started directing in the early 1960s, primarily making highly artistic and complex exploitation films. His 1969 feature Go, Go Second Time Virgin has long been a favorite of mine:

The Boys from Oz

Australians have a history of distrust with the suburban space. It’s one that I think is far more ingrained than the ongoing American preoccupation with the suburbs. The abjection, otherness, decay and concealed violence of the suburban space, and the affect this space has on the Australian male, is an important part of the Australian imaginary. This is evident with the continuous repetition of these themes, particularly criminality and violence, in a whole host of recent films: Wish You Were Here (2012), Snowtown (2011), Animal Kingdom (2010), Somersault (2004), The Boys (1998) and Head On (1998).

I’ve chosen to talk about The Boys and Animal Kingdom because I think that they offer a distinct and unique portrayal of masculinity: one that is on the borderline, in between the public and private, criminality and legality, contained in an uncanny domestic space. The everyday suburban space is ruptured, undone and exposed as an unsettling site for a stifling and childlike male development, categorised by violence and the need to return to the maternal. This is the common trope in Australian domestic cinema ‘which finds expression in a distorted reflection akin to a hall of mirrors; each person staring back is undoubtedly familiar, but is in some way simultaneously emphasised, concealed and misshapen.’ (Thomas and Gillard, Metro Magazine, 2003)

September 27th, 2012 / 11:19 pm

Mickey Mouse Sweaters

Choosing clothes can be very vexing. Sometimes I think that the turmoil of buying clothes is similar to the kind that exists in the Middle East. There’s screaming, destruction, and lots of second-guessing.

My most recent fashion crisis involves not a weird YouTube video but a Mickey Mouse sweater. I first saw the Mickey Mouse sweater at a vintage store in the East Village. When I noticed that marvelous boy mouse on the faded blue garment I became awfully excited.

Fear, Loathing, and Comics

Comic book artist, Ed Piskor

If you’re walking the streets of Pittsburgh at night, be prepared to encounter an intimidating gang of comic book artists. There’s Ed Piskor, who wears sunglasses indoors, has a different Public Enemy t-shirt for every day of the week, and who Rolling Stone calls “the next big thing in books”. There’s Tom Scioli, who stutters a tad with delight when retrieving a comics-related file from his encyclopedic mind, and whose work on Godland and American Barbarian is compared to that of the eminent, Jack Kirby. Then there’s indie artist, Jim Rugg, whose books Street Angel and the Eisner-nominated Afrodisiac have made big waves in the small press scene. He also co-hosts a podcast called Tell Me Something I Don’t Know with artist, Jasen Lex. BFFs since college, they grill folks, such as Hellboy’s Mike Mignola, on what it means to live and work as an artist.

If these guys are excited about something, so am I. So when they invited me to film them at a “special event”, I jumped at the opportunity. Then they told me the shoot would take place in a subterranean warehouse in the middle of nowhere.

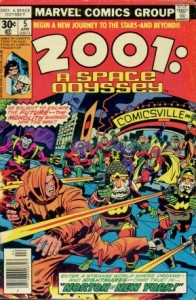

Jack Kirby’s 2001 series, in the basement

“No, you see, this basement is legendary,” they said.

Painkiller post

When a man with a torn spleen and two broken ribs takes three days off from work, Netflix instant, Oxycodone, and his ability to shit again quickly turns into the center of his universe. When he is reduced by lack of selection to watching a romantic comedy whose target audience are creative menopausal upper-middle class spinsters, you know a blog post is brewing. Something’s Gotta Give (2003) is about Erica Barry (Diane Keaton), a successful playwright who, in the afterglow of coitus with Harry Sanborn (Jack Nicholson), tearfully says she had considered her body “closed for business,” a sentiment even this 36-year-old male can relate to. Oxycodone softens the edges around this world, the frayed bones directed at my lungs, the hazy glow of a movie I have no business watching, on my couch, grimacing in pain with every biochemically induced, or at least mediated, laugh. I may be high. It’s probably the drug, but slowly along the way the movie started to scare me. Perhaps it was the Kubrickian camera slowly going over each square inch of their Hampton summer house — the long contemplative and eery takes which seemed to impart meaning simply by existing in real time with the matter it was recording, as if our director Nancy Myers had just enough faith that this world was innately fucked up enough to scare the living shit (figuratively; your contributor is constipated) out of someone. Much has been written about the symbolism and space of The Shining (1980), whose quotidian grotesqueness is almost invisible, thus horrifying. To finally look yourself honestly in a mirror is to see murder.